Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cholland Masters Thesis Final Draft

Copyright By Christopher Paul Holland 2010 The Thesis committee for Christopher Paul Holland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder ___________________________________ Gail Minault Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Scholarship has tended to focus exclusively on connections of Qawwali, a north Indian devotional practice and musical genre, to religious practice. A focus on the religious degree of the occasion inadequately represents the participant’s active experience and has hindered the discussion of Qawwali in modern practice. Through the examples of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music and an insightful BBC radio article on gender inequality this thesis explores the fluid musical exchanges of information with other styles of Qawwali performances, and the unchanging nature of an oral tradition that maintains sociopolitical hierarchies and gender relations in Sufi shrine culture. Perceptions of history within shrine culture blend together with social and theological developments, long-standing interactions with society outside of the shrine environment, and an exclusion of the female body in rituals. -

A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 6-11-2009 A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau Jack Turner University of Washington Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Turner, Jack, "A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau" (2009). Literature in English, North America. 70. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/70 A Political Companion to Henr y David Thoreau POLITIcaL COMpaNIONS TO GREat AMERIcaN AUthORS Series Editor: Patrick J. Deneen, Georgetown University The Political Companions to Great American Authors series illuminates the complex political thought of the nation’s most celebrated writers from the founding era to the present. The goals of the series are to demonstrate how American political thought is understood and represented by great Ameri- can writers and to describe how our polity’s understanding of fundamental principles such as democracy, equality, freedom, toleration, and fraternity has been influenced by these canonical authors. The series features a broad spectrum of political theorists, philoso- phers, and literary critics and scholars whose work examines classic authors and seeks to explain their continuing influence on American political, social, intellectual, and cultural life. This series reappraises esteemed American authors and evaluates their writings as lasting works of art that continue to inform and guide the American democratic experiment. -

Hunston Convent and Its Reuse As Chichester Free School, 2016 - Notes by Richard D North R North- at - Fastmail.Net 25 April 2017

Hunston Convent and its reuse as Chichester Free School, 2016 - Notes by Richard D North r_north- at - fastmail.net 25 April 2017 Contents Author’s “Read Me” Hunston Convent: Building, community and school Hunston Convent (or Chichester Carmel), in a nutshell The Hunston Convent: architecture and function The Hunston Convent’s layout and the Free School Hunston Convent and other monastery building types Hunston Convent and monastic purposes Hunston Convent: From monastery to school curriculum Hunston Convent and conservation (built environment) Hunston Convent and the history curriculum Hunston Convent and the sociology curriculum Hunston Convent and the politics curriculum Hunston Convent and business studies Hunston Convent: Monasticism and a wider pastoral context Carmelites and Englishwomen and feminism Carmelites and others, and the mendicant, spiritual tradition Christian monastics and multiculturalism Christian monastics and spirituality Christian monastics and attitudes toward the world Christian monastics and usefulness Christian monastics and well-being Christian monastics and green thinking Christian monastics and hospitality Christian monastics and learning Hunston Convent and monastic suppression Hunston Convent, the Gothic, and the aesthetics of dereliction Internet research leads Document begins Author’s “Read Me” This is the latest version of a work in progress. This draft has been peer-reviewed by two senior Carmelite nuns. Please challenge the document as to fact or opinion. It’s longish: the contents table may save frustration. -

Abbess-Elect Envisions Great U. S. Benedictine Convent Mullen High to Take Day Pupils Denvircatholic Work Halted on Ten Projects

Abbess-Elect Envisions Great U. S. Benedictine Convent Mother Augustina Returns to Germany Next Month But Her Heart Will Remain in Colorado A grgantic Benedioine convent, a St. Walburga’s of ser of Eichstaett. That day is the Feast of the Holy Name In 1949 when Mother Augustina visited the German as Abbess will be as custodian and distributor of the famed the West, is the W jo c h o p e envisioned by Mother M. of Mary, a name that Mother Augustina bears as'' a nun. mother-house and conferred with the late Lady Abbess Ben- St. Walburga oil. This oil exudes from the bones of the Augustina Weihermuellcrp^perior of St. Walbutga’s con The ceremony will be held in St. Walburga’s parish church edicta, whom she has succeeejed, among the subjects con saint, who founded the Benedictine community and lived vent in South Boulder, as she prepares to return to Ger and the cloistered nuns of the community will witness it sidered wJs the possibility of transferring the heart of the 710-780. Many remarkable cures have been attributed many to assume her position as, Lady Abbess at the mother- ffom their private choir. order to America if Russia should:overrun Europe! to its use while seeking the intercession o f St. Walburga. house of her community in Eidistaett, Bavaria. That day, just two months hence, will mark the first At the great St. Walburga’s mother-house in Eich 'Those who have heard Mother Augustina in one of her Mother Augustina’s departure for Europe is scheduled time that an American citizen ,has returned to Europe to staett, she will be superior of 130 sisters. -

Christian Monastic Communities Living in Harmony with the Environment: an Overview of Positive Trends and Best Practices 1

Christian monastic communities living in harmony with the environment: an overview of positive trends and best practices 1 Abstract This paper explores the relationship between Christian monastic communities and nature and the natural environment, a new field for this journal. After reviewing their historical origins and evolution, and discussing their key doctrinal principles regarding the environment, the paper provides an overview of the best practices developed by these communities of various sizes that live in natural surroundings, and reviews promising new trends. These monastic communities are the oldest self-organised communities in the Old World with a continuous history of land and environmental management, and have generally had a positive impact on nature and landscape conservation. Their experience in adapting to and overcoming environmental and economic crises is highly relevant in modern-day society as a whole and for environmental managers and policy makers in particular. This paper also argues that the efforts made by a number of monastic communities, based on the principles of their spiritual traditions, to become more environmentally coherent should be encouraged and publicized to stimulate more monastic communities to follow their example and thus to recapture the environmental and spiritual coherence of their ancestors. The paper concludes that the best practices in nature conservation developed by Christian 1 This paper is a substantial development, both in content and scope, of a previous paper written by one of us (JM) for the Proceedings of the Third workshop of The Delos Initiative, which took place in Lapland, Finland, in 2010. A certain number of the experiences discussed here comes from case studies prepared during the last nine years in the context of The Delos Initiative, jointly co-ordinated by two of us (TP, JM), within the IUCN World Commission of Protected Areas. -

Monasticism Old And

Study Guides for Monasticism Old and New These guides integrate Bible study, prayer, and worship to explore how monastic communities, classic and new, provide a powerful critique of mainstream culture and offer transforming possibilities Christian Reflection for our discipleship. Use them individually or in a series. You may A Series in Faith and Ethics reproduce them for personal or group use. A Vision So Old It Looks New 2 It is hard to be a Christian in America today. But that can be good news, the new monastics are discovering. If the cost of discipleship pushes us to go back and listen to Jesus again, it may open us to costly grace and the transformative power of resurrection life. In every era God has raised up new monas- tics to remind the Church of its true vocation. The Finkenwalde Project 4 Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s project at Finkenwalde Seminary to recover for congregations the deep Christian tradition is a prominent model for young twenty-first-century Christians. Weary of the false dichotomy between right belief and right practice, they seek the wholeness of discipleship in what Bonhoeffer called “a kind of new monasticism.” Evangelicals and Monastics 6 Could any two groups of Christians—evangelicals and monastics—be more different? But the New Monasticism movement has opened a new chapter in the relations of these previously estranged groups. Nothing is more characteristic of monastics and evangelicals than their unshakable belief that one cannot be truly spiritual without putting one’s faith into practice, and one cannot sustain Christian discipleship without a prayerful spirituality. -

Temperance in the Modern World

Temperance in the modern world In Pope Francis’ continuing diagnosis of the world’s ills, elaborated on thoroughly in his most recent encyclical Laudato Si‘ (On Care for Our Common Home), consumerism — excess consumption of material goods — ranks consistently at or near the top of the list. Consumerism is one face of the maldistribution of wealth, the other face of which is poverty. The pope calls it a “poison” that reflects “emptiness of meaning and values.” Collective consumerism is among the symptoms of what Pope St. John Paul II called “superdevelopment.” This aberration, he explained, arises from “excessive availability of every kind of material goods, for the benefit of certain social groups” and is expressed in an obsessive quest to own and consume more and more (Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, No. 28). The cure for this disease of the spirit, considered as a social problem, is the practice of social justice in economic policies, practices and laws. On the individual level, too, each of us is tempted to consumerism and has social justice responsibilities. But how are ordinary people to practice social justice? The answer is temperance. Cumulatively, temperance can make a real contribution to social justice. One person living temperately gives a good example. A multitude living temperately can change a nation, or even the world, for the better. Pope Francis makes much the same point in his encyclical, Laudato Si‘, where he uses the word “sobriety” to describe an attitude equivalent to temperance. Living this way, he writes, means “living life to the full … learning familiarity with the simplest things and how to enjoy them” (No. -

Kenosis and the Nature of the Persons in the Trinity

Kenosis and the nature of the Persons in the Trinity David T. Williams Department of Historical and Contextual Theology University of Fort Hare ALICE E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Kenosis and the nature of the Persons in the Trinity Philippians 2:7 describes the kenosis of Christ, that is Christ’s free choice to limit himself for the sake of human salvation. Although the idea of Christ’s kenosis as an explanation of the incarnation has generated considerable controversy and has largely been rejected in its original form, it is clear that in this process Christ did humble himself. This view is consistent with some contemporary perspectives on God’s self-limitation; in particular as this view provides a justification for human freedom of choice. As kenosis implies a freely chosen action of God, and not an inherent and temporary limitation, kenosis is consistent with an affirmation of God’s sovereignty. This view is particularly true if Christ’s kenosis is seen as a limitation of action and not of his attributes. Such an idea does not present problems concerning the doctrine of the Trinity, specifically regarding the relation between the economic and the immanent nature of the Trinity. The Trinitarian doctrine, on the contrary, indeed complements this idea – specifically the concept of perichoresis (the inter- relatedness among the Persons of the Triniy and the relation between the two natures of Christ). Opsomming Kenosis en die aard van die Persone in die Drie-eenheid Filippense 2:7 beskryf die kenosis van Christus – sy vrye keuse om homself te ontledig ter wille van die mens se verlossing. -

Mysticism and Mystical Experiences

1 Mysticism and Mystical Experiences The first issue is simply to identify what mysti cism is. The term derives from the Latin word “mysticus” and ultimately from the Greek “mustikos.”1 The Greek root muo“ ” means “to close or conceal” and hence “hidden.”2 The word came to mean “silent” or “secret,” i.e., doctrines and rituals that should not be revealed to the uninitiated. The adjec tive “mystical” entered the Christian lexicon in the second century when it was adapted by theolo- gians to refer, not to inexpressible experiences of God, but to the mystery of “the divine” in liturgical matters, such as the invisible God being present in sacraments and to the hidden meaning of scriptural passages, i.e., how Christ was actually being referred to in Old Testament passages ostensibly about other things. Thus, theologians spoke of mystical theology and the mystical meaning of the Bible. But at least after the third-century Egyptian theolo- gian Origen, “mystical” could also refer to a contemplative, direct appre- hension of God. The nouns “mystic” and “mysticism” were only invented in the seven teenth century when spirituality was becoming separated from general theology.3 In the modern era, mystical inter pretations of the Bible dropped away in favor of literal readings. At that time, modernity’s focus on the individual also arose. Religion began to become privatized in terms of the primacy of individuals, their beliefs, and their experiences rather than being seen in terms of rituals and institutions. “Religious experiences” also became a distinct category as scholars beginning in Germany tried, in light of science, to find a distinct experi ential element to religion. -

The Motive of Asceticism in Emily Dickenson's Poetry

International Academy Journal Web of Scholar ISSN 2518-167X PHILOLOGY THE MOTIVE OF ASCETICISM IN EMILY DICKENSON’S POETRY Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid, Ph.D. Odlar Yurdu University, Baku, Azerbaijan DOI: https://doi.org/10.31435/rsglobal_wos/31012020/6880 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: 25 November 2019 This paper is an attempt to analyze the poetry of Miss Emily Dickinson Accepted: 12 January 2020 (1830-1886) contributed both American and World literature in order to Published: 31 January 2020 reveal the extent of asceticism in it. Asceticism involves a deep, almost obsessive, concern with such problems as death, the life after death, the KEYWORDS existence of the soul, immortality, the existence of God and heaven, the meaningless of life and etc. Her enthusiastic expressions of life in poems spiritual asceticism, psychological had influenced the development of poetry and became the source of portrait, transcendentalism, Emily inspiration for other poets and poetesses not only in last century but also . Dickenson’s poetry in modern times. The paper clarifies the motives of spiritual asceticism, self-identity in Emily Dickenson’s poetry. Citation: Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid. (2020) The Motive of Asceticism in Emily Dickenson’s Poetry. International Academy Journal Web of Scholar. 1(43). doi: 10.31435/rsglobal_wos/31012020/6880 Copyright: © 2020 Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. -

The Importance of Athanasius and the Views of His Character

The Importance of Athanasius and the Views of His Character J. Steven Davis Submitted to Dr. Jerry Sutton School of Divinity Liberty University September 19, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I: Research Proposal Abstract .............................................................................................................................11 Background ......................................................................................................................11 Limitations ........................................................................................................................18 Method of Research .........................................................................................................19 Thesis Statement ..............................................................................................................21 Outline ...............................................................................................................................21 Bibliography .....................................................................................................................27 Chapter II: Background of Athanasius An Influential Figure .......................................................................................................33 Early Life ..........................................................................................................................33 Arian Conflict ...................................................................................................................36 -

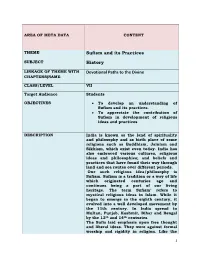

Sufism and Its Practices History Devotional Paths to the Divine

AREA OF META DATA CONTENT THEME Sufism and its Practices SUBJECT History LINKAGE OF THEME WITH Devotional Paths to the Divine CHAPTERS(NAME CLASS/LEVEL VII Target Audience Students OBJECTIVES To develop an understanding of Sufism and its practices. To appreciate the contribution of Sufism in development of religious ideas and practices DESCRIPTION India is known as the land of spirituality and philosophy and as birth place of some religions such as Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism, which exist even today. India has also embraced various cultures, religious ideas and philosophies; and beliefs and practices that have found their way through land and sea routes over different periods. One such religious idea/philosophy is Sufism. Sufism is a tradition or a way of life which originated centuries ago and continues being a part of our living heritage. The term Sufism’ refers to mystical religious ideas in Islam. While it began to emerge in the eighth century, it evolved into a well developed movement by the 11th century. In India spread to Multan, Punjab, Kashmir, Bihar and Bengal by the 13th and 14th centuries. The Sufis laid emphasis upon free thought and liberal ideas. They were against formal worship and rigidity in religion. Like the 1 Bhakti saints, the Sufis too interpreted religion as ‘love of god’ and service of humanity. Sufis believe that there is only one God and that all people are the children of God. They also believe that to love one’s fellow men is to love God and that different religions are different ways to reach God.