Exclusivity, Teleology and Hierarchy: Our Aristotelean Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Example of Sharing Information Expressed with Vague Terms

Talking about Forests: an Example of Sharing Information Expressed with Vague Terms Luc´ıa Gomez´ Alvarez´ a, Brandon Bennett a and Adam Richard-Bollans a a University of Leeds, The United Kingdom Abstract. Most natural language terms do not have precise universally agreed defi- nitions that fix their meanings. Even when conversation participants share the same vocabulary and agree on taxonomic relationships (such as subsumption and mutual exclusivity, which might be encoded in an ontology), they may differ greatly in the specific semantics they give to the terms. We illustrate this with the example of ‘forest’, for which the problematic arising of the assignation of different meanings is repeatedly reported in the literature. This is especially the case in the context of an unprecedented scale of publicly available geographic data, where information and databases, even when tagged to ontologies, may present a substantial semantic variation, which challenges interoperability and knowledge exchange. Our research addresses the issue of conceptual vagueness in ontology by pro- viding a framework based on supervaluation semantics that explicitly represents the semantic variability of a concept as a set of admissible precise interpretations. Moreover, we describe the tools that support the conceptual negotiation between an agent and the system, and the specification and reasoning within standpoints. Keywords. concept negotiation, supervaluation, standpoint, forest, GIS, vagueness 1. Introduction Since the shift in philosophy of language from logical positivism to behaviourism and pragmatism, it is widely accepted that most natural language terms do not have precise universally agreed definitions that fix their meanings. Even when conversation partici- pants share the same vocabulary and agree on taxonomic relationships (such as subsump- tion and mutual exclusivity, which might be encoded in an ontology), they may differ greatly in the specific semantics they give to the terms in a particular situation. -

Jonah N. Schupbach: Curriculum Vitae

Jonah N. Schupbach Department of Philosophy, University of Utah [email protected] 402 CTIHB, 215 S. Central Campus Drive jonahschupbach.com Salt Lake City, Utah 84112 (801) 585-5810 Areas of Specialization Areas of Competence Epistemology (including Formal Epistemology) Philosophy of Religion Logic Metaphysics Philosophy of Science Philosophy of Cognitive Science Appointments University of Utah Associate Professor (tenure granted 2017), Department of Philosophy, 2017–present. Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, 2011–2017. Tilburg University Visiting Fellow, Tilburg Center for Logic & Philosophy of Science (TiLPS), September 2008– June 2009. Education Ph.D. History & Philosophy of Science, University of Pittsburgh, 2011. Dissertation: Studies in the Logic of Explanatory Power (defended June 14, 2011). Co-directors: John Earman (Pittsburgh, HPS), Edouard Machery (Pittsburgh, HPS). M.A. Philosophy, Western Michigan University, 2006. M.A. Philosophy of Religion, Denver Seminary, 2004. B.S.E. Industrial Engineering, University of Iowa, 2001. Jonah N. Schupbach,Curriculum Vitae 2 Publications Books Conjunctive Explanations: The Nature, Epistemology, and Psychology of Explanatory Multiplicity. New York: Routledge (to appear in Routledge’s Studies in the Philosophy of Science series). Co-edited with David H. Glass. Bayesianism and Scientific Reasoning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (to appear in Cambridge’s Elements in the Philosophy of Science series). Book Chapters “William Paley,” in Stewart Goetz and Charles Taliaferro (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Philosophy of Religion. Malden, MA: Wiley (forthcoming). “Inference to the Best Explanation, Cleaned Up and Made Respectable,” in Kevin McCain and Ted Poston (eds.), Best Explanations: New Essays on Inference to the Best Explanation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, (2017): 39-61. -

The Epistemic Value of 'Κατά Τόν Λόγον': Meteorology

The epistemic value of ‘κατά τόν λόγον’: Meteorology 1.7 By Eleftheria Rotsia Dimou Submitted to Central European University Department of Philosophy In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the one year MA degree of Philosophy Supervisor: Associate Professor István Bodnár Budapest, Hungary 2018 CEU eTD Collection © Copyright by Eleftheria Rotsia Dimou, 2018 1 Τὸν μὲν οὖν Ἀναξαγόραν φασὶν ἀποκρίνασθαι πρός τινα διαποροῦντα τοιαῦτ ̓ ἄττα καὶ διερωτῶντα τίνος ἕνεκ ̓ ἄν τις ἕλοιτο γενέσθαι μᾶλλον ἢ μὴ γενέσθαι ‘τοῦ’ φάναι “θεωρῆσαι τὸν οὐρανὸν καὶ τὴν περὶ τὸν ὅλον κόσμον τάξιν”. (Aristotle, E.E Ι, 1216a12–14). CEU eTD Collection 2 Contents 1. Abstract ……………………………………………………….……4 2. Acknowledgments……………………………………..……………5 3. Introduction……………………………………………..…………..6 4. Part I: An Ontological Question…………………………...……….9 5. Part II: An Epistemological Question……………………………..14 6. Concluding Remarks…………………………………………..…..38 7. Bibliography………………………………………………………40 CEU eTD Collection 3 Abstract Ι will attempt to shed some light on the troubling matter of the obscure particulars ― treated by Aristotle in Meteorology ― (τῶν ἀφανῶν τῇ αἰσθήσει), that is, phenomena which are not apparent to the senses in their full extent (Meteorology 344a5). In the framework of the present paper, the aim is to highlight the use of κατά τόν λόγον which appears in the first lines of chapter I.7 of Aristotle’s Meteorology, by focusing on two philosophical questions: one ontological (what is the ontological status of obscure phenomena?) and one epistemological (can we come to the knowledge of such phenomena, and if so, in which way?). Aristotle proposes two answers to these questions in the text, respectively: The meteora (and therefore the comets discussed in chapter I.7 of Meteorology) are natural entities. -

Between Foundation and Convention

NCCU Philosophical Journal Vol.10 (July 2003), pp.35-74 ©Department of Philosophy, National Chengchi University Between Foundation and Convention: Carnap’s Evolution between Schlick and Neurath in the Vienna Circle Jeu-Jenq Yuann Tunghai University Abstract For long the foundationalist image of logical positivism has been considered a matter of course. And it is basically accepted that R. Carnap has a great deal to do with this traditional image. Recent researches reveal that this image is not entirely true; Carnap can be deemed as a conventionalist also when some key conceptions are understood from a different point of view. Indeed, by examining some Carnap’s works, we are urged to realize that his view of science is somehow situated somewhere between foundationalism and conventionalism. We argue in this paper that Carnap’s weaving situation can be comprehended by taking into account the discussions taking place in the Vienna Circle and notably the debates among R. 36 NCCU Philosopical Journal Vol.10 Carnap, M. Schlick, and O. Neurath. We intend to make it explicit that Carnap’s stance was first in line with that of Schlick’s foundationalism and then moved to a more conventionalist one under the influence of Neurath. By this argument, we intend to demonstrate the following two points: 1) Discussions in the Vienna Circle were far from unanimous; 2) Carnap’s stance containing ‘an ethical attitude of tolerance’ proceeded mainly under Neurath’s influence. Key Words: Foundationalism, Conventionalism, R. Carnap, M. Schlick, O. Neurath * Received April 06, 2003; accepted July 16, 2003 Proofreaders: Bing-Jie Li Between Foundation and Convention 37 1. -

Basics of Social Network Analysis Distribute Or

1 Basics of Social Network Analysis distribute or post, copy, not Do Copyright ©2017 by SAGE Publications, Inc. This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. Chapter 1 Basics of Social Network Analysis 3 Learning Objectives zz Describe basic concepts in social network analysis (SNA) such as nodes, actors, and ties or relations zz Identify different types of social networks, such as directed or undirected, binary or valued, and bipartite or one-mode zz Assess research designs in social network research, and distinguish sampling units, relational forms and contents, and levels of analysis zz Identify network actors at different levels of analysis (e.g., individuals or aggregate units) when reading social network literature zz Describe bipartite networks, know when to use them, and what their advan- tages are zz Explain the three theoretical assumptions that undergird social networkdistribute studies zz Discuss problems of causality in social network analysis, and suggest methods to establish causality in network studies or 1.1 Introduction The term “social network” entered everyday language with the advent of the Internet. As a result, most people will connect the term with the Internet and social media platforms, but it has in fact a much broaderpost, application, as we will see shortly. Still, pictures like Figure 1.1 are what most people will think of when they hear the word “social network”: thousands of points connected to each other. In this particular case, the points represent political blogs in the United States (grey ones are Republican, and dark grey ones are Democrat), the ties indicating hyperlinks between them. -

English Knowledge Base Category Hierarchy

J English Knowledge Base Category Hierarchy This document provides a list of all the concepts in the knowledge base that serve as categories. This document divided into six sections, corresponding to the six main branches of the knowledge base: ■ Branch 1: science and technology ■ Branch 2: business and economics ■ Branch 3: government and military ■ Branch 4: social environment ■ Branch 5: geography ■ Branch 6: abstract ideas and concepts The categories are presented in an inverted-tree hierarchy and within each category, sub-categories are listed in alphabetical order. Note: This document does not contain all the concepts found in the knowledge base. It only contains those concepts that serve as categories (meaning they are parent nodes in the hierarchy). English Knowledge Base Category Hierarchy J-1 Branch 1: science and technology Branch 1: science and technology [1] communications [2] journalism [3] broadcast journalism [3] photojournalism [3] print journalism [4] newspapers [2] public speaking [2] publishing industry [3] desktop publishing [3] periodicals [4] business publications [3] printing [2] telecommunications industry [3] computer networking [4] Internet technology [5] Internet providers [5] Web browsers [5] search engines [3] data transmission [3] fiber optics [3] telephone service [1] formal education [2] colleges and universities [3] academic degrees [3] business education [2] curricula and methods [2] library science [2] reference books [2] schools [2] teachers and students [1] hard sciences [2] aerospace industry [3] -

Consciousness, the Unconscious and Mathematical Modeling of Thinking

entropy Article On “Decisions and Revisions Which a Minute Will Reverse”: Consciousness, The Unconscious and Mathematical Modeling of Thinking Arkady Plotnitsky Literature, Theory and Cultural Studies Program, Philosophy and Literature Program, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA; [email protected] Abstract: This article considers a partly philosophical question: What are the ontological and epistemological reasons for using quantum-like models or theories (models and theories based on the mathematical formalism of quantum theory) vs. classical-like ones (based on the mathematics of classical physics), in considering human thinking and decision making? This question is only partly philosophical because it also concerns the scientific understanding of the phenomena considered by the theories that use mathematical models of either type, just as in physics itself, where this question also arises as a physical question. This is because this question is in effect: What are the physical reasons for using, even if not requiring, these types of theories in considering quantum phenomena, which these theories predict fully in accord with the experiment? This is clearly also a physical, rather than only philosophical, question and so is, accordingly, the question of whether one needs classical-like or quantum-like theories or both (just as in physics we use both classical and quantum theories) in considering human thinking in psychology and related fields, such as decision Citation: Plotnitsky, A. On science. It comes as no surprise that many of these reasons are parallel to those that are responsible “Decisions and Revisions Which a for the use of QM and QFT in the case of quantum phenomena. -

Mechanistic Hierarchy Realism and Function Perspectivalism

1 Mechanistic Hierarchy Realism and Function Perspectivalism Abstract Mechanistic explanation involves the attribution of functions to both mechanisms and their component parts, and function attribution plays a central role in the individuation of mechanisms. Our aim in this paper is to investigate the impact of a perspectival view of function attribution for the broader mechanist project, and specifically for realism about mechanistic hierarchies. We argue that, contrary to the claims of function perspectivalists such as Craver, one cannot endorse both function perspectivalism and mechanistic hierarchy realism: if functions are perspectival, then so are the levels of a mechanistic hierarchy. We illustrate this argument with an example from recent neuroscience, where the mechanism responsible for the phenomenon of ephaptic coupling cross-cuts (in a hierarchical sense) the more familiar mechanism for synaptic firing. Finally, we consider what kind of structure there is left to be realist about for the function perspectivalist. 1. Introduction Mechanistic explanation has emerged as the dominant account of explanation across much of philosophy of science, especially for cognitive neuroscience, biology, and chemistry. This account suggests that to explain a phenomenon is to offer a mechanism that produces it. Crucially, for many mechanists, mechanisms differ from models and other idealized, counterfactual, or instrumental constructs of science, in that mechanisms are actual parts of the world. Models, diagrams, simulations, or other descriptions may represent a mechanism, but the mechanism itself comprises a real structure, independent of our aims and interests, and this real structure plays an explanatory role (either constitutively, for ontic mechanists, or 2 by reference, for epistemic mechanists – we will return to this point later). -

Catalogue of Titles of Works Attributed to Aristotle

Catalogue of Titles of works attributed by Aristotle 1 To enhance readability of the translations and usability of the catalogues, I have inserted the following bold headings into the lists. These have no authority in any manuscript, but are based on a theory about the composition of the lists described in chapter 3. The text and numbering follows that of O. Gigon, Librorum deperditorum fragmenta. PART ONE: Titles in Diogenes Laertius (D) I. Universal works (ta kathalou) A. The treatises (ta syntagmatika) 1. The dialogues or exoterica (ta dialogika ex terika) 2. The works in propria persona or lectures (ta autopros pa akroamatika) a. Instrumental works (ta organika) b. Practical works (ta praktika) c. Productive Works (ta poi tika) d. Theoretical works (ta the r tika) . Natural philosophy (ta physiologia) . Mathematics (ta math matika) B. Notebooks (ta hypomn matika) II. Intermediate works (ta metaxu) III. Particular works (ta merika) PART TWO: Titles in the Vita Hesychii (H) This list is organized in the same way as D, with two exceptions. First, IA2c “productive works” has dropped out. Second, there is an appendix, organized as follows: IV. Appendix A. Intermediate or Particular works B. Treatises C. Notebooks D. Falsely ascribed works PART THREE: Titles in Ptolemy al-Garib (A) This list is organized in the same way as D, except it contains none of the Intermediate or Particular works. It was written in Arabic, and later translated into Latin, and then reconstructed into Greek, which I here translate. PART FOUR: Titles in the order of Bekker (B) The modern edition contains works only in IA2 (“the works in propria persona”), and replaces the theoretical works before the practical and productive, as follows. -

In Press at Cognition. This File Is a Pre-Print and May Contain Errors Or Omissions Not Present in the Final Published Version

In press at Cognition. This file is a pre-print and may contain errors or omissions not present in the final published version. Linguistic Conventionality and the Role of Epistemic Reasoning in Children’s Mutual Exclusivity Inferences Mahesh Srinivasan,1 Ruthe Foushee,1 Andrew Bartnof,1 & David Barner2 1University of California, Berkeley 2University of California, San Diego Please address correspondence to: Mahesh Srinivasan Department of Psychology University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-1650 Phone: 650-823-9488 Email: [email protected] Mutual Exclusivity and Conventionality Abstract To interpret an interlocutor’s use of a novel word (e.g., “give me the papaya”), children typically exclude referents that they already have labels for (like an “apple”), and expect the word to refer to something they do not have a label for (like the papaya). The goal of the present studies was to test whether such mutual exclusivity inferences require children to reason about the words their interlocutors know and could have chosen to say: e.g., If she had wanted the “apple” she would have asked for it (since she knows the word “apple”), so she must want the papaya. Across four studies, we document that both children and adults will make mutual exclusivity inferences even when they believe that their interlocutor does not share their knowledge of relevant, alternative words, suggesting that such inferences do not require reasoning about an interlocutor’s epistemic states. Instead, our findings suggest that children’s own knowledge of an object’s label, together with their belief that this is the conventional label for the object in their language, and that this convention applies to their interlocutor, is sufficient to support their mutual exclusivity inferences. -

The Problem of Social Class Under Socialism Author(S): Sharon Zukin Source: Theory and Society, Vol

The Problem of Social Class under Socialism Author(s): Sharon Zukin Source: Theory and Society, Vol. 6, No. 3 (Nov., 1978), pp. 391-427 Published by: Springer Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/656759 Accessed: 24-06-2015 21:55 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/656759?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Theory and Society. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 132.236.27.111 on Wed, 24 Jun 2015 21:55:45 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 391 THE PROBLEM OF SOCIAL CLASS UNDER SOCIALISM SHARON ZUKIN Posing the problem of social class under socialismimplies that the concept of class can be removed from the historical context of capitalist society and applied to societies which either do not know or do not claim to know the classicalcapitalist mode of production. Overthe past fifty years, the obstacles to such an analysis have often led to political recriminationsand termino- logical culs-de-sac. -

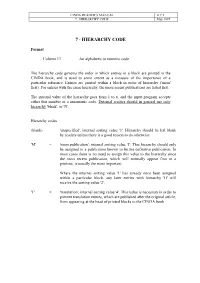

7.1 7 : HIERARCHY CODE May 1997

CINDA READER’S MANUAL II.7.1 7 : HIERARCHY CODE May 1997 7 - HIERARCHY CODE Format Column 17 An alphabetic or numeric code. The hierarchy code governs the order in which entries in a block are printed in the CINDA book, and is used to some extent as a measure of the importance of a particular reference. Entries are printed within a block in order of hierarchy ('main' first). For entries with the same hierarchy, the more recent publications are listed first. The internal value of the hierarchy goes from 1 to 6, and the input program accepts either this number or a mnemonic code. External readers should in general use only hierarchy 'blank', or 'N'. Hierarchy codes (blank) 'unspecified', internal sorting value '3'. Hierarchy should be left blank by readers unless there is a good reason to do otherwise 'M' = 'main publication', internal sorting value '1'. This hierarchy should only be assigned to a publication known to be the definitive publication. In most cases there is no need to assign this value to the hierarchy since the most recent publication, which will normally appear first in a printout, is usually the most important. Where the internal sorting value '1' has already once been assigned within a particular block, any later entries with hierarchy 'H' will receive the sorting value '2'. 'T' = 'translation', internal sorting value '4'. This value is necessary in order to prevent translation entries, which are published after the original article, from appearing at the head of printed blocks in the CINDA book. CINDA READER’S MANUAL II.7.2 7 : HIERARCHY CODE May 1997 Hierarchy codes (cont/d) 'N' = 'No Book Flag'.