The Beginning of Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

NCTE and IRA Joint Committee on the Impact of Child Association, 800 Barksdale Rd., Box 8139, Newark, DE Language; Classroom

DOCUMENT RESUME EIS 251 857 CS 208 718 AUTHOR Jaggar, Angela, Ed.; Smith-Burke, M. Trika, Ed. TITLE Observing the Language Levrner. INSTITUTION International Reading Association, Newark, Del.; National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-87207-890-6 PUB DATE 85 NOTE 261p.; This publication is the result of work of the NCTE and IRA Joint Committee on the Impact of Child Language Development Research on Curriculum and Instruction and of the "Impact Conference" sponsored by that committee. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 33991, $11.00 nonmember, $8.00 member); International Reading Association, 800 Barksdale Rd., Box 8139, Newark, DE 19714 (Book. Order No. 890, $11.00 nonmember, $8.00 msmber). PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) -- Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Beginning Reading; *Child Development; Child Language; Classroom Environment; *Classroom Observation Techniques; *Classroom Techniques; Elementary Education; *Language Acquisition; Language Patterns; *Language Processing; Language Research; *Learning Strategies; Literature Appreciation; Oral Language; Student Behavior; Teacher Student Relationship; Writing Instruction ABSTRACT Intended for teachers and others having responsibility for shaping language policy in the schools, this collection of invited, original articles is based on tha belief that a teacher's task is not to "teach" children language but,rather, to create an environment that will allow language learning to occur naturally. The book is divided into four interrelated parts. The two chapters in the first part provide the rationale for observing children's language and establish the central theme. Parts two and three comprise the heart of the book and deal with the different, but overlapping, facets of language development described by M. -

American Notes for General Circulation

AMERICAN NOTES FOR GENERAL CIRCULATION PREFACE TO THE FIRST CHEAP EDITION OF "AMERICAN NOTES" IT is nearly eight years since this book was first published. I present it, unaltered, in the Cheap Edition; and such of my opinions as it expresses, are quite unaltered too. My readers have opportunities of judging for themselves whether the influences and tendencies which I distrust in America, have any existence not in my imagination. They can examine for themselves whether there has been anything in the public career of that country during these past eight years, or whether there is anything in its present position, at home or abroad, which suggests that those influences and tendencies really do exist. As they find the fact, they will judge me. If they discern any evidences of wrong- going in any direction that I have indicated, they will acknowledge that I had reason in what I wrote. If they discern no such thing, they will consider me altogether mistaken. Prejudiced, I never have been otherwise than in favour of the United States. No visitor can ever have set foot on those shores, with a stronger faith in the Republic than I had, when I landed in America. I purposely abstain from extending these observations to any length. I have nothing to defend, or to explain away. The truth is the truth; and neither childish absurdities, nor unscrupulous contradictions, can make it otherwise. The earth would still move round the sun, though the whole Catholic Church said No. I have many friends in America, and feel a grateful interest in the country. -

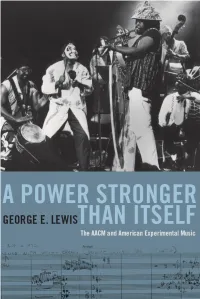

A Power Stronger Than Itself

A POWER STRONGER THAN ITSELF A POWER STRONGER GEORGE E. LEWIS THAN ITSELF The AACM and American Experimental Music The University of Chicago Press : : Chicago and London GEORGE E. LEWIS is the Edwin H. Case Professor of American Music at Columbia University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2008 by George E. Lewis All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the United States of America 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewis, George, 1952– A power stronger than itself : the AACM and American experimental music / George E. Lewis. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ), discography (p. ), and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians—History. 2. African American jazz musicians—Illinois—Chicago. 3. Avant-garde (Music) —United States— History—20th century. 4. Jazz—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3508.8.C5L48 2007 781.6506Ј077311—dc22 2007044600 o The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. contents Preface: The AACM and American Experimentalism ix Acknowledgments xv Introduction: An AACM Book: Origins, Antecedents, Objectives, Methods xxiii Chapter Summaries xxxv 1 FOUNDATIONS AND PREHISTORY -

Reference Guide This List Is for Your Reference Only

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

LYRIQ BENT Winner on Canada’S Talent

Fall 2016 Inaugural TIFF issue! LYRIQ BENTThe Canadian Screen Award winner on why this country is becoming a global production power player What do Canadians want (to watch)? We have the answers inside And the nominees are… Check out who’s up for the 2016 CMPA Feature Film Producer Awards at TIFF Q&As with Canada’s talent 31 Q&A: Kim Todd Service stereotypes and IP ownership 40 Q&A: David Way Why authenticity matters 50 Q&A: Jay Bennett Brave new worlds 64 Q&A: Mike Volpe Laughing all the way 74 Q&A: Jillianne Reinseth Engaging children (and parents) 8 Cover feature The Canadian Screen Award Page 11 Page 42 LYRIQ BENT winner on Canada’s talent Features Page 55 Page 83 2 Reynolds Mastin 48 Taken A letter from the President Tackling a tough topic and CEO of the CMPA with empathy 11 Canadian Film Pictured (top to bottom): Black Code, Giants of Africa, Nelly Pictured (top to bottom): X Quinientos, Maudie, Maliglutit (Searchers) Pictured (top to bottom): Mean Dreams, Anatomy of Violence, Pays 4 The Big Picture 61 Feeling the Love! 32 Foreign Location · A look at TV, film and media A data-driven case for Service Production Film across Canada made-in-Canada content 41 Canadian THE 6 And the Nominees Are… 62 Behind the Scenes Documentary Film Leads negotiations with unions, broadcasters and funders The CMPA Feature Film A photographic look at filming Producer Awards and production across Canada Explores new digital and international business models 51 Canadian TV ∙ Builds opportunities for established and emerging content creators 72 Changing the Channel Drama CMPA Women in production 65 Canadian TV ∙ 86 The Indiescreen Listicle Comedy Through international delegations, best-in-class professional development, mentorship programs and more, Which Canadian film are you? the CMPA advances the interests of Canada’s indie producers. -

Entire Issue (PDF 2MB)

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 164 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 7, 2018 No. 24 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was come forward and lead the House in the this Friday. I cannot think of an offi- called to order by the Speaker. Pledge of Allegiance. cer more deserving than Officer Sean f Mrs. MURPHY of Florida led the Gallagher, and I congratulate him for Pledge of Allegiance as follows: his heroism. PRAYER I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the The Chaplain, the Reverend Patrick United States of America, and to the Repub- f J. Conroy, offered the following prayer: lic for which it stands, one nation under God, Thank You, God, for giving us an- indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. CELEBRATING THE 325TH ANNI- other day. Please bless the Members of f VERSARY OF THE COLLEGE OF the people’s House and the men and ANNOUNCEMENT BY THE SPEAKER women of the Senate in these waning WILLIAM & MARY The SPEAKER. The Chair will enter- days of funding for the government. (Mrs. MURPHY of Florida asked and tain up to five requests for 1-minute May their efforts to find a workable was given permission to address the speeches on each side of the aisle. solution to difficult issues result in House for 1 minute and to revise and legislation that will redound to the f extend her remarks.) benefit of our Nation. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 141 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 1995 No. 148 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was vide for joint natural resource management model called the flush model is being called to order by the Speaker pro tem- and enforcement of laws and regulations per- used by Federal agencies as the basis pore [Mr. HAYWORTH]. taining to natural resources and boating at for Columbia River salmon recovery ef- the Jennings Randolph Lake Project lying in forts. While this model is used to jus- f Garrett County, Maryland and Mineral tify reservoir drawdowns and spend DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO County, West Virginia, entered into between the States of West Virginia and Maryland; hundreds of millions of dollars of ex- TEMPORE and penditures, its scientific base has never The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- S. Con. Res. 27. Concurrent resolution cor- been made public nor subject to peer fore the House the following commu- recting the enrollment of H.R. 402. review. nication from the Speaker: f Despite months of repeated requests, I have not been able to obtain this WASHINGTON, DC, September 21, 1995. THE JOURNAL model. The Resources Committee, I hereby designate the Honorable J.D. The SPEAKER pro tempore (Mr. under Chairman YOUNG, will issue a HAYWORTH to act as Speaker pro tempore on HAYWORTH). The Chair has examined formal request for a copy of this model, this day. the Journal of the last day's proceed- but this information should have been NEWT GINGRICH, ings and announces to the House his available for public and peer review be- Speaker of the House of Representatives.