Of the History of Jews in Silesia ISBN 978-83-939143-1-9 Bits of the History of Jews in Silesia Bits of History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

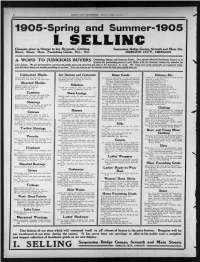

Suspension Bridge Corner, Seventh and Main Streets 3 I-- ' O LL G OREGON CITY, OREGON

OREGON CITY ENTERPRISE, FRIDAY, APRIL 14, l!0o. (LflDTmOTTD On , Cheapest place in Oregon to buy Dry-goods- Clothing, Suspension Bridge Corner, Seventh and Main Sts. Boots, Shoes, Hats, Furnishing Goods, Etc., Etc. OREGON CITY, OREGON A. "WORD JUDICIOUS ' BUYERS Conccyning Spring and Summer Goods. Out special effort for the Spring Season is to TO increase the purchasing power of yof Dollar with the Greatest values ever afforded for your money." We are determined to convince the public more and more that out store is the best place to trade. We want yoar trade constantly and regularly when- ever the future finds you needing anything in out tine. Yog can always get the lowest prices for first class goods from ts Unbleached Muslin Art Denims and Cretonnes Dress Goods Notions, Etc. 36 inch wide, best LL, per yard, 5c. Art denims, 36 inch wide, per yard, 15e. Our line of dress goods for the Spring and Clark's O. N. T. spool cotton, 6 spools for 25o 36 inch wide, best Cabot W, per yard, 6y2c. Cretonnes, figured, oil finish, per yard, 8c. Summer of 1905 is a wonderful collection San silk, 2 spools for 5c. ' Twilled heavy, per yard, 10c. of elegant designs and fabrics of the newest Bone crochet hooks, 2 for 5c. Bleached Muslins and most popular fashions for the coming Knitting needles, set, 5c. season. Prices are uniformly low. Besf Eagle pins, 5c paper. Common quality, per yard, 5c. Silkoline 34 inch wide cashmere per yard 15c. Embroidery silk, 3 skeins for 10c. Medium grade, per yard, 7c. -

Breslau Or Wrocław? the Identity of the City in Regards to the World War II in an Autobiographical Reflection

DEBATER A EUROPA Periódico do CIEDA e do CEIS20 , em parceria com GPE e a RCE. N.13 julho/dezembro 2015 – Semestral ISSN 1647-6336 Disponível em: http://www.europe-direct-aveiro.aeva.eu/debatereuropa/ Breslau or Wrocław? The identity of the city in regards to the World War II in an autobiographical reflection Anna Olchówka University of Wrocław E-mail: [email protected] Abstract On the 1st September 1939 a German city Breslau was found 40 kilometers from the border with Poland and the first front lines. Nearly six years later, controlled by the Soviets, the city came under the "Polish administration" in the "Recovered Territories". The new authorities from the beginning virtually denied all the past of the city, began the exchange of population and the gradual erasure of multicultural memory; the heritage of the past recovery continues today. The main objective of this paper is to present the complexity of history through episodes of a city history. The analysis of texts and images, biographies of the inhabitants / immigrants / exiles of Breslau / Wrocław and the results of modern research facilitate the creation of a complex political, economic, social and cultural landscape, rewritten by historical events and resettlement actions. Keywords: Wrocław; Breslau; identity; biography; history Scientific meetings and conferences open academics to new perspectives and face them against different opinions, arguments, works and experiences. The last category, due to its personal and individual aspect, is very special. Experience can be shared and gained at the same time, which is inherent to the continuous development of human beings. Because of its subjectivity, experiences often pose a great methodological problem for the humanistic studies. -

The British Linen Trade with the United States in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 1990 The British Linen Trade With The United States In The Eighteenth And Nineteenth Centuries N.B. Harte University College London Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Harte, N.B., "The British Linen Trade With The United States In The Eighteenth And Nineteenth Centuries" (1990). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 605. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/605 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. -14- THE BRITISH LINEN TRADE WITH THE UNITED STATES IN THE EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES by N.B. HARTE Department of History Pasold Research Fund University College London London School of Economics Gower Street Houghton Street London WC1E 6BT London WC2A 2AE In the eighteenth century, a great deal of linen was produced in the American colonies. Virtually every farming family spun and wove linen cloth for its own consumption. The production of linen was the most widespread industrial activity in America during the colonial period. Yet at the same time, large amounts of linen were imported from across the Atlantic into the American colonies. Linen was the most important commodity entering into the American trade. This apparently paradoxical situation reflects the importance in pre-industrial society of the production and consumption of the extensive range of types of fabrics grouped together as 'linen*. -

Conquering the Conqueror at Belgrade (1456) and Rhodes (1480

Conquering the conqueror at Belgrade (1456) and Rhodes (1480): irregular soldiers for an uncommon defense Autor(es): De Vries, Kelly Publicado por: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/41538 DOI: DOI:https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-8925_30_13 Accessed : 5-Oct-2021 13:38:47 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. impactum.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt Kelly DeVries Revista de Historia das Ideias Vol. 30 (2009) CONQUERING THE CONQUEROR AT BELGRADE (1456) AND RHODES (1480): IRREGULAR SOLDIERS FOR AN UNCOMMON DEFENSE(1) Describing Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II's military goals in the mid- -fifteenth century, contemporary Ibn Kemal writes: "Like the world-illuminating sun he succumbed to the desire for world conquest and it was his plan to burn with overpowering fire the agricultural lands of the rebellious rulers who were in the provinces of the land of Rüm [the Byzantine Empire!. -

Gmina Prudnik Położona Jest W Południowej Części Województwa Opolskiego, Graniczy Z Republiką Czeską

Prudnik miasto z wizją Położenie Gmina Prudnik położona jest w południowej części województwa opolskiego, graniczy z Republiką Czeską. Przez gminę prowadzi szlak komunikacyjny z północy Europy na jej południe. Prudnik jest bardzo dobrze skomunikowany poprzez siec dróg krajowych z autostradą A4 oraz z siecią dróg międzynarodowych między innymi Czech i Słowacji. Gminę zamieszkuje 27 500 mieszkańców, znanych ze swej pracowitości i uczciwości. Miasto dzięki swojemu położeniu jest „bramą” na południe Europy, miejscem z którego jest blisko do aglomeracji w Polsce oraz południa Europy. Największe miasta, porty lotnicze Litwa Białoruś BERLIN Niemcy LEGENDA inwestycje ukończone lub w trakcie realizacji nowe inwestycje ujęte w planie 2014-2023 nowe planowane inwestycje PRAGA PRUDNIK Czechy OSTRAVA Ukraina Słowacja . odległość z Prudnika . odległość z Prudnika . do większych miast . do największych portów lotniczych . Opole 50 km . Ostrawa 95 km Wrocław 115 km . Wrocław 115 km . Katowice 125 km . Katowice 125 km Kraków 200 km . Kraków 200 km Praga 280 km . Warszawa 380 km . Warszawa 380 km . Berlin 450 km . Oferta inwestycyjna Wałbrzyska Specjalna Strefa Ekonomiczna – Podstrefa Prudnik Tereny niezabudowane - ul.Przemysłowa 10 Tereny zabudowane - ul.Nyska 13469.85 m2 Pomoc dla inwestorów Prowadząc działalność gospodarczą na terenie Wałbrzyskiej Specjalnej Strefy Ekonomicznej, przedsiębiorca otrzymuje pomoc publiczną w postaci ulg podatkowych (zwolnienie z podatku dochodowego CIT lub PIT w zależności od formy prowadzenia działalności). WIELKOŚĆ WOJEWÓDZTWO WOJEWÓDZTWO LUBUSKIE DOLNOŚLĄSKIE FIRMY I OPOLSKIE I WIELKOPOLSKIE do do 35% 25% kosztów DUŻE inwestycji ulga w podatku lub do do dochodowym 2-letnich 45% 35% kosztów CIT ŚREDNIE zatrudnienia lub nowych do do PIT 55% 45% pracowników MAŁE I MIKRO źródło: https://invest-park.com.pl/dla-inwestora/ulgi-podatkowe-pomoc-publiczna/ Gmina Prudnik posiada program pomocy de minimis dla przedsiębiorców tworzących nowe miejsca pracy w związku z nową inwestycją. -

Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe New Perspectives on Modern Jewish History

Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe New Perspectives on Modern Jewish History Edited by Cornelia Wilhelm Volume 8 Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe Shared and Comparative Histories Edited by Tobias Grill An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISBN 978-3-11-048937-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049248-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-048977-4 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Grill, Tobias. Title: Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe : shared and comparative histories / edited by/herausgegeben von Tobias Grill. Description: [Berlin] : De Gruyter, [2018] | Series: New perspectives on modern Jewish history ; Band/Volume 8 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018019752 (print) | LCCN 2018019939 (ebook) | ISBN 9783110492484 (electronic Portable Document Format (pdf)) | ISBN 9783110489378 (hardback) | ISBN 9783110489774 (e-book epub) | ISBN 9783110492484 (e-book pdf) Subjects: LCSH: Jews--Europe, Eastern--History. | Germans--Europe, Eastern--History. | Yiddish language--Europe, Eastern--History. | Europe, Eastern--Ethnic relations. | BISAC: HISTORY / Jewish. | HISTORY / Europe / Eastern. Classification: LCC DS135.E82 (ebook) | LCC DS135.E82 J495 2018 (print) | DDC 947/.000431--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018019752 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. -

John of Capistrano

John of Capistrano “Capistrano” redirects here. For other uses, see Capistrano (disambiguation). Saint John of Capistrano (Italian: San Giovanni Painting in St. John of Capistrano Church in Ilok, Croatia, where he was buried 1 Early life Statue of John of Capistrano in Budapest, Hungary As was the custom of this time, John is denoted by the da Capestrano, Slovenian: Janez Kapistran, Hungarian: village of Capestrano, in the Diocese of Sulmona, in the Kapisztrán János, Polish: Jan Kapistran, Croatian: Ivan Abruzzi region, Kingdom of Naples. His father had come Kapistran, Serbian: Јован Капистран, Jovan Kapis- to Italy with the Angevin court of Louis I of Anjou, tit- tran) (June 24, 1386 – October 23, 1456) was a ular King of Naples. He studied law at the University of Franciscan friar and Catholic priest from the Italian town Perugia. [1] of Capestrano, Abruzzo. Famous as a preacher, theolo- In 1412, King Ladislaus of Naples appointed him Gov- gian, and inquisitor, he earned himself the nickname 'the ernor of Perugia, a tumultuous and resentful papal fief Soldier Saint' when in 1456 at age 70 he led a crusade held by Ladislas as the pope’s champion, in order to ef- against the invading Ottoman Empire at the siege of Bel- fectively establish public order. When war broke out be- grade with the Hungarian military commander John Hun- tween Perugia and the Malatestas in 1416, John was sent yadi. as ambassador to broker a peace, but Malatesta threw him Elevated to sainthood, he is the patron saint of jurists and in prison. During the captivity, in despair he put aside military chaplains, as well as the namesake of the Francis- his new young wife, never having consummated the mar- can missions San Juan Capistrano in Southern California riage, and started studying theology with Bernardino of and San Juan Capistrano in San Antonio, Texas. -

Selected City Gates in Silesia – Research Issues1 Wybrane Zespoły Bramne Na Śląsku – Problematyka Badawcza

TECHNICAL TRANSACTIONS 3/2019 ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN PLANNING DOI: 10.4467/2353737XCT.19.032.10206 SUBMISSION OF THE FINAL VERSION: 15/02/2019 Andrzej Legendziewicz orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-296X [email protected] Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Technology Selected City Gates in Silesia – research issues1 Wybrane zespoły bramne na Śląsku – problematyka badawcza Abstract1 The conservation work performed on the city gates of some Silesian cities in recent years has offered the opportunity to undertake architectural research. The researchers’ interest was particularly aroused by towers which form the framing of entrances to old-town areas and which are also a reflection of the ambitious aspirations and changing tastes of townspeople and a result of the evolution of architectural forms. Some of the gate buildings were demolished in the 19th century as a result of city development. This article presents the results of research into selected city gates: Grobnicka Gate in Głubczyce, Górna Gate in Głuchołazy, Lewińska Gate in Grodków, Krakowska and Wrocławska Gates in Namysłów, and Dolna Gate in Prudnik. The obtained research material supported an attempt to verify the propositions published in literature concerning the evolution of military buildings in Silesia between the 14th century and the beginning of the 17th century. Relicts of objects that have not survived were identified in two cases. Keywords: Silesia, architecture, city walls, Gothic, the Renaissance Streszczenie Prace konserwatorskie prowadzone na bramach w niektórych miastach Śląska w ostatnich latach były okazją do przeprowadzenia badań architektonicznych. Zainteresowanie badaczy budziły zwłaszcza wieże, które tworzyły wejścia na obszary staromiejskie, a także były obrazem ambitnych aspiracji i zmieniających się gustów mieszczan oraz rezultatem ewolucji form architektonicznych. -

HT Rozdzial 3 Pressto.Indd

ISSN 2450-8047 nr 2016/1 (1) http://dx.doi.org/10.14746/ht.2016.1.1.04 s. 43-71 TRANSFORMATIONS IN THE POLISH-GERMAN-CZECH BORDER AREA IN 1938-1945 IN THE LOCAL COLLECTIVE MEMORY AND SOCIAL AWARENESS OF THE INHABITANTS OF BIELAWA AND THE OWL MOUNTAINS AREA Jaromir JESZKE Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan ABSTRACT Th e local community of Bielawa and the areas in the region of the Owl Mountains is an inter- esting object for studies of sites of memory represented in local consciousness. Like most of similar communities on the so-called Recovered Territories, it started to form aft er 1945 on “raw roots” aft er the German inhabitants of the area were removed. Th ey were replaced with people moved from the former eastern provinces of the Second Republic, among others from Kołomyja, but also from regions of central Poland. Also Poles returning from Germany, France and Romania sett led there. Th e area taken over by new sett lers had not been a cultural desert. Th e remains of material culture, mainly German, and the traditions of weaving and textile industry, reaching back to the Middle Ages, formed a huge potential for creating a vision of local cultural heritage for the newly forming community. Th ey also brought, however, their own notions of cultural heritage to the new area and, in addition, became subject to political pressure of recognising its “Piast” character as the “Recovered Territories”. Th e present re- search is an att empt to fi nd out to what extent that potential was utilised by new sett lers, who were carriers of various regional (or even national) cultures, for their creation of visions of the future, as well as how the dynamics of those transformations evolved. -

Wrocław Główny - Legnica - Chojnów - Bolesławiec - Węgliniec - Lubań Śląski

D1 Wrocław Główny - Legnica - Chojnów - Bolesławiec - Węgliniec - Lubań Śląski Zastępcza Komunikacja Autobusowa na odcinku Węgliniec - Lubań Śląski (23-30.06.2021) Rozkład jazdy obowiązuje od 13.06.2021 do 28.08.2021 Rozkład jazdy może ulec zmianie, aktualne informacje dostępne są w wyszukiwarkach połączeń oraz pod adresem www.kolejedolnoslaskie.pl przewoźnik KD KD KD KD KD KD KDKD KD KD KD KD KD KD KD KD KD KD 69228 69551 69228 69553/2 67001 66557 69161 69504 66559 69555 69557/6 69559 69163 69561 66561 69165 69563/2 69565 numer pociągu 5300 5842 numer linii D1 D10 D1 D1 D25 D11 D10 D1 D11 D1 D1 D1 D11 D10 D11 D10 D1 D10 SB-ND PN-PT PN-PT SB-ND PN-PT SB-ND KD Sprinter KD Sprinter KD Sprinter nazwa pociągu Telemann Tadeusz Łużyce Nysa Zastawnik [21] [22] [24] [23] [23] [24] [23] [25] [26] [30] [28] [29] [27] [96] [87] [81] [82] [23] [24] Jelcz- Jelcz- km ze stacji -Laskowice -Laskowice 0,000 Wrocław Główny o ) 04.35 ) 04.35 ) 05.05 05.43 06.10 ) 06.45 07.20 ) 07.53 ) 07.53 ) 08.03 ) 08.20 ) 08.20 ) 08.20 ) 08.20 ) 08.55 ) 09.01 09.54 10.20 ) 10.56 ) 10.58 ) 11.45 ) 11.45 12.36 4,956 Wrocław Muchobór ) 04.44 ) 04.44 ) 05.11 05.49 06.16 ) 06.50 07.29 ) 08.01 ) 08.01 ) 08.11 ) 08.26 ) 08.26 ) 08.29 ) 08.29 ) 09.01 ) 09.07 10.00 10.26 ) 11.10 ) 11.04 ) 11.50 ) 11.50 12.42 6,812 Wrocław Nowy Dwór ) 04.47 ) 04.47 ) 05.14 05.52 06.19 ) 06.53 07.33 ) 08.04 ) 08.04 ) 08.15 ) 08.29 ) 08.29 ) 08.33 ) 08.33 ) 09.04 ) 09.10 10.03 10.28 ) 11.14 ) 11.07 ) 11.53 ) 11.53 12.45 9,495 Wrocław Żerniki ) 04.50 ) 04.50 | 05.55 | ) 06.55 07.36 ) 08.07 ) 08.07 -

Prudnicki.Pl Internet: PRUDNICKI Już Od GAZETA LOKALNA GMIN: PRUDNIK • BIAŁA • GŁOGÓWEK * KORFANTÓW • LUBRZA * STRZELECZKI * WALCE Prudnik, Ul

Nr 31 (766) 3 sierpnia 2005 r. Cena 1,70 zł (w tym 0% VAT) DRZWI WEWNĘTRZNE CLAS&h Rok XVI ISSN 1231 ■ 904 X TYGODNIK Indeks 327816 wydaje: Aneks telefax: 4362877 nowe wzór tel.: 4369174 e-mail: [email protected] internet: www.aneks.com.pl/tp PRUDNICKI już od GAZETA LOKALNA GMIN: PRUDNIK • BIAŁA • GŁOGÓWEK * KORFANTÓW • LUBRZA * STRZELECZKI * WALCE Prudnik, ul. Powstańców Śląskich 2 • tel. 436 09 66 Głuchołazy, ul. Prymasa Wyszyńskiego 9a • tel. 439 2184 Okręgowa Spółdzielnia Mleczarska w Prudniku JAK BARDZO ZADŁUŻONA JEST GIMNA PRUDNIK? FIRMA 2004 ROKU Mówi się, że wszelkie Głosami czytelników Tygodnika Prudnickiego i członków Kapituły Wieży Woka to prestiżowe prace remontowe wyróżnienie trafi do OSM Prudnik. W tym numerze przybliżamy firmę w statystyce, str. 78 i inwestycje w gminie osiągnięciach oraz w rozmowie z prezesem Ryszardem Witkiem. są wynikiem coraz Dachował większego zadłużenia. Jak to wygląda na nieużywanej w konkretnych liczbach? drodze W piątek, 22 lipca późnynym BURZA wieczorem doszło do wypad NAD POWIATEM ku na starej, „ślepej” drodze między Prudnikiem a Niemysłowicami. Dachował Opel Omega. Nie znamy okoliczności tego zdarzenia. Od mieszkańca Niemysłowic dowiedzieliśmy się, że ten fragment drogi służy do popisów „kaskaderskich” bardziej krewkich kierowców. AD W nocy z soboty na niedzielę zgodnie z prognozą pogody przez Polskę przeszedł front Zarejestrował atmosferyczny. Efektów jego działania firmę doświadczyliśmy także w powiecie prudnickim. w pół godziny W niektórych wsiach, czy dzielnicach miast brak było prądu, powalonych zostało kilka drzew. Dobrze, że obyło się bez ofiar w ludziach. Nie było też znacznych strat materialnych, jakich można by się spodziewać po tak f ł W J TO I i dfe silnych nocnych 1 ł bpi 8 burzach. -

Powiat M. Legnica W Statystyce 2002-2005

URZĄD STATYSTYCZNY WE WROCŁAWIU POWIAT M. LEGNICA W STATYSTYCE 2002-2005 POWIATY I GMINY W STATYSTYCE BANK DANYCH REGIONALNYCH JAKO ŹRÓDŁO INFORMACJI STATYSTYCZNYCH WROCŁAW 2006 POWIAT I GMINY W STATYSTYCE POWIAT M. LEGNICA W WOJEWÓDZTWIE - środowisko - ludność - infrastruktura społeczna i techniczna - przedsiębiorczość - budżet gmin - planowanie przestrzenne RANKINGI GMIN WOJ. DOLNOŚLĄSKIEGO W GRAFICE - odsetek użytków rolnych - przyrost naturalny na 1000 ludności - odsetek mieszkań stanowiących własność gminy - podmioty gospodarcze na 1000 ludności - dochody budżetu gminy na 1 mieszkańca WYKAZ JEDNOSTEK PODZIAŁU TERYTORIALNEGO W WOJ. DOLNOŚLĄSKIM Użytki rolne w % powierzchni gminy w 2002 roku Użytki rolne w % powierzchni gminy w 2002 roku - klasyfikacja gmin Czarny Bór Oława m. gminy miejskie Stara Kamienica gminy miejsko-wiejskie Pieńsk gminy wiejskie Prochowice Jelcz-Laskowice Rudna Twardogóra Bielawa Przemków Żmigród Niechlów Lądek-Zdrój Platerówka Gaworzyce Wrocław Wleń Paszowice Dzierżoniów w. Bardo Kamienna Góra m. Wąsosz Radwanice Domaniów Boguszów-Gorce Cieszków Lwówek Śląski Złotoryja w. Ruja Jedlina-Zdrój Lubin m. Nowogrodziec Żarów Mściwojów Chojnów m. Marciszów Jerzmanowa Malczyce Kostomłoty Bogatynia Kotla Czernica Warta Bolesławiecka Strzegom Żórawina Polkowice Walim Męcinka Kunice Przeworno Borów Bolesławiec w. Oborniki Śląskie Świerzawa Bierutów Dziadowa Kłoda Kobierzyce Świdnica m. Janowice Wielkie Bolków Lubań w. Ścinawa Udanin Milicz Nowa Ruda w. Stare Bogaczowice Mietków Sulików Wądroże Wielkie Świeradów-Zdrój Brzeg Dolny Jeżów Sudecki Sobótka Środa Śląska Jordanów Śląski Chocianów Lubin w. Głogów w. Świebodzice Trzebnica Zagrodno Zgorzelec m. Wołów Kłodzko m. Jawor Łagiewniki Wiązów Jelenia Góra Lubawka Gryfów Śląski Oława w. Miłkowice Legnickie Pole Kudowa-Zdrój Pieszyce Lubomierz Olszyna Siekierczyn Ząbkowice Śląskie Duszniki-Zdrój Wojcieszów Krośnice Oleśnica m. Świdnica w. Pielgrzymka Kondratowice Polanica-Zdrój Głuszyca Międzybórz Stoszowice Chojnów w.