Nbilograpi Bibliographic Data Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secondary Tillage Implements

SECONDARY TILLAGE Tillage operations following primary tillage which are performed to create proper soil tilth for seeding and planting are secondary tillage. These are lighter and finer operations, performed on the soil after primary tillage operations. Secondary tillage consists of conditioning the soil to meet the different tillage objectives of the farm. These operations consume less power per unit area compared to primary tillage operations. Secondary tillage implements may be tractor drawn or bullock drawn implements. 1. Harrow Harrow is a secondary tillage implement that cuts the soil to a shallow depth for smoothening and pulverizing the soil as well as to cut the weeds and to mix the materials with the soil. There are several types of harrow used in India such as disc harrow, spike tooth harrow, spring tooth harrow, acme harrow, patela, triangular harrow, bade harrow, guntaka and reciprocating power harrow. 1.1. Disc harrow It is a harrow, which performs the harrowing operation by means of a set, or a number of sets of rotating slat discs, each set being mounted on a common shaft. Disc harrow is found very suitable for hard ground, full of stalks and grasses. It cuts the lumps of soil, clods and roots. Disc are mounted on one, two or more axles which may be set at a variable angle to the line of motion. As the harrow is pulled ahead, the discs rotate on the ground. Depending upon the disc arrangements, disc harrows are divided into two classes a) Single action and b) Double action. Single action disc harrow It is a harrow with two gangs placed end to end, which throw the soil in opposite directions. -

The Guide to Good Black Grass Stale Seedbeds

The Guide To Good Black Grass Stale Seedbeds An essential checklist to maximise the agronomic benefits FOREWORD Independent Soil Advisor by Philip Wright www.wrightresolutions.co.uk/id2 Stale Seedbeds : The importance of soil structure The soil on your farm is your most important asset, providing the foundation for yield and profit. Yield losses attributable to compaction range from 15% to 50% or greater. These losses can be the difference between profit and loss for many crops, so avoiding and correcting compaction is key. Maintaining good soil structure is vital; key indicators of good soil structure include: Porosity - to allow easy passage of roots, plus for good air and water storage or movement; Stable aggregates - to cope with heavy rain, and to resist breakdown or loss by erosion; Good biology - having adequate levels of organic matter, aerobic conditions and ‘soil life’ including good earthworm numbers; 2 THE GUIDE TO GOOD BLACK GRASS STALE SEEDBEDS Above left : Above right : Well aggregated structure. Compact low-porosity soil with a wet layer holding water. Drainability - capable of a fast return from saturation to field capacity after high rainfall; Good crops - high yielding crops develop large root systems which maintain good structure. COURTESY OF LEMKEN UK / AGRII 3 Compaction is best spotted when soils are moist to wet. Digging holes will show layers resisting moisture movement, and checking root growth through the profile will show if remediation is needed. Long term, building roots and organic matter levels through the profile will give a sustainable structure. Removing barriers to water and root movement will allow nature to work most efficiently to provide this. -

A Study of Agricultural Implements

A STUDY OF AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS .BY... NORMAN CHARLES WOODIN THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN MECHANICAL ENGINEERING IN THE COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESENTED JUNE, 1904 CONTENTS. HISTORY. 1. Walking Plows. 2. Sulky and Gang Plows. 3. Harrows. 4. Grain Drills. 5. Corn Planters & check-rowers. 6. Corn Cultivators. STUDY 1. Plows. (1) Technical Terms. (2) Classification. (3) Sue tion and Land. (4) Line of Draft. (5) Tempering. (6) Classification of Goods of a Plow Manufactory. (7) Walking Plows. (1) General Purpose Plows. (2) Stubble Plows. (8) Riding Plow's. (9) Disc Plow's. (10) Curves of Plows and Profile machine. 2. Harrows. (1) Spike Tooth Harrow (2) Disc Harrows. 3. Corn Planters and Check- Rowers. 4. Cultivators. 1. A STUDY OF AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS. INTRODUCTORY. There are today five distinct classes of agricultural implements. Sometimes six classes are given. They are as follows: (1) Implements for clearing the ground, break ing it and otherwise preparing it for the reception of the seed. (2) Implements for depositing the seed. (3) Implements for the cultivation of the plant. (4) Implements for gathering the crops. (5) Implements for preparing the crops for market. (6) Miscellaneous implements applied to var ious farm uses. The first, second and third classes are manufactured in one factory and form one industry, while the fourth and fifth classes each form separate industries. These are kept separate and very seldom are they seen to intermingle. It is the first class of business, comprising the first second and third classes of implements to which this thesis is devoted. -

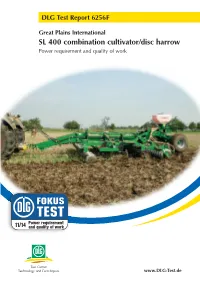

SL 400 Combination Cultivator/Disc Harrow Power Requirement and Quality of Work

DLG Test Report 6256 F Great Plains International SL 400 combination cultivator/disc harrow Power requirement and quality of work Test Center Technology and Farm Inputs www.DLG-Test.de Overview The FokusTest is a smallerscale The DLG – actual working depth and DLG usability test intended to FokusTest “Power cul tivation horizon of the tools; allow product differentiation and requirement and – profile of the soil surface before special highlighting of innova quality of work” and after the working step; tions in machinery and technical was carried out with the GREAT products used primarily in agri PLAINS DTX 300 mounted short – crumbling of the soil culture, forestry, horticulture, disc harrow with deep loosening (aggregate size distribution); fruit cultivation and viticulture, as tines (working width: 300 cm – compactness after the well as in landscape and munici (118 in.)). The measurements were working step; pal management. taken on harvested, largely flat – straw covering and straw areas of wheat cultivation at the incorporation; This test focuses on testing a DLG International Crop Production product’s individual qualitative Center in BernburgStrenzfeld – operation. criteria, e.g. fatigue strength, per (SaxonyAnhalt). formance, or quality of work. In addition, the tractor’s fuel con The DLG FokusTest “Power sumption was measured. The scope of testing can include requirement and quality of work” In order to document the field criteria from the testing frame examined the following testing conditions during soil cultivation, work of a DLG SignumTest, the para meters based on the DLG the stubble heights, straw yield and DLG’s extensive usability test testing framework for soil cultiva ground moisture were determined for technical products, and con tion equipment: and described. -

Keeping It All in the Mix! Cultivation REVOLVES Around Them – Catros, Certos and Ceus!

Keeping it all in the mix! Cultivation REVOLVES around them – Catros, Certos and Ceus! Catros compact disc harrow+ 12003-2TS The Catros compact disc harrow is the ideal machine for quick, shallow and intensive stubble culti- vation in working widths from 2.5 m to 12 m. The Certos heavy compact disc harrow is perfect for medium-deep, intensively-mixed soil tillage and for applications where there are large amounts of crop residues. With the Ceus disc & tine combination cultivator, the front discs, which provide the shallow-mix- ing, is combined with a following tine element for top soil deep loosening. Kit that has a job to do almost the whole year round Winter: Spring: Maintenance-free Incorporation of break in the winter catch crops and liquid thanks to its manure/seedbed life-long disc bearing preparation for spring lubrication crops Summer: Early stale seedbed preparation and second- Autumn: ary stubble cultivation/ Seedbed preparation incorporation of liquid combined with manure/combination of base fertilisation soil tillage with catch application crop sowing The three common strengths ∅ ∅ 1 Sprung rubber buffer mountings The elastic sprung rubber buffer blocks for suspend- ing the discs, not only ensure optimum contour fol- lowing, but also act as overload safety protection on each individual disc. The oversized rubber buffers are maintenance-free and are characterised by a large spring deflection providing peace of mind even where there are large stones about. ∅ 2 Individual disc suspension Individual disc suspension for optimised contour fol- lowing and excellent throughput complete with built-in overload protection and stone release. ∅ 2-row angular contact ball bearing 2 x seal ring (O-Ring) 2 x cast rings with face seal ∅ Face seal built into conical seats Gear oil filled housing Proven 1,000,000 times over! ∅ 3 Maintenance-free face seal No lubrication ever again – thanks to the maintenance-free disc bearings With no need to lubricate the disc bearings, this results in significantly reduced overall down times. -

Soil-Tool-Residue Interactions: Measurements and Modelling

Soil-Tool-Residue Interactions: Measurements and Modelling by Zhiwei Zeng A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Biosystems Engineering University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2019 by Zhiwei Zeng Abstract Soil-tool-residue interactions are at the centre of many agricultural field operations. The study of soil-tool-residue interactions is one of the fundamental aspects of soil dynamics in agricultural engineering. The aim of this study was to investigate dynamic behaviours of soil-tool-residue interactions including soil cutting forces, soil displacement, soil loosening and furrow profile, straw displacement, residue cover and incorporation. Experimental studies of soil-tool-residue interactions were conducted for various soil-engaging tools (fluted coulter, rippled disc, and compact disc harrow) working on several field conditions (corn stubble, wheat stubble, and bare soil) at different operational parameters (working speed and depth). Numerical models of the soil-tool-residue interactions were developed for a micropenetrometer, a subsoiler, and a sweep using the discrete element method (DEM). The models were calibrated and validated by comparing simulation results with experimental data from soil bin and field tests. Field testing results of vertical tillage tools demonstrated that fluted coulters left less surface residue, incorporated more residue into the soil, created a wider furrow, and disturbed a larger area than rippled discs. The effect of working speed was more dominant than the coulter geometry on the tillage performance of the fluted coulters. Soil bin tests of a compact disc harrow indicated that disc spacing and offset had significant effects on soil disturbance characteristics, and the effects varied with the tillage depth. -

Mechanical Weed Control in Arable Crops

MECHANICAL WEED CONTROL IN ARABLE CROPS OPTIMISING AND PROMOTING MECHANICAL WEED CONTROL CASDAR PROJECT 2009/2011. TEXT VERSION: MARCH 2012. ► ► ► ► — ► ► ► ► ► ► ► ► ► — ► ► - ► ► -— ► ► - ► ► — ► ► ► ► - ► - ► ► - — – — -- - -— TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE (PG. 5) MECHANICAL WEED CONTROL: GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS (PG. 7) PREVENTIVE MEASURES FOR CONTROLLING WEEDS (PG. 9) MECHANICALLY MANAGING WEEDS DURING THE CROP SEASON (PG. 15) A FARMER'S EXPERIENCE (PG. 22) DESCRIPTIVE SHEET 1: MECHANICAL WEED CONTROL IN COMMON WHEAT (AND WINTER GRAINS) (PG. 27) DESCRIPTIVE SHEET 2: MECHANICAL WEED CONTROL IN FABA BEAN (PG. 39) DESCRIPTIVE SHEET 3: MECHANICAL WEED CONTROL IN LINSEED (PG. 47) DESCRIPTIVE SHEET 4: MECHANICAL WEED CONTROL IN MAIZE (PG. 53) DESCRIPTIVE SHEET 5: MECHANICAL WEED CONTROL IN SPRING BARLEY (PG. 61) DESCRIPTIVE SHEET 6: MECHANICAL WEED CONTROL IN SOYBEAN (PG. 67) DESCRIPTIVE SHEET 7: MECHANICAL WEED CONTROL IN SUNFLOWER (PG. -

Estimating the Energy Requirements and Some of Technical Properties for Someof Seed Bed Preparation Equipment

IOSR Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science (IOSR-JAVS) e-ISSN: 2319-2380, p-ISSN: 2319-2372. Volume 10, Issue 10 Ver. III (October 2017), PP 36-42 www.iosrjournals.org Estimating the Energy Requirements and some of Technical properties for someof seed bed Preparation Equipment. Abdulrazak A. Jasim¹Faiz F. Majeed² Laith A. AL- Hashimy ³ ¹ Professor Doctor, Dept. of Agricultural Machines and Equipment, College of Agriculture, Univ. of Baghdad, ² Lecturer, Dept. of Agricultural Machines and Equipment, College of Agriculture, Univ. of Baghdad, ³ Lecturer, Dept. of Agricultural Machines and Equipment, College of Agriculture, Univ. of Baghdad, Corresponding Author: Laith A. AL- Hashimy Abstract: BACKGROUND: The presence of farm tractor, and his active rule to operates most of farm equipment in the second half of the nineteenth century made it the main source of power in the farm, many developments on tractors had led to the improvement and variation of their power sources. The multiplicity and diversity of soil types, crops, agricultural process and climatic conditions due to different countries or regions led to found different collections of seed bed preparation equipment each one has different function. OBJECTIVE: To estimating and evaluating the energy requirements and some technical indicators of some seed bed preparation equipment with New Holland tractor. RESULTS: Land plane showed a superiority comparing with disc ridger and ditcher in recording higher practical productivity, lowest fuel consumption, lowestmachinery unitenergy requirement, and the lowest treatment practical depth. CONCLUSION: Land plane with rotary harrow and the chiselplow achieved the highest practical productivity, lowest treatment practical depth, and the lowest energy requirement. -

Computer Aided Adaptive System Design with Engineering Systematics and Manufacturing

Advances in Science and Technology Research Journal Volume 11, Issue 4, December 2017, pages 83–96 Research Article DOI: 10.12913/22998624/77069 COMPUTER AIDED ADAPTIVE SYSTEM DESIGN WITH ENGINEERING SYSTEMATICS AND MANUFACTURING Gurkan Irsel1 1 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Trakya University, Edirne 22100, Turkey e-mail: [email protected] Received: 2017.09.18 ABSTRACT Accepted: 2017.11.01 This research practically discusses and presents the stages of design process in prod- Published: 2017.12.05 uct development. Design process was realized through CATIA. The product devel- oped is an agricultural device called as “disc harrow”. Therefore, agricultural details are presented together with machine design. A roller system is added to disc harrow in this study. Thus; the current system and the additional roller system are discussed with the principles of methodological construction and design objectives are defined. Both the current system and the additional roller system are designed in parallel with these objectives. Structural stress analysis is performed at different kinetic positions of the disc harrow connection of the roller system. System design is achieved by considering the feedback from such analyses and design objectives. The hereby design is obtained. The additional roller system is mounted and field survey is carried out. Contribution of the roller to disc harrow process, defined design objectives, ratio of the realization of design objectives and results of stress analyses are evaluated. Keywords: CATIA, structural analysis, shape design, adaptive structure, product de- velopment, disc harrow INTRODUCTION low this traditional agricultural operation equip- ment to perform in a more efficient manner. Today’s modern agriculture industry requires Utilization of combined and modular systems a wide variety of equipment and special machine is an effect solution for sustainable agriculture. -

Drills and Cultivators Drills ’N’ Hoes

With cost pressures“ and herbicide resistance increasing, conventional growers are showing an interest in inter-row kit.” LAMMA preview Drills and cultivators Drills ’n’ hoes From direct fertiliser drills to Väderstad available on the 12 and 18 row Tempo L interrow hoes, there was a After launching on the market in November, models and is based on the same high Väderstad will be showcasing its new Carrier capacity Fenix III metering system as the huge array of cultivation kit XL 425-625 cultivator –– fitted with the 5000-litre hopper, delivering up to 350kg/ha launched at last month’s CrossCutter Disc –– at the NEC next month. fertiliser at 15km/h planting speed, says Designed for conserving moisture in the the firm. Agritechnica. But what’s seedbed, the cultivator has the ability to relevant to the UK market? work at ultra-shallow depths of only 3cm, as Pöttinger well as down to 5cm, across the full working Though visitors won’t be able to see it in the And what can farmers expect width of the machine. According to flesh at LAMMA, the Terrasem Fertiliser Pro to see on display at next Väderstad, this enables efficient mixing mulch seed drill (with direct fertilisation) is of crop residues within the topsoil and the next big thing from Pöttinger. month’s LAMMA event? encourages an early weed chit. One of the real selling points of this piece CPM finds out more. “A shallow stale seedbed increases of kit is that the simultaneous use of tool the number of seeds germinating, and combinations (for example, front board with By Charlotte Cunningham encourages earlier emergence,” says UK tillage discs) in combination with applying marketing manager, Andy Gamble. -

Effects of Working Depth and Wheel Slip on Fuel Consumption of Selected Tillage Implements

182 March, 2014 Agric Eng Int: CIGR Journal Open access at http://www.cigrjournal.org Vol. 16, No.1 Effects of working depth and wheel slip on fuel consumption of selected tillage implements G. Moitzi1*, H. Wagentristl2, K. Refenner2, H. Weingartmann1, G. Piringer1, J. Boxberger1, A. Gronauer1 (1. University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU); Department of Sustainable Agricultural Systems; Division of Agricultural Engineering, Peter Jordan-Strasse 82; A-1190 Vienna; 2. University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU); Department of Crop Science; Experimental Farm Gross Enzersdorf, Schlosshoferstraße 31; A-2301 Gross Enzersdorf Abstract: Rising fossil fuel prices are leading to an increasing awareness of energy efficiency in plant production. Tillage in particular can consume large amounts of fuel. For four tillage implements (reversible mouldboard plough, short disc harrow, universal-cultivator, subsoiler), this study quantifies the effect of different working depths on fuel consumption, wheel slip, field capacity and specific energy consumption. A four-wheel drive tractor (92 kW) was equipped with a data-acquisition system for engine speed, vehicle speed, wheel speed and fuel consumption. Fuel consumption was measured in the fuel system with an integrated high-precision flow-meter. The results show that the area-specific fuel consumption increased linearly with working depth for both the mouldboard plough and the short disc harrow, but disproportionately for the subsoiler. Wheel slip was found to increase fuel consumption and decrease field capacity performance at all depths. The influence of the engine speed was shown in a separate experiment with a universal-cultivator. Increasing the engine speed from 1,513 r min-1 to 2,042 r min-1 results in an increase of 80% for the fuel consumption rate (L/h) and 35% for the area-specific fuel consumption (L/ha). -

Weeds Have Been the Problem Since the Agriculture Came Into Existence

Title of Course Organic Farming Class B. Sc. Ag , Third Year Topic Weed Management in Organic Farming College College of Agriculture , Jabalpur By Dr Amit Kumar Jha INTRODUCTION rice (Oryza sativa), Chulai(Amaranthus spp), Gullidanda (Phalaris minor), Bhang Weeds have been the problem since (Cannabis sativa), mexican poppy the agriculture came into existence as these (Argemone mexicana), Hiran Khuri compete with the crop of interest for various (Convolvulus arvensis) etc. Some of them resources and also act as hosts for different are allergic and noxious such as P diseases and insects. Losses in Indian hysterophorus (congress/carrot grass), agriculture due to weeds account for 33 per Cirsium arvense (Canada thistle), cent. Among the different weeds some of the Stinking nettle (Bichhu Buti) etc. The important ones are: congress grass ubiquitous presence of such plants is (Parthenium hysterophorus), wild oat responsible for health problems from skin (Avena fatua), Dudhi (Euphorbia spp), Bathu allergies to breathing trouble and sinusitis (Chenopodium album), Phoolakri (Lantana injurious to livingorganisms (Jose and Saini camara), Doob (Cynodon dactylon), 2015). For the weed management motha (Cyprus rotundus),wild conventionally chemical herbicides are being used. The herbicides are very Cultural practices effective for weed control but they prove to be detrimental in various ways for Crop rotation: The weeds such as P example some of them have residual minor, A fatua etc which are associated effects, some make the soil sick, some with the specific crops can be controlled by cause air pollution thereby respiratory or means of crop rotation. These weeds can skin problems, some cause water be managed in wheat field by growing pea, pollution and some of them are harmful to gramorpotato in rotation.