FINAL Dissertation JULY 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

112 Dance with Me 112 Peaches & Cream 213 Groupie Luv 311

112 DANCE WITH ME 112 PEACHES & CREAM 213 GROUPIE LUV 311 ALL MIXED UP 311 AMBER 311 BEAUTIFUL DISASTER 311 BEYOND THE GRAY SKY 311 CHAMPAGNE 311 CREATURES (FOR A WHILE) 311 DON'T STAY HOME 311 DON'T TREAD ON ME 311 DOWN 311 LOVE SONG 311 PURPOSE ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 1 PLUS 1 CHERRY BOMB 10 M POP MUZIK 10 YEARS WASTELAND 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 10CC THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 FT. SEAN PAUL NA NA NA NA 112 FT. SHYNE IT'S OVER NOW (RADIO EDIT) 12 VOLT SEX HOOK IT UP 1TYM WITHOUT YOU 2 IN A ROOM WIGGLE IT 2 LIVE CREW DAISY DUKES (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW DIRTY NURSERY RHYMES (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW FACE DOWN *** UP (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW ME SO HORNY (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW WE WANT SOME ***** (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 PAC 16 ON DEATH ROW 2 PAC 2 OF AMERIKAZ MOST WANTED 2 PAC ALL EYEZ ON ME 2 PAC AND, STILL I LOVE YOU 2 PAC AS THE WORLD TURNS 2 PAC BRENDA'S GOT A BABY 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (EXTENDED MIX) 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (NINETY EIGHT) 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (ORIGINAL VERSION) 2 PAC CAN'T C ME 2 PAC CHANGED MAN 2 PAC CONFESSIONS 2 PAC DEAR MAMA 2 PAC DEATH AROUND THE CORNER 2 PAC DESICATION 2 PAC DO FOR LOVE 2 PAC DON'T GET IT TWISTED 2 PAC GHETTO GOSPEL 2 PAC GHOST 2 PAC GOOD LIFE 2 PAC GOT MY MIND MADE UP 2 PAC HATE THE GAME 2 PAC HEARTZ OF MEN 2 PAC HIT EM UP FT. -

Interview with Kristina Arriaga De Bucholz Monthly Chat Is an Interview That Runs on the Times Opinion Pages

WWW.ALEXTIMES.COM MARCH 21, 2013 | 1 Vol. 9, No. 12 Alexandria’s only independent hometown newspaper MARCH 21, 2013 Emergency Water under the bridge responders warn of brain drain Increased benefit costs squeeze firefighters, police BY MELISSA QUINN Larry Lee’s career as a first responder in Alexandria began many years ago, but for the first time, the city’s budget issues have him grappling with the idea of early retirement. He started working in the city as a police officer in 1987, back when Alexandria may not have been the best place to raise a family. Drug use ran rampant, PHOTO/DERRICK PERKINS Longtime city resident Bert Ely has become the unofficial spokesman for residents against the water- he said, and it wasn’t uncom- front redevelopment plan. He has helped organize resident-led lawsuits against the city as well as formed mon for Lee to find himself re- Friends of the Alexandria Waterfront with Mark Mueller. sponding to stabbings or work- PHOTO/DERRICK PERKINS ing in the middle of a riot. The city’s historic waterfront is poised for redevelopment after the city council reapproved zoning and density changes along the shoreline. In 1998, Lee joined the fire Officials hope the move will short-circuit litigation surrounding the controversial waterfront plan. department, where he has re- City council reapproves hoping a supermajority would dozens from speaking out mained ever since. He expanded redevelopment plan accept the changes. Vice May- against the redevelopment Before me, his duties by signing on as the vice president of Alexandria or Allison Silberberg, who roadmap during Saturday’s generations BY DERRICK PERKINS campaigned against the plan, public hearing. -

The Parish Ofsaint Joan of Arc PARISH STAFF

PARISH STAFF Welcome Pastor: OUR MISSION Rev. Michael D. Joly Deacons: St. Joan of Arc is a Catholic Family of Rev. Mr. Mark Mueller Faith, alive in the Lord Jesus Christ Rev. Mr. Jim Satterwhite through His Mercy, His Love, His Administrative Assistant: Word, His Sacraments, all granted by Cherry Macababbad His Holy Spirit. We proclaim the joy Coordinator of Religious Education/ of the Gospel; we minister to the needs Ministerial Assistant: Jennifer Sanders of the Body of Christ, both within and Ministerial Assistant: Christine Ladnier outside the parish family, especially Youth & Young Adult Minister: Justin Pybus the poor who present a unique Music Director: Liam Lees opportunity for us to meet Christ. Bookkeeper: Gina Baird The Parish Custodian: Dave Payton of Saint Joan of Arc 315 Harris Grove Lane • Yorktown, Virginia 23692 Parish Office: 757-898-5570 • Fax: 757-898-0737 • Social Outreach: 757-898-1220 Office Hours: Monday-Thursday, 8:30-12:30 & 1:30-4:30 p.m. • Closed for lunch: 12:30-1:30 p.m.; Friday, 8:30-12:30 p.m. & 1:30-3:00 p.m. • Closed for lunch: 12:30-1:30 p.m. Web Page: http://www.stjoanofarcva.org • E-mail: [email protected] Mass Schedule Sacrament of Reconciliation Weekend Saturday: 4:30 p.m. Saturday – 5:30 p.m. Praise & Worship Sunday – 8:30 a.m. & 11:00 a.m. Wednesday: 7:00 p.m. Weekday First Friday Adoration Tuesday through Friday – 9:00 a.m. Friday: 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. SACRAMENTS Infant Baptism: Celebrated on the second and fourth weekend of each month; Saturday at 3:00 p.m. -

X by Song Title

INDEX BY SONG TITLE "The A Team", Theme from ....................................TflE A TEAM Adam 12 Theme ......................................................ADAM 12 Addams family Theme, The ..................................THE ADDAMS fAMlLY "Alf '. Theme from ....................................................ALF Ballad Of Davy Crockett, The ...............................DAVY CROCKETT Ballad Of led Clampett ........................................THE BEVERLY HILLBILLIES Bandstand Boogie. ................................................AMERICAN BANDSTAND Battlestar Galactica ...............................................BATTLESTAR GALACTICA "Beauty And The Beast". Theme from ..................BEAUTY AND THE BEAST "Ben Casey", Theme from .....................................BEN CASEY "Bewitched", Theme from ......................................BEWITCHED Bonanza.. ................................................................BONANZA Brady Bunch, The .............................................THE BRADY BUNCH Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 ................................FIRING LINE Bubbles In The Wine ..............................................THE LAWRENCE WELK SHOW Call To Glory ...........................................................CALL TO GLORY Casper The friendly Ghost ...................................CASE THE FRIENDLY GHOST Where Everybody Knows Your Name ...................CHEERS Chico And The Man ................................................CHIC AND THE MAN Chip 'N Dale Rescue Rangers Theme Song ........ CHIP 'N -

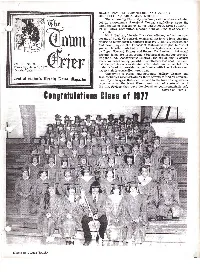

Congratulations Class A·F 1877

BLACK FLY PROBLEM/SHORELAND ZONING DISCUSSED AT AREA MMA MEETING The worsening Black Fly problem. and the often confusing details surrounding Shoreland Zoning regulations were the chief topics of discussion at the latest MMA Area 10 Legis lative Policy Committee meeting held on June 2 at the Milo Town Hall. Mark Mueller. Lincoln Town Councilman. and active pro ponent of Black Fly control. explained his town's long-standing efforts to bring about a solution to heavy Black F1y infestations that have plagued the Penobscot Watershed region in recent own years. Mueller detailed a bill in the legislature. sponsored by Reps. Richard Davies and Robert MacEachern. that would provide funds for researching a biological means for control ling the flies. According to Mueller, the bill originally sought funds for researching possible insecticides that could be used. Vol. 16. No. 23 but the provision was deleted after state environmental offi Thursday. June 9. cials refused to consider experiments with insecticides even Twenty Cents under tightly-controlled conditions. University of Maine entomologists Jeffrey Granett and Ivan McDaniel added details on their efforts to find an environ [rntral tlatnr'a lirrltly Nrws Sugnzittl' mentally safe agent that could be used in the fast flowing wate.r ways in which the black flies breed. Granett spoke of one of the insecticides they have developed as environmentally safe · Cont'd on Page 2 Congratulations Class a·f 1877 (Photo by Claude Trask) Page 2 June 9, 1977 THE TOWN CRIER TiiE TOWN CRIER is published each Thursday by the Milo Printing Company. We hope to be of help to the citizens of the towns € .Off1U1UH it !-f of our coverage area through NEWS, IN FORMATION and LOW PRICED ADVER ~""'P .i tal '1'7ew" TISING. -

PDF of Chuck's Credits

Chuck Wild LiquidMindMusic.com • ChuckWild.com Twitter: https://twitter.com/LiquidMindCW Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/OfficialLiquidMind.Chuck Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/9827942@N05/ Recording Artist/Composer: LIQUID MIND® Musical Healthcare® albums: (under license to Real Music®) Liquid Mind: Musical Healthcare® (collection + 1 song) - 2021 Liquid Mind XIII: Mindfulness - 2020 Liquid Mind XII: Peace – 2018 Liquid Mind XI: Deep Sleep - 2016 Liquid Mind: Relaxing Rain & Ocean Mixes - 2014 (Collection from previous albums) Liquid Mind X: Meditation – 2012 Dream: A Liquid Mind Experience - 2011 (collection of timed pieces from catalog) Liquid Mind IX: Lullaby - 2009 Relax: A Liquid Mind Experience - 2007 (collection from previous albums) Liquid Mind VIII: Sleep - 2006 Liquid Mind VII: Reflection - 2004 Liquid Mind VI: Spirit - 2003 Liquid Mind V: Serenity - 2001 Liquid Mind IV: Unity - 2000 Liquid Mind III: Balance - 1999 Slow World – 1996 (Liquid Mind II) Ambience Minimus – 1994 (Liquid Mind I) CONCERT/NEO-CLASSICAL REPERTOIRE: Los Angeles Fantasy for two pianos (1992) (two pianos) Oh Liberty! (2005) ( Patriotic anthem for tenor and symphony orchestra) Lullaby (2007) (Art Song) (Tenor & Piano) Prelude I: Evanescence (2009) (solo piano) Prelude II: Climbing the Wall (2009) (solo piano) Prelude III: Transfiguration (2009) (solo piano) Prelude IV: The Rabbit (2009) (solo piano) Prelude V: Of Two Minds (2009) (solo piano) Prelude VI: Pondering (2009) (solo piano) Prelude VII: Velvet Cascade (2009) (solo piano) Prelude VIII: Cross Your Fingers (2017) ) (solo piano) Prelude IX: Steeplechase (2017) ) (solo piano) Prelude X: I Love an Accent (2017) ) (solo piano) Sonata No. 1: Ballet of the Mind (2013-2016) (solo piano) Impromptu in Cm: Decidedly Indecisive (2017) (solo piano) Danse Disquo: An Awkward Excursion into the Recent Past (2017) (solo piano) Impromptu No. -

What Is Jazz Education

What Is at Stake in Jazz Education? Creative Black Music and the Twenty-First-Century Learning Environment DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Norman Michael Goecke, M.M., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Ryan T. Skinner William T. McDaniel Copyright by Norman Michael Goecke 2016 Abstract This dissertation aims to explore and describe, in ethnographic terms, some of the principal formal and non-formal environments in which jazz music is learned today. By elucidating the broad aesthetic, stylistic, and social landscapes of present-day jazz pedagogy, it seeks to encourage the revitalization and reorientation of jazz education, and of the cultural spaces in which it takes place. Although formal learning environments have increasingly supported the activities of the jazz community, I argue that this development has also entailed a number of problems, notably a renewal of racial tensions spurred on by 1) the under-representation of non-white students and faculty, especially black Americans; 2) the widespread adoption of 'color-blind' methodologies in formal music-learning environments, which serve to perpetuate ambivalence or apathy in the addressing of racial problems; 3) a failure adequately to address cultural studies related to the black heritage of jazz music; and 4) the perpetuation of a narrow vision of jazz music that privileges certain -

Automation of America's Offices, 1985-2000

Automation of America's Offices, 1985-2000 December 1985 NTIS order #PB86-185055 Recommended Citation: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, Automation of America Offices (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, OTA-CIT-287, December 1985). Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 85-600623 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 . Foreword Automation of America Offices, 1985-2000, assesses the consequences of the continuing and rapid introduction of information and telecommunications tech- nologies in offices: the workplace of about 45 million Americans. The use of com- puters and new communication systems in offices is bringing about fundamental changes in employment patterns, the skills needed for white-collar occupations, and the quality of worklife and the office environment. These changes will affect all industry sectors, since office work is a growing component of every industry as well as all public sector organizations. The study, requested by the Senate Committee on Labor and Human Re- sources and the House Committee on Education and Labor, will also be of interest to many other congressional committees because it addresses a wide range of sub- jects of concern to industry, government, and educational institutions, and to em- ployers, employees, and their organizations. OTA wishes to thank the many people and organizations that contributed to this assessment through advisory panels, workshops, interviews, and other means of sharing their information and experience with us. The final responsibil- ity for the study, however, rests with OTA. Director ///. Automation of America’s Offices Advisory Panel Charles E. Branscomb Henry C. -

Alexandria Gazette Packet

Alexandria Wellbeing Gazette Packet Page 28 25 Cents Serving Alexandria for over 200 years • A Connection Newspaper February 2, 2012 Lenny Harris: From Missing to Murdered Maryland man confesses to crime; three or four more suspects remain on the loose. By Michael Lee Pope Gazette Packet Photo by Photo ithin hours of upgrad- Wing the Lenny Harris by Photo missing person case to Max Deutsch a homicide investigation, the Prince George’s County Police De- Louise Krafft Louise partment announced the arrest of one man Tuesday afternoon, Jan. 31, and say they’re still looking for three or four more individuals. Zumba for Good Cause Monday night, officers picked up /Gazette Packet More than 100 participants danced Zumba through the late afternoon on Sunday at 49-year-old Linwood Johnson of the Carlyle Club. The event benefitted local charities through ACT’s Running Brooke Oxon Hill, Md., for questioning. Fund. More photos, story on page 4. He eventually confessed to the murder and is now facing first- degree murder charges. “It appears that the victim and Lenny Harris suspect in this case were known Up, Up and Away to each other, so this was not a shortly after 1 a.m. the day after complete stranger or random mur- he went missing. A few days later, der,” said Corporal Henry Tippett, the Alexandria Police Department Move to the “cloud” reaps Digital Cities Award. public information officer for the issued five more photographs of a Prince George’s white Dodge By Jeanne Theismann the 2011 Easter holiday weekend of Alexandria’s IT system when it County Police Caravan that Gazette Packet was approaching. -

2019 Yearbook & Media Guide

2019 YEARBOOK & MEDIA GUIDE MInnesota Golf Association 6550 York Ave. So. Suite. 211 Edina, Minnesota 55435 952-927-4643 800-642-4405 Fax: 952-927-9642 Editor W.P. Ryan Contributing Photographers Mark Brettingen Jeff Lawler Paul Markert W.P. Ryan Matt Seefeldt Peter Wong Contributing Writers Mike Fermoyle Nick Hunter W.P. Ryan Designer Karen Spruth Media Services [email protected] [email protected] 952-345-3966 Publisher Published by the Minnesota Golf Association, Inc. Copyright 2019 A young competitor tees off during the 2018 MPGA Junior Public Links Championship at Heritage Links Golf Club. 2019 MGA Yearbook and Media Guide mngolf.org 1 INSIDE THE 2019 MGA YEARBOOK & MEDIA GUIDE ABOUT THE MGA • 4-26 Message from the President 4 The MGA Story 8 MGA Officers 5 Allied Associations 9-11 TABLE OF CONTENTS OF TABLE MGA Executive Committee and Past Presidents 6 MGA Services 12-19 MGA Staff 7 MGA Awards 20-26 THE PLAYERS • 27-43 2018 MGA Players of the Year 28-30 MGA Male Player Profiles 34-38 MGA Player Point Distrbution 31-33 MGA Female Player Profiles 39-43 MINNESOTA CHAMPIONSHIPS • 44-291 (Event pages in 2019 chronological order throughout this chapter. Table of contest listings shown in association order) MINNESOTA GOLF ASSOCIATION MGA/PGA Cup Matches 62-65 MGA Women’s Amateur Four-Ball Championship 192-195 MGA Women’s Senior Amateur Four-Ball Championship 68-69 MGA Junior Team Championship 200-205 MGA Mid-Players’ Champioinship 96-99 MGA Women’s Senior Amateur Championship 214-219 MGA Senior Players’ Championship 100-103 MGA Amateur Four-Ball -

Various We Are the World Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various We Are The World mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock / Pop Album: We Are The World Country: Canada Released: 1985 Style: Soft Rock, Pop Rock, Synth-pop, Ballad MP3 version RAR size: 1824 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1444 mb WMA version RAR size: 1536 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 971 Other Formats: VOC RA DXD MP4 AC3 APE AC3 Tracklist Hide Credits We Are The World Accompanied By [Musician] – David Paich, Greg Phillinganes, Humberto Gatica, Ian Underwood, John Barnes, John Robinson , Louis Johnson, Marcus Ryles, Michael Boddicker, Michael Omartian, Michael Melvoin*, Paulinho Da Costa, Steve Porcaro, Tom BahlerArranged By [Rhythm Arrangements] – John Barnes, Quincy JonesArranged By [Solo Vocal Choreography] – Quincy Jones, Tom BahlerArranged By [Synthesizer Arrangements] – David Paich, Ian Underwood, John Barnes, Michael Boddicker, Michael Omartian, Quincy JonesArranged By [Vocal Choir Arrangements] – Michael JacksonArranged By [Vocal Choir] – Quincy Jones, Tom BahlerConductor, Producer – Quincy JonesCoordinator [Production Coordinator] – Jolie LevineCopyist – Doug Dana, Tom BrownEngineer – Humberto Gatica, John GuessExecutive- Producer [Executive Production Assistant] – Madeline RandolphHandclaps – Cathy Worthington, Elaine Phillinganes, Greg Phillinganes, James Ingram, Karla Phillinganes, Khaliq Glover, Marcel East*, Mark Ross , Steve –USA For A1 RayMastered By – Bernie GrundmanMixed By – Humberto GaticaMixed By 7:02 Africa [Assisted By] – Khaliq Glover, Larry Fergusson*Other [Production Assistant] – Mark Ross