Newsletter 22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semester Iv British Poetry-Iv (Mael 606)

PROGRAMME CODE: MAEL 20 SEMESTER III BRITISH POETRY- III (MAEL 601) SEMESTER IV BRITISH POETRY-IV (MAEL 606) “ “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,”-that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know” John Keats SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES Uttarakhand Open University PROGRAMME CODE: MAEL 20 SEMESTER III BRITISH POETRY- III (MAEL 601) SEMESTER IV BRITISH POETRY-IV (MAEL 606) SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES Uttarakhand Open University Phone nos. 05964-261122, 261123 Toll Free No. 18001804025 Fax No. 05946-264232, e-mail info @uou.ac.in http://uou.ac.in Board of Studies Prof. H.P.Shukla (Chairperson) Prof. S.A.Hamid (Retd.) Director Dept. of English School of Humanities Kumaun University Uttarakhand Open University Nainital Haldwani Prof. D.R.Purohit Prof. M.R.Verma Senior Fellow Dept. of English Indian institute of Advanced studies Gurukul Kangri University Shimla, Himachal Pradesh Haridwar Programme Developers and Editors Dr. H.P. Shukla Dr. Suchitra Awasthi(Coordinator) Professor,Dept. of English Assistant Professor Director,School of humanities Dept. of English Uttarakhand Open University Uttarakhand Open University Unit Writers Dr. R.B. Sharma Semester III- Unit 1, 2 Lucknow University, Lucknow Dr. M.M. Tripathi Semester III - Units 3, 4, 5, 6 DAV College, Kanpur Dr. Manjula Namboori Semester IV- Units 1, 2, 3 Govt. Raza PG College, Rampur Dr. Veerendra Mishra Semester IV- Units 4, 5 IIT, Roorkee Dr. Andhruti Shah Semester IV -Units 6,7,8 Shivalik College of Engineering, Dehradun Edition: 2020 ISBN : 978-93-84632-16-8 Copyright: Uttarakhand Open University, Haldwani Published by: Registrar, Uttarakhand Open University, Haldwani Email: [email protected] Printer: CONTENTS SEMESTER III MAEL 601 BLOCK 1 : EARLY ROMANTIC POETRY Unit 1 William Wordsworth “Tintern Abbey” 02-11 Unit 2 Samuel Taylor Coleridge “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” 12-28 BLOCK 2: LATER ROMANTIC POETRY Unit 3 P.B. -

V. L. 0. Chittick ANGRY YOUNG POET of the THIRTIES

V. L. 0. Chittick ANGRY YOUNG POET OF THE THIRTIES THE coMPLETION OF JoHN LEHMANN's autobiography with I Am My Brother (1960), begun with The Whispering Gallery (1955), brings back to mind, among a score of other largely forgotten matters, the fact that there were angry young poets in England long before those of last year-or was it year before last? The most outspoken of the much earlier dissident young verse writers were probably the three who made up the so-called "Oxford group", W. ·H. Auden, Stephen Spender, and C. Day Lewis. (Properly speaking they were never a group in col lege, though they knew one ariother as undergraduates and were interested in one another's work.) Whether taken together or singly, .they differed markedly from the young poets who have recently been given the label "angry". What these latter day "angries" are angry about is difficult to determine, unless indeed it is merely for the sake of being angry. Moreover, they seem to have nothing con structive to suggest in cure of whatever it is that disturbs them. In sharp contrast, those whom they have displaced (briefly) were angry about various conditions and situations that they were ready and eager to name specifically. And, as we shall see in a moment, they were prepared to do something about them. What the angry young poets of Lehmann's generation were angry about was the heritage of the first World War: the economic crisis, industrial collapse, chronic unemployment, and the increasing tP,reat of a second World War. -

Evolvong Wilds: Auden, Ecology, and the Formation of a New Poetics

EVOLVONG WILDS: AUDEN, ECOLOGY, AND THE FORMATION OF A NEW POETICS A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Jeremy Davis Jagger May 2020 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials i Thesis written by Jeremy Davis Jagger B.A., Malone University 2016 M.A., Kent State University, 2020 Approved by Dr. Tammy Clewell, PhD. , Advisor Dr. Robert Trogdon, PhD. , Chair, Department of English Dr. James Blank, PhD. , Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS………………………………………………………………………...iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………………..iv CHAPTERS I. A Legacy in Crisis…………………………………………………………………….1 II. A Brief Note on Sacred Objects………………………………………………………6 III. Ecology in the Audenesque………………………………………………………….11 IV. Auden, Politics, and Hints of the Ecological………………………………………...26 V. America, Yeats, and a New Poetics………………………………………………….45 VI. A Reformed Poetics in Practice……………………………………………………...53 VII. When Nature and Culture Collide……………………………………………………72 VIII. A Legacy Cemented………………………………………………………………….86 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………………..89 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to thank Dr. Tammy Clewell for her many contributions to the production of this text. He would also like to acknowledge the contributions of his committee, Dr. Ryan Hediger and Dr. Babacar M’Baye. iv A Legacy in Crisis For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives In the valley of its making where executives Would never want to tamper, flows on south From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs, Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives, A way of happening, a mouth. —W.H. Auden, “In Memory of W.B. Yeat “The unacknowledged legislators of the world” describes the secret police, not the poets. -

Sharpe, Tony, 1952– Editor of Compilation

more information - www.cambridge.org/9780521196574 W. H. AUDen IN COnteXT W. H. Auden is a giant of twentieth-century English poetry whose writings demonstrate a sustained engagement with the times in which he lived. But how did the century’s shifting cultural terrain affect him and his work? Written by distinguished poets and schol- ars, these brief but authoritative essays offer a varied set of coor- dinates by which to chart Auden’s continuously evolving career, examining key aspects of his environmental, cultural, political, and creative contexts. Reaching beyond mere biography, these essays present Auden as the product of ongoing negotiations between him- self, his time, and posterity, exploring the enduring power of his poetry to unsettle and provoke. The collection will prove valuable for scholars, researchers, and students of English literature, cultural studies, and creative writing. Tony Sharpe is Senior Lecturer in English and Creative Writing at Lancaster University. He is the author of critically acclaimed books on W. H. Auden, T. S. Eliot, Vladimir Nabokov, and Wallace Stevens. His essays on modernist writing and poetry have appeared in journals such as Critical Survey and Literature and Theology, as well as in various edited collections. W. H. AUDen IN COnteXT edited by TONY SharPE Lancaster University cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Mexico City Cambridge University Press 32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10013-2473, USA www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521196574 © Cambridge University Press 2013 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

Copyright by Jonathon N. Anderson 2019

Copyright by Jonathon N. Anderson 2019 GENRE AND AUDIENCE RECEPTION IN THE RAKE’S PROGRESS by Jonathon N. Anderson, BM THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The University of Houston-Clear Lake In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements For the Degree MASTER OF ARTS in Literature THE UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON-CLEAR LAKE MAY, 2019 GENRE AND AUDIENCE RECEPTION IN THE RAKE’S PROGRESS by Jonathon N. Anderson APPROVED BY __________________________________________ David D. Day, J.D., Ph.D., Chair __________________________________________ Craig H. White, Ph.D., Committee Member RECEIVED/APPROVED BY THE COLLEGE OF HUMAN SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES: Samuel Gladden, Ph.D., Associate Dean __________________________________________ Rick J. Short, Ph.D., Dean Acknowledgements To Drs. White and Day, I offer my gratitude for your willingness to let me follow tangents and guesses throughout my graduate career. Dr. White, your generous indulgence, encouragement, and patient guidance helped me refine my fuzzy hunches to clearly articulated ideas. Dr. Day, your depth of knowledge on, enthusiasm for, and sense of humor with medieval works brings them to life and illuminates their continued relevance. I appreciate the priority both of you place on the excitement conjured by texts ancient and modern. To my parents, I offer my gratitude for maintaining a house strewn with interesting books waiting to be discovered. Mom, I appreciate all our late-night conversations about whatever random volume I happened to be curious about at the time. Dad, I hope I’m making good on the lifetime of blind confidence in my abilities you’ve given me. To Peg and Ed, the best in-laws anybody could ask for, thank you for your inspiration and advice. -

“The Auden Group”

1 Subject: ENGLISH Class: B.A. Part 1 English Hons., Paper-1, Group B Topic: THE AUDEN GROUP Lecture No: 20 By: Prof. Sunita Sinha Head, Department of English Women’s College Samastipur L.N.M.U., Darbhanga Email: [email protected] Website: www.sunitasinha.com Mob No: 9934917117 “THE AUDEN GROUP” INTRODUCTION • The Auden Group or the Auden Generation is a group of British and Irish writers active in the 1930s that included W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender, Cecil Day Lewis, Louis MacNeice and Christopher Isherwood. • The Auden Group is also sometimes referred to as the Nineteen Thirties Poets or The Oxford Poets who represented a new, more experimental literary style. • All the poets knew one another, and most had been educated at either Oxford or Cambridge, all sharing vaguely left-wing viewpoints. The writers associated with the grouping—W. H. Auden, Louis MacNeice, Cecil Day- 2 Lewis, Stephen Spender, Christopher Isherwood never gathered together in the same room, nor shared any coherent poetic or literary values. • Rather, the poets connected individually, particularly through Auden, who collaborated several times with both Isherwood and MacNeice, and wrote with Day-Lewis an introduction to the annual Oxford Poetry. • In the public mind, the individuals continued to be linked, with poet Roy Campbell referring to “MacSpaunday” in his 1946 work, Talking Bronco, a word created from the names of MacNeice (Mac), Spender (sp), Auden (au- n), and Day-Lewis (day). • The English Poetry of 1930s is primarily recognized as the poetry of leftist philosophy. The poets during this period were highly influenced by the philosophy of Karl Marx and his followers. -

ABSTRACT Augustinian Auden: the Influence of Augustine of Hippo on W. H. Auden Stephen J. Schuler, Ph.D. Mentor: Richard Rankin

ABSTRACT Augustinian Auden: The Influence of Augustine of Hippo on W. H. Auden Stephen J. Schuler, Ph.D. Mentor: Richard Rankin Russell, Ph.D. It is widely acknowledged that W. H. Auden became a Christian in about 1940, but relatively little critical attention has been paid to Auden‟s theology, much less to the particular theological sources of Auden‟s faith. Auden read widely in theology, and one of his earliest and most important theological influences on his poetry and prose is Saint Augustine of Hippo. This dissertation explains the Augustinian origin of several crucial but often misunderstood features of Auden‟s work. They are, briefly, the nature of evil as privation of good; the affirmation of all existence, and especially the physical world and the human body, as intrinsically good; the difficult aspiration to the fusion of eros and agape in the concept of Christian charity; and the status of poetry as subject to both aesthetic and moral criteria. Auden had already been attracted to similar ideas in Lawrence, Blake, Freud, and Marx, but those thinkers‟ common insistence on the importance of physical existence took on new significance with Auden‟s acceptance of the Incarnation as an historical reality. For both Auden and Augustine, the Incarnation was proof that the physical world is redeemable. Auden recognized that if neither the physical world nor the human body are intrinsically evil, then the physical desires of the body, such as eros, the self-interested survival instinct, cannot in themselves be intrinsically evil. The conflict between eros and agape, or altruistic love, is not a Manichean struggle of darkness against light, but a struggle for appropriate placement in a hierarchy of values, and Auden derived several ideas about Christian charity from Augustine. -

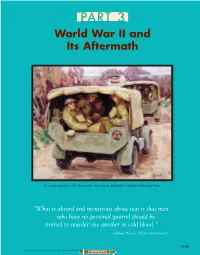

PART 3 World War II and Its Aftermath

PART 3 World War II and Its Aftermath It’s a Long, Long Way, 1941. Henry Lamb. Oil on canvas. South African National Gallery, Cape Town. “What is absurd and monstrous about war is that men who have no personal quarrel should be trained to murder one another in cold blood.” —Aldous Huxley, “Words and Behavior” 1165 Henry Lamb/ South African National Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa/Bridgeman Art Library 11165165 U6P3-845482.inddU6P3-845482.indd Sec2:1165Sec2:1165 11/29/07/29/07 1:57:121:57:12 PMPM BEFORE YOU READ Be Ye Men of Valor MEET WINSTON CHURCHILL “ lood, toil, tears, and sweat.” These unforget- Political Career Churchill’s military experience table words of Winston Churchill were not and his background as a writer gave him a unique Bmerely a rallying cry, but his approach to advantage in the political realm. He served in life. He is perhaps one of the most renowned prime numerous positions in Parliament, including home ministers of Great Britain, inspiring a nation and secretary, first lord of the Admiralty, minister of leading it to victory in the face of World War II. munitions, secretary of state for war and air, and secretary for the colonies. In 1940 Churchill became prime minister just as the Germans invaded Belgium—a post he held until the end of the war and “You ask, what is our aim? I can the defeat of the Axis powers. answer in one word: Victory—victory A Literary Knight At the age of seventy-one, at all costs, victory in spite of all Churchill was voted out of office as prime min ister, terror; victory, however long and hard but he was reelected six years later. -

MA Thesis Eveline De Smalen

“Dreaming of Elsewhere”: Landscape in W.H. Auden M.A. Thesis Comparative Literary Studies, Utrecht University Eveline de Smalen 3701638 Supervisor: Prof. Dr David Pascoe Second reader: Dr Kári Driscoll 21 August 2015 38,038 words 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 “Truth Is Elsewhere”: Crossing Borders in England, Germany and the Nordic Countries 18 “Oh How I Wish That Situation Mine”: English Mining Landscapes 20 “Nicht Mehr in Berlin ”: Auden in Germany 31 “The Magical Light Beyond Hekla”: The Nordic Countries 47 “What Could Be More Like Mother”: Freudian Landscapes 59 “An Important Jew Who Died in Exile”: The Borders of Freud 61 “Never, Thank God, in Step”: The Necessity of Borders 70 “Dislodged from Elsewhere”: Auden in Exile 80 “My Cosmos is Contracted”: Landscapes of Religion 93 “Gone the Boundary Stone”: Auden and Co-Inherence 96 “You Have to Leap before You Look”: Borders and the Leap of Faith 107 “A Place I May Go Both in And out of”: Coming Home 121 Conclusion 131 Appendix: Landscape Photographs 135 Works Cited 143 3 Introduction In 1950, Wystan Hugh Auden wrote “In Transit,” on the occasion of his plane making a stopover at Shannon Airport in “Mad Ireland” (“W.B. Yeats” 34) on the way to continental Europe 1. This poem, in which words like “somewhere,” “elsewhere,” and “nowhere” abound, shows the airport as a non-place representative of modernity. Marc Augé has theorised the concept of the non-place, writing that If a place can be defined as relational, historical and concerned with identity, then a place which cannot be defined as relational, or historical, or concerned with identity will be a non-place. -

1. Taming the Monster 1. Geoffrey Grigson, 'Auden As a Monster', New

Notes 1. Taming the Monster 1. Geoffrey Grigson, ‘Auden as a Monster’, New Verse, 26–7 (1937), 13–17 (p. 13). 2. New Signatures appeared for the first time in 1932, New Country in 1933; New Verse was published from January 1933 until January 1939, New Writing from Spring 1936 until 1950. See Samuel Hynes, The Auden Generation: Literature and Politics in England in the 1930s (London and Boston: Faber & Faber, 1976), pp. 74–5, 102, 114, 198. 3. Richard Hoggart’s Auden: An Introductory Essay (London: Chatto & Windus, 1951), the first and surprisingly good study of Auden’s works, set the tone with the remark ‘Auden’s poetry is particularly concerned with the pressures of the times’, p. 9. 4. François Duchêne, The Case of the Helmeted Airman: A Study of W. H. Auden’s Poetry (London: Chatto & Windus, 1972) is an unpleasant example of this vivisection attitude that regards the author as a part of the texts and endeavours to supply its reader not only with a textual analysis, but glimpses of the author’s psyche. Herbert Greenberg, Quest for the Necessary: W. H. Auden and the Dilemma of Divided Con- sciousness (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1968) is a more sensitive study. 5. Auden himself proves a perceptive commentator on such attitudes when he writes in the preface to The Poet’s Tongue of 1935, ‘The psy- chologist maintains that poetry is a neurotic symptom, an attempt to compensate by phantasy for a failure to meet reality. We must tell him that phantasy is only the beginning of writing; that, on the contrary, like psychology, poetry is a struggle to reconcile the unwilling subject and object; in fact, that since psychological truth depends so largely on context, poetry, the parabolic approach, is the only adequate medium for psychology’ (Pr 108). -

Auden at Work / Edited by Bonnie Costello, Rachel Galvin

Copyrighted material – 978–1–137–45292–4 Introduction, selection and editorial matter © Bonnie Costello and Rachel Galvin 2015 Individual chapters © Contributors 2015 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2015 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978–1–137–45292–4 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. -

Auden's Revisions

Auden’s Revisions By W. D. Quesenbery for Marilyn and in memoriam William York Tindall Grellet Collins Simpson © 2008, William D. Quesenbery Acknowledgments Were I to list everyone (and their affiliations) to whom I owe a debt of gratitude for their help in preparing this study, the list would be so long that no one would bother reading it. Literally, scores of reference librarians in the eastern United States and several dozen more in the United Kingdom stopped what they were doing, searched out a crumbling periodical from the stacks, made a Xerox copy and sent it along to me. I cannot thank them enough. Instead of that interminable list, I restrict myself to a handful of friends and colleagues who were instrumental in the publication of this book. First and foremost, Edward Mendelson, without whose encouragement this work would be moldering in Columbia University’s stacks; Gerald M. Pinciss, friend, colleague and cheer-leader of fifty-odd years standing, who gave up some of his own research time in England to seek out obscure citations; Robert Mohr, then a physics student at Swarthmore College, tracked down citations from 1966 forward when no English literature student stepped forward; Ken Prager and Whitney Quesenbery, computer experts who helped me with technical problems and many times saved this file from disappearing into cyberspace;. Emily Prager, who compiled the Index of First Lines and Titles. Table of Contents Acknowledgments 3 Table of Contents 4 General Introduction 7 Using the Appendices 14 PART I. PAID ON BOTH SIDES (1928) 17 Appendix 19 PART II.