1983 Conversation with Haidy Schreker-Bures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Catalogue 2006 Catalogue Complete

COMPLETE CATALOGUE 2006 COMPLETE CATALOGUE Inhalt ORFEO A – Z............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Recital............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................82 Anthologie ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................89 Weihnachten ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................96 ORFEO D’OR Bayerische Staatsoper Live ...................................................................................................................................................................................................99 Bayreuther Festspiele Live ...................................................................................................................................................................................................109 -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site: Recording: March 22, 2012, Philharmonie in Berlin, Germany

21802.booklet.16.aas 5/23/18 1:44 PM Page 2 CHRISTIAN WOLFF station Südwestfunk for Donaueschinger Musiktage 1998, and first performed on October 16, 1998 by the SWF Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Jürg Wyttenbach, 2 Orchestra Pieces with Robyn Schulkowsky as solo percussionist. mong the many developments that have transformed the Western Wolff had the idea that the second part could have the character of a sort classical orchestra over the last 100 years or so, two major of percussion concerto for Schulkowsky, a longstanding colleague and friend with tendencies may be identified: whom he had already worked closely, and in whose musicality, breadth of interests, experience, and virtuosity he has found great inspiration. He saw the introduction of 1—the expansion of the orchestra to include a wide range of a solo percussion part as a fitting way of paying tribute to the memory of David instruments and sound sources from outside and beyond the Tudor, whose pre-eminent pianistic skill, inventiveness, and creativity had exercised A19th-century classical tradition, in particular the greatly extended use of pitched such a crucial influence on the development of many of his earlier compositions. and unpitched percussion. The first part of John, David, as Wolff describes it, was composed by 2—the discovery and invention of new groupings and relationships within the combining and juxtaposing a number of “songs,” each of which is made up of a orchestra, through the reordering, realignment, and spatial distribution of its specified number of sounds: originally between 1 and 80 (with reference to traditional instrumental resources. -

CHINEKE! ORCHESTRA Kevin John Edusei Conductor

SIGCD517_Bklt****.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 28/04/2017 16:19 Page 1 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CyAN mAGENTA Customer yEllOw Catalogue No. BlACK Job Title page Nos. Antonin Dvořák SympHONy NO.9, ‘FROm THE NEw wORlD’ Jean Sibelius FINlANDIA CHINEKE! ORCHESTRA Kevin John Edusei conductor 16 1 291.0mm x 169.5mm SIGCD517_Bklt****.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 28/04/2017 16:19 Page 2 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CyAN mAGENTA Customer yEllOw Catalogue No. BlACK Job Title page Nos. Jean Sibelius Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) Finlandia Finlandia, Op 26 9’ Antonin Dvořák A brief trip to Finland is all that is required to grasp the legendary status that Jean Sibelius has acquired in his home nation. From his long-time home, Ainola, which has become a national Symphony No. 9, ‘From the New world’ museum, it is a mere 30 minute drive to Sibelius park in Helsinki, where sits the Sibelius monument. Budding Finnish musicians attend the Sibelius Academy, partake in the International Jean Sibelius Violin Competition and perform his symphonies in Sibelius Hall. Until the introduction of the euro, his portrait was on the Finnish 100 mark bill and Finland’s 1. Finlandia Jean Sibelius .....................................................................................................................................................[7.50] national Flag Day is now held on his birthday. But how did a musician and composer become a national hero, a position usually reserved for generals, freedom fighters and politicians? Symphony No. 9 in E Minor, Op. 95, ‘From the New World’ Antonin Dvořák 2. I. Adagio - Allegro molto ...............................................................................................................................................[11.42] e answer lies with Finlandia, Sibelius’ love letter to the Finnish nation. -

Bernard Coutaz Carlos Sandúa Las Músicas Del Agua La ONE Republicana Natalie Dessay Peter Donohoe Lado Ataneli Gaspard De La N

REVISTA DE MÚSICA Año XXIII - Nº 228 - Marzo 2008 - 6,50 € DOSIER Las músicas del agua ENCUENTROS ROLA Bernard Coutaz ND Carlos Sandúa C O ACTUALIDAD R V E IL Natalie Dessay A L N A Peter Donohoe D ZÓN Lado Ataneli O EM REPORTAJE OCIONES La ONE republicana Año XXIII - Nº 228 Marzo 2008 REFERENCIAS Gaspard de la nuit de Ravel INTERIORPORTADA FILM:SCHERZO 22/2/08 18:37 Página 1 1-16 FILM:SCHERZO 22/2/08 17:36 Página 1 AÑO XXIII - Nº 228 - Marzo 2008 - 6,50 € 2 OPINIÓN DOSIER Las músicas del agua CON NOMBRE José Luis Carles PROPIO y Cristina Palmese 113 6 Natalie Dessay Rafael Banús Irusta ENCUENTROS 8 Peter Donohoe Bernard Coutaz Bruno Serrou Emili Blasco 126 10 Lado Ataneli Carlos Sandúa Pablo J. Vayón Barbara Röder 132 12 AGENDA REPORTAJE La Orquesta Nacional 18 ACTUALIDAD Republicana NACIONAL Enrique Lacomba y Gúzman Urrero Peña 136 46 ACTUALIDAD INTERNACIONAL EDUCACIÓN Pedro Sarmiento 140 60 ENTREVISTA JAZZ Rolando Villazón Pablo Sanz 142 Juan Antonio Llorente LIBROS 144 64 Discos del mes LA GUÍA 146 65 SCHERZO DISCOS CONTRAPUNTO Norman Lebrecht 152 Sumario Colaboran en este número: Javier Alfaya, Julio Andrade Malde, Íñigo Arbiza, Emili Blasco, Alfredo Brotons Muñoz, José Antonio Cantón, José Luis Carles, Jacobo Cortines, Rafael Díaz Gómez, Pierre Élie Mamou, José Luis Fernández, Fernando Fraga, Germán Gan Quesada, Joaquín García, José Antonio García y García, Carmen Dolores García González, Juan García-Rico, José Guerrero Martín, Federico Hernández, Fernando Herrero, Bernd Hoppe, Paul Korenhof, Enrique Lacomba, Antonio Lasierra, Norman -

I Urban Opera: Navigating Modernity Through the Oeuvre of Strauss And

Urban Opera: Navigating Modernity through the Oeuvre of Strauss and Hofmannsthal by Solveig M. Heinz A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Germanic Languages and Literatures) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Vanessa H. Agnew, Chair Associate Professor Naomi A. André Associate Professor Andreas Gailus Professor Julia C. Hell i For John ii Acknowledgements Writing this dissertation was an intensive journey. Many people have helped along the way. Vanessa Agnew was the most wonderful Doktormutter a graduate student could have. Her kindness, wit, and support were matched only by her knowledge, resourcefulness, and incisive critique. She took my work seriously, carefully reading and weighing everything I wrote. It was because of this that I knew my work and ideas were in good hands. Thank you Vannessa, for taking me on as a doctoral rookie, for our countless conversations, your smile during Skype sessions, coffee in Berlin, dinners in Ann Arbor, and the encouragement to make choices that felt right. Many thanks to my committee members, Naomi André, Andreas Gailus, and Julia Hell, who supported the decision to work with the challenging field of opera and gave me the necessary tools to succeed. Their open doors, email accounts, good mood, and guiding feedback made this process a joy. Mostly, I thank them for their faith that I would continue to work and explore as I wrote remotely. Not on my committee, but just as important was Hartmut. So many students have written countless praises of this man. I can only concur, he is simply the best. -

Eberhard Kloke · Wieviel Programm Braucht Musik? Eberhard Kloke (* 1948 in Hamburg)

Eberhard Kloke · Wieviel Programm braucht Musik? Eberhard Kloke (* 1948 in Hamburg). Nach Kapellmeistertätigkeiten in Mainz, Darmstadt, Düsseldorf und Lübeck wurde Eberhard Kloke 1980 als Generalmusikdirektor nach Ulm berufen und ging 1983 in gleicher Position nach Freiburg im Breisgau. 1988 bis 1994 war er Generalmusikdirektor der Bochumer Symphoniker, und von 1993 bis 1998 übernahm er die Leitung der Nürnberger Oper und des Philharmonischen Orchesters Nürnberg. 1990 wurde Kloke mit dem Deutschen Kritikerpreis ausgezeichnet. Die Musik der Moderne bildet das Zentrum der künstlerischen Arbeit von Eberhard Kloke. In Freiburg, Bochum und Nürn- berg und von Berlin aus organisierte und leitete er großangelegte Zyklen mit zeitgenös- sischer Musik-Programmatik (Götterdämmerung_Maßstab und Gemessenes; Jakobsleiter, Ein deutscher Traum, Aufbrechen Amerika, Prometheus, Jenseits des Klanges). Seit 1998 lebt er als freiberuflicher Dirigent und Projektemacher in Berlin und gründete im Hinblick auf seine vielfältigen kulturellen Aktivitäten den Verein musikakzente 21. Seit 2001 erwei- terte sich das Arbeitsspektrum um kuratorische Aufgaben und kompositorische Heraus- forderungen. Wieviel Programm braucht Musik? Programm Musik-Konzept: Eine Zwischenbilanz 1980– 2010 Eberhard Kloke ISBN 978-3-89727-447-1 © 2010 by PFAU-Verlag, Saarbrücken Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Umschlaggestaltung: Sigrid Konrad, Saarbrücken Layout und Satz: Judy Hohl, Alexander Zuber Lektorat: Heinz-Klaus Metzger, Rainer Riehn Printed in Germany PFAU-Verlag · Hafenstr. 33 · D 66111 Saarbrücken www.pfau-verlag.de · www.pfau-music.com · [email protected] Wieviel Programm braucht Musik? Programm Musik-Konzept: Eine Zwischenbilanz 1980– 2010 4 Leitfaden für das Handbuch 8 Kapitel 1 Die Krise des Programmatischen Musik und ihr Programm in den öffentlichen Erscheinungsformen 14 Kapitel 2 Von der Expansion der Klangdistrikte Programm als musikalisches Konzept Übersicht zu den Kapiteln 3, 4 und 5: S. -

JUNE 2014 LIST See Inside for Valid Dates

tel 0115 982 7500 fax 0115 982 7020 JUNE 2014 LIST See inside for valid dates Dear Customer, 11th June sees the 150th anniversary of the birth of Richard Strauss and we have already seen a good sprinkling of new releases and re-issues appear in celebration this year. Thielemann’s new Elektra for DG is probably the highest-profile release this month, featuring a magnificent cast that includes Rene Pape and Anne Schwanewilms. Sadly, we hadn’t yet managed to obtain a preview copy at the time of going to print, but it certainly looks very promising! DG are also issuing a deluxe LP-sized boxset of Karajan’s analogue Strauss recordings this month that will feature 11 CDs, plus the entire contents on a single Blu-ray Audio. As is the trend at the moment, it will be a limited edition set packed full of extra material including photos and original liner notes. See p.2 for more information. Continuing with the Strauss theme, you may also like to take a look at the listing we have compiled of recordings from various independent labels. This covers 3½ pages (pp.10-13) and features some truly great titles. A good opportunity to fill in gaps in the library! Away from Strauss, other things to point out are a further batch of Most Wanted Recitals from Decca, featuring wonderful discs from the likes of Siepi, Nilsson, Souzay, Carreras etc. Harmonia Mundi are issuing another 10 titles in their HM Gold series - top recordings moved from their full-price catalogue down to mid-price. -

The 2017/18 Season: 70 Years of the Komische Oper Berlin – 70 Years Of

Press release | 30/3/2017 | acr | Updated: July 2017 The 2017/18 Season: 70 Years of the Komische Oper Berlin – 70 Years of the Future of Opera 10 premieres for this major birthday, two of which are reencounters with titles of legendary Felsenstein productions, two are world premieres and four are operatic milestones of the 20 th century. 70 years ago, Walter Felsenstein founded the Komische Oper as a place where musical theatre makers were not content to rest on the laurels of opera’s rich traditions, but continually questioned it in terms of its relevance and sustainability. In our 2017/18 anniversary season, together with their team, our Intendant and Chefregisseur Barrie Kosky and the Managing Director Susanne Moser are putting this aim into practice once again by way of a diverse program – with special highlights to celebrate our 70 th birthday. From Baroque opera to operettas and musicals, the musical milestones of 20 th century operatic works, right through to new premieres of operas for children, with works by Georg Friedrich Handel through to Philip Glass, from Jacques Offenbach to Jerry Bock, from Claude Debussy to Dmitri Shostakovich, staged both by some of the most distinguished directors of our time as well as directorial newcomers. New Productions Our 70 th birthday will be celebrated not just with a huge birthday cake on 3 December, but also with two anniversary productions. Two works which enjoyed great success as legendary Felsenstein productions are returning in new productions. Barrie Kosky is staging Jerry Brock’s musical Fiddler on the Roof , with Max Hopp/Markus John and Dagmar Manzel in the lead roles, and the magician of the theatre, Stefan Herheim, will present Jacques Offenbach’s operetta Barbe- bleue in a new, German and French version. -

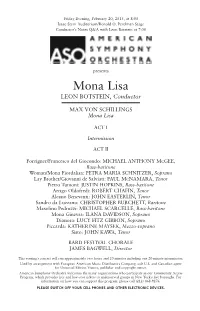

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father. -

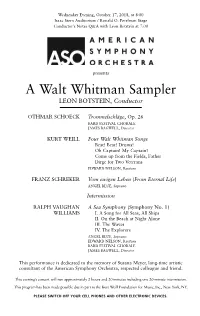

A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Wednesday Evening, October 17, 2018, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium / Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor OTHMAR SCHOECK Trommelschläge, Op. 26 BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director KURT WEILL Four Walt Whitman Songs Beat! Beat! Drums! Oh Captain! My Captain! Come up from the Fields, Father Dirge for Two Veterans EDWARD NELSON, Baritone FRANZ SCHREKER Vom ewigen Leben (From Eternal Life) ANGEL BLUE, Soprano Intermission RALPH VAUGHAN A Sea Symphony (Symphony No. 1) WILLIAMS I. A Song for All Seas, All Ships II. On the Beach at Night Alone III. The Waves IV. The Explorers ANGEL BLUE, Soprano EDWARD NELSON, Baritone BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This performance is dedicated to the memory of Susana Meyer, long-time artistic consultant of the American Symphony Orchestra, respected colleague and friend. This evening’s concert will run approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. This program has been made possible due in part to the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc., New York, NY. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director Whitman and Democracy comprehend the English of Shakespeare by Leon Botstein or even Jane Austen without some reflection. (Indeed, even the space Among the most arguably difficult of between one generation and the next literary enterprises is the art of transla- can be daunting.) But this is because tion. Vladimir Nabokov was obsessed language is a living thing. There is a about the matter; his complicated and decided family resemblance over time controversial views on the processes of within a language, but the differences transferring the sensibilities evoked by in usage and meaning and in rhetoric one language to another have them- and significance are always developing. -

Gösta Neuwirth (*1937)

© Lothar Knessl GÖSTA NEUWIRTH (*1937) Streichquartett 1976 1 Satz I 3:13 2 Satz II 4:36 3 Satz III 4:56 4 Satz IV 4:19 Sieben Stücke für Streichquartett (2008) für Ernst Steinkellner 5 d’accord 1:15 6 pensif 1:22 7 le fils de la fadeur 1:15 8 à trois 1:31 9 objet en ombre 1:06 1 0 un rêve solutréen 0:55 11 l’oubli bouilli 1:28 1 2 L’oubli bouilli (2008) 30:29 TT: 56:25 1 - 4 Annette Bik violin • Gunde Jäch-Micko violin, viola Dimitrios Polisoidis viola • Andreas Lindenbaum violoncello 5 - 11 Sophie Schafleitner violin • Gunde Jäch-Micko violin Dimitrios Polisoidis viola • Andreas Lindenbaum violoncello 5 - 12 Donatienne Michel-Dansac voice Klangforum Wien • Etienne Siebens conductor 5 - 12 Erste Bank Kompositionsauftrag 2 Klangforum Wien Klangforum Wien Vera Fischer Flöte Markus Deuter Oboe Bernhard Zachhuber, Olivier Vivarès Klarinette Gerald Preinfalk Saxophon Edurne Santos Fagott Christoph Walder Horn Anders Nyqvist Trompete Andreas Eberle Posaune Annette Bik, Sophie Schafleitner Violine Dimitrios Polisoidis, Andrew Jezek Viola Benedikt Leitner, Andreas Lindenbaum Violoncello Alexandra Dienz Kontrabass Nathalie Cornevin Harfe Krassimir Sterev Akkordeon Florian Müller Klavier, Keyboards Hsin-Huei Huang Klavier Adam Weisman, Berndt Thurner Schlagwerk Peter Böhm, Florian Bogner Klangregie und Spatialisation 3 Gösta Neuwirths Kopfwelten fehlenden Teile eins und drei lieferte. Lothar Knessl Bildlos sachliche Auskünfte zum Werk bleiben außerhalb der Schublade des Einführungszwan- L’oubli bouilli - Vanish… Ein Titel, der die Frage ges. TEIL I also, zehn Minuten: Primär linear dis- aufwirft: Wohin führen „gekochtes Vergessen und poniertes Gebilde, überwiegend dicht gewebt, Verschwinden“? Sollte sich Vergessen prozessual hie und da solistisch.