Ariel 36(1-2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remember to Have a Page Before the Title Page with Title and Name

“This place being South Africa”: Reading race, sex and power in J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace by Kimberly Chou “This place being South Africa”: Reading race, sex and power in J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace by Kimberly Chou A thesis presented for the B.A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Spring 2009 © Kimberly Chou 16 March 2009 For fellow readers who have picked up this deeply provocative novel and found themselves at its close with more questions than answers—and for those who have yet to join the conversation. Acknowledgements I am indebted to my advisor, Jennifer Wenzel, for her guidance, patience and forthright criticism. Thank you for challenging me to challenge myself, and for sharing great appreciation for the work of J.M. Coetzee and, most importantly, a love of South Africa. Thank you to Cathy Sanok and Andrea Zemgulys, for unwavering support throughout the thesis-writing process. Thank you to the 2009 English honors thesis cohort for creating a space of encouragement and commiseration. Thank you to the peers and professors at the University of Cape Town who influenced early development of this project. A special thank you to Obs Books in Observatory, Cape Town. Thank you to my family and friends, who have, at this point, likely heard more about the ethics of reading and the politics of place than they had ever wished. Sincere thanks to M.M., F.R., E.M. and J.N. for their honesty and advice. Abstract Whatever discourse J.M. Coetzee intended to arouse with Disgrace, his 1999 novel that addresses changing social dynamics in post-apartheid South Africa, the conversation it has inspired since its publication has been dominated by readers’ suspicions. -

Summertime (David Attwell)

Trauma, Memory and Narrative in the Contemporary South African Novel Abstracts “ To speak of this you would need the tongue of a god” : On Representing the Trauma of Township Violence (Derek Attridge) It is winter, 1986, on the Cape Flats, and the elderly white lady finds that she cannot produce words equal to the horror of the scene she is witnessing in the shantytown, where the shacks of the inhabitants are being burned by vigilantes. In J. M. Coetzee’s 1990 novel Age of Iron, the author himself does, of course, describe the scene, reflecting in his choice of language Mrs Curren’s familiarity with classical literature and its accounts of traumatic events. It is an outsider’s description, evincing bafflement as well as shock. For what we are invited to read as an insider’s description of a similar scene occurring ten years earlier, we can turn to The Long Journey of Poppie Nongena, Elsa Joubert’s transcription/rewriting of a black woman’s experiences as narrated to her over a twoyear period and first published in Afrikaans in 1978. This paper will compare the narrative strategies of the two authors in attempting to represent the trauma of township violence – marked not just by savage actions but by confusion as to who is friend and who is enemy – and consider the theoretical implications of their choices. Trauma Refracted: J.M. Coetzee’s Summertime (David Attwell) J.M. Coetzee’s Summertime completes a cycle of autobiographical fictions which begins with Boyhood and continues with Youth. In the third and most recent of these works, the protagonist begins publishing his early fiction. -

Age of Iron in the Heart of the Cou1ttry Waiting for the Ba.Rbcm'ans Life & Times of Michael K Foe J.M

By th.e same author • • Dusklands Age of Iron In the Heart of the Cou1ttry Waiting for the Ba.rbcm'ans Life & Times of Michael K Foe J.M. COETZ,EE Seeker & Warburg London By th.e same author • • Dusklands Age of Iron In the Heart of the Cou1ttry Waiting for the Ba.rbcm'ans Life & Times of Michael K Foe J.M. COETZ,EE Seeker & Warburg London First published in Great Britain in 1990 For by Martin Seeker & Warburg Limited Michelin House, 81 .Fulham Road, London SWJ 6RB V.H.M..C. (1904-1985) z.c. (1912-1988) Copyright© 1990].. M. Coetzee N.G.C. (1966-1989) A CIP catalogue r'ecord for this book is availabl'e from the British Library ISBN 0 43,6 20012 0 Photoset by Rowland Phototypesetting Limited Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk Printed in Great Britain by Richard Clay Limited, Bungay,, Suffolk First published in Great Britain in 1990 For by Martin Seeker & Warburg Limited Michelin House, 81 .Fulham Road, London SWJ 6RB V.H.M..C. (1904-1985) z.c. (1912-1988) Copyright© 1990].. M. Coetzee N.G.C. (1966-1989) A CIP catalogue r'ecord for this book is availabl'e from the British Library ISBN 0 43,6 20012 0 Photoset by Rowland Phototypesetting Limited Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk Printed in Great Britain by Richard Clay Limited, Bungay,, Suffolk T-here is an alley down the side of the garage, you may remember it, you and your friends would sometimes play ther,e. Now it is a dead place, waste, without use, where windblown leaves pi'fe up and rot. -

Coetzee's Stones: Dusklands and the Nonhuman Witness

Safundi The Journal of South African and American Studies ISSN: 1753-3171 (Print) 1543-1304 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsaf20 Coetzee’s stones: Dusklands and the nonhuman witness Daniel Williams To cite this article: Daniel Williams (2018): Coetzee’s stones: Dusklands and the nonhuman witness, Safundi, DOI: 10.1080/17533171.2018.1472829 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17533171.2018.1472829 Published online: 21 Jun 2018. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsaf20 SAFUNDI: THE JOURNAL OF SOUTH AFRICAN AND AMERICAN STUDIES, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1080/17533171.2018.1472829 Coetzee’s stones: Dusklands and the nonhuman witness Daniel Williams Society of Fellows, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Bringing together theoretical writing on objects, testimony, and J. M. Coetzee; testimony; trauma to develop the category of the “nonhuman witness,” this nonhuman; objects; essay considers the narrative, ethical, and ecological work performed ecocriticism; postcolonialism by peripheral objects in J. M. Coetzee’s Dusklands (1974). Coetzee’s insistent object catalogues acquire narrative agency and provide material for a counter-narrative parody of first-personal reports of violence in Dusklands. Such collections of nonhuman witnesses further disclose the longer temporality of ecological violence that extends beyond the text’s represented and imagined casualties. Linking the paired novellas of Dusklands, which concern 1970s America and 1760s South Africa, the essay finds in Coetzee’s strange early work a durable ethical contribution to South African literature precisely for its attention to nonhuman claimants and environments. -

The Failure of Sympathy in the Recent Works of J.M. Coetzee

The failure of sympathy in the recent works of JM Coetzee Warwick Ian Shapcott A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts (Research) School of English University of New South Wales July 2006 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT 'I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.' Signed ......... Date ........................ ..~~.l.~.l~.7 ......................... COPYRIGHT STATEMENT 'I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). -

Aeronautics and Space Report of the President

Aeronautics and Space Report of the President 1971 Activities NOTE TO READERS: ALL PRINTED PAGES ARE INCLUDED, UNNUMBERED BLANK PAGES DURING SCANNING AND QUALITY CONTROL CHECK HAVE BEEN DELETED Aeronautics and Space Report of the President 197 I Activities i W Executive Office of the President National Aeronautics and Space Council Washington, D.C. 20502 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE OF TRANSMITTAL To the Congress of the United States: I am pleased to transmit herewith a report of our national progress in aero- nautics and space activities during 1971. This report shows that we have made forward strides toward each of the six objectives which I set forth for a balanced space program in my statement of March 7, 1970. Aided by the improvements we have made in mobility, our explorers on the moon last summer produced new, exciting and useful evidence on the structure and origin of the moon. Several phenomena which they uncovered are now under study. Our unmanned nearby observation of Mars is similarly valuable and significant for the advancement of science. During 1971, we gave added emphasis to aeronautics activities which contribute substantially to improved travel conditions, safety and security, and we gained in- creasing recognition that space and aeronautical research serves in many ways to keep us in the forefront of man’s technological achievements. There can be little doubt that the investments we are now making in explora- tions of the unknown are but a prelude to the accomplishments of mankind in future generations. THEWHITE HOUSE, March 1972 iii Table of Contents Page Page I . Progress Toward U.S. -

(Title of the Thesis)*

J.M. COETZEE AND THE LIMITS OF COSMOPOLITAN FEELING by Katherine Marta Kouhi Hallemeier A thesis submitted to the Department of English Language and Literature In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (June, 2012) Copyright ©Katherine Marta Kouhi Hallemeier, 2012 Abstract In this dissertation, I argue that accounts of cosmopolitan literature tend to equate cosmopolitanism with sympathetic feeling. I further contend that sympathy is in fact implicitly central to a wider body of contemporary cosmopolitan theory. I distinguish between two strains of cosmopolitan thought that depend upon two distinct models of feeling: “critical cosmopolitanism,” which depends upon a cognitive-evaluative model of sympathy, and “affective cosmopolitanism,” which depends upon a relational model. Both branches of cosmopolitanism envision sympathy as perfectly human or humane; they gloss over the potential for feeling shame in cosmopolitan encounters. The minority of scholarship that does consider shame in relation to cosmopolitan practice also reifies shame as ideally human or humane. Whether through sympathy or shame, cosmopolitan subjects become cosmopolitan through feeling. I offer readings of J.M. Coetzee’s later fiction in order to critique the idealization of feeling as distinctly cosmopolitan. Coetzee’s work, I conclude, suggests another model for cosmopolitanism, one which foregrounds the limits of feeling for realizing mutuality and equality. ii Acknowledgements I am profoundly grateful to those mentors and friends who supported me throughout the writing of this dissertation. My thanks go to Rosemary Jolly, whose vision of what literary studies can be will always inspire me. I am thankful, too, to Chris Bongie, for his generous, incisive, and meticulous reading of my work. -

Coming Into Being: J. M. Coetzee's "Slow Man" and the Aesthetic of Hospitality Author(S): Michael Marais Source: Contemporary Literature, Vol

Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System Coming into Being: J. M. Coetzee's "Slow Man" and the Aesthetic of Hospitality Author(s): Michael Marais Source: Contemporary Literature, Vol. 50, No. 2 (Summer, 2009), pp. 273-298 Published by: University of Wisconsin Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20616426 Accessed: 28-06-2016 06:05 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Wisconsin Press, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Contemporary Literature This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Tue, 28 Jun 2016 06:05:10 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms MICHAEL MARAIS Coming into Being: J. M. Coetzee's Slow Mon and the Aesthetic of Hospitality While much of his critical work on J. M. Coetzee's writing is informed by a sophisticated understand ing of Derridean hospitality, Derek Attridge has _seldom used this term himself?the exception being his insightful reading of The Master of Petersburg (J. M. Coetzee 122-24). In fact, very little criticism to date has examined Coetzee's use of the metaphor of hospitality in his writing. -

9538\Ariel View.Pdf

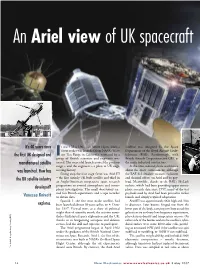

Cover story.qxd 2/5/07 4:59 pm Page 14 An Ariel view of UK spacecraft It’s 40 years since t was 5 May 1967, just before 12pm, when a satellite was designed by the Space Scout rocket was launched from NASA’s West- Department of the Royal Aircraft Estab- the first UK designed and I ern Test Range in California, witnessed by a lishment (RAE), Farnborough, with group of British scientists and engineers wit- British Aircraft Corporation and GEC as manufactured satellite nessed. The successful launch assured the precious the main industrial contractors. cargo – and the engineers – a place in UK engi- At the time, relatively little was known was launched. How has neering history. about the space environment, although Sitting atop the four stage Scout was Ariel III the RAE did simulate vacuum, radiation – the first entirely UK built satellite and third in and thermal effects on Ariel and its pay- the UK satellite industry an Anglo-American cooperative space research load. Meanwhile, thanks to the RAE’s SkyLark programme to extend atmospheric and ionos- rockets, which had been providing upper atmos- developed? pheric investigations. The small observatory car- phere research data since 1957, many of the test ried five British experiments and a tape recorder payloads used by Ariel had been proved in rocket Vanessa Knivett to obtain data. launch and simply required adaptation. Sputnik 1, the first man made satellite, had Ariel III was approximately 66in high and 30in explores. been launched almost 10 years earlier, on 4 Octo- in diameter. Four booms hinged out from the ber 1957. -

Jm Coetzee and Animal Rights

J.M. COETZEE AND ANIMAL RIGHTS: ELIZABETH COSTELLO’S CHALLENGE TO PHILOSOPHY Richard Alan Northover SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ENGLISH LITERATURE IN THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA PRETORIA, 0002, SOUTH AFRICA Supervisor: Professor David Medalie OCTOBER 2009 © University of Pretoria Abstract The thesis relates Coetzee’s focus on animals to his more familiar themes of the possibility of fiction as a vehicle for serious ethical issues, the interrogation of power and authority, a concern for the voiceless and the marginalised, a keen sense of justice and the question of secular salvation. The concepts developed in substantial analyses of The Lives of Animals and Disgrace are thereafter applied to several other works of Coetzee. The thesis attempts to position J.M. Coetzee within the animal rights debate and to assess his use of his problematic persona, Elizabeth Costello, who controversially uses reason to attack the rationalism of the Western philosophical tradition and who espouses the sympathetic imagination as a means of developing respect for animals. Costello’s challenge to the philosophers is problematised by being traced back to Plato’s original formulation of the opposition between philosophers and poets. It is argued that Costello represents a fallible Socratic figure who critiques not reason per se but an unqualified rationalism. This characterisation of Costello explains her preoccupation with raising the ethical awareness of her audience, as midwife to the birth of ideas, and perceptions of her as a wise fool, a characterisation that is confirmed by the use of Bakhtin’s notion of the Socratic dialogue as one of the precursors of the modern novel. -

Desind Finding

NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE ARCHIVES Herbert Stephen Desind Collection Accession No. 1997-0014 NASM 9A00657 National Air and Space Museum Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC Brian D. Nicklas © Smithsonian Institution, 2003 NASM Archives Desind Collection 1997-0014 Herbert Stephen Desind Collection 109 Cubic Feet, 305 Boxes Biographical Note Herbert Stephen Desind was a Washington, DC area native born on January 15, 1945, raised in Silver Spring, Maryland and educated at the University of Maryland. He obtained his BA degree in Communications at Maryland in 1967, and began working in the local public schools as a science teacher. At the time of his death, in October 1992, he was a high school teacher and a freelance writer/lecturer on spaceflight. Desind also was an avid model rocketeer, specializing in using the Estes Cineroc, a model rocket with an 8mm movie camera mounted in the nose. To many members of the National Association of Rocketry (NAR), he was known as “Mr. Cineroc.” His extensive requests worldwide for information and photographs of rocketry programs even led to a visit from FBI agents who asked him about the nature of his activities. Mr. Desind used the collection to support his writings in NAR publications, and his building scale model rockets for NAR competitions. Desind also used the material in the classroom, and in promoting model rocket clubs to foster an interest in spaceflight among his students. Desind entered the NASA Teacher in Space program in 1985, but it is not clear how far along his submission rose in the selection process. He was not a semi-finalist, although he had a strong application. -

Agency, Narrative, and Silence in JM Coetzee's Foe and Slow

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2019-09-13 What is Done in Silence: Agency, Narrative, and Silence in J.M. Coetzee’s Foe and Slow Man Bauhart, Stephen Bauhart, S. (2019). What is Done in Silence: Agency, Narrative, and Silence in J.M. Coetzee’s Foe and Slow Man (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/111070 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY What is Done in Silence: Agency, Narrative, and Silence in J.M. Coetzee’s Foe and Slow Man by Stephen Bauhart A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2019 © Stephen Bauhart 2019 Abstract My thesis analyzes J.M. Coetzee’s novels Slow Man and Foe to show how Coetzee presents silence and agency in relation to each other. The two novels will be looked at separately, first with Slow Man revealing that Coetzee is rejecting a Platonic metaphysic of the self and adopting something like a Nietzschean construction of language in order to show how in the case of Paul Rayment, the protagonist, silence is productive and allows for him to become an agent in the world.