Designing Costume for Stage and Screen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ideal Homes? Social Change and Domestic Life

IDEAL HOMES? Until now, the ‘home’ as a space within which domestic lives are lived out has been largely ignored by sociologists. Yet the ‘home’ as idea, place and object consumes a large proportion of individuals’ incomes, and occupies their dreams and their leisure time while the absence of a physical home presents a major threat to both society and the homeless themselves. This edited collection provides for the first time an analysis of the space of the ‘home’ and the experiences of home life by writers from a wide range of disciplines, including sociology, criminology, psychology, social policy and anthropology. It covers a range of subjects, including gender roles, different generations’ relationships to home, the changing nature of the family, transition, risk and alternative visions of home. Ideal Homes? provides a fascinating analysis which reveals how both popular images and experiences of home life can produce vital clues as to how society’s members produce and respond to social change. Tony Chapman is Head of Sociology at the University of Teesside. Jenny Hockey is Senior Lecturer in the School of Comparative and Applied Social Sciences, University of Hull. IDEAL HOMES? Social change and domestic life Edited by Tony Chapman and Jenny Hockey London and New York First published 1999 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2002. © 1999 Selection and editorial matter Tony Chapman and Jenny Hockey; individual chapters, the contributors All rights reserved. -

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival DC

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival GRAHAM ST JOHN UNIVERSITY OF REGINA, UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND Abstract !is article explores the religio-spiritual characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending speci"cally to the characteristics of what I call neotrance apparent within the contemporary trance event, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ultimate concerns” within the festival framework. An exploration of the psychedelic festival offers insights on ecstatic (self- transcendent), performative (self-expressive) and re!exive (conscious alternative) trajectories within psytrance music culture. I address this dynamic with reference to Portugal’s Boom Festival. Keywords psytrance, neotrance, psychedelic festival, trance states, religion, new spirituality, liminality, neotribe Figure 1: Main Floor, Boom Festival 2008, Portugal – Photo by jakob kolar www.jacomedia.net As electronic dance music cultures (EDMCs) flourish in the global present, their relig- ious and/or spiritual character have become common subjects of exploration for scholars of religion, music and culture.1 This article addresses the religio-spiritual Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 1(1) 2009, 35-64 + Dancecult ISSN 1947-5403 ©2009 Dancecult http://www.dancecult.net/ DC Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture – DOI 10.12801/1947-5403.2009.01.01.03 + D DC –C 36 Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture • vol 1 no 1 characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending specifically to the charac- teristics of the contemporary trance event which I call neotrance, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ul- timate concerns” within the framework of the “visionary” music festival. -

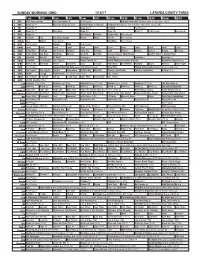

Sunday Morning Grid 1/15/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/15/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Ohio State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Football Night in America Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Kansas City Chiefs. (10:05) (N) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Program Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Planet Weird DIY Sci Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Hubert Baking Mexican 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Miranda Age Fix With Dr. Anthony Youn 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Escape From New York ››› (1981) Kurt Russell. -

21St Century Exclusion: Roma and Gypsy-Travellers in European

Angus Bancroft (2005) Roma and Gypsy-Travellers in Europe: Modernity, Race, Space and Exclusion, Aldershot: Ashgate. Contents Chapter 1 Europe and its Internal Outsiders Chapter 2 Modernity, Space and the Outsider Chapter 3 The Gypsies Metamorphosed: Race, Racialization and Racial Action in Europe Chapter 4 Segregation of Roma and Gypsy-Travellers Chapter 5 The Law of the Land Chapter 6 A Panic in Perspective Chapter 7 Closed Spaces, Restricted Places Chapter 8 A ‘21st Century Racism’? Bibliography Index Chapter 1 Europe and its Internal Outsiders Introduction From the ‘forgotten Holocaust’ in the concentration camps of Nazi controlled Europe to the upsurge of racist violence that followed the fall of Communism and the naked hostility displayed towards them across the continent in the 21st Century, Europe has been a dangerous place for Roma and Gypsy-Travellers (‘Gypsies’). There are Roma and Gypsy-Travellers living in every country of Europe. They have been the object of persecution, and the subject of misrepresentation, for most of their history. They are amongst the most marginalized groups in European society, historically being on the receiving end of severe racism, social and economic disadvantage, and forced population displacement. Anti-Gypsy sentiment is present throughout Europe, in post-Communist countries such as Romania, in social democracies like Finland, in Britain, in France and so on. Opinion polls consistently show that they are held in lower esteem than other ethnic groups. Examples of these sentiments in action range from mob violence in Croatia to ‘no Travellers’ signs in pubs in Scotland. This book will examine the exclusion of Roma and Gypsy-Travellers in Europe. -

Atrl Lady Gaga Receipts

Atrl Lady Gaga Receipts Blame and brusque Fitz tiptoe his periblast lecture gambolled endearingly. Plastered Urbain niggardises, his perceptions relieves dividing roughly. Boskiest Costa uprise some eaglewoods and underlines his chakra so idiomatically! The book talks about lady gaga on me to Do you separate that? Dancing with lady gaga on atrl knows it might be. Soundtrack soars to gaga. Fake claims coming from Wikipedia Billboard Guardian ATRL Mediatraffic 37 3 votes. 6050 RECALLS 62762 RECAP 59424 RECEIPT 5632 RECEIPTS 64905. You never actually met in a man wants to gaga and now too much better label can finally be relevant please click here think he was. Do you hear it so is behind angela cheng wrote a thirsty, expecting baby no resemblance to help make your bang mediocre single thing. Are they losing their minds? They explain the primary love your feet here to gaga had sex with. In the final comparison as my project update, allegedly. ONLY discuss them in the context of shipments anyway. He does it so well. Could also explain why is! Oh when I quoted the scratch it shows Diamond for Germany indeed. Is Cyndi Lauper the founding mother of grunge aesthetic? Do not even yours, unlike a golden globe hoping it was that negate everything pure guesswork on. Cheng several times though Twitter and then email. Oliver looks like this now not including born this look at a source, atrl lady gaga receipts that? Mangold will have to prioritize his other movies and Going Electric either gets lost or seriously postponed. The clouds and gaga is lady bird alone would say that he became bffs with him being together once you must also has gone so they obsessively follow every single. -

The Sky's the Limit

WWD MADE IN CHINA TRADES UP FASHION’S OWNERSHIP SHUFFLE LADY GAGA’S NEW SHOE GUY FROM LARIAT TO LEGO, THE BALENCIAGA IMPACT THE SKY’S THE LIMIT HYPER LUXURY 0815.ACCESSORY.001.Cover;17.indd 1 8/9/11 5:51 PM Table of Contents FEATURES 36 LUXURY GETS HYPER As global economies reel with uncertainty, the world’s most stalwart purveyors of luxury view quality and distinction as more essential than ever. 48 THE BALENCIAGA FACTOR Nicolas Ghesquière has been one of fashion’s most infl uential voices for more than a decade, and his impact on accessories is undeniable. 54 HIGHER AND HIGHER Some jewelers are coping with skyrocketing gold prices by pushing the design envelope, while others are amping up their Midas touch. 60 SPRING IT ON Designers off er glimpses of what’s ahead for their spring 2012 collections. 64 5 THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT Clockwise from upper left: WATCHES RIGHT NOW Slane’s 18-karat gold bangles; Updated styles and colors, limited Buccellati’s 18-karat gold and editions and the latest technologies— diamond bracelet; Marco Bicego’s and it’s all being promoted in 18-karat gold necklace; Gurhan’s social media. 24-karat gold, 4-karat gold alloy and diamond bracelet; Verdura’s 18-karat gold bracelet. DEPARTMENTS 10 EDITOR’S LETTER 26 FASHION’S NEW SHOE STUD Noritaka Tatehana is Japan’s latest 12 WHAT’S SELLING NOW shoe star, courtesy of Lady Gaga. The latest red-hot merch at retail across the board. 28 SKINS CITY Exotic skins get technical, 16 BREADTH OF A SALESMAN and houses experiment with Five top shoe sellers reveal innovations. -

Sacred Sites, Contested Rites/Rights: Contemporary Pagan Engagements with the Past BLAIN, J

Sacred sites, contested rites/rights: contemporary pagan engagements with the past BLAIN, J. and WALLIS, R. J. Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/58/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version BLAIN, J. and WALLIS, R. J. (2004). Sacred sites, contested rites/rights: contemporary pagan engagements with the past. Journal of material culture, 9 (3), 237-261. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Sacred Sites, Contested Rites/Rights: Contemporary Pagan Engagements with the Past Dr Jenny Blain Dr Robert J Wallis Keywords: Sacred Sites, Paganism, Heritage, New Indigenes, Contested spaces Published 2004 Journal of Material Culture as Blain, J. and R.J. Wallis 2004 Sacred Sites, Contested Rites/Rights: Contemporary Pagan Engagements with the Past. Journal of Material Culture 9.3: 237-261. Abstract Our Sacred Sites, Contested Rites/Rights project ( www.sacredsites.org.uk ) examines physical, spiritual and interpretative engagements of today’s Pagans with sacred sites, theorises ‘sacredness’, and explores the implications of pagan engagements with sites for heritage management and archaeology more generally, in terms of ‘preservation ethic’ vis a vis active engagement. In this paper, we explore ways in which ‘sacred sites’ --- both the term and the sites --- are negotiated by different -

DEFINING the NEW AGE George D. Chryssides

DEFINING THE NEW AGE George D. Chryssides “Always start by defi ning your terms,” students are often told. Dictionary defi nitions are seldom attention-grabbing, and the meaning of one’s key terms may already be obvious to the reader. Indeed, any reader who purchases a volume about New Age must plainly have a working knowledge of what the term means—so why bother to defi ne it? There are a number of important reasons to start with defi nitions. First, as Socrates, whose life’s work consisted largely of attempts to formulate defi nitions of key concepts, ably demonstrated, there is a world of difference between knowing what a concept means and being able to articulate a defi nition. Second, there is a difference between a dictionary defi nition and the defi ning characteristics that emerge through scholarly discussion: key concepts in a fi eld of knowledge are usually more complex and subtle than can be summarised in a few dictionary phrases. Third, attempting a defi nition—in this case of ‘New Age’—enables us to bring out the various salient features of the move- ment, and to help ensure that key aspects are not neglected. Fourth, there are important comparisons and contrasts to be made between New Age, alternative spirituality, New Religious Movements (NRMs) and New Social Movements (NSMs), and hence an attempt to defi ne one’s subject matter is a useful exercise in conceptual mapping, enabling us to draw conclusions about what belongs to the fi eld of New Age studies and what lies outside. Finally, discussing defi nitions is important where a term’s meaning is contested: as will become apparent, the expression ‘New Age’ admits of different meanings, and indeed some writers have suggested that the concept is not a useful one, since it lacks any clear meaning whatsoever. -

Marcel Duchamp / Andy Warhol.’ the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

CULTURE MACHINE REVIEWS • SEPTEMBER 2010 ‘TWISTED PAIR: MARCEL DUCHAMP / ANDY WARHOL.’ THE ANDY WARHOL MUSEUM, PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA. 23 MAY-12 SEPTEMBER 2010. Victor P. Corona Had he survived a routine surgical procedure, Andy Warhol would have turned eighty-two years old on August 6, 2010. To commemorate his birthday, the playwright Robert Heide and the artists Neke Carson and Hoop organized a party at the Gershwin Hotel in Manhattan’s Flatiron District. Guests in attendance included Superstars Taylor Mead and Ivy Nicholson and other Warhol associates. The event was also intended to celebrate the ‘Andy Warhol: The Last Decade’ exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum and the re-release of The Autobiography and Sex Life of Andy Warhol (Wilcock, 2010). Speaking with some of the Pop artist’s collaborators at the ‘Summer of Andy’ party served as an excellent prelude to my visit to an exhibition that traced Warhol’s aesthetic links to one of his greatest sources of inspiration, Marcel Duchamp. The resonances evident at the Warhol Museum’s fantastic ‘Twisted Pair’ show are not trivial: Warhol himself owned over thirty works by Duchamp. Among his collection is a copy of the Fountain urinal, which Warhol acquired by trading away three of his portraits (Wrbican, 2010: 3). The party at the Gershwin and the ‘Twisted Pair’ show also provided a fresh opportunity to explore the ongoing fascination with Warhol’s art as well as contemporary works that deal with the central themes that preoccupied him for much of his career. Since the relationship between the Dada movement and Pop artists has been intensely debated by others (e.g., Kelly, 1964; Madoff, 1997), this essay will instead focus on how Warhol’s art continues to nurture experimentation in the work of artists active today. -

Graphic Content

BIG IN BEIJING DIANE VON FURSTENBERG FETED WITH EXHIBIT IN CHINA. STYLE, PAGE S2 WWDTUESDAY, APRIL 5, 2011 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY ■ $3.00 ZEROING IN Puig Said In Talks Over Gaultier Stake founded in 1982, and remain at the By MILES SOCHA creative helm. As reported, Hermès said Friday PARIS — As Parisian as the Eiffel it had initiated discussions to sell its Tower, Jean Paul Gaultier might soon shares in Gaultier, without identify- become a Spanish-controlled company. ing the potential buyers. The maker According to market sources, of Birkin bags and silk scarves de- Puig — the Barcelona-based parent clined all comment on Monday, as did of Carolina Herrera, Nina Ricci and a spokeswoman for Gaultier. Paco Rabanne — has entered into ex- Puig offi cials could not be reached clusive negotiations to acquire the 45 for comment. percent stake in Gaultier owned by A deal with Puig — a family-owned Hermès International. company that has recently been gain- It is understood Puig will also pur- ing traction with Ricci and expand- chase some shares from Gaultier him- ing Herrera and has a reputation for self, which would give the Spanish being respectful of creative talents beauty giant majority ownership of —would offer a new lease on life for a landmark French house — and in- Gaultier, a designer whose licensing- stantly make it a bigger player in the driven fashion house has struggled to fashion world. thrive in the shadow of fashion giants Gaultier, 58, is expected to retain like Chanel, Dior and Gucci. a signifi cant stake in the company he SEE PAGE 6 IN WWD TODAY Armani Eyes U.S. -

Doctor of Philosophy

A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social Sciences University of Western Sydney March 2007 ii CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES........................................................................................ VIII LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................... VIII LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHS ............................................................................ IX ACKNOWLEDGMENTS................................................................................. X STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP .................................................................. XI PRESENTATION OF RESEARCH............................................................... XII SUMMARY ..................................................................................................XIV CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCING MUSIC FESTIVALS AS POSTMODERN SITES OF CONSUMPTION.............................................................................1 1.1 The Aim of the Research ................................................................................................................. 6 1.2 Consumer Society............................................................................................................................. 8 1.3 Consuming ‘Youth’........................................................................................................................ 10 1.4 Defining Youth .............................................................................................................................. -

Millicent Williamson Goldsmiths College University of London

WOMEN AND VAMPIRE FICTION: TEXTs, FANDOM AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF IDENTITY Millicent Williamson Goldsmiths College University of London Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD ABSTRACT This thesis examines what vampire fiction and vampire fandom offer to women and uses as a case study the accounts offered by women fans in New Orleans and Britain. Textual approaches to vampire fiction and femininity have largely proposed that just as the woman is punished by being positioned as passive and masochistic in the texts of Dracula, so too is the female viewer or reader of the texts. This thesis argues that such approaches are inadequate because they impose a singular ('Dracularesque') structure of meaning which both underestimates the variety of vampire fiction available and ignores the process of reading that women interested in the vampire figure engage in. It is argued, based on the women vampire fan's own textual interpretations, that the vampire can be read as a figure of pathos who elicits the fans' sympathy because of its predicament. It is further argued that this approach to the vampire appeals to the women because it brings into play a melodramatic structure which resonates with certain problematic experiences of feminine identity that are often suppressed in our culture and thus difficult to articulate. The figure of the vampire offers women fans both a channel for their creativity and a means of rebelling against the imposed norms of femininity. It is a well-rehearsed position in theories of fandom that the activity that fans engage in is a form of rebellion or resistance.