Town of Bethlehem Final Draft Comprehensive Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UW-River Falls Student and Professor Team up to Conduct Research on Turtles

SPORTS, PAGE 6 NEWS, PAGE 3 ETCETERA, PAGE 8 Athlete of the Week: River Falls Public Library offers variety of ‘The Girl on the Train’ Trenton Monson free resources fails to live up to advertised hype University of Wisconsin River Falls TUDENT OICE OctoberS 14, 2016 www.uwrfvoice.com V Volume 103, Issue 4 Student’s innovation helps paraplegic horseback riders Tori Schneider Falcon News Service When UW-River Falls senior Shanna Bur- ris, an equine management major, got accept- ed into the McNair Scholars Program, she knew she wanted to help paraplegic horse- back riders. Her first step was to survey paraplegic rid- ers to find out what they needed the most. Then she created a hoist that can lift a saddle onto a horse. Other obstacles paraplegic riders may face when getting ready to ride a horse are already taken care of with wheelchair ramps and lifts to place them on the animals. However, with- out Burris’ hoist, these riders need someone else to maneuver the saddles for them. “Knowing this population and knowing some of the struggles that they go through try- ing to tack up their own horse and how benefi- cial riding is to them, I wanted to figure out a way to make it more accessible and help them be more independent,” Burris said. Burris is a non-traditional student. She has worked in health care for many years and was inspired by the many lifts used to move pa- tients. Her research and the hoist were presented at a symposium at the University of Califor- nia-Berkeley this past summer. -

The Chronicle

The Chronicle 76th Year, No. 38 Duke University, Durham, North Carolina Tuesday, October 21, 1980 Carter, Reagan to debate before election Format approved By Terence Smith apparently had expected. Roast "We offered to meet them < 1»80 NYT News Service beef and turkey sandwiches anytime, anyplace." he said, WASHINGTON — Negotiators were brought in as the talks "but they clearly are not for President Carter and Ronald dragged on through the interested in allowing George Reagan agreed Monday on a afternoon. Bush to debate Vice President format for a presidential debate, Using the 1976 debates Mondale." Later Moe speculated but failed in more than four between Carter and Gerald R. that the Reagan camp was hours of discussions to settle on Ford as a model, the two sides concerned that such a debate a mutually acceptable place and agreed that the candidates would tend to emphasize "the date. would be questioned by a panel differences on the issues" Both sides, however, of newsmen. Time will be between the Republican predicted that the remaining provided for rebuttal by each of candidate and his running differences would be resolved the candidates and follow-up mate. and that the two candidates questions from the reporters. Baker contended, however, Annamaria's 'Bat' would meet in a nationally Despite public suggestions that it was more a problem of televised encounter before from Carter that he would favor scheduling. "We can't afford to Nov. 4. a more free-wheeling debate in take Bush off the campaign dead at 58 which the candidates could trial for several days while "We offered them any date question each other directly, Governor Reagan isoff as well." By Jordan Feiger place. -

Brown, Reagan Slide to California Victories Nuclear Initiative Loses Two to One; Tunney Crushes Hayden by Anne Burke New York City

University of California at Santa Barbara Wednesday, June 9, 1976 Brown, Reagan Slide to California Victories Nuclear Initiative Loses Two to One; Tunney Crushes Hayden By Anne Burke New York City. Governor Jerry Brown and former Carter pulled a runaway victory in governor Ronald Reagan won expected Ohio winning 119 delegates and 52 landslide victories in yesterday’s percent of the vote. Udall scored his California primary, endangering both ninth seconcFplace finish in Ohio with 20 GOP frontrunner Gerald Ford’s and delegates and 2 percent. Democratic leader Jimmy Carter’s In Ohio Ford won with 55 percent to guarantees for a first ballot nomination at Reagan’s 45 percent. Ford got 88 this summer’s conventions. delegates to Reagan’s 9. Carter, however, picked up 218 An uncommitted slate of 75 delegates delegates in yesterday’s final primaries, in 'New Jersey, leaning heavily in favor of despite a California crush and a New Brown and Hubert Humphrey, took the Jersey upset. Arizona Congressman New Jersey Democratic race. Carter Morris Udall, placing second against picked up only 25 delegates, but won the ■ B h r a i Carter in the Democratic delegate count, popular vote. Humphrey earlier said that THE WINNERS-Governor Jerry Brown and former Governor Ronald Reagan score pulled out o f the race early in the he might enter the race if Carter came out big victories in yesterday’s California primary. evening, calling Carter the “likely with less than 1250 delegates after Democratic nominee” and throwing his today’s primaries. support to “party unity.” Wallace Wins in Runaway; Brown claimed 202 delegates and 59 On the Republican side in New Jersey, percent over Carter’s 68 delegates with 20 Ford running unopposed, won all of the percent. -

Vera Sidhwa - Poems

Poetry Series Vera Sidhwa - poems - Publication Date: 2016 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Vera Sidhwa() www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 A Bear Oh teddy, I cuddle you, I look for the softness in you. My cuddling makes you soft, On my sofa cushion. I sit with you on my lap. Oh bear, I meet you in the forest. I see all your huge fur, And large, sharp teeth, In your big mouth. And I run the other way. Vera Sidhwa www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 2 A Bird A Bird It was in my brain. It was in my veins. It just took off and then, Flew it's own way in and out. The trees rocked in the wind. All nature seemed in, A fury and crazy. The bird flew away. This was a real bird you see. It was in and out of me. I looked at in glee. It was the bird of perfection. I knew it would bring news to me. For this I could really see, That all ideas have wings of their own. And this idea did too. Vera Sidhwa www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 3 A Chiming Bell A Chiming Bell A chiming bell resounded through, The daisies and flowers of this field. A chime heard by the flowers, Was their ever wanting need. You see, their field was silent, And the flowers needed a sound. The chiming bell knew this, So it chimed about and around. Through the loud fields now, The flowers began to listen. -

HAPPINESS Copy.Pages

QUOTES ON HAPPINESS I asked professors who teach the meaning of life to tell me what is happiness. And I went to famous executives who boss the work of thousands of men. They all shook their heads and gave me a smile as though I was trying to fool with them. And then one Sunday afternoon I wandered out along the DesPlaines River And I saw a crowd of Hungarians under the trees with their women and children and a keg of beer and an accordion. --Carl Sandburg Choose your life’s mate carefully. From this one decision will come 90 percent of all your happiness or misery. —H. Jackson Brown, Jr. Three grand essentials to happiness in this life are something to do, something to love, and something to hope for. --Joseph Addison I am 100% responsible for my own happiness. It is a state of mind cultivated by my choices and habits, not by things or people. Yes, my children make me happy. Yes, sitting at the beach and watching a sunset makes me happy. But I don’t ever want to make the mistake of thinking my happiness is dependent on something—a different job, more money, another child, wood floors, a remodeled bathroom. --Kelle Hampton We have no more right to consume happiness without producing it than to consume wealth without producing it. --George Bernard Shaw There is no psychiatrist in the world like a puppy licking your face. —Ben Williams - 1! - The happy people are those who are producing something; the bored people are those who are consuming much and producing nothing. -

RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 1300-1599

RCA Discography Part 5 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 1300-1599 LPM 1300 – Thursday’s Child – Eartha Kitt [1956] Fascinating Man/Mademoiselle Kitt/Oggere/No Importa Si Menti/Lisbon Antigua/Just An Old Fashioned Girl/Le Danseur De Charleston/Lazy Afternoon/Jonny/If I Can't Take It With Me/Thursday's Child/Lullaby Of Birdland LPM 1301 – Rhythm Was His Business – George Williams [1957] I Wanna Hear Swing Songs/For Dancers Only/Lunceford Special/I'll Take The South/Margie/Yard Dog Mazurka/Rhythm Is Our Business/Swingin' On C/Uptown Blues/White Heat/'Tain't Whatcha Do/Harlem Express LPM 1302 – A Mellow Bit of Rhythm – Andy Kirk and His Clouds of Joy [1956] A Mellow Bit Of Rhythm/Little Joe From Chicago/McGhee Special/Hey Lawdy Mama/Cloudy/Froggy Bottom/Wednesday Night Hop/Walkin' And Swingin'/Scratchin' In The Gravel/Toadie Toddle/Take It And Git/Boogie Woogie Cocktail LPM 1303 – My Guitar – Renato Rossini [1956] Torna A Surriento/Pescatore A Pusilleco/Guapparia/Tarantella/Scalinatelia/Mandolinata/Sciumo(The River)/O'ciucciariello (Little Donkey)/Mattinata/Passione/Papere/Finesta Che Luceva/Musetta's Walts/O'marenariello (I Have But One Heart)/A' Vela/Dicitencello Vuie (Just Say You Love Her) LPM 1304 – One Night in Monte Carlo – Guy Lupar [1956] There's Danger In Your Eyes/Mam'selle/Bistro/The Blue Riviera (Sur Les Bonds De La Riviera)/It All Began With You/If You Love Me (Hymna A L'amour)/My Lost Melody (Je N'en Connais Pas La Fin)/The Gallant Tango/Two -

Journeys an Anthology of Adult Student Writing 2011

Journeys An Anthology of Adult Student Writing 2011 Chau Yang, Saint Paul Mission The mission of the Minnesota Literacy Council is to share the power of learning through education, community building, and advocacy. Through this mission, MLC: • Helps adults become self-sufficient citizens through improved literacy. • Helps at-risk children and families gain literacy skills to increase school success. • Strengthens communities by raising literacy levels and encouraging volunteerism. • Raises awareness of literacy needs and services throughout the state. Acknowledgements The Minnesota Literacy Council extends our heartfelt thanks to Elizabeth Bance, Stephen Burgdorf, Katharine Engdahl and Sara Sparrowgrove who have donated their time and talent to the planning, design, editing, and production of this book. Special thanks also to MLC staff Guy Haglund, Allison Runchey, Melissa Martinson and Cathy Grady for helping make Journeys a success. Fi- nally, we are deeply grateful for the generous donation of $500 from Todd and Mimi Burke through the Burke Family Fund in memory of Todd’s late mother. The Minnesota Literacy Council www.theMLC.org 651-645-2277 Hotline: 800-222-1990 700 Raymond Avenue, Suite 180 Saint Paul, Minnesota 55114-1404 © 2011 Minnesota Literacy Council, Saint Paul, Minnesota, USA. ISBN 13: 978-0-9844923-1-2 ISBN 10: 0-9844923-1-3 ii Table of Contents Introduction iv I Am… 1 My Family 23 Traditions and Customs 47 Memories of Home 56 For Those I Love 75 Poetry and Prose 87 Struggles and Decisions 109 Learning and Lessons 130 Hopes and Dreams 154 Index of Authors and Artists 170 Cover Art by Abdir Ahman Samatar, Rochester • Back Cover Art by Vue Xiong,Saint Paul iii Introduction Dear Reader, The following pages are filled with stories by Minnesotans whose voices are rarely heard. -

Cascadia Don't Fall Apart John Lewis Englehardt University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2014 Cascadia Don't Fall Apart John Lewis Englehardt University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Englehardt, John Lewis, "Cascadia Don't Fall Apart" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 2325. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2325 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Cascadia Don’t Fall Apart Cascadia Don’t Fall Apart A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing by John Englehardt Seattle University Bachelor of Arts in English/Creative Writing, 2009 May 2014 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. Professor Rilla Askew Thesis Director Professor Timothy O’Grady Professor Michael Heffernan Committee Member Committee Member ABSTRACT This short story collection explores the tenuousness of relationships—both romantic and familial—against the backdrop of Washington State’s regional identity. These stories feature tsunami debris washing up on the peninsula, a biologist combating wetland violations in Olympia, a funerary artist in Seattle, young lovers attempting to be sexually explorative, a young man so befuddled by college graduation that he joins the infantry, and an adult son attempting to comfort his sick father. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. -

Of Audiotape

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. CLARK TERRY NEA Jazz Master (1991) Interviewee: Clark Terry (December 14, 1920 – February 21, 2015) Interviewer: William Brower Date: June 15 and 22, 1999 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 150 pp. Transcriber’s note: Evidently there was no recording engineer available for the Clark Terry interview, and the interviewer, William Brower, handled the record process by himself. He had some technical problems. In the interview of June 15, 1999, one of the two channels is shorted out and emits nothing but a buzz, disrupting the entire session; this problem is exacerbated, affecting both channels, in the last two hours of this session. Brower acknowledges these problems at the beginning of the interview that took place one week later, on June 22, 1999. This later session has an excellent stereophonic sound. Terry: Saw a fellow sitting there, standing on a rock. He was driving around the corner, in the middle of the block. Is that close enough? Brower: Okay. We’re going to try this again. This is Bill Brower, talking with Mr. Clark Terry on June 15th for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Project, and we were getting background on the Terry family, and I’m going to ask if you would, to repeat the things that you told me about your parents’ background. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 Terry: My mother’s name was Mary Scott. -

Be Happy Interior Sample 2.Indd 1 1/19/09 8:52:53 PM Also by Robert Holden, Ph.D

be happy Copyright 2009 HAY HOUSE. DO NOT use without permission from HAY HOUSE. Be Happy Interior sample 2.indd 1 1/19/09 8:52:53 PM also by robert holden, Ph.d. ••••• books Success Intelligence* Happiness NOW!* Balancing Work & Life (with Ben Renshaw) Shift Happens! Every Day is a Gift (with Marika Borg (Burton)) ••••• cd programs Be Happy* Happiness NOW!* Success Intelligence* ••••• flip calendar Happiness NOW!* Success NOW!* (available August 2009) *Available from Hay House Copyright 2009 HAY HOUSE. DO NOT use without permission from HAY HOUSE. Be Happy Interior sample 2.indd 2 1/19/09 8:52:53 PM be happy release the power of happiness in YOU Robert Holden, Ph.D. HAY hoUse, InC. Carlsbad, California • new york City london • sydney • Johannesburg Vancouver • hong Kong • new delhi Copyright 2009 HAY HOUSE. DO NOT use without permission from HAY HOUSE. Be Happy Interior sample 2.indd 3 1/19/09 8:52:54 PM Copyright © 2009 by Robert Holden Published and distributed in the United States by: Hay House, Inc.: www.hayhouse.com • Published and distributed in Australia by: Hay House Australia Pty. Ltd.: www.hayhouse. com.au • Published and distributed in the Republic of South Africa by: Hay House SA (Pty), Ltd.: www.hayhouse.co.za • Distributed in Canada by: Raincoast: www.raincoast. com • Published in India by: Hay House Publishers India: www.hayhouse.co.in Design: Jenny Richards Indexer: Richard Comfort All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any mechanical, photographic, or electronic process, or in the form of a phonographic recording; nor may it be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, or otherwise be copied for public or private use—other than for “fair use” as brief quotations embodied in articles and reviews— without prior written permission of the publisher. -

Discovery of Happiness

DISCOVERY OF HAPPINESS BY A B MEHTA DISCOVERY OF HAPPINESS CONTENTS Preface A UNIVERSAL DESIRE ................................................................................................. 7 What is Happiness? ......................................................................................................... 8 PERCEPTIONS OF HAPPINESS ................................................................................ 12 It is unique for each....................................................................................................... 12 Changing Perception with age ...................................................................................... 13 As a Child.................................................................................................................. 13 As a Teenager............................................................................................................ 17 As an Adult ............................................................................................................... 19 As a Senior Citizen ................................................................................................... 20 SCIENTIFIC APPRECIATION ................................................................................... 23 Evolution through ages ................................................................................................. 23 Role of Brain‘s Chemistry ............................................................................................ 26 The "Happiness Equation" -

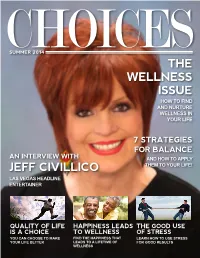

The Wellness Issue Jeff Civillico

CHOICESSUMMER 2014 THE WELLNESS ISSUE HOW TO FIND AND NURTURE WELLNESS IN YOUR LIFE 7 STRATEGIES FOR BALANCE AN INTERVIEW WITH AND HOW TO APPLY JEFF CIVILLICO THEM TO YOUR LIFE! LAS VEGAS HEADLINE ENTERTAINER QUALITY OF LIFE HAPPINESS LEADS THE GOOD USE IS A CHOICE TO WELLNESS OF STRESS YOU CAN CHOOSE TO MAKE FIND THE HAPPINESS THAT LEARN HOW TO USE STRESS YOUR LIFE BETTER LEADS TO A LIFETIME OF FOR GOOD RESULTS WELLNESS CONTENTS FINDING WELLNESS 18 WHAT REMAINS WHEN YOU LEAVE? BY JACK W. ROLFE 20 SAVING MY SANITY - TAKING CARE OF ME BY BECKY GRAVA DAVIS 33 WHEN LIFE IS HANGING IN THE BALANCE BY KATHY HAMILTON CHOOSE WELLNESS 10 LIVING A MORE CELEBRITY INTERVIEW REWARDING LIFE BY ALISA WEIS JEFF CIVILLICO 27 BY JUDI MOREO CHOOSE TO CHOOSE 14 BY LAUREN MCLAUGHLIN LIFESTYLE 23 7 STRATEGIES FOR BALANCE QUALITY OF LIFE IS A BY JAN MILLS 04 CHOICE BY JUDI MOREO 36 NEVER SAY LOSE WEIGHT BY PAULA HUFFMAN UNDERSTAND BALANCE 08 BY PAM BURKE TYLER THE GOOD USE OF STRESS 42 BY KRISTINE MODZELEWSKI M.S. A MINDFUL APPROACH 16 BY PETER SHANKLAND 44 HAPPINESS PROVIDES WELLNESS MAKING TIME FOR THE BY JOAN PECK 38 FIVE PILLARS BY JOAN BURGE 48 THE VALUE OF PRIORITIES BY JENNIFER TARLIN SEMRAD 50 COMMUNICATING WITH 5 REASONS FOR KEEPING YOUR FAMILY 52 BY DEBORAH CLARK COCONUT OIL IN THE BATHROOM A FINAL NOTE BY JASMINE FREEMAN 54 BY JUDI MOREO FROM THE EDITOR Is there such a thing as life balance? It is definitely challenging to keep up with the demands of work and home life without getting stressed out.