What Is Jazz Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mike Mangini

/.%/&4(2%% 02):%3&2/- -".#0'(0%4$)3*4"%-&34&55*/(4*()54 7). 9!-!(!$25-3 VALUED ATOVER -ARCH 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE 0/5)& '0$64)*)"5 "$)*&7&5)&$-"44*$ 48*/(406/% "35#-",&: 5)&.&/503 50%%46$)&3."/ 45:-&"/%"/"-:4*4 $2%!-4(%!4%23 Ê / Ê" Ê," Ê/"Ê"6 , /Ê-1 -- (3&(03:)65$)*/40/ 8)&3&+";;41"45"/%'6563&.&&5 #6*-%:06308/ .6-5*1&%"-4&561 -ODERN$RUMMERCOM 3&7*&8&% 5"."4*-7&345"33&.0108&34530,&130-6%8*("5-"4130)"3%8"3&3*.4)05-0$."55/0-"/$:.#"-4 Volume 36, Number 3 • Cover photo by Paul La Raia CONTENTS Paul La Raia Courtesy of Mapex 40 SETTING SIGHTS: CHRIS ADLER Lamb of God’s tireless sticksman embraces his natural lefty tendencies. by Ken Micallef Timothy Saccenti 54 MIKE MANGINI By creating layers of complex rhythms that complement Dream Theater’s epic arrangements, “the new guy” is ushering in a bold and exciting era for the band, its fans, and progressive rock music itself. by Mike Haid 44 GREGORY HUTCHINSON Hutch might just be the jazz drummer’s jazz drummer— historically astute and futuristically minded, with the kind 12 UPDATE of technique, soul, and sophistication that today’s most important artists treasure. • Manraze’s PAUL COOK by Ken Micallef • Jazz Vet JOEL TAYLOR • NRBQ’s CONRAD CHOUCROUN • Rebel Rocker HANK WILLIAMS III Chuck Parker 32 SHOP TALK Create a Stable Multi-Pedal Setup 36 PORTRAITS NYC Pocket Master TONY MASON 98 WHAT DO YOU KNOW ABOUT...? Faust’s WERNER “ZAPPI” DIERMAIER One of Three Incredible 70 INFLUENCES: ART BLAKEY Prizes From Yamaha Drums Enter to Win We all know those iconic black-and-white images: Blakey at the Valued $ kit, sweat beads on his forehead, a flash in the eyes, and that at Over 5,700 pg 85 mouth agape—sometimes with the tongue flat out—in pure elation. -

Music Video As Black Art

IN FOCUS: Modes of Black Liquidity: Music Video as Black Art The Unruly Archives of Black Music Videos by ALESSANDRA RAENGO and LAUREN MCLEOD CRAMER, editors idway through Kahlil Joseph’s short fi lm Music Is My Mis- tress (2017), the cellist and singer Kelsey Lu turns to Ishmael Butler, a rapper and member of the hip-hop duo Shabazz Palaces, to ask a question. The dialogue is inaudible, but an intertitle appears on screen: “HER: Who is your favorite fi lm- Mmaker?” “HIM: Miles Davis.” This moment of Black audiovisual appreciation anticipates a conversation between Black popular cul- ture scholars Uri McMillan and Mark Anthony Neal that inspires the subtitle for this In Focus dossier: “Music Video as Black Art.”1 McMillan and Neal interpret the complexity of contemporary Black music video production as a “return” to its status as “art”— and specifi cally as Black art—that self-consciously uses visual and sonic citations from various realms of Black expressive culture in- cluding the visual and performing arts, fashion, design, and, obvi- ously, the rich history of Black music and Black music production. McMillan and Neal implicitly refer to an earlier, more recogniz- able moment in Black music video history, the mid-1990s and early 2000s, when Hype Williams defi ned music video aesthetics as one of the single most important innovators of the form. Although it is rarely addressed in the literature on music videos, the glare of the prolifi c fi lmmaker’s infl uence extends beyond his signature lumi- nous visual style; Williams distinguished the Black music video as a creative laboratory for a new generation of artists such as Arthur Jafa, Kahlil Joseph, Bradford Young, and Jenn Nkiru. -

BRIEF STUDIES and REPORTS the Perry George Lowery / Scott Joplin

459 BRIEF STUDIES and REPORTS The Perry George Lowery / Scott Joplin Connection: New Information on an Important African American Cornetist Richard I. Schwartz The author of this article has previously discussed the life and career of Perry George Lowery (1869-1942) in the Historic Brass Society .f ournal (vol. 12 [2002] : 61-88). The present article is designed to provide supplementary information about his circus career and his surprising professional association with Scott Joplin (1868-1919). It has become apparent to this author that a relationship of strong mutual respect and friendship developed between Perry George Lowery and Scott Joplin during the early twentieth century. P.G. Lowery was renowned for his abilities not only as a cornetist, but also as a conductor ofmany brass bands, consisting of the best African American band musicians in the entertainment world.' Scott Joplin's achievements are many and have been researched extensively by several authors.' One of the few articles in The Indianapolis Freeman3 documenting a friendship between Lowery and Joplin states that "P.G. Lowery, assistant manager of Swain's Nashville Students was the special guest of Scott Joplin, the ragtime king and author of the following hits: `Maple Leaf Rag,' 'Easy Winner,' Peacherine Rag,' 'Sun-flower Slowdrag,' and 'A Blizzard'." Much has been written about all of these compositions with the exception of the last one: no piece entitled A Blizzard has survived and according to Edward A. Berlin4 this reference is the only known mention of it. Lowery extolled the praises of Joplin's works in The Indianapolis Freeman (16 November 1901, p. -

Wynton Marsalis Happy Birthday Transcription Pdf Free

Wynton Marsalis Happy Birthday Transcription Pdf Free 1 / 4 Wynton Marsalis Happy Birthday Transcription Pdf Free 2 / 4 3 / 4 Print and download Caravan sheet music by Wynton Marsalis arranged for Trumpet or Piano. Instrument/Piano/Chords, and Transcribed Solo in Bb Major. Your high-resolution PDF file will be ready to download in the original published key . Song Spotlight Signature Artists Sales and Promotions Free Sheet Music.. Sep 6, 2018 . Marsalis at the Oskar Schindler Performing Arts Center Seventh Annual Jazz Festival in 2009. Background information. Birth name, Wynton.. essential and the necessary references are in general noted in the pdf. to present this unique collection of transcriptions which he has compiled over a span of . Several years before Wynton Marsalis gained headlines for helping to revive . Baker took the Armstrong role, comfortably confounding the date on his birth.. Transcription of Wynton Kelly's piano solo on the Bb blues tune "Kelly Blue" from . Wynton Marsalis and the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra Monday, March 18, . Father of Jazz Though the precise birth of jazz is still shrouded in mystery,.. Chords for Wynton Marsalis Playing Happy Birthday - transcription of the improvisation. Play along with guitar, ukulele, or piano with interactive chords and.. Amazon.com: Wynton Marsalis - Omnibook: for B-flat Instruments . members save up to 20% on diapers, baby food, & more Baby Registry Kids Birthdays . on orders over $25or get FREE Two- Day Shipping with Amazon Prime . Trumpet Omnibook: For B-Flat Instruments Transcribed Exactly from Artist Recorded Solos.. 12 2016 . Wynton Marsalis - Moanin Trumpet Solo [Free PDF] 02:22 . -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

The Hornet, 1923 - 2006 - Link Page Previous Volume 44, Issue 16 Next Volume 44, Issue 18

Foxworthy Named to Senate Post THE\ . No. 6 Card \ ^ .. Final Required for Examinations Book Purchase Start Jan. 21 7eV OLI ullerto eatlifornia, Frida, January 1, 19 Ce Vol. XLIV Fullerton, California, Friday, January 14, 1966 No. 17 Shelley Manne and His Men Robert Foxworthy Bring Modern Jazz to FJC Chosen President The contemporary, modern jazz Manne, a well-known drummer, BY JUDY CZUCHTA had a Faculty Senate. Our Senate of Shelly Manne and his Men was started his career in Hollywood will grow because it is new." Mr. spotlighted in the College Hour and gained renown for Shelly's English teacher Robert E. Fox- Foxworthy continued by at Louis E. Plummer Auditorium Manne-hole, which is currently a worthy has been elected as the saying, "Basil C. Hedrick, and I are work- yesterday. favorite bistro for jazz enthusiasts. first president of FJC's Faculty He worked his way up to become Senate. Phil L. Snyder, social sci- ing together on this matter ... our one of the top names in jazz in ences, was elected vice president main objective $s student-teacher Southern California. and Leroy J. Cordrey, counseling, welfare." Dr. Hedrick, language depart- Noted for their own interpre- as secretary. ment, is president of the Faculty tations and adaptations/of modern The newly elected president con- Club on campus and was instru- jazz and show tunes, Manne and ducted his first meeting last month mental in helping to establish the his Men are known by many as and the new organization's agenda new Faculty Senate. jazz connoisseurs. was discussed. -

VPI HR-X Turntable & JMW12.6 Tonearm

stereophile.com http://www.stereophile.com/turntables/506vpi#5kC628WHPF3lKHV2.97 VPI HR-X turntable & JMW12.6 tonearm VPI Industries' TNT turntable and JMW Memorial tonearm have evolved through several iterations over the last two decades. Some changes have been large, such as the deletion of the three-pulley subchassis and the introduction of the SDS motor controller. Others have been invisible—a change in bearing or spindle material, for example, or the way the bearing attaches to the plinth. And, as longtime Stereophile readers know, I've been upgrading and evolving along with VPI, most recently reporting on the TNT V-HR turntable (Stereophile, December 2001). But about the time I was expecting the next iteration, designer Harry Weisfeld threw me a curve by unveiling a completely new turntable design, the HR-X. First shown in prototype form at Stereophile's Home Entertainment 2002 show in New York City, the HR-X is a stunning, milled-from-aluminum showcase of everything Weisfeld has learned from designing turntables for the past 25 years. Nuts & bolts Although the HR-X is a clean-slate design, it was obviously informed by the TNT. There are four corner towers with internal pneumatic bladders, a huge platter belt-driven by an outboard motor and flywheel, and a JMW tonearm mounted directly to a massive plinth. Beyond that basic configuration, however, everything is different— rethought, improved, optimized, and executed to the highest standard possible. It's immediately obvious that even VPI's workmanship and cosmetics have been raised to new levels: the TNT was well-built and solid; the HR-X is striking and sumptuous. -

The Jazz Record

oCtober 2019—ISSUe 210 YO Ur Free GUide TO tHe NYC JaZZ sCene nyCJaZZreCord.Com BLAKEYART INDESTRUCTIBLE LEGACY david andrew akira DR. billy torn lamb sakata taylor on tHe Cover ART BLAKEY A INDESTRUCTIBLE LEGACY L A N N by russ musto A H I G I A N The final set of this year’s Charlie Parker Jazz Festival and rhythmic vitality of bebop, took on a gospel-tinged and former band pianist Walter Davis, Jr. With the was by Carl Allen’s Art Blakey Centennial Project, playing melodicism buoyed by polyrhythmic drumming, giving replacement of Hardman by Russian trumpeter Valery songs from the Jazz Messengers songbook. Allen recalls, the music a more accessible sound that was dubbed Ponomarev and the addition of alto saxophonist Bobby “It was an honor to present the project at the festival. For hardbop, a name that would be used to describe the Watson to the band, Blakey once again had a stable me it was very fitting because Charlie Parker changed the Jazz Messengers style throughout its long existence. unit, replenishing his spirit, as can be heard on the direction of jazz as we know it and Art Blakey changed By 1955, following a slew of trio recordings as a album Gypsy Folk Tales. The drummer was soon touring my conceptual approach to playing music and leading a sideman with the day’s most inventive players, Blakey regularly again, feeling his oats, as reflected in the titles band. They were both trailblazers…Art represented in had taken over leadership of the band with Dorham, of his next records, In My Prime and Album of the Year. -

Big Black Pigpile Mp3, Flac, Wma

Big Black Pigpile mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Pigpile Country: US Released: 1992 Style: Industrial, Noise MP3 version RAR size: 1119 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1815 mb WMA version RAR size: 1934 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 569 Other Formats: MMF VOX ADX MP2 XM MP4 AIFF Tracklist A1 Fists Of Love A2 L Dopa A3 Passing Complexion A4 Dead Billy A5 Cables A6 Bad Penny B1 Pavement Saw B2 Kerosene B3 Steelworker B4 Pigeon Kill B5 Fish Fry B6 Jordan, Minnesota Companies, etc. Record Company – Southern Studios Ltd. Pressed By – MPO Recorded At – Hammersmith Clarendon Notes Recorded at the Hammersmith Clarendon, London, England in Summer 1987. White label in plain white sleeve with New Release letter from Southern Studios, London which has typed tracklist Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Runout Etchings Side A): MPO TG 81 A1 "A Dearth of Jon Spencer or What?" Matrix / Runout (Runout Etchings Side B): MPO TG 81 B1 "Please Increase Playback Volume 2db" Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year TG81 Big Black Pigpile (LP, Album) Touch And Go TG81 US 1992 TG81 Big Black Pigpile (LP, Album, TP) Touch And Go TG81 US 1992 TG81C Big Black Pigpile (Cass) Touch And Go TG81C US 1992 TG81 Big Black Pigpile (LP, Album, RP) Touch And Go TG81 US Unknown SENTO YU-1 Big Black Pigpile (CD, Album) Sento SENTO YU-1 Japan 1992 Related Music albums to Pigpile by Big Black Clash, The - (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais Alexander O'Neal - Live At The Hammersmith Apollo - London Balaam And The Angel - Live At The Clarendon Venom - Fuckin' Hell At Hammersmith The Human League - London Hammersmith Palais 22.5.80 Killing Joke - Live At The Hammersmith Apollo 16.10.2010 Volume 1 Motörhead - No Sleep 'Til Hammersmith Danzig - Die Die My Darling Big Black - Songs About Fucking Venom - Live In Hammersmith Odeon London 08.10.85. -

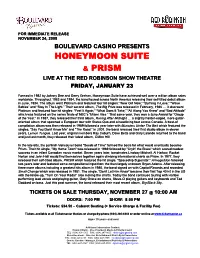

Honeymoon Suite & Prism

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NOVEMBER 24, 2008 BOULEVARD CASINO PRESENTS HONEYMOON SUITE & PRISM LIVE AT THE RED ROBINSON SHOW THEATRE FRIDAY, JANUARY 23 Formed in 1982 by Johnny Dee and Derry Grehan, Honeymoon Suite have achieved well over a million album sales worldwide. Throughout 1983 and 1984, the band toured across North America releasing their self-titled debut album in June, 1984. The album went Platinum and featured four hit singles: “New Girl Now,” “Burning In Love,” “Wave Babies” and “Stay In The Light.” Their second album, The Big Prize was released in February, 1986 … it also went Platinum and featured four hit singles: “Feel It Again,” “What Does It Take,” “All Along You Knew” and “Bad Attitude” which was featured on the series finale of NBC’s “Miami Vice.” That same year, they won a Juno Award for “Group of the Year.” In 1987, they released their third album, Racing After Midnight … a slightly harder-edged, more guitar- oriented album that spawned a European tour with Status Quo and a headlining tour across Canada. A best-of compilation album was then released in 1989 followed a year later with Monsters Under The Bed which featured the singles, “Say You Don’t Know Me” and “The Road.” In 2001, the band released their first studio album in eleven years, Lemon Tongue. Last year, original members Ray Coburn, Dave Betts and Gary Lalonde returned to the band and just last month, they released their latest album, Clifton Hill. In the late 60s, the punkish Vancouver band "Seeds of Time" formed the basis for what would eventually become Prism. -

Enroll Today!

FALL 1001 East Oregon Road 2016 CATALOG Lititz, PA 17543-9206 Capital Region | Lancaster County FALL 2016 CATALOG ENROLL TODAY! 717.381.3577 Lifelong Learning Courses, email: [email protected] | web: thepathwaysinstitute.org Excursions, & Service Projects for Adults 55+ in Lancaster County. Lifelong Learning Courses, Excursions, & Service Projects for Adults 55+ in Lancaster County. TABLE OF CONTENTS > TABLE OF PURPOSE/MISSION > PURPOSE/MISSION DIRECTOR’S WELCOME 1 CONTENTS > MEMBERSHIP PURPOSE/MISSION 2 > DIRECTOR’S MEMBERSHIP 2-3 WELCOME We commit to these values as we honor God in REGISTRATION 3-4 our service to others: PATHWAYS INSTITUTE FOR LIFELONG JOY: Nurturing an atmosphere which is positive, PROCEDURES 4-5 LEARNING MISSION AND PURPOSE hopeful and thankful, while delighting in serving DIRECTIONS 6 DIRECTOR’S WELCOME The mission of the Pathways Institute for Lifelong others, fulfilling responsibilities and celebrating life. Learning® is to foster with persons 55+ a quest for Thank you for your interest in the Pathways COURSES & EVENTS BY TOPIC lifelong learning that enriches the mind and spirit to COMPASSION: Demonstrating Christ-like love and ® (SEPTEMBER 7 – DECEMBER 15) 7-18 Institute for Lifelong Learning ! pursue wisdom, service, and understanding. concern in our relationships, serving one another with grace, humility, gentleness and sensitivity in a manner History & Culture 7-9 The Pathways Institute provides adults age 55 Recognizing that older adults have much to celebrate, which respects diversity and honors the dignity and Local History 10-12 & better with educational & lifelong learning discover, and share, the Pathways Institute for worth of everyone. Current Topics & Discussions 12 opportunities in an environment conducive to Lifelong Learning was established by Messiah Lifeways to find meaningful use of their talents and INTEGRITY: Committing ourselves to be honest, Nature & Science 12-13 discussion and sharing. -

A History of Music in Old Mount Vernon, Ohio with Particular Attention to Woodward Hall and the Nineteenth-Century American Opera House

A HISTORY OF MUSIC IN OLD MOUNT VERNON, OHIO WITH PARTICULAR ATTENTION TO WOODWARD HALL AND THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN OPERA HOUSE A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Elizabeth Bleecker McDaniel, B.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2003 Master's Examination Committee Approved by Dr. Graeme M. Boone, Adviser Dr. Charles M. Atkinson _________________________ Adviser Mr. Christopher R. Weait School of Music ABSTRACT During the antebellum period, the town of Mount Vernon, Ohio had a flourishing music scene that included performances by both local amateur societies and professional touring groups. When Woodward Hall, located on the top floor of a four-story commercial building, opened its doors to the public in 1851, it provided the town with its first dedicated theater. Newspaper items and other early sources show that the hall was a focus of public culture in the 1850s, hosting concerts, plays, lectures, and art exhibits as well as community activities including dances, church fundraisers, and school exhibitions. The early source materials for Mount Vernon, however, like those for many small towns, are lacunary, and especially so in the case of Woodward Hall. These shortcomings are compensated, to some extent, by materials relating to theaters of similar size and age in other towns, which offer points of comparison for the Woodward and prove it to be a typical mid-nineteenth-century American theater in some respects, and a distinctive one in others. Modern-day music histories have heretofore been silent on the subject of music and opera houses in small towns despite Oscar Sonneck’s call, some ninety years ago, for local music historiography as a necessary first step in creating a complete history of American music.