Chapter- V Representation of Social Change in Kayar: a Historical Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vaikom Muhammad Basheer and Indian Literature Author(S): K

Sahitya Akademi Vaikom Muhammad Basheer and Indian Literature Author(s): K. Satchidanandan Source: Indian Literature, Vol. 53, No. 1 (249) (January/February 2009), pp. 57-78 Published by: Sahitya Akademi Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23348483 Accessed: 25-03-2020 10:34 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Sahitya Akademi is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Indian Literature This content downloaded from 103.50.151.143 on Wed, 25 Mar 2020 10:34:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A BIRTH CENTENARY TRIBUTE Vaikom Muhammad Basheer and Indian Literature K. Satchidanandan I Vaikom like Muhammadto call the democratic Basheer tradition (1908-1994) in Indian belongsliterature, firmly a living tradition to what I that can be traced back to the Indian tribal lore including the Vedas and the folktales and fables collected in Somdeva's Panchatantra and Kathasaritsagar, Gunadhya's Brihatkatha, Kshemendra's Brihatkathamanjari, the Vasudeva Hindi and the Jatakas. This tradition was further enriched by the epics, especially Ramayana and Mahabharata that combined several legends from the oral tradition and are found in hundreds of oral, performed and written versions across the nation that interpret the tales from different perspectives of class, race and gender and with different implications testifying to the richness and diversity of Indian popular imagination and continue to produce new textual versions, including dalit, feminist and other radical interpretations and adaptations even today. -

List of Books 2018 for the Publishers.Xlsx

LIST I LIST OF STATE BARE ACTS TOTAL STATE BARE ACTS 2018 PRICE (in EDITION SL.No. Rupees) COPIES AUTHOR/ REQUIRED PRICE FOR EDN / YEAR PUBLISHER EACH COPY APPROXIMATE K.G. 1 Abkari Laws in Kerala Rajamohan/Ar latest 898 5 4490 avind Menon Govt. 2 Account Code I Kerala latest 160 10 1600 Publication Govt. 3 Account Code II Kerala latest 160 10 1600 Publication Suvarna 4 Advocates Act latest 790 1 790 Publication Advocate's Welfare Fund Act George 5 & Rules a/w Advocate's Fees latest 120 3 360 Johnson Rules-Kerala Arbitration and Conciliation 6 Rules (if amendment of 2016 LBC latest 80 5 400 incorporated) Bhoo Niyamangal Adv. P. 7 latest 1500 1 1500 (malayalam)-Kerala Sanjayan 2nd 8 Biodiversity Laws & Practice LBC 795 1 795 2016 9 Chit Funds-Law relating to LBC 2017 295 3 885 Chitty/Kuri in Kerala-Laws 10 N Y Venkit 2012 160 1 160 on Christian laws in Kerala Santhosh 11 2007 520 1 520 Manual of Kumar S Civil & Criminal Laws in 12 LBC 2011 250 1 250 Practice-A Bunch of Civil Courts, Gram Swamy Law 13 Nyayalayas & Evening 2017 90 2 180 House Courts -Law relating to Civil Courts, Grama George 14 Nyayalaya & Evening latest 130 3 390 Johnson Courts-Law relating to 1 LIST I LIST OF STATE BARE ACTS TOTAL STATE BARE ACTS 2018 PRICE (in EDITION SL.No. Rupees) COPIES AUTHOR/ REQUIRED PRICE FOR EDN / YEAR PUBLISHER EACH COPY APPROXIMATE Civil Drafting and Pleadings 15 With Model / Sample Forms LBC 2016 660 1 660 (6th Edn. -

Library Stock.Pdf

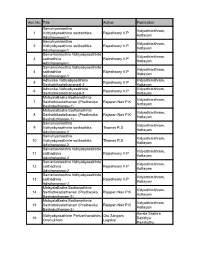

Acc.No. Title Author Publication Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 1 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 2 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 3 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 4 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 5 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 6 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 7 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 8 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 9 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 10 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 11 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 12 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 13 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 14 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-2) MalayalaBasha -

Acc.No. Title

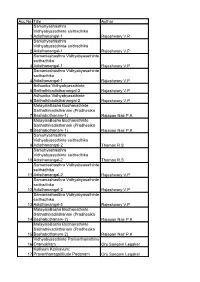

Acc.No. Title Author Samuhyashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 1 Adisthanangal-1 Rajeshwary V.P Samuhyashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 2 Adisthanangal-1 Rajeshwary V.P Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 3 Adisthanangal-1 Rajeshwary V.P Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 4 Adisthanangal-1 Rajeshwary V.P Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte 5 Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Rajeshwary V.P Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte 6 Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Rajeshwary V.P MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika 7 Bashabothanam-1) Rajapan Nair P.K MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika 8 Bashabothanam-1) Rajapan Nair P.K Samuhyashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 9 Adisthanangal-2 Thomas R.S Samuhyashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 10 Adisthanangal-2 Thomas R.S Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 11 Adisthanangal-2 Rajeshwary V.P Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 12 Adisthanangal-2 Rajeshwary V.P Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 13 Adisthanangal-2 Rajeshwary V.P MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika 14 Bashabothanam-2) Rajapan Nair P.K MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika 15 Bashabothanam-2) Rajapan Nair P.K Vidhyabyasathinte Parivarthanathinu 16 Oramukham Oru Sangam Legakar Kalliyum Kariyavum: 17 Pravarthanagallillude Padanam Oru Sangam Legakar MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika 18 Bashabothanam-2) Rajapan Nair P.K Adhunika Vidhyabyasaprakriya: 19 Vikasanavum Pravannathakallum Sivarajan -

Books & Authors

BOOKS & AUTHORS I. Alphabetical Listing of Books: A A Backward Place : Ruth Prawer Jhabwala A Bend in the Ganges : Manohar Malgonkar A Bend in the River : V. S. Naipaul A Billion is Enough : Ashok Gupta A Bride for the Sahib and Other Stories : Khushwant Singh A Brief History of Time : Stephen Hawking A Brush with Life : Satish Gujral A Bunch of Old Letters : Jawaharlal Nehru A Cabinet Secretary Looks Back : B. G. Deshmukh . A Call To Honour-In Service of Emergent India : Jaswant Singh A Captain's Diary : Alec Stewart A China Passage : John Kenneth Galbraith A Conceptual Encyclopaedia of Guru Gtanth Sahib : S. S. Kohli A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy : Karl Marx A Critique of Pure Reason : Immanuel Kant A Dangerous Place : Daniel Patrick Moynihan A Doctor's Story of Life and Death : Dr. Kakkana Subbarao & Arun K. Tiwari A Doll's House : Henrik Ibsen A Dream in Hawaii : Bhabani Bhattacharya A Farewell to Arms : Ernest Hemingway A Fine Balance : Rohinton Mistry A Foreign Policy for India : I. K. Gujral A Gift of Wings : Shanthi Gopalan A Handful of Dust : Evelyn Waugh A Himalayan Love Story : Namita Gokhale A House Divided : Pearl S. .Buck A Judge's Miscellany : M. Hidayatullah A Last Leap South : Vladimir Zhirinovsky A Long Way : P. V. Narasimha Rao A Man for All Seasons : Robert Bolt A Midsummer Night's Dream : William Shakespeare A Million Mutinies Now : V. S. Naipaul A New World : Amit Chaudhuri A Pair of Blue Eyes : Thomas Hardy A Passage to England : Nirad C. Chaudhuri A Passage to India : E. -

Contemporary Kerala

CONTEMPORARY KERALA MODULE-IV S.K.POTTAKKAD,THAKAZHI VALSA.M.A ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY LITTLE FLOWER COLLEGE, GURUVAYOOR 2018-2019 (VI-SEM B.A. HISTORY) S.K.POTTAKKAD Sankarankutty Pottekkad- S.K.Pottekkad-1913-1982 Famous Malayalam writer Won Jnanapith Award for his novel- Oru Desathinte Katha in 1980 Author of nearly 60 books- 10 novels, 24 short stories, 3 anthologies, 18 travelogues, 4 plays, a collection of essays, some articles. Kerala Sahithya Academy Award- 1961- Oru Theruvinte Katha Madras Govt Prize-1949- Vishakanyaka Kerala Sahithya Academy Award- 1972-Oru Desathinte Katha Kendra Sahithya Academy Award in 1977 for the same Calicut University- Doctor of Letters – March 1982 Born in Kozhikkode Quit his job as School Teacher to attend annual session of Indian national Congress at Tripunithara in 1939 Went to Bombay Returned to Kozhikkode in 1945 Went to Kashmir-travelled to Europe & Africa Returned and published 2 works- Kappirikalude Nattil, Innathe Europe- Travel experience, Culture, History Went to Ceylon, Malaysia & Indonesia in 1952 Visited Finland, Chechoslovakia & Russia in 1957 Very active in politics in 1960s Elected to Lok Sabha & worked as MP from 1962-67- selected from Thalassery Parliamentary constituency * S.K.Pottekkad is a writer of strong social commitment and ideals, possessing individualistic vision. Experiences as a traveller have greatly influenced his works He was a realistic- more importance was given to romantic Imagination Wrote on personal experience- communicated to the heart of the -

List of Books in Collection

Book Author Category Biju's remarks Vishishtaaharam Abdullah, Ummi Cookery dishes Nerchakkozhi Abraham, John Stories maverick film maker Daivavela Abraham, Vinu Stories journalist and writer Nashtanayika Abraham, Vinu Novel based on the life of Rosie, Malayalam cinema's first heroine Srinivasan Oru Pusthakam Abraham, Vinu (ed) Film tributes to Malayalam film personality Srinivasan Irakal Vettayadappedumpol Achuthanandan V.S Essay former Chief Minister of Kerala Nerinoppam Achuthanandan V.S Essay former Chief Minister of Kerala Samaram Thanne Jeevitham Achuthanandan V.S Autobiographyformer Chief Minister of Kerala Tharippu Achuthsankar Novel set in 19th century Travancore Rashomon Agutagawa, Rayunosuki Stories translated from the Japanese by Rajan Thuvvara Balatkaram Cheyyappedunna Manass Airoor, Johnson Essay critical study of society's psychology frauds Bhakthiyum Kamavum Airoor, Johnson Essay a rationalist study into religions and their sexual motifs Hypnotism Oru Padanam Airoor, Johnson Essay rationalist and hypnotist on the science, illustrated with case studies Ormakkurippukal Ajitha Autobiographyformer Naxalite leader Aallkkoottam Anand Novel Vayalar Award winning writer Govardhanante Yatrakal Anand Novel a foray into mythology and history Marubhoomikal Undakunnath Anand Novel Vayalar Award winning work Agnisakshi Antharjanam, Lalithambika Novel made into a film by Syamaprasad Ormakallude Kudamaatom Anthicad, Sathyan Film autobiographical work of the filmmaker Sesham Vellithirayil Anthicad, Sathyan Autobiographybehind the scenes -

Current Affairs - 2018 Secretariat Asst Exam Special

CURRENT AFFAIRS - 2018 SECRETARIAT ASST EXAM SPECIAL GUIDANCE BUREAU CURRENT AFFAIRS CURRENTFOR SECRETARIAT AFFAIRS ASSt - EXAM2015 The Vayalar Award was instituted in 1977 in memory of the famous poet Vayalar Ramavarma (1928-1975) by the Vayalar Ramavarma Memorial Trust. This award is given for the best literary work in Malayalam, on October 27 (the death anniversary of Vayalar) every year. A sum of 1,00,000/-, a silver plate and certificate constitute the award. K.V. Mohan Kumar - the The first winner of the award was Lalithambika winner of the Vayalar Antharjanam for her work ‘Agnisakshi’ in 1977. Award for the year 2018 for his work ‘Ushnarashi’ 2016 U. K. Kumaran Thakshankunnu Swaroopam 2017 T. D. Ramakrishnan Sugandhi Enna Andal Devanayaki 2018 K.V. Mohan Kumar Ushnarashi Women Recipients of the Vayalar Award 1977 Lalithambika Antharjanam Agnisakshi 1984 Sugathakumari Ambalamani 1997 Madhavikutty (Kamala Surayya) Neermathalam Pootha Kalam 2004 Sarah Joseph Alahayude Penmakkal 2007 M. Leelavathy Appuvinte Anweshanam 2014 K.R.Meera Aarachaar CAREER GUIDANCE BUREAU 1 CURRENT AFFAIRS - 2018 SECRETARIAT ASST EXAM SPECIAL Vallathol Award is a literary award given by the Vallathol Sahithya Samithi for contribution to Malayalam literature. The award was instituted in 1991 in memory of Vallathol Narayana Menon, one of the modern triumvirate poets of Malayalam poetry. The award carries a cash prize of 1,11,111 and a citation. Pala Narayanan Nair was the first recipient of Vallathol Award in the year 1991. 2016 Sreekumaran Thampi 2017 Prabha Varma Pala Narayanan Nair 2018 M. Mukundan Prabha Varma The Ezhuthachan award is the highest literary honour that is given by the Kerala Sahitya Akademi, Government of Kerala. -

Malayalam Literary Awards and the List of Important Malayalam Literature Award Winners

Malayalam Literary Awards and the List of Important Malayalam Literature Award Winners Malayalam Literary Awards Important Malayalam Literary Awards Asan Poetry Prize Ayyappan Puraskaram Padmaprabha Literary Award Balamani Amma Award Lalithambika Antharjanam Smaraka Sahitya Award Padmarajan Award Basheer Award Malayattoor Award P. Kesavadev Literary Award Cherukad Award Mathrubhumi Literary P. Kunhiraman Nair Award Edasseri Award Award Thanima Puraskaram Ezhuthachan Award Muttathu Varkey Award Thakazhi Award Jnanpith Award Nooranad Haneef Award Thoppil Bhasi Award Kendra Sahitya Akademi Award Odakkuzhal Award Ulloor Award Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award O. N. V. Literary Award Vallathol Award Kadammanitta Ramakrishnan Award O. V. Vijayan Literary Award Vayalar Award Kamala Surayya Award Kendra Sahitya Akademi Award for Children's Literature (Bal Sahitya Puraskar) List of Important Malayalam Literature Award Winners Jnanpith Award Jnanapeedom Award is the most prestigious award among the literary awards in the country. It is presented by the Bharatiya Jnanpith to an author for their ‘outstanding contribution towards literature’. The awards were instituted in 1961, and is bestowed only on Indian writers writing in Indian languages. The first recipient of the award was the Malayalam writer G. Sankara Kurup, in 1965 for his collection of poems, Odakkuzhal. And, the first woman writer to recieve this award was Ashapoorna Devi, a Bengali writer, in 1976. The prize money for the Jnanpith Award is Rs. 11 lakh and a bronze replica of Hindu Goddess Saraswati. Jnanpith Award - Malayali Award Winner Lists Year Awardee Literary Works 1965 G. Sankara Kurup Odakkuzhal 1980 S. K. Pottekkatt Oru Desathinte Katha 1984 Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai Kayar 1995 M. T. Vasudevan Nair Overall Contribution For Overall contribution to 2007 O. -

Annex B India

WP1_Annex B_India Annex B Methodological justification and design Methodology In this paper three types of communication mediums are analyzed: cinema, short stories and proverbs. This section details the importance of each of these mediums to understand Indian culture related to understand the relationship between shame and poverty. 1. Cinema Cinema as an art form, with an aim of popular entertainment and method of education, began at the end of 19th century. Cinema is one of the best cultural artifacts for understanding a given society since it employs the technique of mixing moving pictures and voice (transforming the earlier version of drama) through “entertainment, offering stories, spectacles, music, drama, humour and technical tricks for popular consumption” (McQuail, 2005). All over the world around 4000 films are being produced every year. India dominates the scenario with an average of 700 films per year since 1970s, when the cinema revolution began in India (though the first cinema was produced in 1913). In 2009 India produced close to 3000 films. The majority of the films produced in India are in South Indian languages, especially, Malayalam, Tamil and Telugu. However, Hindi, being the national language takes the largest box office hit. The dramatic and persistent growth of cinema culture in India is particularly because of the ‘viewing’ culture among Indian population. Film critics have criticized the homogenous classification of ‘Indian cinema’, and rightly pointed out the existence of culturally located cinema productions of at least 24 Indian languages. This aspect is important while constructing culturally shaped notion of shame. This multiplicity of languages and cultures poses a major challenge for selecting and studying Indian cinema. -

Kerala History

Kerala History Fill in the Blanks 13. The highest rainfall in Kerala 26. Kollam Era began in .......... is at .......... 27. .......... was the capital of Venad 1. The first Hydro-electric 14. The first newspaper in Kerala Kingdom. project of Kerala is .......... is .......... 28. The first Jewish Synagogue 2. The river mentioned in 15. The most scientific and the in Asia was set up in .......... in Kautilya’s Arthasasthra is most elaborately redefined 1350. dance form of Kerala is .......... .......... 29. The first Mamankom was 3. The founder of the Second 16. The ‘Wagon Tragedy’ in held in .......... Malabar was in the year .......... Chera Empire was .......... 30. Vasco da Gama landed with 17. The Srimoolam Prajasabha 4. The author of “Avantisun- his companies at Kappad, was established in Travan- dari Kathasara” is .......... north of Calicut, on .......... core in .......... 5. The most important event in 31. .......... was the first portuguese the history of the Kerala 18. ‘Battle of Kulachal’ was fought in the year .......... viceroy in Kerala. Church in the Portuguese 32. .......... was the capital of period was .......... 19. Kundara Proclamation was issued by Velu Thampi in the Kulashekharas. 6. The ancient plant encyclo- year .......... 33. The emperor of Kulasekhara paedia ‘Hortus Malabaricus’ Kingdom was known as .......... was written by the .......... 20. The first private hydro- electric power project is 34. .......... written by clement 7. The integration of Travancore situated at .......... piyannus Pathiri, which was and Cochin took place in the year .......... 21. The only Malayalee President published in 1772, was the of the Indian National first book in Malayalam. 8. The first Malayalam Congress was ......... -

The Country and the Village: Representations of the Rural in Twentieth-Century South Asian Literatures

THE COUNTRY AND THE VILLAGE: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE RURAL IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY SOUTH ASIAN LITERATURES by Anupama Mohan A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English and the Collaborative Program in South Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Anupama Mohan (2010) THE COUNTRY AND THE VILLAGE: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE RURAL IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY SOUTH ASIAN LITERATURES Anupama Mohan Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English and the Collaborative Program in South Asian Studies University of Toronto 2010 ABSTRACT Twentieth-century Indian and Sri Lankan literatures (in English, in particular) have shown a strong tendency towards conceptualising the rural and the village within the dichotomous paradigms of utopia and dystopia. Such representations have consequently cast the village in idealized (pastoral) or in realist (counter-pastoral/dystopic) terms. In Chapters One and Two, I read together Mohandas Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj (1908) and Leonard Woolf’s The Village in the Jungle (1913) and argue that Gandhi and Woolf can be seen at the head of two important, but discrete, ways of reading the South Asian village vis-à-vis utopian thought, and that at the intersection of these two ways lies a rich terrain for understanding the many forms in which later twentieth-century South Asian writers chose to re-create city-village-nation dialectics. In this light, I examine in Chapter Three the work of Raja Rao ( Kanthapura , 1938) and O. V. Vijayan ( The Legends of Khasak , 1969) and in Chapter Four the writings of Martin Wickramasinghe ( Gamperaliya , 1944) and Punyakante Wijenaike ( The Waiting Earth , 1966) as providing a re-visioning of Gandhi’s and Woolf’s ideas of the rural as a site for civic and national transformation.