Electric Vehicles: the Portland Way

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vehicle Conversions, Retrofits, and Repowers ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, and REPOWERS

What Fleets Need to Know About Alternative Fuel Vehicle Conversions, Retrofits, and Repowers ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, AND REPOWERS Acknowledgments This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 with Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, the Manager and Operator of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. This work was made possible through funding provided by National Clean Cities Program Director and DOE Vehicle Technologies Office Deployment Manager Dennis Smith. This publication is part of a series. For other lessons learned from the Clean Cities American Recovery and Reinvestment (ARRA) projects, please refer to the following publications: • American Recovery and Reinvestment Act – Clean Cities Project Awards (DOE/GO-102016-4855 - August 2016) • Designing a Successful Transportation Project – Lessons Learned from the Clean Cities American Recovery and Reinvestment Projects (DOE/GO-102017-4955 - September 2017) Authors Kay Kelly and John Gonzales, National Renewable Energy Laboratory Disclaimer This document is not intended for use as a “how to” guide for individuals or organizations performing a conversion, repower, or retrofit. Instead, it is intended to be used as a guide and resource document for informational purposes only. VEHICLE TECHNOLOGIES OFFICE | cleancities.energy.gov 2 ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, AND REPOWERS Table of Contents Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................................5 -

Morgan Ellis Climate Policy Analyst and Clean Cities Coordinator DNREC [email protected] 302.739.9053

CLEAN TRANSPORTATION IN DELAWARE WILMAPCO’S OUR TOWN CONFERENCE THE PRESENTATION 1) What are alterative fuels? 2) The Fuels 3) What’s Delaware Doing? WHAT ARE ALTERNATIVE FUELED VEHICLES? • “Vehicles that run on a fuel other than traditional petroleum fuels (i.e. gas and diesel)” • Propane • Natural Gas • Electricity • Biodiesel • Ethanol • Hydrogen THERE’S A FUEL FOR EVERY FLEET! DELAWARE’S ALTERNATIVE FUELS • “Vehicles that run on a fuel other than traditional petroleum fuels (i.e. gas and diesel)” • Propane • Natural Gas • Electricity • Biodiesel • Ethanol • Hydrogen THE FUELS PROPANE • By-Product of Natural Gas • Compressed at high pressure to liquefy • Domestic Fuel Source • Great for: • School Busses • Step Vans • Larger Vans • Mid-Sized Vehicles COMPRESSED NATURAL GAS (CNG) • Predominately Methane • Uses existing pipeline distribution system to deliver gas • Good for: • Heavy-Duty Trucks • Passenger cars • School Buses • Waste Management Trucks • DNREC trucks PROPANE AND CNG INFRASTRUCTURE • 8 Propane Autogas Stations • 1 CNG Station • Fleet and Public Access with accounts ELECTRIC VEHICLES • Electricity is considered an alternative fuel • Uses electricity from a power source and stores it in batteries • Two types: • Battery Electric • Plug-in Hybrid • Great for: • Passenger Vehicles EV INFRASTRUCTURE • 61 charging stations in Delaware • At 26 locations • 37,000 Charging Stations in the United States • Three types: • Level 1 • Level 2 • D.C. Fast Charging TYPES OF CHARGING STATIONS Charger Current Type Voltage (V) Charging Primary Use Time Level 1 Alternating 120 V 2 to 5 miles Current (AC) per hour of Residential charge Level 2 AC 240 V 10 to 20 miles Residential per hour of and charge Commercial DC Fast Direct Current 480 V 60 to 80 miles (DC) per 20 min. -

Understanding Long-Term Evolving Patterns of Shared Electric

Experience: Understanding Long-Term Evolving Patterns of Shared Electric Vehicle Networks∗ Guang Wang Xiuyuan Chen Fan Zhang Rutgers University Rutgers University Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced [email protected] [email protected] Technology, CAS [email protected] Yang Wang Desheng Zhang University of Science and Rutgers University Technology of China [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT CCS CONCEPTS Due to the ever-growing concerns on the air pollution and • Networks → Network measurement; Mobile networks; energy security, many cities have started to update their Cyber-physical networks. taxi fleets with electric ones. Although environmentally friendly, the rapid promotion of electric taxis raises prob- KEYWORDS lems to both taxi drivers and governments, e.g., prolonged Electric vehicle; mobility pattern; charging pattern; evolving waiting/charging time, unbalanced utilization of charging experience; shared autonomous vehicle infrastructures and reduced taxi supply due to the long charg- ing time. In this paper, we make the first effort to understand ACM Reference Format: the long-term evolving patterns through a five-year study Guang Wang, Xiuyuan Chen, Fan Zhang, Yang Wang, and Desh- on one of the largest electric taxi networks in the world, i.e., eng Zhang. 2019. Experience: Understanding Long-Term Evolving the Shenzhen electric taxi network in China. In particular, Patterns of Shared Electric Vehicle Networks. In The 25th Annual we perform a comprehensive measurement investigation International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking (Mo- called ePat to explore the evolving mobility and charging biCom ’19), October 21–25, 2019, Los Cabos, Mexico. ACM, New York, patterns of electric vehicles. -

How Practical Are Alternative Fuel Vehicles?

How Practical Are Alternative Fuel Vehicles? Many of us have likely considered an alternative fuel vehicle at some point in our lives. Balancing the positives and negatives is a tricky process and varies greatly based on our personal situations. However, many of the negatives that previously created hesitancy have changed in recent years. Below, we have outlined a few of the most commonly mentioned negatives regarding the two leading alternative fuel vehicle types: Flex Fuel vehicles and Electric/Hybrid vehicles. Then, you can decide for yourself whether one of these vehicle types are practical for you! Cost – How much does the vehicle cost to purchase and operate? Flex Fuel: Flex Fuel vehicles typically cost about the same as a gasoline vehicle.1 For fuel cost, E85 typically costs slightly less than gasoline, however, due to decreased efficiency has a slightly higher cost per mile than gasoline.2 Overall, a Flex Fuel vehicle is likely to be slightly more expensive than a gasoline counterpart. Electric/Hybrid: This situation varies quite a bit depending on where you live. Electric vehicles and hybrid vehicles often cost considerably more than a conventional gasoline vehicle. For example, a plug-in hybrid will cost around $4000-$8000 more than a conventional model.3 However, there are federal rebates and local rebates that can refund thousands of dollars from the purchase price. Electric/Hybrid vehicles also tend to save money on fuel, with the possibility of saving thousands of dollars over the lifetime of the vehicle.4 Whether these rebates and fuel cost savings will eventually account for the higher purchase price can be estimated with comparison tools. -

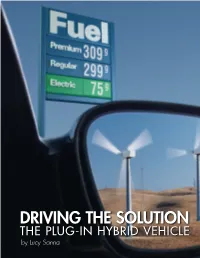

EPRI Journal--Driving the Solution: the Plug-In Hybrid Vehicle

DRIVING THE SOLUTION THE PLUG-IN HYBRID VEHICLE by Lucy Sanna The Story in Brief As automakers gear up to satisfy a growing market for fuel-efficient hybrid electric vehicles, the next- generation hybrid is already cruis- ing city streets, and it can literally run on empty. The plug-in hybrid charges directly from the electricity grid, but unlike its electric vehicle brethren, it sports a liquid fuel tank for unlimited driving range. The technology is here, the electricity infrastructure is in place, and the plug-in hybrid offers a key to replacing foreign oil with domestic resources for energy indepen- dence, reduced CO2 emissions, and lower fuel costs. DRIVING THE SOLUTION THE PLUG-IN HYBRID VEHICLE by Lucy Sanna n November 2005, the first few proto vide a variety of battery options tailored 2004, more than half of which came from Itype plugin hybrid electric vehicles to specific applications—vehicles that can imports. (PHEVs) will roll onto the streets of New run 20, 30, or even more electric miles.” With growing global demand, particu York City, Kansas City, and Los Angeles Until recently, however, even those larly from China and India, the price of a to demonstrate plugin hybrid technology automakers engaged in conventional barrel of oil is climbing at an unprece in varied environments. Like hybrid vehi hybrid technology have been reluctant to dented rate. The added cost and vulnera cles on the market today, the plugin embrace the PHEV, despite growing rec bility of relying on a strategic energy hybrid uses battery power to supplement ognition of the vehicle’s potential. -

The Future of Transportation Alternative Fuel Vehicle Policies in China and United States

Clark University Clark Digital Commons International Development, Community and Master’s Papers Environment (IDCE) 12-2016 The uturF e of Transportation Alternative Fuel Vehicle Policies In China and United States JIyi Lai [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers Part of the Environmental Studies Commons Recommended Citation Lai, JIyi, "The uturF e of Transportation Alternative Fuel Vehicle Policies In China and United States" (2016). International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE). 163. https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers/163 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Master’s Papers at Clark Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE) by an authorized administrator of Clark Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Future of Transportation Alternative Fuel Vehicle Policies In China and United States Jiyi Lai DECEMBER 2016 A Masters Paper Submitted to the faculty of Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the department of IDCE And accepted on the recommendation of ! Christopher Van Atten, Chief Instructor ABSTRACT The Future of Transportation Alternative Fuel Vehicle Policies In China and United States Jiyi Lai The number of passenger cars in use worldwide has been steadily increasing. This has led to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions and other air pollutants, and new efforts to develop alternative fuel vehicles to mitigate reliance on petroleum. Alternative fuel vehicles include a wide range of technologies powered by energy sources other than gasoline or diesel fuel. -

The Road to Zero Next Steps Towards Cleaner Road Transport and Delivering Our Industrial Strategy

The Road to Zero Next steps towards cleaner road transport and delivering our Industrial Strategy July 2018 The Road to Zero Next steps towards cleaner road transport and delivering our Industrial Strategy The Government has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the Government’s website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact the Department. Department for Transport Great Minster House 33 Horseferry Road London SW1P 4DR Telephone 0300 330 3000 General enquiries https://forms.dft.gov.uk Website www.gov.uk/dft © Crown copyright, 2018, except where otherwise stated. Printed in July 2018. Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. You may re-use this information (not including logos or third-party material) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v2.0. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Contents Foreword 1 Policies at a glance 2 Executive Summary 7 Part 1: Drivers of change 21 Part 2: Vehicle Supply and Demand 33 Part 2a: Reducing emissions from vehicles already on our roads 34 Part 2b: Driving uptake of the cleanest new cars and vans 42 Part 2c: -

The Electric Vehicle Evolution

THE ELECTRIC VEHICLE EVOLUTION Electric vehicles are a growing market for new car purchases with more and more people making the switch from the gas station to an electrical outlet to fuel their vehicles. Electric vehicles use electricity as their primary fuel or use electricity along with a conventional engine to improve efficiency (plug-in hybrid vehicles). Drivers are purchasing the vehicles for all kinds of reasons. Many decide to buy when they hear about the savings. Drivers see around $700 in savings a year in gasoline expenses when they drive an average of 12,000 miles. They also can realize substantial tax credits that encourage low-emission and emissions-free driving. Additional benefits include environmental improvements because of reduced vehicle emissions, energy independence by way of using locally-generated electricity and high quality driving performance. With the influx of electric vehicles comes a need for charging infrastructure. Throughout the country, businesses, governments and utilities have been installing electric vehicle charging stations. According to the U.S. Department of Energy’s Alternative Fuels Data Center, there are over tens of thousands of vehicle charging outlets across the country. This trend toward electric vehicles is expected to continue, especially with the billions of dollars that auto manufacturers are investing in these new vehicles. The list of manufacturer support is long with almost every large automobile manufacturer currently developing or selling an electric vehicle. But how and why did this all get started? Let’s step back and take a look at the history of electric transportation. 1 THE ELECTRIC VEHICLE EVOLUTION EARLY SUCCESS Electric vehicles actually have their origin in the 1800s. -

Electric Vehicles: a Primer on Technology and Selected Policy Issues

Electric Vehicles: A Primer on Technology and Selected Policy Issues February 14, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46231 SUMMARY R46231 Electric Vehicles: A Primer on Technology and February 14, 2020 Selected Policy Issues Melissa N. Diaz The market for electrified light-duty vehicles (also called passenger vehicles; including passenger Analyst in Energy Policy cars, pickup trucks, SUVs, and minivans) has grown since the 1990s. During this decade, the first contemporary hybrid-electric vehicle debuted on the global market, followed by the introduction of other types of electric vehicles (EVs). By 2018, electric vehicles made up 4.2% of the 16.9 million new light-duty vehicles sold in the United States that year. Meanwhile, charging infrastructure grew in response to rising electric vehicle ownership, increasing from 3,394 charging stations in 2011 to 78,301 in 2019. However, many locations have sparse or no public charging infrastructure. Electric motors and traction battery packs—most commonly made up of lithium-ion battery cells—set EVs apart from internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs). The battery pack provides power to the motor that drives the vehicle. At times, the motor acts as a generator, sending electricity back to the battery. The broad categories of EVs can be identified by whether they have an internal combustion engine (i.e., hybrid vehicles) and whether the battery pack can be charged by external electricity (i.e., plug-in electric vehicles). The numerous vehicle technologies further determine characteristics such as fuel economy rating, driving range, and greenhouse gas emissions. EVs can be separated into three broad categories: Hybrid-electric vehicles (HEVs): The internal combustion engine primarily powers the wheels. -

Market Conditions for Biogas Vehicles

REPORT Market conditions for biogas vehicles Tomas Rydberg, Mohammed Belhaj, Lisa Bolin, Maria Lindblad, Åke Sjödin, Christina Wolf B1947 April 2010 Report approved: 2010-10-20 John Munthe Scientific director Organization Report Summary IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute Ltd. Project title Market conditions for biogas vehicles Address P.O. Box 5302 SE-400 14 Göteborg Project sponsor Swedish Road Administration Telephone +46 (0)31-725 62 00 Author Tomas Rydberg, Mohammed Belhaj, Lisa Bolin, Maria Lindblad, Åke Sjödin, Christina Wolf Title and subtitle of the report Market conditions for biogas vehicles Summary With a present share of biofuel used in the Swedish road transport sector of 5.2%, the opportunity for reaching the binding target of 10% by 2020 seem promising. It is both likely and desirable that biogas vehicles may make a significant contribution to fulfill Sweden’s obligation under the biofuels directive. It is likely because the stock of biogas (bi-fuel/CNG) vehicles in Sweden is increasing, as is the supply and demand of biogas. It is desirable, because biogas use in the road transport sector has not only climate benefits, but also benefits from an environmental (e.g. improved air quality due to lower emissions of regulated and unregulated air pollutants) and socio-economic (e.g. domestic production, employment) point of view. Keyword biogas, gas-fuelled vehicles, GHG, Bibliographic data IVL Report B1947 The report can be ordered via Homepage: www.ivl.se, e-mail: [email protected], fax+46 (0)8-598 563 90, or via IVL, P.O. Box 21060, SE-100 31 Stockholm Sweden Market conditions for biogas vehicles IVL report B1947 Summary The present report, prepared by the Swedish Environmental Research Institute (IVL) on behalf of the Swedish Road Administration, analyses the market prerequisites for biogas vehicles and biogas used as motor fuel in view of the EU biofuels directive and the Swedish national target to switch to a fossil fuel independent vehicle fleet by before 2030. -

The 'Renewables' Challenge

The ‘Renewables’ Challenge - Biofuels vs. Electric Mobility Hinrich Helms ifeu - Institut für Energie- und Umweltforschung Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Udo Lambrecht ifeu - Institut für Energie- und Umweltforschung Heidelberg, Germany Nils Rettenmaier ifeu - Institut für Energie- und Umweltforschung Heidelberg, Germany Summary Electric vehicles are considered as a key technology for sustainable transport. The use of biofuels in vehicles with con- ventional combustion engines, however, also offers the possibility for a substantial reduction of greenhouse gas emis- sions, without requiring costly batteries and long charging times and without significantly limiting the driving range. A comparison of environmental impacts between both options needs to be based on a life cycle perspective. First screen- ing results presented in this paper show that a diesel car fuelled with RME has considerably lower climate impacts than a comparable battery electric vehicle charged with average German electricity. On the other hand, the use of RME has disadvantages in other impacts categories such as eutrophication. Battery electric vehicles charged with renewable electricity in turn have the best climate impact balance of the considered options and also show among the lowest im- pacts in eutrophication. However, other biofuels such as palm oil and the use of biomass residues offer further reduc- tion potentials, but possibly face limited resources and land use changes. 1. Introduction man Federal Government has therefore set the target of one million electric vehicles in Germany by 2020. Mobility is an important basis for many economic and On the other hand, the use of biofuels in vehicles with private activities and thus a crucial part of our life. -

The Supply Chain for Electric Vehicle Batteries

United States International Trade Commission Journal of International Commerce and Economics December 2018 The Supply Chain for Electric Vehicle Batteries David Coffin and Jeff Horowitz Abstract Electric vehicles (EVs) are a growing part of the passenger vehicle industry due to improved technology, customer interest in reducing carbon footprints, and policy incentives. EV batteries are the key determinant of both the range and cost of the vehicle. This paper explains the importance of EV batteries, describes the structure of the EV battery supply chain, examines current limitations in trade data for EV batteries, and estimates the value added to EV batteries for EVs sold in the United States. Keywords: motor vehicles, cars, passenger vehicles, electric vehicles, vehicle batteries, lithium- ion batteries, supply chain, value chain. Suggested citation: Coffin, David, and Jeff Horowitz. “The Supply Chain for Electric Vehicle Batteries.” Journal of International Commerce and Economics, December 2018. https://www.usitc.gov/journals. This article is the result of the ongoing professional research of USITC staff and is solely meant to represent the opinions and professional research of the authors. It is not meant to represent in any way the views of the U.S. International Trade Commission, any of its individual Commissioners, or the United States Government. Please direct all correspondence to David Coffin and Jeff Horowitz, Office of Industries, U.S. International Trade Commission, 500 E Street SW, Washington, DC 20436, or by email to [email protected] and [email protected]. The Supply Chain for Electric Vehicle Batteries Introduction Supply chains spreading across countries have added complexity to tracking international trade flows and calculating the value each country receives from a particular good.