We MUST Talk About the Discourse the Changing European Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf Dokument

Udskriftsdato: 2. oktober 2021 2017/1 BTB 91 (Gældende) Betænkning over Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om en uvildig undersøgelse af udlændinge og integrationsministerens håndtering af adskilt indkvartering af mindreårige gifte eller samlevende asylansøgere Ministerium: Folketinget Betænkning afgivet af Udvalget for Forretningsordenen den 23. maj 2018 Betænkning over Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om en uvildig undersøgelse af udlændinge- og integrationsministerens håndtering af adskilt indkvartering af mindreårige gifte eller samlevende asylansøgere [af Mattias Tesfaye (S), Nikolaj Villumsen (EL), Josephine Fock (ALT), Sofie Carsten Nielsen (RV) og Holger K. Nielsen (SF)] 1. Udvalgsarbejdet Beslutningsforslaget blev fremsat den 14. marts 2018 og var til 1. behandling den 26. april 2018. Be- slutningsforslaget blev efter 1. behandling henvist til behandling i Udvalget for Forretningsordenen. Møder Udvalget har behandlet beslutningsforslaget i 2 møder. 2. Indstillinger og politiske bemærkninger Et flertal i udvalget (DF, V, LA og KF) indstiller beslutningsforslaget til forkastelse. Flertallet konstaterer, at sagen om udlændinge- og integrationsministerens håndtering af adskilt ind- kvartering af mindreårige gifte eller samlevende asylansøgere er blevet diskuteret i mange, lange samråd, og at sagen derfor er belyst. Flertallet konstaterer samtidig, at ministeren flere gange har redegjort for forløbet. Det er sket både skriftligt og mundtligt. Flertallet konstaterer også, at den kritik, som Folketingets Ombudsmand rettede mod forløbet i 2017, er en kritik, som udlændinge- og integrationsministeren har taget til efterretning. Det gælder både kritikken af selve ordlyden i pressemeddelelsen og kritikken af, at pressemeddelelsen medførte en risiko for forkerte afgørelser. Flertallet mener, at det afgørende har været, at der blev lagt en så restriktiv linje som muligt. For flertallet ønsker at beskytte pigerne bedst muligt, og flertallet ønsker at bekæmpe skikken med barnebru- de. -

ABUSING the LEGACY of the HOLOCAUST: the ROLE of Ngos in EXPLOITING HUMAN RIGHTS to DEMONIZE ISRAEL Gerald M

ABUSING THE LEGACY OF THE HOLOCAUST: THE ROLE OF NGOs IN EXPLOITING HUMAN RIGHTS TO DEMONIZE ISRAEL Gerald M. Steinberg In the wake of the Holocaust, as human rights norms have come to the fore, NGOs have become major actors in international politics in general and in the Arab-Israeli conflict in particular. These organizations and their leaders form an extremely powerful “NGO community” that has propelled the anti-Israeli agenda in international frameworks such as the UN Human Rights Commission and the 2001 UN Conference against Racism in Durban. Through their reports, press releases, and influence among academics and diplomats, these NGOs propagated false charges of “massacre” during the Israeli army’s antiterror operation in Jenin (Defensive Shield) and misrepresent Israel’s separation barrier as an “apartheid wall.” This community has exploited the “halo effect” of human rights rhetoric to promote highly particularistic goals. In most cases small groups of individuals, with substantial funds obtained from non- profit foundations and governments (particularly European), use the NGO frameworks to gain influence and pursue private political agendas, without being accountable to any system of checks and balances. Jewish Political Studies Review 16:3-4 (Fall 2004) 59 60 Gerald M. Steinberg This process has been most salient in the framework of the Arab-Israeli conflict. The ideology of anticolonialism (the precursor to today’s antiglobalization) and political correctness is dominant in the NGO community. This ideology accepted the post-1967 pro-Palestinian narrative and images of victimization, while labeling Israel as a neocolo- nialist aggressor. Thus, behind the human rights rhetoric, these NGOs are at the forefront of demonizing Israel and of the new anti-Semitism that seeks to deny the Jewish people sovereign equality. -

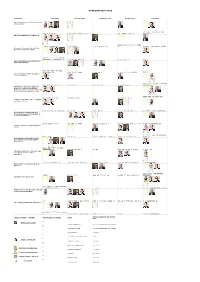

Kandidattest Fv15

KANDIDATTEST FV15 SPØRGSMÅL HELT UENIG DELVIST UENIG HVERKEN/ELLER DELVIST ENIG HELT ENIG Efter folkeskolereformen får eleverne for lange skoledage CCCC IIIIII KKKKKKKKKK OOO AAA B F O VVVVVV AAAAA BBB C FFFFF O VV O B C I OOOO V ØØ ÅÅ ØØØØØØØ Å Afgiften på cigaretter skal sættes op AAAAA B CC F KKK O V ØØØØ C IIIIII K OOOOO VV F I O VVVVV A B C KK O V ØØ Å AA BBB CC FFFF KKKK O ØØØ ÅÅ Et besøg hos den praktiserende læge skal koste eksempelvis 100 kr. AAAAAAA CCCC FFFFFF KKKKKK OOOOOOOO V ØØØØØØØØØ ÅÅ A BB C KKK OO VVVV C V B II K VVV Å BB IIIII Mere af ældreplejen skal udliciteres til private virksomheder AAAA BB FFFFFF KKK OOO ØØØØØØØØØ ÅÅ AAAA BB KKK OOOO C KKK OO Å B CCCCC I K O VVVVVVVV IIIIII V Man skal hurtigere kunne genoptjene retten til dagpenge AAAAA B FFFFFF KKKKKK OOOOOOO BBB CCCC IIIIIII K VV CC O VVV AA B K O VV A KK OO VV Å ØØØØØØØØØ ÅÅ Virksomheder skal kunne drages til ansvar for, om deres udenlandske underleverandører i Danmark overholder danske regler om løn, moms og skat AAAAA BBB CC FFFFFF KKK B CC IIIIIII KK O VVV A C KKK O VVVV C O AA B KK O VV Å OOOOOO ØØØØØØØØØ ÅÅ Vækst i den offentlige sektor er vigtigere end skattelettelser B CCCCCC IIIIIII O VVVVVVVVV BB KK OO KKKK OO ÅÅ AAAAAA BB KKK OO Å AA FFFFFF K OOO ØØØØØØØØØ Investeringer i kollektiv trafik skal prioriteres højere end investeringer til fordel for privatbilisme III KK OOOOO VVV Ø CCC IIII OO VVVV AAA BB CC KKKK O V AAA BB C FFF KKKK O V Ø Å AA FFF O ØØØØØØØ ÅÅ Straffen for grov vold og voldtægt skal skærpes CCCC IIIIIII KKKK OOOOOOOOOO BBB F ØØØ A B -

19. Møde Forslag Til Lov Om Ændring Af Lov Om Planlægning Og Lov Om Midler- Tirsdag Den 17

Tirsdag den 17. november 2015 (D) 1 (Fremsættelse 11.11.2015). 8) 1. behandling af lovforslag nr. L 51: 19. møde Forslag til lov om ændring af lov om planlægning og lov om midler- Tirsdag den 17. november 2015 kl. 13.00 tidig regulering af boligforholdene. (Udvidelse af flexboligordnin- gen). Af erhvervs- og vækstministeren (Troels Lund Poulsen). Dagsorden (Fremsættelse 11.11.2015). 1) Spørgetime med statsministeren. 9) 1. behandling af lovforslag nr. L 45: Forslag til lov om ændring af kursgevinstloven, ligningsloven, pensi- 2) Fortsættelse af forespørgsel nr. F 2 [afstemning]: onsafkastbeskatningsloven, statsskatteloven og forskellige andre lo- Forespørgsel til justitsministeren om asyl-, flygtninge- og udlændin- ve. (Skattemæssig behandling af negative renter, forrentning af pen- gepolitik og retsforbeholdet. sionsafkastskat og renter vedrørende visse pensionsordninger m.v.). Af Kenneth Kristensen Berth (DF) og Claus Kvist Hansen (DF). Af skatteministeren (Karsten Lauritzen). (Anmeldelse 07.10.2015. Omtrykt. Fremme 20.10.2015. Forhand- (Fremsættelse 10.11.2015). ling 16.11.2015. Forslag til vedtagelse nr. V 6 af Trine Bramsen (S), Marcus Knuth (V), Sofie Carsten Nielsen (RV) og Rasmus Jarlov 10) 1. behandling af lovforslag nr. L 46: (KF). Forslag til vedtagelse nr. V 7 af Kenneth Kristensen Berth Forslag til lov om ændring af skattekontrolloven, arbejdsmarkedsbi- (DF). Forslag til vedtagelse nr. V 8 af Rasmus Nordqvist (ALT)). dragsloven, kildeskatteloven, ligningsloven og pensionsbeskatnings- loven. (Indførelse af land for land-rapportering for store multinatio- 3) 2. (sidste) behandling af beslutningsforslag nr. B 16: nale koncerner, gennemførelse af ændring af direktiv om administra- Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om Danmarks ratifikation af over- tivt samarbejde på beskatningsområdet m.v.). -

Opskriften På Succes Stort Tema Om Det Nye Politiske Landkort

UDGAVE NR. 5 EFTERÅR 2016 Uffe og Anders Opskriften på succes Stort tema om det nye politiske landkort MAGTDUO: Metal-bossen PORTRÆT: Kom tæt på SKIPPER: Enhedslistens & DI-direktøren Dansk Flygtningehjælps revolutionære kontrolfreak topchef www.mercuriurval.dk Ledere i bevægelse Ledelse i balance Offentlig ledelse + 150 85 250 toplederansættelser konsulenter over ledervurderinger og i den offentlige sektor hele landet udviklingsforløb på over de sidste tre år alle niveauer hvert år Kontakt os på [email protected] eller ring til os på 3945 6500 Fordi mennesker betyder alt EFTERÅR 2016 INDHOLD FORDOMME Levebrød, topstyring og superkræfter 8 PORTRÆT Skipper: Enhedslistens nye profil 12 NYBRUD Klassens nye drenge Anders Samuelsen og Uffe Elbæk giver opskriften på at lave et nyt parti. 16 PARTIER Nyt politisk kompas Hvordan ser den politiske skala ud i dag? 22 PORTRÆT CEO for flygningehjælpen A/S Kom tæt på to-meter-manden Andreas Kamm, som har vendt Dansk Flygtningehjælp fra krise til succes. 28 16 CIVILSAMFUND Danskerne vil hellere give gaver end arbejde frivilligt 34 TOPDUO Spydspidserne 52 Metal-bossen Claus Jensen og DI-direktøren Karsten Dybvad udgør et umage, men magtfuldt par. 40 INDERKREDS Topforhandlerne Mød efterårets centrale politikere. 44 INTERVIEW Karsten Lauritzen: Danmark efter Brexit 52 BAGGRUND Den blinde mand og 12 kampen mod kommunerne 58 KLUMME Klumme: Jens Christian Grøndahl 65 3 ∫magasin Efterår 2016 © �∫magasin er udgivet af netavisen Altinget ANSVARSHAVENDE CHEFREDAKTØR Rasmus Nielsen MAGASINREDAKTØR Mads Bang REDAKTION Anders Jerking Erik Holstein Morten Øyen Jensen Klaus Ulrik Mortensen Kasper Frandsen Mads Bang Hjalte Kragesteen Sine Riis Lund Kim Rosenkilde Rikke Albrechtsen Anne Justesen Frederik Tillitz Erik Bjørn Møller Toke Gade Crone Kristiansen Søren Elkrog Friis Emma Qvirin Holst Carsten Terp Rasmus Løppenthin Amalie Bjerre Christensen Tyson W. -

Betænkning Afgivet Af Sundhedsudvalget Den 9

Til beslutningsforslag nr. B 30 Folketinget 2020-21 Betænkning afgivet af Sundhedsudvalget den 9. marts 2021 Betænkning over Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om indførelse af en pligt til indhentning af offentlige straffeattester ved ansættelse af personale og ledelse i pleje- og omsorgssektoren [af Karina Adsbøl (DF) m.fl.] 1. Indstillinger straffeattester til understøttelse af deres ansættelsesprocedu‐ Et flertal i udvalget (S, V, SF, RV, KF, NB og Susanne rer. Det vurderes derfor hensigtsmæssigt at afvente erfarin‐ Zimmer (UFG)) indstiller beslutningsforslaget til forkastel‐ gerne fra børne- og handicapområdet om pligt til indhentelse se. af straffeattester i forbindelse med ansættelser i konkrete Et mindretal i udvalget (DF, EL og NB) indstiller beslut‐ sociale tilbud forud for tilføjelser af yderligere regler og ningsforslaget til vedtagelse uændret. økonomiske udgifter inden for pleje- og omsorgssektoren. Alternativet, Inuit Ataqatigiit, Siumut, Sambandsflokkur‐ in og Javnaðarflokkurin havde ved betænkningsafgivelsen 3. Udvalgsarbejdet ikke medlemmer i udvalget og dermed ikke adgang til at Beslutningsforslaget blev fremsat den 8. oktober 2020 komme med indstillinger eller politiske bemærkninger i be‐ og var til 1. behandling den 13. januar 2021. Beslutnings‐ tænkningen. forslaget blev efter 1. behandling henvist til behandling i En oversigt over Folketingets sammensætning er optrykt Sundhedsudvalget. i betænkningen. Oversigt over beslutningsforslagets sagsforløb og 2. Politiske bemærkninger dokumenter Beslutningsforslaget og dokumenterne i forbindelse med Socialdemokratiet, Venstre, Socialistisk Folkeparti og udvalgsbehandlingen kan læses under beslutningsforslaget Radikale Venstre på Folketingets hjemmeside www.ft.dk. Socialdemokratiets, Venstres, Socialistisk Folkepartis og Radikale Venstres medlemmer af udvalget finder, at det er Møder vigtigt, at vi har en ældrepleje, hvor der er fokus på de Udvalget har behandlet beslutningsforslaget i 2 møder. -

2. Udkast Betænkning Forslag Til Lov Om Ændring Af Lov Om Social Pension

Beskæftigelsesudvalget 2014-15 (2. samling) L 3 Bilag 8 Offentligt Til lovforslag nr. L 3 Folketinget 2014-15 (2. samling) Betænkning afgivet af Beskæftigelsesudvalget den 00. august 2015 2. udkast til Betænkning over Forslag til lov om ændring af lov om social pension (Harmonisering af regler om opgørelse af bopælstid for folkepension) [af beskæftigelsesministeren (Jørn Neergaard Larsen)] 1. Udvalgsarbejdet og Mødestedet, Folkekirkens Flygtninge- og Indvandrear- Lovforslaget blev fremsat den 3. juli 2105 og var til 1. bejde på Vesterbro. behandling den 3. juli 2015. Lovforslaget blev efter 1. be- Beskæftigelsesministeren har over for udvalget kommen- handling henvist til behandling i Beskæftigelsesudvalget. teret de skriftlige henvendelser til udvalget. Møder Samrådsspørgsmål Udvalget har behandlet lovforslaget i 1 møde. Udvalget har stillet et samrådsspørgsmål til mundtlig be- svarelse til beskæftigelsesministeren, udlændinge-, integrati- Høring ons- og boligministeren og skatteministeren. [Ministrene har Et udkast til lovforslaget blev samtidig med fremsættel- besvaret spørgsmålet i et fælles åbent samråd mellem Be- sen sendt i høring. Den 29. juli 2015 og 6. august 2015 skæftigelsesudvalget, Skatteudvalget og Udlændinge-, Inte- sendte beskæftigelsesministeren de indkomne høringssvar til grations- og Boligudvalget den 18. august 2015. Ministrene udvalget. Den 10. august 2015 sendte beskæftigelsesmini- har efterfølgende sendt udvalget de(t) talepapir(er), der lå til steren yderligere høringssvar og et notat om samtlige hø- grund for ministrenes besvarelse af spørgsmålet. ] ringssvar til udvalget. Spørgsmål Sammenhæng med andre lovforslag Udvalget har stillet 8 spørgsmål til beskæftigelsesmini- Lovforslaget skal ses i sammenhæng med lovforslag nr. steren til skriftlig besvarelse, som denne har besvaret. L 2 om ændring af lov om aktiv socialpolitik, lov om en ak- tiv beskæftigelsesindsats, integrationsloven og forskellige 2. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

99. Møde Per Larsen (KF) Onsdag Den 21

Onsdag den 21. april 2021 (D) 1 (Spm. nr. S 1325). 4) Til sundhedsministeren af: 99. møde Per Larsen (KF) Onsdag den 21. april 2021 kl. 13.00 Hvad er ministerens holdning til, at den nye vaccinationsplan i ud‐ gangspunktet ikke sikrer yngre personer med f.eks. alvorlige eller kroniske sygdomme, som nu må vente med at blive vaccineret, da Dagsorden man er gået over til at vaccinere efter alder? (Spm. nr. S 1326). 1) Besvarelse af oversendte spørgsmål til ministrene (spørgetid). (Se nedenfor). 5) Til sundhedsministeren af: Pernille Skipper (EL) 2) 1. behandling af lovforslag nr. L 194: Hvad kan ministeren oplyse om konsekvenserne for landets fødegan‐ Forslag til lov om ændring af lov om almene boliger m.v., lov om le‐ ge, hvis hver fjerde jordemoder vælger ikke at tage arbejde i den je af almene boliger og lov om leje. (Tidligere hårde ghettoområder, offentlige sektor, jf. artiklen »Mere end hver fjerde af landets jorde‐ som er omfattet af en udviklingsplan). mødre nægter at arbejde i den offentlige sektor« fra Berlingske den Af indenrigs- og boligministeren (Kaare Dybvad Bek). 8. april 2021, og hvad vil ministeren gøre for at forhindre, at et stort (Fremsættelse 24.03.2021). antal jordemødre fravælger at arbejde på landets fødegange på grund af de nuværende løn- og arbejdsvilkår? 3) Forhandling om redegørelse nr. R 13: (Spm. nr. S 1334). Udenrigsministerens redegørelse om udvalgte internationale organi‐ sationer (OSCE, Europarådet og Østersørådet). 6) Til sundhedsministeren af: (Anmeldelse 10.03.2021. Redegørelse givet 10.03.2021. Meddelelse Peter Juel-Jensen (V) om forhandling 10.03.2021). -

Lapa Public Lectures and Workshops

LAPA PUBLIC LECTURES AND WORKSHOPS In addition to LAPA’s regular seminar series and conference events, LAPA also sponsors or cosponsors public lectures, informal workshops and other events that are not part of a regular series. Those events are listed here, from the most recent back to LAPA’s beginnings. Robert C. Post, David Boies Professor of Law at Yale Law School Third Annual Donald S. Bernstein ’75 Lecture May 3, 2007, 4:30 pm Robert C. Post joined the Yale faculty as the first David Boies Professor of Law. He focuses his teaching and writing on constitutional law, and is a specialist in the area of First Amendment theory and constitutional jurisprudence. Before coming to Yale Law, he had been teaching since 1983 at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law (Boalt Hall). Post is the author of Constitutional Domains: Democracy, Community, Management and co-author with K. Anthony Appiah, Judith Butler, Thomas C. Grey and Reva Siegel of Prejudicial Appearances: The Logic of American Antidiscrimination Law. He edited or co- edited Civil Society and Government, Human Rights in Political Transitions: Gettysburg to Bosnia, Race and Representation: Affirmative Action, Censorship and Silencing: Practices of Cultural Regulation and Law and Order of Culture. His scholarship has appeared academic journals in the humanities as well as in dozens of important law review articles, many in recent years with his colleague Reva Siegel. In 2003, he wrote the important Harvard Law Review “foreword” to its annual review of Supreme Court jurisprudence. Post was a law clerk to Chief Judge David L. -

Forslag Til Folketingsbeslutning Om, at Danmark Ved Modtagelse Af Kvoteflygtninge Prioriterer Modtagelse Af Forfulgte Kristne Og Andre Religiøse Minoriteter

Udskriftsdato: 24. september 2021 2019/1 BSF 157 (Gældende) Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om, at Danmark ved modtagelse af kvoteflygtninge prioriterer modtagelse af forfulgte kristne og andre religiøse minoriteter Ministerium: Folketinget Fremsat den 10. marts 2020 af Marcus Knuth (KF), Katarina Ammitzbøll (KF), Birgitte Bergman (KF), Rasmus Jarlov (KF), Brigitte Klintskov Jerkel (KF), Naser Khader (KF), Mai Mercado (KF) og Søren Pape Poulsen (KF) Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om, at Danmark ved modtagelse af kvoteflygtninge prioriterer modtagelse af forfulgte kristne og andre religiøse minoriteter Regeringen pålægges at sikre, at det prioriteres at modtage forfulgte kristne og andre religiøse minorite ter, når Danmark tager imod kvoteflygtninge. 2019/1 BSF 157 1 Bemærkninger til forslaget Af regeringens aftale om finanslov for 2020 fremgår det, at Danmark igen skal tage imod kvoteflygtnin ge. Forslagsstillerne mener ikke, at Danmark p.t. bør åbne op for kvoteflygtninge, da der fortsat er for store udfordringer med integrationen i Danmark og med tilstrømningen af asylansøgere. Hvis regeringen alligevel beslutter igen at tage imod kvoteflygtninge, er det forslagsstillernes klare overbevisning, at der skal sættes særligt fokus på forfulgte kristne og andre religiøse minoriteter. I dag har man allerede mulighed for at udvælge kvoteflygtninge fra forskellige geografiske områder. Det anslås, at der er over 300 millioner forfulgte kristne, som dermed er den mest udsatte religiøse minoritet i verden. Særlig slemt står det til med forfulgte kristne i Mellemøsten. Det afslører den nye World Watch List for 2020, som er en liste over lande, hvor verdens kristne forfølges for at udøve deres tro (»The pressure is on«, World Watch List 2020, side 13, Open Doors, 2020). -

26. Møde Hasteforespørgsel Nr

Fredag den 27. november 2020 (D) 1 Martin Geertsen (V), Liselott Blixt (DF), Per Larsen (KF), Lars Boje Mathiesen (NB) og Henrik Dahl (LA): 26. møde Hasteforespørgsel nr. F 25 (Om en ny epidemilov med udgangspunkt Fredag den 27. november 2020 kl. 10.00 i folkestyre, retssikkerhed og transparens) (Vil ministeren redegøre for, hvordan ministeren vil sikre en hurtig behandling og vedtagelse af en ny epidemilov med udgangspunkt i folkestyre, retssikkerhed og Dagsorden transparens?)). 1) 1. behandling af lovforslag nr. L 100: Titlen på den anmeldte sag vil fremgå af www.folketingstidende.dk Forslag til lov om ændring af lov om tilgængelighed af offentlige (jf. ovenfor). organers websteder og mobilapplikationer. (Justering af undtagelse for tredjepartsindhold på offentlige organers websteder og mobilap‐ Socialdemokratiets folketingsgruppe har meddelt mig, at medlem plikationer). af Folketinget hr. Leif Lahn Jensen er udpeget som medlem af Løn‐ Af finansministeren (Nicolai Wammen). ningsrådet i stedet for medlem af Folketinget hr. Flemming Møller (Fremsættelse 12.11.2020). Mortensen for den resterende del af indeværende funktionsperiode. Den pågældende er herefter valgt. 2) 1. behandling af lovforslag nr. L 108: Forslag til lov om ændring af lov om offentlige betalinger m.v. Socialdemokratiets folketingsgruppe har meddelt mig, at den til (Nemkontosystemet stilles til rådighed for grønlandske myndighe‐ Danmarks Nationalbanks Repræsentantskab har udpeget medlem der). af Folketinget hr. Christian Rabjerg Madsen som medlem for den Af finansministeren (Nicolai Wammen). resterende del af indeværende funktionsperiode i stedet for medlem (Fremsættelse 19.11.2020). af Folketinget hr. Flemming Møller Mortensen. Den pågældende er herefter valgt. 3) Forhandling om redegørelse nr. R 9: Sundheds- og ældreministerens redegørelse om ældreområdet 2020.