Vaikom Muhammad Basheer and Indian Literature Author(S): K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Love and Marriage Across Communal Barriers: a Note on Hindu-Muslim Relationship in Three Malayalam Novels

Love and Marriage Across Communal Barriers: A Note on Hindu-Muslim Relationship in Three Malayalam Novels K. AYYAPPA PANIKER If marriages were made in heaven, the humans would not have much work to do in this world. But fornmately or unfortunately marriages continue to be a matter of grave concern not only for individuals before, during, and/ or after matrimony, but also for social and religious groups. Marriages do create problems, but many look upon them as capable of solving problems too. To the poet's saying about the course of true love, we might add that there are forces that do not allow the smooth running of the course of true love. Yet those who believe in love as a panacea for all personal and social ills recommend it as a sure means of achieving social and religious integration across caste and communal barriers. In a poem written against the backdrop of the 1921 Moplah Rebellion in Malabar, the Malayalam poet Kumaran Asan presents a futuristic Brahmin-Chandala or Nambudiri-Pulaya marriage. To him this was advaita in practice, although in that poem this vision of unity is not extended to the Muslims. In Malayalam fi ction, however, the theme of love and marriage between Hindus and Muslims keeps recurring, although portrayals of the successful working of inter-communal marriages are very rare. This article tries to focus on three novels in Malayalam in which this theme of Hindu-Muslim relationship is presented either as the pivotal or as a minor concern. In all the three cases love flourishes, but marriage is forestalled by unfavourable circumstances. -

List of Books 2018 for the Publishers.Xlsx

LIST I LIST OF STATE BARE ACTS TOTAL STATE BARE ACTS 2018 PRICE (in EDITION SL.No. Rupees) COPIES AUTHOR/ REQUIRED PRICE FOR EDN / YEAR PUBLISHER EACH COPY APPROXIMATE K.G. 1 Abkari Laws in Kerala Rajamohan/Ar latest 898 5 4490 avind Menon Govt. 2 Account Code I Kerala latest 160 10 1600 Publication Govt. 3 Account Code II Kerala latest 160 10 1600 Publication Suvarna 4 Advocates Act latest 790 1 790 Publication Advocate's Welfare Fund Act George 5 & Rules a/w Advocate's Fees latest 120 3 360 Johnson Rules-Kerala Arbitration and Conciliation 6 Rules (if amendment of 2016 LBC latest 80 5 400 incorporated) Bhoo Niyamangal Adv. P. 7 latest 1500 1 1500 (malayalam)-Kerala Sanjayan 2nd 8 Biodiversity Laws & Practice LBC 795 1 795 2016 9 Chit Funds-Law relating to LBC 2017 295 3 885 Chitty/Kuri in Kerala-Laws 10 N Y Venkit 2012 160 1 160 on Christian laws in Kerala Santhosh 11 2007 520 1 520 Manual of Kumar S Civil & Criminal Laws in 12 LBC 2011 250 1 250 Practice-A Bunch of Civil Courts, Gram Swamy Law 13 Nyayalayas & Evening 2017 90 2 180 House Courts -Law relating to Civil Courts, Grama George 14 Nyayalaya & Evening latest 130 3 390 Johnson Courts-Law relating to 1 LIST I LIST OF STATE BARE ACTS TOTAL STATE BARE ACTS 2018 PRICE (in EDITION SL.No. Rupees) COPIES AUTHOR/ REQUIRED PRICE FOR EDN / YEAR PUBLISHER EACH COPY APPROXIMATE Civil Drafting and Pleadings 15 With Model / Sample Forms LBC 2016 660 1 660 (6th Edn. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

MTS EXAMINATION 2015 -16 Class : X QUESTION PAPER 10 Score : 400 Register No : Time : 2 Hrs

MTS EXAMINATION 2015 -16 Class : X QUESTION PAPER 10 Score : 400 Register No : Time : 2 hrs General Instructions 1. Candidates are supplied with an OMR Answer Sheet. 2. Answer the questions in the OMR Sheet by shading the appropriate bubble. 3. Shade the bubbles with black ball point pen. 4. Each question carries four marks. One mark will be deducted for each wrong answer. 5. Use the space provided in the last page for rough work. Read the passage and answer the questions from 1 to 4. For many years, the continent Africa remained unexplored and unknown. The main reason was the inaccessibility to its interior region due to dense forests, wild life, savage tribals, de- serts and barren solid hills. Many people who tried to explore the land could not survive the dangers. David Livingstone is among those brave few who not only explored part of Africa but also lived among the tribals bringing them near to Social Milieu. While others explored with the idea of expanding their respective empires. Livingstone did so to explore its vast and mysteri- ous hinterland, rivers and lakes. He was primarily a religious man and a medical practitioner who tried to help mankind with it. Livingstone was born in Scotland and was educated to become a doctor and priest. His exploration started at the beginning of the year 1852. He ex- plored an unknown river in Western Luanda. However, he was reduced to a skeleton during four years of travelling. By this time, he had become famous and when he returned to England for convalescing, entire London along with Queen Victoria turned to welcome him. -

Library Stock.Pdf

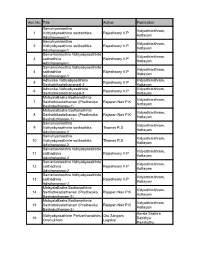

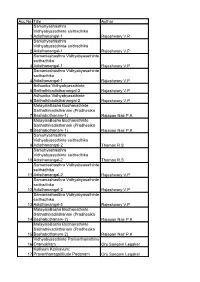

Acc.No. Title Author Publication Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 1 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 2 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 3 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 4 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 5 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 6 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 7 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 8 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 9 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 10 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 11 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 12 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 13 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 14 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-2) MalayalaBasha -

Feminism and Representation of Women Identities in Indian Cinema: a Case Study

FEMINISM AND REPRESENTATION OF WOMEN IDENTITIES IN INDIAN CINEMA: A CASE STUDY Amaljith N.K1 Manonmaniam Sundaranar University, India. Abstract The film is one of the most popular sources of entertainment worldwide. Plentiful films are produced each year and the amount of spectators is also huge. Films are to be called as the mirror of society, because they portray the actual reality of the society through the cinematography. Thus, cinema plays an essential role in shaping views about, caste, creed and gender. There are many pieces of research made on the representation of women or gender in films. But, through this research, the researcher wants to analyse in- depth about the character representation of women in the Malayalam film industry how strong the so-called Mollywood constructs the strongest and stoutest women characters in Malayalam cinema in the 21st-century cinema. This study confers how women are portrayed in the Malayalam cinema in the 21st century and how bold and beautiful are the women characters in Malayalam film industry are and how they act and survive the social stigma and stereotypes in their daily life. All sample films discuss the plights and problems facing women in contemporary society and pointing fingers towards the representation of women in society. The case study method is used as the sole Methodology for research. And Feminist Film theory and theory of patriarchy applied in the theoretical framework. Keywords: Gender, Women, Film, Malayalam, Representation, Feminism. Feminismo e representação da identidade de mulheres no cinema indiano: um estudo de caso Resumo O filme é uma das fontes de entretenimento mais populares em todo o mundo. -

English Books in Ksa Library

Author Title Call No. Moss N S ,Ed All India Ayurvedic Directory 001 ALL/KSA Jagadesom T D AndhraPradesh 001 AND/KSA Arunachal Pradesh 001 ARU/KSA Bullock Alan Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thinkers 001 BUL/KSA Business Directory Kerala 001 BUS/KSA Census of India 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 1 - Kannanore 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 9 - Trivandrum 001 CEN/KSA Halimann Martin Delhi Agra Fatepur Sikri 001 DEL/KSA Delhi Directory of Kerala 001 DEL/KSA Diplomatic List 001 DIP/KSA Directory of Cultural Organisations in India 001 DIR/KSA Distribution of Languages in India 001 DIS/KSA Esenov Rakhim Turkmenia :Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union 001 ESE/KSA Evans Harold Front Page History 001 EVA/KSA Farmyard Friends 001 FAR/KSA Gazaetteer of India : Kerala 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India 4V 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India : kerala State Gazetteer 001 GAZ/KSA Desai S S Goa ,Daman and Diu ,Dadra and Nagar Haveli 001 GOA/KSA Gopalakrishnan M,Ed Gazetteers of India: Tamilnadu State 001 GOP/KSA Allward Maurice Great Inventions of the World 001 GRE/KSA Handbook containing the Kerala Government Servant’s 001 HAN/KSA Medical Attendance Rules ,1960 and the Kerala Governemnt Medical Institutions Admission and Levy of Fees Rules Handbook of India 001 HAN/KSA Ker Alfred Heros of Exploration 001 HER/KSA Sarawat H L Himachal Pradesh 001 HIM/KSA Hungary ‘77 001 HUN/KSA India 1990 001 IND/KSA India 1976 : A Reference Annual 001 IND/KSA India 1999 : A Refernce Annual 001 IND/KSA India Who’s Who ,1972,1973,1977-78,1990-91 001 IND/KSA India :Questions -

A Study on Time by Mtvasudevan Nair

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 07, Issue 07, 2020 Socio-Cultural Transformation: A Study On Time By M.T.Vasudevan Nair Dr. Digvijay Pandya1, Ms. Devisri B2 1Associate Professor, Department of English, Lovely Professional University, Punjab, India. 2Doctoral Research Scholar, Department of English, Punjab, India. ABSTRACT: Kerala, the land is blessed with nature and its tradition. It has a copiously diverse vegetation beautiful landscape and climate. The land is also rich in its literature. M.T.Vasudevan Nair is one of the renowned figures in Malayalam literature who excels and portrays the traditional and cultural picture of Kerala society. Kaalam, published in 1969 is a lyrical novel in Malayalam literature by M.T.Vasudevan Nair and Gita Krishnan Kutty translates it into English as Time. This paper tries to analyse the sociological and cultural transformation of Kerala in the novel Time during the period of MT. It also focuses on the system of Marumakkathayam,joint family system and its transformation. Keywords: Sociological and Cultural transformation, Marumakkathayam, Joint family system, Tarawads. India is a multi-lingual country steeped in its rich culture and tradition. There are many such treasure troves of creativity in the regional languages that would have been lost to the rest of the world, but for its tradition, which is the only means to reach a wider group of reading public. Tradition helps to understand the thought process of the people of a particular region against the backdrop of socio-cultural roots. Malayalam is one of the multifaceted languages in India. Malayalam, the mother tongue of nearly thirty million Malayalis, ninety percent of whom living in Kerala state in the south – west corner of India, belongs to the Dravidian family of languages. -

Syllabus of MA(CSS) English Language and Literature

INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH Syllabus MA (CSS) English Language and Literature 1 Syllabus Core Courses Semester I ENG 511 Chaucer to the Augustan Age ENG 512 Shakespeare ENG 513 Romantics and Victorians Semester II ENG 521 The Twentieth Century ENG 522 American Literature ENG 523 Literary Theory I Semester III ENG 531 Indian writing In English ENG 532 Contemporary Literature in English ENG 533 Literary Theory II Semester IV ENG 541 Linguistics ENG 542 English language Teaching ENG 543 Cultural Studies ENG 544 Keralam : History, Culture and Literature. 2 Institute of English, University of Kerala MA (CSS) Degree Course in English Language and Literature ENG 511 – Chaucer to the Augustan Age Semester: One Credits: Four Instructors: Dr. Maya Dutt Vishnu Narayanan Aim of the course The course aims at providing a comprehensive introduction to English Literature starting from the Age of Chaucer to the Neoclassical Age with reference to the origin and development of English Poetry, Drama, Prose and fiction. The twentieth century critical responses to the writings of the age are also given importance in the course. Course Description 1. Socio-political background of Chaucer’s Age 2. The Renaissance in England 3. Ballads and sonnets – Wyatt, Surrey, Sidney, Spenser 4. Metaphysical poetry – Donne, Herbert, Vaughan, Marvell 5. The development of prose – More, Sidney, Bacon, Browne, Isaac Walton, Thomas Hobbes 6. The rise of English drama – Miracle plays, Morality plays, Interlude,Revenge tragedy. 7. University Wits – Ben Jonson – Comedy of Humours 8. Jacobean drama – Webster, Beaumont and Fletcher, Massinger, Dekker 9. The Reformation 10. Milton – life and works 11. The Restoration 12. -

Acc.No. Title

Acc.No. Title Author Samuhyashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 1 Adisthanangal-1 Rajeshwary V.P Samuhyashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 2 Adisthanangal-1 Rajeshwary V.P Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 3 Adisthanangal-1 Rajeshwary V.P Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 4 Adisthanangal-1 Rajeshwary V.P Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte 5 Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Rajeshwary V.P Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte 6 Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Rajeshwary V.P MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika 7 Bashabothanam-1) Rajapan Nair P.K MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika 8 Bashabothanam-1) Rajapan Nair P.K Samuhyashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 9 Adisthanangal-2 Thomas R.S Samuhyashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 10 Adisthanangal-2 Thomas R.S Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 11 Adisthanangal-2 Rajeshwary V.P Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 12 Adisthanangal-2 Rajeshwary V.P Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika 13 Adisthanangal-2 Rajeshwary V.P MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika 14 Bashabothanam-2) Rajapan Nair P.K MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika 15 Bashabothanam-2) Rajapan Nair P.K Vidhyabyasathinte Parivarthanathinu 16 Oramukham Oru Sangam Legakar Kalliyum Kariyavum: 17 Pravarthanagallillude Padanam Oru Sangam Legakar MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika 18 Bashabothanam-2) Rajapan Nair P.K Adhunika Vidhyabyasaprakriya: 19 Vikasanavum Pravannathakallum Sivarajan -

Books & Authors

BOOKS & AUTHORS I. Alphabetical Listing of Books: A A Backward Place : Ruth Prawer Jhabwala A Bend in the Ganges : Manohar Malgonkar A Bend in the River : V. S. Naipaul A Billion is Enough : Ashok Gupta A Bride for the Sahib and Other Stories : Khushwant Singh A Brief History of Time : Stephen Hawking A Brush with Life : Satish Gujral A Bunch of Old Letters : Jawaharlal Nehru A Cabinet Secretary Looks Back : B. G. Deshmukh . A Call To Honour-In Service of Emergent India : Jaswant Singh A Captain's Diary : Alec Stewart A China Passage : John Kenneth Galbraith A Conceptual Encyclopaedia of Guru Gtanth Sahib : S. S. Kohli A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy : Karl Marx A Critique of Pure Reason : Immanuel Kant A Dangerous Place : Daniel Patrick Moynihan A Doctor's Story of Life and Death : Dr. Kakkana Subbarao & Arun K. Tiwari A Doll's House : Henrik Ibsen A Dream in Hawaii : Bhabani Bhattacharya A Farewell to Arms : Ernest Hemingway A Fine Balance : Rohinton Mistry A Foreign Policy for India : I. K. Gujral A Gift of Wings : Shanthi Gopalan A Handful of Dust : Evelyn Waugh A Himalayan Love Story : Namita Gokhale A House Divided : Pearl S. .Buck A Judge's Miscellany : M. Hidayatullah A Last Leap South : Vladimir Zhirinovsky A Long Way : P. V. Narasimha Rao A Man for All Seasons : Robert Bolt A Midsummer Night's Dream : William Shakespeare A Million Mutinies Now : V. S. Naipaul A New World : Amit Chaudhuri A Pair of Blue Eyes : Thomas Hardy A Passage to England : Nirad C. Chaudhuri A Passage to India : E. -

Chapter- V Representation of Social Change in Kayar: a Historical Analysis

CHAPTER- V REPRESENTATION OF SOCIAL CHANGE IN KAYAR: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS As elsewhere in the colonial societies, interaction between the structures of domination institutionalized by colonialism and the ways in which indigenous responses to it were evolved forms the central theme of the social history of the modern Malayali society as well. During the post-colonial phase, once the tumultuousness of the anti- colonial political struggles got subsided, and the society moved on to the specific historical juncture of nation building, there developed a literary trend in the Malayalam literary arena of presenting the history of social change (modernization as a social experience that the various localized popular communities had undergone) through story narratives. On account of its vastness and elasticity, novel proved to be the most preferred format for epitomizing the convergence of history and literature on the theme of social change. The novel Kayar by Takazhi Sivasankara Pillai published in 1978 presents the trajectory of the historical development of the modern society in Travancore. As has been mentioned, this novel has been conceived as a narrative depicting the transformation process in all the diverse aspects of life in a particular region, the Takazhi village, the author’s own provenance and its immediate neighborhood in Kuttanad from the nineteenth century colonial situation to the introduction of land reforms in the democratic era during the early 1970s. As an addendum to the juxtaposition of the literary and historical representations of the social change process, this section seeks to make a historical analysis of the same accomplished in the Kayar narrative.