Considerations for the Development of Plug-In Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure for Consumers- a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vehicle Conversions, Retrofits, and Repowers ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, and REPOWERS

What Fleets Need to Know About Alternative Fuel Vehicle Conversions, Retrofits, and Repowers ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, AND REPOWERS Acknowledgments This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 with Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, the Manager and Operator of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. This work was made possible through funding provided by National Clean Cities Program Director and DOE Vehicle Technologies Office Deployment Manager Dennis Smith. This publication is part of a series. For other lessons learned from the Clean Cities American Recovery and Reinvestment (ARRA) projects, please refer to the following publications: • American Recovery and Reinvestment Act – Clean Cities Project Awards (DOE/GO-102016-4855 - August 2016) • Designing a Successful Transportation Project – Lessons Learned from the Clean Cities American Recovery and Reinvestment Projects (DOE/GO-102017-4955 - September 2017) Authors Kay Kelly and John Gonzales, National Renewable Energy Laboratory Disclaimer This document is not intended for use as a “how to” guide for individuals or organizations performing a conversion, repower, or retrofit. Instead, it is intended to be used as a guide and resource document for informational purposes only. VEHICLE TECHNOLOGIES OFFICE | cleancities.energy.gov 2 ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, AND REPOWERS Table of Contents Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................................5 -

Morgan Ellis Climate Policy Analyst and Clean Cities Coordinator DNREC [email protected] 302.739.9053

CLEAN TRANSPORTATION IN DELAWARE WILMAPCO’S OUR TOWN CONFERENCE THE PRESENTATION 1) What are alterative fuels? 2) The Fuels 3) What’s Delaware Doing? WHAT ARE ALTERNATIVE FUELED VEHICLES? • “Vehicles that run on a fuel other than traditional petroleum fuels (i.e. gas and diesel)” • Propane • Natural Gas • Electricity • Biodiesel • Ethanol • Hydrogen THERE’S A FUEL FOR EVERY FLEET! DELAWARE’S ALTERNATIVE FUELS • “Vehicles that run on a fuel other than traditional petroleum fuels (i.e. gas and diesel)” • Propane • Natural Gas • Electricity • Biodiesel • Ethanol • Hydrogen THE FUELS PROPANE • By-Product of Natural Gas • Compressed at high pressure to liquefy • Domestic Fuel Source • Great for: • School Busses • Step Vans • Larger Vans • Mid-Sized Vehicles COMPRESSED NATURAL GAS (CNG) • Predominately Methane • Uses existing pipeline distribution system to deliver gas • Good for: • Heavy-Duty Trucks • Passenger cars • School Buses • Waste Management Trucks • DNREC trucks PROPANE AND CNG INFRASTRUCTURE • 8 Propane Autogas Stations • 1 CNG Station • Fleet and Public Access with accounts ELECTRIC VEHICLES • Electricity is considered an alternative fuel • Uses electricity from a power source and stores it in batteries • Two types: • Battery Electric • Plug-in Hybrid • Great for: • Passenger Vehicles EV INFRASTRUCTURE • 61 charging stations in Delaware • At 26 locations • 37,000 Charging Stations in the United States • Three types: • Level 1 • Level 2 • D.C. Fast Charging TYPES OF CHARGING STATIONS Charger Current Type Voltage (V) Charging Primary Use Time Level 1 Alternating 120 V 2 to 5 miles Current (AC) per hour of Residential charge Level 2 AC 240 V 10 to 20 miles Residential per hour of and charge Commercial DC Fast Direct Current 480 V 60 to 80 miles (DC) per 20 min. -

Understanding Long-Term Evolving Patterns of Shared Electric

Experience: Understanding Long-Term Evolving Patterns of Shared Electric Vehicle Networks∗ Guang Wang Xiuyuan Chen Fan Zhang Rutgers University Rutgers University Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced [email protected] [email protected] Technology, CAS [email protected] Yang Wang Desheng Zhang University of Science and Rutgers University Technology of China [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT CCS CONCEPTS Due to the ever-growing concerns on the air pollution and • Networks → Network measurement; Mobile networks; energy security, many cities have started to update their Cyber-physical networks. taxi fleets with electric ones. Although environmentally friendly, the rapid promotion of electric taxis raises prob- KEYWORDS lems to both taxi drivers and governments, e.g., prolonged Electric vehicle; mobility pattern; charging pattern; evolving waiting/charging time, unbalanced utilization of charging experience; shared autonomous vehicle infrastructures and reduced taxi supply due to the long charg- ing time. In this paper, we make the first effort to understand ACM Reference Format: the long-term evolving patterns through a five-year study Guang Wang, Xiuyuan Chen, Fan Zhang, Yang Wang, and Desh- on one of the largest electric taxi networks in the world, i.e., eng Zhang. 2019. Experience: Understanding Long-Term Evolving the Shenzhen electric taxi network in China. In particular, Patterns of Shared Electric Vehicle Networks. In The 25th Annual we perform a comprehensive measurement investigation International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking (Mo- called ePat to explore the evolving mobility and charging biCom ’19), October 21–25, 2019, Los Cabos, Mexico. ACM, New York, patterns of electric vehicles. -

How Practical Are Alternative Fuel Vehicles?

How Practical Are Alternative Fuel Vehicles? Many of us have likely considered an alternative fuel vehicle at some point in our lives. Balancing the positives and negatives is a tricky process and varies greatly based on our personal situations. However, many of the negatives that previously created hesitancy have changed in recent years. Below, we have outlined a few of the most commonly mentioned negatives regarding the two leading alternative fuel vehicle types: Flex Fuel vehicles and Electric/Hybrid vehicles. Then, you can decide for yourself whether one of these vehicle types are practical for you! Cost – How much does the vehicle cost to purchase and operate? Flex Fuel: Flex Fuel vehicles typically cost about the same as a gasoline vehicle.1 For fuel cost, E85 typically costs slightly less than gasoline, however, due to decreased efficiency has a slightly higher cost per mile than gasoline.2 Overall, a Flex Fuel vehicle is likely to be slightly more expensive than a gasoline counterpart. Electric/Hybrid: This situation varies quite a bit depending on where you live. Electric vehicles and hybrid vehicles often cost considerably more than a conventional gasoline vehicle. For example, a plug-in hybrid will cost around $4000-$8000 more than a conventional model.3 However, there are federal rebates and local rebates that can refund thousands of dollars from the purchase price. Electric/Hybrid vehicles also tend to save money on fuel, with the possibility of saving thousands of dollars over the lifetime of the vehicle.4 Whether these rebates and fuel cost savings will eventually account for the higher purchase price can be estimated with comparison tools. -

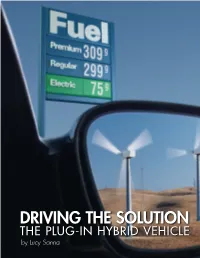

EPRI Journal--Driving the Solution: the Plug-In Hybrid Vehicle

DRIVING THE SOLUTION THE PLUG-IN HYBRID VEHICLE by Lucy Sanna The Story in Brief As automakers gear up to satisfy a growing market for fuel-efficient hybrid electric vehicles, the next- generation hybrid is already cruis- ing city streets, and it can literally run on empty. The plug-in hybrid charges directly from the electricity grid, but unlike its electric vehicle brethren, it sports a liquid fuel tank for unlimited driving range. The technology is here, the electricity infrastructure is in place, and the plug-in hybrid offers a key to replacing foreign oil with domestic resources for energy indepen- dence, reduced CO2 emissions, and lower fuel costs. DRIVING THE SOLUTION THE PLUG-IN HYBRID VEHICLE by Lucy Sanna n November 2005, the first few proto vide a variety of battery options tailored 2004, more than half of which came from Itype plugin hybrid electric vehicles to specific applications—vehicles that can imports. (PHEVs) will roll onto the streets of New run 20, 30, or even more electric miles.” With growing global demand, particu York City, Kansas City, and Los Angeles Until recently, however, even those larly from China and India, the price of a to demonstrate plugin hybrid technology automakers engaged in conventional barrel of oil is climbing at an unprece in varied environments. Like hybrid vehi hybrid technology have been reluctant to dented rate. The added cost and vulnera cles on the market today, the plugin embrace the PHEV, despite growing rec bility of relying on a strategic energy hybrid uses battery power to supplement ognition of the vehicle’s potential. -

Gasoline-Electric Hybrid Synergy Drive

Gasoline-Electric Hybrid Synergy Drive AHV40 Series Foreword In March 2006, Toyota released the Toyota CAMRY gasoline-electric hybrid vehicle in North America. Except where noted in this guide, basic vehicle systems and features for the CAMRY hybrid are the same as those on the conventional, non-hybrid, Toyota CAMRY. To educate and assist emergency responders in the safe handling of the CAMRY hybrid technology, Toyota published this CAMRY hybrid Emergency Response Guide. High voltage electricity powers the electric motor, generator, A/C compressor, and inverter/converter. All other automotive electrical devices such as the headlights, power steering, horn, radio, and gauges are powered from a separate 12 Volts battery. Numerous safeguards have been designed into the CAMRY to help ensure the high voltage, approximately 245 Volts, Nickel Metal Hydride (NiMH) Hybrid Vehicle (HV) battery pack is kept safe and secure in an accident. Additional topics contained in the guide include: N Toyota CAMRY identification. N Major hybrid component locations and descriptions. By following the information in this guide, dismantlers will be able to handle the CAMRY hybrid-electric vehicle as safely as the dismantling of a conventional gasoline engine automobile. ¤ 2006 Toyota Motor Corporation All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced or copied, in whole or in part, without the written permission of Toyota Motor Corporation ii Table of Contents About the CAMRY.........................................................................................................................1 -

Electric Vehicles: a Primer on Technology and Selected Policy Issues

Electric Vehicles: A Primer on Technology and Selected Policy Issues February 14, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46231 SUMMARY R46231 Electric Vehicles: A Primer on Technology and February 14, 2020 Selected Policy Issues Melissa N. Diaz The market for electrified light-duty vehicles (also called passenger vehicles; including passenger Analyst in Energy Policy cars, pickup trucks, SUVs, and minivans) has grown since the 1990s. During this decade, the first contemporary hybrid-electric vehicle debuted on the global market, followed by the introduction of other types of electric vehicles (EVs). By 2018, electric vehicles made up 4.2% of the 16.9 million new light-duty vehicles sold in the United States that year. Meanwhile, charging infrastructure grew in response to rising electric vehicle ownership, increasing from 3,394 charging stations in 2011 to 78,301 in 2019. However, many locations have sparse or no public charging infrastructure. Electric motors and traction battery packs—most commonly made up of lithium-ion battery cells—set EVs apart from internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs). The battery pack provides power to the motor that drives the vehicle. At times, the motor acts as a generator, sending electricity back to the battery. The broad categories of EVs can be identified by whether they have an internal combustion engine (i.e., hybrid vehicles) and whether the battery pack can be charged by external electricity (i.e., plug-in electric vehicles). The numerous vehicle technologies further determine characteristics such as fuel economy rating, driving range, and greenhouse gas emissions. EVs can be separated into three broad categories: Hybrid-electric vehicles (HEVs): The internal combustion engine primarily powers the wheels. -

The Toyota Prius Plug-In HEV: a Plug-In Hybrid Electric Car in NREL's Advanced Technology Vehicle Fleet (Fact Sheet), Transp

The Toyota Prius Plug-in HEV A plug-in hybrid electric car in NREL’s advanced technology vehicle fleet Toyota Prius Plug-in HEV Curb Weight 3278 lb Toyota Prius plug-in hybrid electric vehicle. Length 175.5 in. Photo from Atlantic County Utilities Authority, NREL/PIX 18311 Highlights Width 68.7 in. Height 58.7 in. The Toyota Prius plug-in hybrid electric vehicle at the NREL’s advanced vehicle fleet U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Peak Motor Power 80 hp features promising technologies Laboratory (NREL) is part of a worldwide 600-vehicle Motor Location Front to increase efficiency and reduce demonstration project. In partnership with the University emissions—all without sacrificing Engine Power 98 hp of Colorado, NREL uses the vehicle for grid-integration safety or comfort. The fleet serves Electric Range 13 mi studies and demonstrating plug-in vehicle synergies as a technology showcase, helping Seating 5 people with renewable energy. visitors learn about innovative Payload 26.1 ft3 Plug-in electric vehicles—including all-electric vehicles and vehicles that are available today Electric Top Speed 60 mph plug-in hybrid electric vehicles—provide a new opportu- or are in development. Vehicles U.S. Debut 2012 yr nity to reduce oil consumption by drawing on power from in the fleet are representative of Battery Capacity 5.2 kWh the electric grid. To maximize the benefits, the emerging current, advanced, prototype, vehicle-charging infrastructure must provide access to and emerging technologies. Battery Voltage 345.6 V Battery Warranty 8 yr or 100,000 mi clean electricity generated from renewable sources. -

Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicle Value Proposition Study

DOCUMENT AVAILABILITY Reports produced after January 1, 1996, are generally available free via the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Information Bridge: Web site: http://www.osti.gov/bridge Reports produced before January 1, 1996, may be purchased by members of the public from the following source: National Technical Information Service 5285 Port Royal Road Springfield, VA 22161 Telephone: 703-605-6000 (1-800-553-6847) TDD: 703-487-4639 Fax: 703-605-6900 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.ntis.gov/support/ordernowabout.htm Reports are available to DOE employees, DOE contractors, Energy Technology Data Exchange (ETDE) representatives, and International Nuclear Information System (INIS) representatives from the following source: Office of Scientific and Technical Information P.O. Box 62 Oak Ridge, TN 37831 Telephone: 865-576-8401 Fax: 865-576-5728 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.osti.gov/contact.html This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. -

The 'Renewables' Challenge

The ‘Renewables’ Challenge - Biofuels vs. Electric Mobility Hinrich Helms ifeu - Institut für Energie- und Umweltforschung Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Udo Lambrecht ifeu - Institut für Energie- und Umweltforschung Heidelberg, Germany Nils Rettenmaier ifeu - Institut für Energie- und Umweltforschung Heidelberg, Germany Summary Electric vehicles are considered as a key technology for sustainable transport. The use of biofuels in vehicles with con- ventional combustion engines, however, also offers the possibility for a substantial reduction of greenhouse gas emis- sions, without requiring costly batteries and long charging times and without significantly limiting the driving range. A comparison of environmental impacts between both options needs to be based on a life cycle perspective. First screen- ing results presented in this paper show that a diesel car fuelled with RME has considerably lower climate impacts than a comparable battery electric vehicle charged with average German electricity. On the other hand, the use of RME has disadvantages in other impacts categories such as eutrophication. Battery electric vehicles charged with renewable electricity in turn have the best climate impact balance of the considered options and also show among the lowest im- pacts in eutrophication. However, other biofuels such as palm oil and the use of biomass residues offer further reduc- tion potentials, but possibly face limited resources and land use changes. 1. Introduction man Federal Government has therefore set the target of one million electric vehicles in Germany by 2020. Mobility is an important basis for many economic and On the other hand, the use of biofuels in vehicles with private activities and thus a crucial part of our life. -

The Supply Chain for Electric Vehicle Batteries

United States International Trade Commission Journal of International Commerce and Economics December 2018 The Supply Chain for Electric Vehicle Batteries David Coffin and Jeff Horowitz Abstract Electric vehicles (EVs) are a growing part of the passenger vehicle industry due to improved technology, customer interest in reducing carbon footprints, and policy incentives. EV batteries are the key determinant of both the range and cost of the vehicle. This paper explains the importance of EV batteries, describes the structure of the EV battery supply chain, examines current limitations in trade data for EV batteries, and estimates the value added to EV batteries for EVs sold in the United States. Keywords: motor vehicles, cars, passenger vehicles, electric vehicles, vehicle batteries, lithium- ion batteries, supply chain, value chain. Suggested citation: Coffin, David, and Jeff Horowitz. “The Supply Chain for Electric Vehicle Batteries.” Journal of International Commerce and Economics, December 2018. https://www.usitc.gov/journals. This article is the result of the ongoing professional research of USITC staff and is solely meant to represent the opinions and professional research of the authors. It is not meant to represent in any way the views of the U.S. International Trade Commission, any of its individual Commissioners, or the United States Government. Please direct all correspondence to David Coffin and Jeff Horowitz, Office of Industries, U.S. International Trade Commission, 500 E Street SW, Washington, DC 20436, or by email to [email protected] and [email protected]. The Supply Chain for Electric Vehicle Batteries Introduction Supply chains spreading across countries have added complexity to tracking international trade flows and calculating the value each country receives from a particular good. -

A U.S. Consumer's Guide to Electric Vehicle Charging

CONSUMER GUIDE TO ELECTRIC VEHICLES JUNE 2021 11570437 WHY BUY AN ELECTRIC CAR? Electric vehicles (EVs) are fun to drive, safe, comfortable, and convenient to refuel. They also cost less to operate per mile and produce no tailpipe emissions. Today’s electric cars do everything a gas car can do—and more. Most are high-performing vehicles with silent, instant torque, superb handling, and the latest technology and safety features. Most can travel 200–250 miles on a charge; many can go farther. Most EV drivers prefer to charge at home for its convenience and savings. A growing national network of public charging sites enables more consumers—even those who can’t plug in at home—to consider purchasing an EV. Because EVs are powered by electricity instead of gasoline, they shift our energy reliance to domestic sources while also reducing emissions. Cutting vehicle emissions is especially critical in communities adjacent to heavily trafficked roadways. As local power generation grows cleaner, every electric car charged on that grid gets cleaner too—and the broader public health and climate benefits increase. Electrifying light-duty transport would reduce overall greenhouse gas emissions by 17% relative to 2018 levels. EV 101 This guide highlights the two types of electric vehicles that plug into the grid to recharge their batteries. They are battery-electric (or all-electric) vehicles and plug-in hybrids. All-electric vehicles are powered solely Plug-in hybrids pair an electric motor by an electric motor and battery. They and battery with an internal-combustion burn no gasoline or diesel fuel, so they engine.