What (Not) to Do with the Trinity: Doctrine, Discipline, and Doxology in Contemporary Trinitarian Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psalm 150 “Living Doxology” Grace to You and Peace From

Season after Pentecost - Psalm 150 July 9, 2017 Haven Lutheran Church Hagerstown MD Readings: John 4: 24-26; Psalm 150 “Living Doxology” Grace to you and peace from God - Father, Son, Holy Spirit. Amen A man was visiting a church for the first time. He was moved by something the pastor said in his sermon, so with a loud voice he shouted, ““Praise the Lord.” Hearing it, a well-meaning member leaned over and tapped him on the shoulder saying, “Sir, we don’t ‘praise the Lord’ here.’ To which another member leaned over and said, “Oh yes we do, we just do it all together when we sing the doxology.” When I attended my first Lutheran potluck supper, the pastor suggested we sing the doxology as our grace before the meal. I had no idea what he was talking about but everyone else seemed to. Together they sang: “Praise God from whom all blessings flow Praise him all creatures here below Praise him above ye heavenly hosts. Praise Father, Son and Holy Ghost. Amen” I wondered where the words were so I could learn it. I wondered why these Lutherans were singing a song with a Latin word title — Doxology. The word doxology is derived from Latin but came down from Greek - doxo = glory/praise, logo - Word. If you look it up in the dictionary, it will say doxology is a “hymn of praise.” When we suggest singing THE Doxology, we are specifically referring to the hymn we just sang. That particular doxology was written by Anglican Bishop Thomas Ken in the late 1600s. -

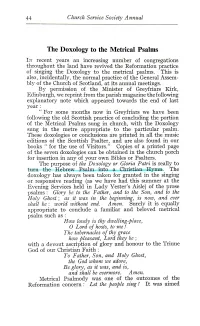

The Doxology to the Metrical Psalms

44 Church Service Society Annual The Doxology to the Metrical Psalms IN recent years an increasing number of congregations throughout the land have revived the Reformation practice of singing the Doxology to the metrical psalms. This is also, incidentally, the normal practice of the General Assem- bly of the Church of Scotland, at its annual meetings. By permission of the Minister of Greyfriars Kirk, Edinburgh, we reprint from the parish magazine the following explanatory note which appeared towards the end of last year : " For some months now in Greyfriars we have been following the old Scottish practice of concluding the portion of the Metrical Psalms sung in church, with the Doxology sung in the metre appropriate to the particular psalm. These doxologies or conclusions are printed in all the music editions of the Scottish Psalter, and are also found in our books " for the use of Visitors." Copies of a printed page of the seven doxologies can be obtained in the church porch for insertion in any of your own Bibles or Psalters. The purpose of the Doxology or Gloria Patri is really to turn the Hebrew Psalm into a Christian Hymn. The doxology has always been taken for granted in the singing or responsive reading (as we have had this summer at the Evening Services held in Lady Yester's Aisle) of the prose psalms : Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost ; as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be : world without end. Amen. Surely it is equally appropriate to conclude a familiar and beloved metrical psalm such as : How lovely is thy dwelling-place, 0 Lord of hosts, to me ! The tabernacles of thy grace how pleasant, Lord they be ; with a devout ascription of glory and honour to the Triune God of our Christian Faith : To Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, the God whom we adore, Be glory, as it was, and is, and shall be evermore. -

Chapter 1 the Trinity in the Theology of Jürgen Moltmann

Our Cries in His Cry: Suffering and The Crucified God By Mick Stringer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Theology The University of Notre Dame Australia, Fremantle, Western Australia 2002 Contents Abstract................................................................................................................ iii Declaration of Authorship ................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements.............................................................................................. v Introduction.......................................................................................................... 1 1 Moltmann in Context: Biographical and Methodological Issues................... 9 Biographical Issues ..................................................................................... 10 Contextual Issues ........................................................................................ 13 Theological Method .................................................................................... 15 2 The Trinity and The Crucified God................................................................ 23 The Tradition............................................................................................... 25 Divine Suffering.......................................................................................... 29 The Rise of a ‘New Orthodoxy’................................................................. -

V.C. Samuel. "Some Facts About the Alexandrine Christology," Indian

Some Facts About the Alexandrine Ch~istology V. C. SAMUEL Modern N estorian studies have had a number of significant consequences for our understanding of the fifth-century Christo logical controversies. For one thing, it has led a number of scholars in the present century to show an unprecedented ap preciation for the theological position associated with the name of N estorius. Though the study of the documents connected with the teaching of the N estorian, or the Antiochene; school helped this movement, the ground had been prepared for it by modern Liberalism. Traceable to Schleiermacher and Ritschl, it had left no room for a conception pf our Lord which does not see Him first and foremost as a man. Against this intellectual background of the modern theologian the N estorian studies disclosed the fact that the teaching of that ancient school of theological thinking also emphasized the full humanity of our Lord. Naturally, many in our times have been drawn to appraise it favourably, From this appreciation for the Nestorian school many have gone a step further in offering an added defence of the doctrinal formula adopted by the Council of Chalcedon in 451. One of the ablest presentations of this point of view in recent times may be found in W. Norman Pittenger's book, The Word Incarnate, published in 1959 by Harper and Brothers, New York, for 'The Library of Constructive Theology·. An eminent Pro fessor at the General Theological Seminary in New York, Dr. Pittenger is one of the top-level theologians of the American con tinent. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

Sacramental Symbols in a Time of Violence Requires It Constantly and Dances with It

SACRAMENTS REVELATION OF THE HUMANITY OF GOD Engaging the Fundamental Theology of Louis-Marie Chauvet Edited by Philippe Bordeyne and Bruce T. Morrill A PUEBLO BOOK Liturgical Press Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org Thus we cannot separate the metaphorical word and symbol; we can barely distinguish them. Since in the metaphor there is the possi bility of becoming a symbol, thanks to the genius of the poet, there is in the symbol a metaphorical process of translation of meaning, even if, as we have attempted to say, the symbol is the conveyer of the real to the real. The category of "play" would be the most appropriate to Chapter 10 account for the nature of the symbol. Thus the play between logos and bios allows us to understand that the symbol is more than language yet Sacramental Symbols in a Time of Violence requires it constantly and dances with it. and Disruption: CONCLUSION The anthropological and philosophical approach to symbol can go Shaping a People of Hope beyond its ever-open frontier toward a theology of sacrament. For if and Eschatological Vision the God of Jesus Christ is the Totally Other, he is also the Totally Near, and he is really in symbolic and sacramental relationship with us. Judith M. Kubicki, CSSF Thus, it seems that the symbol is, according to its etymology, this con crete mediation, metaphorical and anaphoric, that allows us to navi gate between worlds. When the theologian becomes anthropologist,'H this INTRODUCTION symbol-sacrament rediscovers its human roots, and when the anthro The classic novel, A Tale of Two Cities, by Charles Dickens, opens pologist becomes theologian, passing through philosophy, the symbol with the following lines: sacrament ontologically returns to its divine aim. -

A Concise Glossary of the Genres of Eastern Orthodox Hymnography

Journal of the International Society for Orthodox Church Music Vol. 4 (1), Section III: Miscellanea, pp. 198–207 ISSN 2342-1258 https://journal.fi/jisocm A Concise Glossary of the Genres of Eastern Orthodox Hymnography Elena Kolyada [email protected] The Glossary contains concise entries on most genres of Eastern Orthodox hymnography that are mentioned in the article by E. Kolyada “The Genre System of Early Russian Hymnography: the Main Stages and Principles of Its Formation”.1 On the one hand the Glossary is an integral part of the article, therefore revealing and corroborating its principal conceptual propositions. However, on the other hand it can be used as an independent reference resource for hymnographical terminology, useful for the majority of Orthodox Churches worldwide that follow the Eastern Rite: Byzantine, Russian, Bulgarian, Serbian et al., as well as those Western Orthodox dioceses and parishes, where worship is conducted in English. The Glossary includes the main corpus of chants that represents the five great branches of the genealogical tree of the genre system of early Christian hymnography, together with their many offshoots. These branches are 1) psalms and derivative genres; 2) sticheron-troparion genres; 3) akathistos; 4) canon; 5) prayer genres (see the relevant tables, p. 298-299).2 Each entry includes information about the etymology of the term, a short definition, typological features and a basic statement about the place of a particular chant in the daily and yearly cycles of services in the Byzantine rite.3 All this may help anyone who is involved in the worship or is simply interested in Orthodox liturgiology to understand more fully specific chanting material, as well as the general hymnographic repertoire of each service. -

Getting Back to Idolatry Critique: Kingdom, Kin-Dom, and the Triune

86 87 Getting Back to Idolatry Critique: Kingdom, Critical theory’s concept of ideology is helpful, but when it flattens the idolatry critique by identifying idolatry as ideology, and thus making them synonymous, Kin-dom, and the Triune Gift Economy ideology ultimately replaces idolatry.4 I suspect that ideology here passes for dif- fering positions within sheer immanence, and therefore unable to produce a “rival David Horstkoetter universality” to global capitalism.5 Therefore I worry that the political future will be a facade of sheer immanence dictating action read as competing ideologies— philosophical positions without roots—under the universal market.6 Ideology is thus made subject to the market’s antibodies, resulting in the market commodi- Liberation theology has largely ceased to develop critiques of idolatry, espe- fying ideology. The charge of idolatry, however, is rooted in transcendence (and cially in the United States. I will argue that the critique is still viable in Christian immanence), which is at the very least a rival universality to global capitalism; the theology and promising for the future of liberation theology, by way of reformu- critique of idolatry assumes divine transcendence and that the incarnational, con- lating Ada María Isasi-Díaz’s framework of kin-dom within the triune economy. structive project of divine salvation is the map for concrete, historical work, both Ultimately this will mean reconsidering our understanding of and commitment to constructive and critical. This is why, when ideology is the primary, hermeneutical divinity and each other—in a word, faith.1 category, I find it rather thin, unconvincing, and unable to go as far as theology.7 The idea to move liberation theology from theology to other disciplines Also, although sociological work is necessary, I am not sure that it is primary for drives discussion in liberation theology circles, especially in the US, as we talk realizing divine work in history. -

The Book of Alternative Services of the Anglican Church of Canada with the Revised Common Lectionary

Alternative Services The Book of Alternative Services of the Anglican Church of Canada with the Revised Common Lectionary Anglican Book Centre Toronto, Canada Copyright © 1985 by the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada ABC Publishing, Anglican Book Centre General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada 80 Hayden Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4Y 3G2 [email protected] www.abcpublishing.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. Acknowledgements and copyrights appear on pages 925-928, which constitute a continuation of the copyright page. In the Proper of the Church Year (p. 262ff) the citations from the Revised Common Lectionary (Consultation on Common Texts, 1992) replace those from the Common Lectionary (1983). Fifteenth Printing with Revisions. Manufactured in Canada. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Anglican Church of Canada. The book of alternative services of the Anglican Church of Canada. Authorized by the Thirtieth Session of the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada, 1983. Prepared by the Doctrine and Worship Committee of the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada. ISBN 978-0-919891-27-2 1. Anglican Church of Canada - Liturgy - Texts. I. Anglican Church of Canada. General Synod. II. Anglican Church of Canada. Doctrine and Worship Committee. III. Title. BX5616. A5 1985 -

The Trinitarian Ecclesiology of Thomas F. Torrance

The Trinitarian Ecclesiology of Thomas F. Torrance Kate Helen Dugdale Submitted to fulfil the requirements for a Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Otago, November 2016. 1 2 ABSTRACT This thesis argues that rather than focusing on the Church as an institution, social grouping, or volunteer society, the study of ecclesiology must begin with a robust investigation of the doctrine of the Holy Trinity. Utilising the work of Thomas F. Torrance, it proposes that the Church is to be understood as an empirical community in space and time that is primarily shaped by the perichoretic communion of Father, Son and Holy Spirit, revealed by the economic work of the Son and the Spirit. The Church’s historical existence is thus subordinate to the Church’s relation to the Triune God, which is why the doctrine of the Trinity is assigned a regulative influence in Torrance’s work. This does not exclude the essential nature of other doctrines, but gives pre-eminence to the doctrine of the Trinity as the foundational article for ecclesiology. The methodology of this thesis is one of constructive analysis, involving a critical and constructive appreciation of Torrance’s work, and then exploring how further dialogue with Torrance’s work can be fruitfully undertaken. Part A (Chapters 1-5) focuses on the theological architectonics of Torrance’s ecclesiology, emphasising that the doctrine of the Trinity has precedence over ecclesiology. While the doctrine of the Church is the immediate object of our consideration, we cannot begin by considering the Church as a spatiotemporal institution, but rather must look ‘through the Church’ to find its dimension of depth, which is the Holy Trinity. -

1 Trinity, Filioque and Semantic Ascent Christians Believe That The

Trinity, Filioque and Semantic Ascent1 Christians believe that the Persons of the Trinity are distinct but in every respect equal. We believe also that the Son and Holy Spirit proceed from the Father. It is difficult to reconcile claims about the Father’s role as the progenitor of Trinitarian Persons with commitment to the equality of the persons, a problem that is especially acute for Social Trinitarians. I propose a metatheological account of the doctrine of the Trinity that facilitates the reconciliation of these two claims. On the proposed account, “Father” is systematically ambiguous. Within economic contexts, those which characterize God’s relation to the world, “Father” refers to the First Person of the Trinity; within theological contexts, which purport to describe intra-Trinitarian relations, it refers to the Trinity in toto-- thus in holding that the Son and Holy Spirit proceed from the Father we affirm that the Trinity is the source and unifying principle of Trinitarian Persons. While this account solves a nagging problem for Social Trinitarians it is theologically minimalist to the extent that it is compatible with both Social Trinitarianism and Latin Trinitarianism, and with heterodox Modalist and Tri-theist doctrines as well. Its only theological cost is incompatibility with the Filioque Clause, the doctrine that the Holy Spirit proceeds from both the Father and the Son—and arguably that may be a benefit. 1. Problem: the equality of Persons and asymmetry of processions In addition to the usual logical worries about apparent violations of transitivity of identity, the doctrine of the Trinity poses theological problems because it commits us to holding that there are asymmetrical quasi-causal relations amongst the Persons: the Father “begets” the Son and “spirates” the Holy Spirit. -

The Doxology

ST P AUL ’S E PISCOPAL C HURCH † J ULY 2009 ST P AUL ’S E PISCOPAL C HURCH † J ULY 2009 THE E PISTLE THE D OXOLOGY “Doxology” is a praise state- has to do with how we feel your car onto the side of the ment or praise hymn. In and how we act toward road. Keep your cars in THE D OXOLOGY our tradition it is praise to others and other things. It good operating condition so God, Father, Son, and Holy means that we act and feel they don’t pollute the air. Spirit. The sung version is thankful for the things of Show respect for God’s Praise God from found within hymns. The our world and the people of creation. one most familiar to most of our world. whom all blessings Doxological living means to us is some version of “Old flow. 100.” In our Hymnal 1982 it is found in Praise him all the last verse creatures here of Hymn 380. This of course below. is only one doxology. Praise him above Our Eucharis- tic prayers The the Heavenly conclude with doxologies. Host. The 1979 Book of Com- Doxology Praise Father, Son mon Prayer has versions and Holy Ghost. of the Lord’s prayers with Amen and without doxological endings - with INSIDE THIS ISSUE : praise and There has been an increased assume responsibility for without. The Biblical ver- concern for the environ- those things for which we sions of the prayer our Lord ment expressed in state- can control. Living in this taught us do not have a dox- ments like “think green.” way does not blame others, ology at the end.