Kimono Galleryguide Web.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identification of Asian Garments in Small Museums

AN ABSTRACTOF THE THESIS OF Alison E. Kondo for the degree ofMaster ofScience in Apparel Interiors, Housing and Merchandising presented on June 7, 2000. Title: Identification ofAsian Garments in Small Museums. Redacted for privacy Abstract approved: Elaine Pedersen The frequent misidentification ofAsian garments in small museum collections indicated the need for a garment identification system specifically for use in differentiating the various forms ofAsian clothing. The decision tree system proposed in this thesis is intended to provide an instrument to distinguish the clothing styles ofJapan, China, Korea, Tibet, and northern Nepal which are found most frequently in museum clothing collections. The first step ofthe decision tree uses the shape ofthe neckline to distinguish the garment's country oforigin. The second step ofthe decision tree uses the sleeve shape to determine factors such as the gender and marital status ofthe wearer, and the formality level ofthe garment. The decision tree instrument was tested with a sample population of 10 undergraduates representing volunteer docents and 4 graduate students representing curators ofa small museum. The subjects were asked to determine the country oforigin, the original wearer's gender and marital status, and the garment's formality and function, as appropriate. The test was successful in identifying the country oforigin ofall 12 Asian garments and had less successful results for the remaining variables. Copyright by Alison E. Kondo June 7, 2000 All rights Reserved Identification ofAsian Garments in Small Museums by Alison E. Kondo A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master ofScience Presented June 7, 2000 Commencement June 2001 Master of Science thesis ofAlison E. -

Typical Japanese Souvenirs Are a Kimono Or Yukata (Light, Cotton

JAPAN K N O W B E F O R E Y O U G O PASSPORT & VISA IMMUNIZATIONS All American and While no immunizations Canadian citizens must are required, you should have a passport which is consult your medical valid for at least 3 months provider for the most after your return date. No current advice. visa is required for stays See Travelers Handbook for up to 90 days. more information. ELECTRICITY TIME ZONE Electricity in Japan is 100 Japan is 13 hours ahead of volts AC, close to the U.S., Eastern Standard Time in our which is 120 volts. A voltage summer. Japan does not converter and a plug observe Daylight Saving adapter are NOT required. Time and the country uses Reduced power and total one time zone. blackouts may occur sometimes. SOUVENIRS Typical Japanese souvenirs CURRENCY are a Kimono or Yukata (light, The Official currency cotton summer Kimono), of Japan is the Yen (typically Geta (traditional footwear), in banknotes of 1,000, 5,000, hand fans, Wagasa and 10,000). Although cash (traditional umbrella), paper is the preferred method of lanterns, and Ukiyo-e prints. payment, credit cards are We do not recommend accepted at hotels and buying knives or other restaurants. Airports are weapons as they can cause best for exchanging massive delays at airports. currency. WATER WiFi The tap water is treated WiFi is readily available and is safe to drink. There at the hotels and often are no issues with washing on the high speed trains and brushing your teeth in and railways. -

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei By ©2016 Alison Miller Submitted to the graduate degree program in the History of Art and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko ________________________________ Dr. Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Dr. David Cateforis ________________________________ Dr. John Pultz ________________________________ Dr. Akiko Takeyama Date Defended: April 15, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Alison Miller certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko Date approved: April 15, 2016 ii Abstract This dissertation examines the political significance of the image of the Japanese Empress Teimei (1884-1951) with a focus on issues of gender and class. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, Japanese society underwent significant changes in a short amount of time. After the intense modernizations of the late nineteenth century, the start of the twentieth century witnessed an increase in overseas militarism, turbulent domestic politics, an evolving middle class, and the expansion of roles for women to play outside the home. As such, the early decades of the twentieth century in Japan were a crucial period for the formation of modern ideas about femininity and womanhood. Before, during, and after the rule of her husband Emperor Taishō (1879-1926; r. 1912-1926), Empress Teimei held a highly public role, and was frequently seen in a variety of visual media. -

Global Education for Young Children: a Curriculum Unit for the Kindergarten Classroom Ann Davis Cannon University of North Florida

UNF Digital Commons UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 1984 Global Education for Young Children: A Curriculum Unit for the Kindergarten Classroom Ann Davis Cannon University of North Florida Suggested Citation Cannon, Ann Davis, "Global Education for Young Children: A Curriculum Unit for the Kindergarten Classroom" (1984). UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 22. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/etd/22 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 1984 All Rights Reserved GLOBAL EDUCATION FOR YOUNG CHILDREN: A CURRICULUM UNIT FOR THE KINDERGARTEN CLASSROOM by Ann Davis Cannon A thesis submitted to the Division of Curriculum and Instruction in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Education UNIVERSITY OF NORTH FLORIDA COLLEGE OF EDUCATION AND HUMAN SERVICES August, 1984 Signature Deleted Dr. Mary SuTerrell, Advisor Signature Deleted Signature Deleted Global Education ABSTRACT The purpose of this project was to develop a curriculum for global education appropriate for kindergarten children. A review of relevant literature provided concepts and themes that researchers consider essential components for inclusion in any global education program. Recommendations were made as to when and how the subject should be introduced in the classroom. Activities emphasized three important themes: We are one race, the human race, living on a small planet, earth; people are more alike than they are different, basic human needs bind people together; and, people of the world, even with different points of view, can live, work together, and learn from each other. -

The Male Fashion Bias Mr. Mark Neighbour a Practice

The Male Fashion Bias Mr. Mark Neighbour A Practice-Led Masters by Research Degree Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology Discipline: Fashion Year of Submission: 2008 Key Words Male fashion Clothing design Gender Tailoring Clothing construction Dress reform Innovation Design process Contemporary menswear Fashion exhibition - 2 - Abstract Since the establishment of the first European fashion houses in the nineteenth century the male wardrobe has been continually appropriated by the fashion industry to the extent that every masculine garment has made its appearance in the female wardrobe. For the womenswear designer, menswear’s generic shapes are easily refitted and restyled to suit the prevailing fashionable silhouette. This, combined with a wealth of design detail and historical references, provides the cyclical female fashion system with an endless supply of “regular novelty” (Barthes, 2006, p.68). Yet, despite the wealth of inspiration and technique across both male and female clothing, the bias has largely been against menswear, with limited reciprocal benefit. Through an exploration of these concepts I propose to answer the question; how can I use womenswear patternmaking and construction technique to implement change in menswear design? - 3 - Statement of Original Authorship The work contained in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree or diploma at any other higher educational institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made. Signed: Mark L Neighbour Dated: - 4 - Acknowledgements I wish to thank and acknowledge everyone who supported and assisted this project. -

Diana's Favorite Things

Diana’s Favorite Things By Trail End State Historic Site Curator Dana Prater; from Trail End Notes, March 2000 “Girls in white dresses with blue satin sashes ... “ Although we didn’t find a blue satin sash, we recently discovered something even better. While cataloging items from the Manville Kendrick Estate collection, we had the pleasure of examining some fantastic dresses that belonged to Manville’s wife, Diana Cumming Kendrick. Fortunately for us, Diana saved many of her favorite things, and these dresses span almost sixty years of fashion history. Diana Cumming (far right) and friends, c1913 (Kendrick Collection, TESHS) Few things reveal as much about our personalities and lifestyles as our clothing, and Diana Kendrick’s clothes are no exception. There are two silk taffeta party dresses dating from around 1914-1916 and worn when Diana was a young teenager. The pink one is completely hand sewn and the rounded neckline and puffy sleeves are trimmed with beaded flowers on a net background. Pinked and ruched fabric ribbons loop completely around the very full skirt, which probably rustled delightfully when she danced. The pale green gown consists of an overdress with a shorter skirt and an underdress - almost like a slip. The skirt of the slip has the same pale green fabric and extends out from under the overskirt. Both skirt layers have a scalloped hem. A short bertha (like a stole) is attached at the back of the rounded neckline and wraps around the shoulders, repeating the scalloped motif and fastening at the front. This dress even includes a mini-bustle of stiff buckram to add fullness in the back. -

Shigisan Engi Shigisan Engi Overview

Shigisan engi Shigisan engi Overview I. The Shigisan engi or Legends of the Temple on Mount Shigi consists of three handscrolls. Scroll 1 is commonly called “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 2 “The Exorcism of the Engi Emperor,” and Scroll 3 “The Story of the Nun.” These scrolls are a pictorial presentation of three legends handed down among the common people. These legends appear under the title “Shinano no kuni no hijiri no koto” (The Sage of Shinano Province) in both the Uji sh¯ui monogatari (Tales from Uji) and the Umezawa version of the Kohon setsuwash¯u (Collection of Ancient Legends). Since these two versions of the legends are quite similar, one is assumed to be based on the other. The Kohon setsuwash¯u ver- sion is written largely in kana, the phonetic script, with few Chinese characters and is very close to the text of the Shigisan engi handscrolls. Thus, it seems likely that there is a deep connection between the Shigisan engi and the Kohon setsuwash¯u; one was probably the basis for the other. “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 1 of the Shigisan engi, lacks the textual portion, which has probably been lost. As that suggests, the Shigisan engi have not come down to us in their original form. The Shigisan Ch¯ogosonshiji Temple owns the Shigisan engi, and the lid of the box in which the scrolls were stored lists two other documents, the Taishigun no maki (Army of Prince Sh¯otoku-taishi) and notes to that scroll, in addition to the titles of the three scrolls. -

My Kimono Kick

My Kimono Kick 着物の楽しみ Natalya Rodriguez ナタリア・ロドリゲス 私が日本に越してきてすぐのある日、びっくりするような贈り物が送られてきました。中には、私の祖母が横浜の近くの One day soon after I had moved to Japan, I received a surprise package in the mail. Inside I found a bunch of black and アメリカン・スクールで教師をしていた時の、(若い頃の)祖母の写真が大量に入っていました。そのうちの1枚には、祖 white pictures of my (young!) grandma during her time as a teacher at an American school near Yokohama. One of the 母が着物を着た姿が写っていて、写真の下には、まさにその着物が、長年しまい込まれた香りとともに、帯、草履、足袋 pictures showed her dressed in kimono, and beneath the prints, that very kimono was tucked into the box along with the obi, zori, and tabi, all rich with the scent of long years sleeping in storage. After more than 50 years, this kimono had と一緒に詰められていました。50年以上の時を越えて、この着物は日本に戻ってきたのです。私は、それを着ることで祖 returned to Japan. I was determined to carry out my grandmother’s legacy by wearing it. The only question was, how? 母の遺産を生かそうと決心しました。唯一の疑問は、どうやって?ということでした。 Subscribing to the theory of 6 degrees of separation, I knew a kimono expert couldn’t be too far away. It turns out that in 6次の隔たり(知り合いを6人辿っていくと世界中の誰とでも知り合いになれる)という仮説を当てはめると、着物の専門 Japan almost everyone knows someone who knows about kimono. I was soon introduced to Ms. Kimura, who graciously 家に辿り着くのは遠すぎるというわけではありません。日本では、ほとんど誰もが、着物について知っている誰かを知っ agreed to take me to her friend’s shop, which buys and sells kimonos secondhand. As I nestled in the shop amidst stacks ていることがわかりました。私はすぐに、木村さんという方を紹介してもらい、彼女は快く、リサイクル着物を扱ってい and stacks of carefully folded kimonos and gorgeous fabric, a new obsession was born. It was like looking at an artist’s るというお友達の店へ連れて行ってくれました。お店に入り、注意深く積まれた着物や豪華な生地の山に囲まれ、夢中に palette just waiting to be used. That day I ended up buying a secondhand furisode, still knowing nothing about how to なりました。まるで、使われるのを待っている画家のパレットを見ているようでした。その日は結局、リサイクルの振袖 actually wear the garment I was buying. -

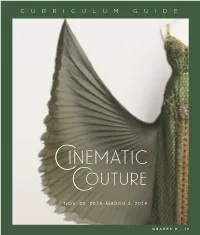

C U R R I C U L U M G U I

C U R R I C U L U M G U I D E NOV. 20, 2018–MARCH 3, 2019 GRADES 9 – 12 Inside cover: From left to right: Jenny Beavan design for Drew Barrymore in Ever After, 1998; Costume design by Jenny Beavan for Anjelica Huston in Ever After, 1998. See pages 14–15 for image credits. ABOUT THE EXHIBITION SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion + Film presents Cinematic The garments in this exhibition come from the more than Couture, an exhibition focusing on the art of costume 100,000 costumes and accessories created by the British design through the lens of movies and popular culture. costumer Cosprop. Founded in 1965 by award-winning More than 50 costumes created by the world-renowned costume designer John Bright, the company specializes London firm Cosprop deliver an intimate look at garments in costumes for film, television and theater, and employs a and millinery that set the scene, provide personality to staff of 40 experts in designing, tailoring, cutting, fitting, characters and establish authenticity in period pictures. millinery, jewelry-making and repair, dyeing and printing. Cosprop maintains an extensive library of original garments The films represented in the exhibition depict five centuries used as source material, ensuring that all productions are of history, drama, comedy and adventure through period historically accurate. costumes worn by stars such as Meryl Streep, Colin Firth, Drew Barrymore, Keira Knightley, Nicole Kidman and Kate Since 1987, when the Academy Award for Best Costume Winslet. Cinematic Couture showcases costumes from 24 Design was awarded to Bright and fellow costume designer acclaimed motion pictures, including Academy Award winners Jenny Beavan for A Room with a View, the company has and nominees Titanic, Sense and Sensibility, Out of Africa, The supplied costumes for 61 nominated films. -

Tie-Dye Shibori Mahaju E Muito Mais

tudo sobre tingimento apostila grátis degradêtie-dye shibori mahaju e muito mais corantesguarany.com.br Customize lindos óculos 14 4 Introdução 6 Por onde devo começar? 10 Tingecor 12 Vivacor Acompanhe nosso blog e redes sociais para conferir tutoriais, assistir a vídeos, tirar suas dúvidas e muito mais! 14 Sintexcor 16 Colorjeans B corantesguarany.com.br/blog 18 Fixacor facebook.com/corantesguarany 19 Tiracor Recupere seu jeans 16 20 Como misturar as cores @corantesguarany 20 Tipos de tingimento youtube.com/corantesguarany Aprenda corantesguarany.com.br o degradê 28 4 1. Introdução 5 tingimento O tingimento é uma técnica milenar que passou por diversas modificações e estudos ao longo dos anos, desde a sua forma natural, até chegar aos processos atuais de tingimento, com corantes sintéticos. Com grande poder de expressão, o mundo do tingimento abre diversas possibilidades. Este pode ser um simples reforço da cor original do tecido ou até a execução dos mais diversos tipos de técnicas aplicadas em moda, 1. decoração, artesanato, acessórios. São infinitas possibilidades. Esta apostila irá abrir as portas deste universo de cores e, para isso, foi introdução dividida em 5 etapas: identificação do tipo de fibra do tecido, quantidade de produto que deve ser utilizada, produtos para tingimento, mistura de cores e técnicas de tingimento. O objetivo é trazer inspiração para o seu dia, despertar um novo hobby, auxiliar na customização de uma peça ou, quem sabe, gerar uma opção de renda. Crie, empreenda e divirta-se! Guaranita corantesguarany.com.br 6 2. Por onde devo começar? 7 passo 1: como identificar a fibra do tecido Corte um pequeno pedaço do tecido, torça-o em forma de fio e queime-o na ponta. -

Jeanne Lanvin

JEANNE LANVIN A 01long history of success: the If one glances behind the imposing façade of Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, 22, in Paris, Lanvin fashion house is the oldest one will see a world full of history. For this is the Lanvin headquarters, the oldest couture in the world. The first creations house in the world. Founded by Jeanne Lanvin, who at the outset of her career could not by the later haute couture salon even afford to buy fabric for her creations. were simple clothes for children. Lanvin’s first contact with fashion came early in life—admittedly less out of creative passion than economic hardship. In order to help support her six younger siblings, Lanvin, then only fifteen, took a job with a tailor in the suburbs of Paris. In 1890, at twenty-seven, Lanvin took the daring leap into independence, though on a modest scale. Not far from the splendid head office of today, she rented two rooms in which, for lack of fabric, she at first made only hats. Since the severe children’s fashions of the turn of the century did not appeal to her, she tailored the clothing for her young daughter Marguerite herself: tunic dresses designed for easy movement (without tight corsets or starched collars) in colorful patterned cotton fabrics, generally adorned with elaborate smocking. The gentle Marguerite, later known as Marie-Blanche, was to become the Salon Lanvin’s first model. When walking JEANNE LANVIN on the street, other mothers asked Lanvin and her daughter from where the colorful loose dresses came. -

Title Enhanced Tradition Sub Title Author Sokol, Wilhelmine Edna

Title Enhanced tradition Sub Title Author Sokol, Wilhelmine Edna Kunze, Kai Publisher 慶應義塾大学大学院メディアデザイン研究科 Publication year 2015 Jtitle Abstract Notes Genre Thesis or Dissertation URL http://koara.lib.keio.ac.jp/xoonips/modules/xoonips/detail.php?koara_id=KO40001001-00002015 -0457 Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Master’s Thesis Academic Year 2016 Enhanced Tradition Graduate School of Media Design, Keio University Wilhelmine Edna Sokol AMaster’sThesis submitted to Graduate School of Media Design, Keio University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER of Media Design Wilhelmine Edna Sokol Thesis Committee: Associate Professor Kai Kunze (Supervisor) Professor Masahiko Inami (Co-supervisor) Professor Ichiya Nakamura (Member) Abstract of Master’s Thesis of Academic Year 2016 Enhanced Tradition Category: Design Summary Nowadays, people of this generation seem to be slowly loosing interest in tradi- tional culture of their own country. By focusing on future and possibilities o↵ered by technological advancements and following popular culture is how most people connect with each other. Tradition, expressed by both customs and objects is not something people put much thought in their everyday lives. When unification of everyday culture seems to be the leading trend, by forgetting about traditions countries, ethnic groups, etc. face the real danger of loosing their cultural iden- tity and uniqueness. While museums and galleries do wonderful job of preserving tradition, the best way to preserve it is to find a way to make it again interesting and valuable for younger generations and functional in everyday life. The purpose of this research is to establish a new path in design that combines modern interactive design with traditional wearable artifacts in a natural way.