Frege and the Hierarchy Author(S): Tyler Burge Source: Synthese, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Elementary Set Theory

1 Elementary Set Theory Notation: fg enclose a set. f1; 2; 3g = f3; 2; 2; 1; 3g because a set is not defined by order or multiplicity. f0; 2; 4;:::g = fxjx is an even natural numberg because two ways of writing a set are equivalent. ; is the empty set. x 2 A denotes x is an element of A. N = f0; 1; 2;:::g are the natural numbers. Z = f:::; −2; −1; 0; 1; 2;:::g are the integers. m Q = f n jm; n 2 Z and n 6= 0g are the rational numbers. R are the real numbers. Axiom 1.1. Axiom of Extensionality Let A; B be sets. If (8x)x 2 A iff x 2 B then A = B. Definition 1.1 (Subset). Let A; B be sets. Then A is a subset of B, written A ⊆ B iff (8x) if x 2 A then x 2 B. Theorem 1.1. If A ⊆ B and B ⊆ A then A = B. Proof. Let x be arbitrary. Because A ⊆ B if x 2 A then x 2 B Because B ⊆ A if x 2 B then x 2 A Hence, x 2 A iff x 2 B, thus A = B. Definition 1.2 (Union). Let A; B be sets. The Union A [ B of A and B is defined by x 2 A [ B if x 2 A or x 2 B. Theorem 1.2. A [ (B [ C) = (A [ B) [ C Proof. Let x be arbitrary. x 2 A [ (B [ C) iff x 2 A or x 2 B [ C iff x 2 A or (x 2 B or x 2 C) iff x 2 A or x 2 B or x 2 C iff (x 2 A or x 2 B) or x 2 C iff x 2 A [ B or x 2 C iff x 2 (A [ B) [ C Definition 1.3 (Intersection). -

Conditionals in Political Texts

JOSIP JURAJ STROSSMAYER UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Adnan Bujak Conditionals in political texts A corpus-based study Doctoral dissertation Advisor: Dr. Mario Brdar Osijek, 2014 CONTENTS Abstract ...........................................................................................................................3 List of tables ....................................................................................................................4 List of figures ..................................................................................................................5 List of charts....................................................................................................................6 Abbreviations, Symbols and Font Styles ..........................................................................7 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................9 1.1. The subject matter .........................................................................................9 1.2. Dissertation structure .....................................................................................10 1.3. Rationale .......................................................................................................11 1.4. Research questions ........................................................................................12 2. Theoretical framework .................................................................................................13 -

EVIDENTIALS and RELEVANCE by Ely Ifantidou

EVIDENTIALS AND RELEVANCE by Ely Ifantidou Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London 1994 Department of Phonetics and Linguistics University College London (LONDON ABSTRACT Evidentials are expressions used to indicate the source of evidence and strength of speaker commitment to information conveyed. They include sentence adverbials such as 'obviously', parenthetical constructions such as 'I think', and hearsay expressions such as 'allegedly'. This thesis argues against the speech-act and Gricean accounts of evidentials and defends a Relevance-theoretic account Chapter 1 surveys general linguistic work on evidentials, with particular reference to their semantic and pragmatic status, and raises the following issues: for linguistically encoded evidentials, are they truth-conditional or non-truth-conditional, and do they contribute to explicit or implicit communication? For pragmatically inferred evidentials, is there a pragmatic framework in which they can be adequately accounted for? Chapters 2-4 survey the three main semantic/pragmatic frameworks for the study of evidentials. Chapter 2 argues that speech-act theory fails to give an adequate account of pragmatic inference processes. Chapter 3 argues that while Grice's theory of meaning and communication addresses all the central issues raised in the first chapter, evidentials fall outside Grice's basic categories of meaning and communication. Chapter 4 outlines the assumptions of Relevance Theory that bear on the study of evidentials. I sketch an account of pragmatically inferred evidentials, and introduce three central distinctions: between explicit and implicit communication, truth-conditional and non-truth-conditional meaning, and conceptual and procedural meaning. These distinctions are applied to a variety of linguistically encoded evidentials in chapters 5-7. -

Basics of Social Network Analysis Distribute Or

1 Basics of Social Network Analysis distribute or post, copy, not Do Copyright ©2017 by SAGE Publications, Inc. This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. Chapter 1 Basics of Social Network Analysis 3 Learning Objectives zz Describe basic concepts in social network analysis (SNA) such as nodes, actors, and ties or relations zz Identify different types of social networks, such as directed or undirected, binary or valued, and bipartite or one-mode zz Assess research designs in social network research, and distinguish sampling units, relational forms and contents, and levels of analysis zz Identify network actors at different levels of analysis (e.g., individuals or aggregate units) when reading social network literature zz Describe bipartite networks, know when to use them, and what their advan- tages are zz Explain the three theoretical assumptions that undergird social networkdistribute studies zz Discuss problems of causality in social network analysis, and suggest methods to establish causality in network studies or 1.1 Introduction The term “social network” entered everyday language with the advent of the Internet. As a result, most people will connect the term with the Internet and social media platforms, but it has in fact a much broaderpost, application, as we will see shortly. Still, pictures like Figure 1.1 are what most people will think of when they hear the word “social network”: thousands of points connected to each other. In this particular case, the points represent political blogs in the United States (grey ones are Republican, and dark grey ones are Democrat), the ties indicating hyperlinks between them. -

Formal Construction of a Set Theory in Coq

Saarland University Faculty of Natural Sciences and Technology I Department of Computer Science Masters Thesis Formal Construction of a Set Theory in Coq submitted by Jonas Kaiser on November 23, 2012 Supervisor Prof. Dr. Gert Smolka Advisor Dr. Chad E. Brown Reviewers Prof. Dr. Gert Smolka Dr. Chad E. Brown Eidesstattliche Erklarung¨ Ich erklare¨ hiermit an Eides Statt, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbststandig¨ verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel verwendet habe. Statement in Lieu of an Oath I hereby confirm that I have written this thesis on my own and that I have not used any other media or materials than the ones referred to in this thesis. Einverstandniserkl¨ arung¨ Ich bin damit einverstanden, dass meine (bestandene) Arbeit in beiden Versionen in die Bibliothek der Informatik aufgenommen und damit vero¨ffentlicht wird. Declaration of Consent I agree to make both versions of my thesis (with a passing grade) accessible to the public by having them added to the library of the Computer Science Department. Saarbrucken,¨ (Datum/Date) (Unterschrift/Signature) iii Acknowledgements First of all I would like to express my sincerest gratitude towards my advisor, Chad Brown, who supported me throughout this work. His extensive knowledge and insights opened my eyes to the beauty of axiomatic set theory and foundational mathematics. We spent many hours discussing the minute details of the various constructions and he taught me the importance of mathematical rigour. Equally important was the support of my supervisor, Prof. Smolka, who first introduced me to the topic and was there whenever a question arose. -

English Knowledge Base Category Hierarchy

J English Knowledge Base Category Hierarchy This document provides a list of all the concepts in the knowledge base that serve as categories. This document divided into six sections, corresponding to the six main branches of the knowledge base: ■ Branch 1: science and technology ■ Branch 2: business and economics ■ Branch 3: government and military ■ Branch 4: social environment ■ Branch 5: geography ■ Branch 6: abstract ideas and concepts The categories are presented in an inverted-tree hierarchy and within each category, sub-categories are listed in alphabetical order. Note: This document does not contain all the concepts found in the knowledge base. It only contains those concepts that serve as categories (meaning they are parent nodes in the hierarchy). English Knowledge Base Category Hierarchy J-1 Branch 1: science and technology Branch 1: science and technology [1] communications [2] journalism [3] broadcast journalism [3] photojournalism [3] print journalism [4] newspapers [2] public speaking [2] publishing industry [3] desktop publishing [3] periodicals [4] business publications [3] printing [2] telecommunications industry [3] computer networking [4] Internet technology [5] Internet providers [5] Web browsers [5] search engines [3] data transmission [3] fiber optics [3] telephone service [1] formal education [2] colleges and universities [3] academic degrees [3] business education [2] curricula and methods [2] library science [2] reference books [2] schools [2] teachers and students [1] hard sciences [2] aerospace industry [3] -

Mechanistic Hierarchy Realism and Function Perspectivalism

1 Mechanistic Hierarchy Realism and Function Perspectivalism Abstract Mechanistic explanation involves the attribution of functions to both mechanisms and their component parts, and function attribution plays a central role in the individuation of mechanisms. Our aim in this paper is to investigate the impact of a perspectival view of function attribution for the broader mechanist project, and specifically for realism about mechanistic hierarchies. We argue that, contrary to the claims of function perspectivalists such as Craver, one cannot endorse both function perspectivalism and mechanistic hierarchy realism: if functions are perspectival, then so are the levels of a mechanistic hierarchy. We illustrate this argument with an example from recent neuroscience, where the mechanism responsible for the phenomenon of ephaptic coupling cross-cuts (in a hierarchical sense) the more familiar mechanism for synaptic firing. Finally, we consider what kind of structure there is left to be realist about for the function perspectivalist. 1. Introduction Mechanistic explanation has emerged as the dominant account of explanation across much of philosophy of science, especially for cognitive neuroscience, biology, and chemistry. This account suggests that to explain a phenomenon is to offer a mechanism that produces it. Crucially, for many mechanists, mechanisms differ from models and other idealized, counterfactual, or instrumental constructs of science, in that mechanisms are actual parts of the world. Models, diagrams, simulations, or other descriptions may represent a mechanism, but the mechanism itself comprises a real structure, independent of our aims and interests, and this real structure plays an explanatory role (either constitutively, for ontic mechanists, or 2 by reference, for epistemic mechanists – we will return to this point later). -

European Journal of Educational Research Volume 9, Issue 1, 395- 411

Research Article doi: 10.12973/eu-jer.9.1.395 European Journal of Educational Research Volume 9, Issue 1, 395- 411. ISSN: 2165-8714 http://www.eu-jer.com/ ‘Sentence Crimes’: Blurring the Boundaries between the Sentence-Level Accuracies and their Meanings Conveyed Yohannes Telaumbanua* Nurmalina Yalmiadi Masrul Politeknik Negeri Padang, Universitas Pahlawan Tuanku Universitas Dharma Andalas Universitas Pahlawan Tuanku INDONESIA Tambusai Pekanbaru Riau Padang, INDONESIA Tambusai, INDONESIA Indonesia, INDONESIA Received: September 9, 2019▪ Revised: October 29, 2019 ▪ Accepted: January 15, 2020 Abstract: The syntactic complexities of English sentence structures induced the Indonesian students’ sentence-level accuracies blurred. Reciprocally, the meanings conveyed are left hanging. The readers are increasingly at sixes and sevens. The Sentence Crimes were, therefore, the major essences of diagnosing the students’ sentence-level inaccuracies in this study. This study aimed at diagnosing the 2nd-year PNP ED students’ SCs as the writers of English Paragraph Writing at the Writing II course. Qualitatively, both observation and documentation were the instruments of collecting the data while the 1984 Miles & Huberman’s Model and the 1973 Corder’s Clinical Elicitation were employed to analyse the data as regards the SCs produced by the students. The findings designated that the major sources of the students’ SCs were the subordinating/dependent clauses (noun, adverb, and relative clauses), that-clauses, participle phrases, infinitive phrases, lonely verb phrases, an afterthought, appositive fragments, fused sentences, and comma splices. As a result, the SCs/fragments flopped to communicate complete thoughts because they were grammatically incorrect; lacked a subject, a verb; the independent clauses ran together without properly using punctuation marks, conjunctions or transitions; and two or more independent clauses were purely joined by commas but failed to consider using conjunctions. -

Exclusivity, Teleology and Hierarchy: Our Aristotelean Legacy

Know!. Org. 26(1999)No.2 65 H.A. Olson: Exclusivity, Teleology and Hierarchy: Our Aristotelean Legacy Exclusivity, Teleology and Hierarchy: Our Aristotelean Legacy Hope A. Olson School of Library & Information Studies, University of Alberta Hope A. Olson is an Associate Professor and Graduate Coordinator in the School of Library and Information Studies at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. She holds a PhD from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and MLS from the University of Toronto. Her re search is generally in the area of subject access to information with a focus on classification. She approaches this work using feminist, poststructural and postcolonial theory. Dr. Olson teaches organization of knowledge, cataloguing and classification, and courses examining issues in femi nism and in globalization and diversity as they relate to library and information studies. Olson, H.A. (1999). Exclusivity, Teleology and Hierarchy: Our Aristotelean Legacy. Knowl· edge Organization, 26(2). 65-73. 16 refs. ABSTRACT: This paper examines Parmenides's Fragments, Plato's The Sophist, and Aristotle's Prior AnalyticsJ Parts ofAnimals and Generation ofAnimals to identify three underlying presumptions of classical logic using the method of Foucauldian discourse analysis. These three presumptions are the notion of mutually exclusive categories, teleology in the sense of linear progression toward a goal, and hierarchy both through logical division and through the dominance of some classes over others. These three presumptions are linked to classificatory thought in the western tradition. The purpose of making these connections is to investi gate the cultural specificity to western culture of widespread classificatory practice. It is a step in a larger study to examine classi fication as a cultural construction that may be systemically incompatible with other cultures and with marginalized elements of western culture. -

The Problem of Social Class Under Socialism Author(S): Sharon Zukin Source: Theory and Society, Vol

The Problem of Social Class under Socialism Author(s): Sharon Zukin Source: Theory and Society, Vol. 6, No. 3 (Nov., 1978), pp. 391-427 Published by: Springer Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/656759 Accessed: 24-06-2015 21:55 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/656759?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Theory and Society. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 132.236.27.111 on Wed, 24 Jun 2015 21:55:45 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 391 THE PROBLEM OF SOCIAL CLASS UNDER SOCIALISM SHARON ZUKIN Posing the problem of social class under socialismimplies that the concept of class can be removed from the historical context of capitalist society and applied to societies which either do not know or do not claim to know the classicalcapitalist mode of production. Overthe past fifty years, the obstacles to such an analysis have often led to political recriminationsand termino- logical culs-de-sac. -

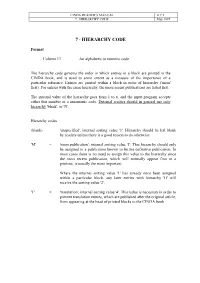

7.1 7 : HIERARCHY CODE May 1997

CINDA READER’S MANUAL II.7.1 7 : HIERARCHY CODE May 1997 7 - HIERARCHY CODE Format Column 17 An alphabetic or numeric code. The hierarchy code governs the order in which entries in a block are printed in the CINDA book, and is used to some extent as a measure of the importance of a particular reference. Entries are printed within a block in order of hierarchy ('main' first). For entries with the same hierarchy, the more recent publications are listed first. The internal value of the hierarchy goes from 1 to 6, and the input program accepts either this number or a mnemonic code. External readers should in general use only hierarchy 'blank', or 'N'. Hierarchy codes (blank) 'unspecified', internal sorting value '3'. Hierarchy should be left blank by readers unless there is a good reason to do otherwise 'M' = 'main publication', internal sorting value '1'. This hierarchy should only be assigned to a publication known to be the definitive publication. In most cases there is no need to assign this value to the hierarchy since the most recent publication, which will normally appear first in a printout, is usually the most important. Where the internal sorting value '1' has already once been assigned within a particular block, any later entries with hierarchy 'H' will receive the sorting value '2'. 'T' = 'translation', internal sorting value '4'. This value is necessary in order to prevent translation entries, which are published after the original article, from appearing at the head of printed blocks in the CINDA book. CINDA READER’S MANUAL II.7.2 7 : HIERARCHY CODE May 1997 Hierarchy codes (cont/d) 'N' = 'No Book Flag'. -

Frege and the Logic of Sense and Reference

FREGE AND THE LOGIC OF SENSE AND REFERENCE Kevin C. Klement Routledge New York & London Published in 2002 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2002 by Kevin C. Klement All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infomration storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Klement, Kevin C., 1974– Frege and the logic of sense and reference / by Kevin Klement. p. cm — (Studies in philosophy) Includes bibliographical references and index ISBN 0-415-93790-6 1. Frege, Gottlob, 1848–1925. 2. Sense (Philosophy) 3. Reference (Philosophy) I. Title II. Studies in philosophy (New York, N. Y.) B3245.F24 K54 2001 12'.68'092—dc21 2001048169 Contents Page Preface ix Abbreviations xiii 1. The Need for a Logical Calculus for the Theory of Sinn and Bedeutung 3 Introduction 3 Frege’s Project: Logicism and the Notion of Begriffsschrift 4 The Theory of Sinn and Bedeutung 8 The Limitations of the Begriffsschrift 14 Filling the Gap 21 2. The Logic of the Grundgesetze 25 Logical Language and the Content of Logic 25 Functionality and Predication 28 Quantifiers and Gothic Letters 32 Roman Letters: An Alternative Notation for Generality 38 Value-Ranges and Extensions of Concepts 42 The Syntactic Rules of the Begriffsschrift 44 The Axiomatization of Frege’s System 49 Responses to the Paradox 56 v vi Contents 3.