The Train That Had Wings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Synonym to Conservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage: Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture, Heading for Its 30Th Anniversary

A Synonym to Conservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage: Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture, Heading for Its 30th Anniversary V. Jayarajan Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture is an institution that was first registered on December 20, 1989 under the Societies Registration Act of 1860, vide No. 406/89. Over the last 16 years, it has passed through various stages of growth, especially in the fields of performance, production, documentation, and research, besides the preservation of folk art and culture. Since its inception in 1989, Folkland has passed through various phases of growth into a cultural organization with a global presence. As stated above, Folkland has delved deep into the fields of stage performance, production, documentation, and research, besides the preservation of folk art and culture. It has strived hard and treads the untrodden path with a clear motto of preservation and inculcation of old folk and cultural values in our society. Folkland has a veritable collection of folk songs, folk art forms, riddles, fables, myths, etc. that are on the verge of extinction. This collection has been recorded and archived well for scholastic endeavors and posterity. As such, Folkland defines itself as follows: 1. An international center for folklore and culture. 2. A cultural organization with clearly defined objectives and targets for research and the promotion of folk arts. Folkland has branched out and reached far and wide into almost every nook and corner of the world. The center has been credited with organizing many a festival on folk arts or workshop on folklore, culture, linguistics, etc. -

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

Vaikom Muhammad Basheer and Indian Literature Author(S): K

Sahitya Akademi Vaikom Muhammad Basheer and Indian Literature Author(s): K. Satchidanandan Source: Indian Literature, Vol. 53, No. 1 (249) (January/February 2009), pp. 57-78 Published by: Sahitya Akademi Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23348483 Accessed: 25-03-2020 10:34 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Sahitya Akademi is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Indian Literature This content downloaded from 103.50.151.143 on Wed, 25 Mar 2020 10:34:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A BIRTH CENTENARY TRIBUTE Vaikom Muhammad Basheer and Indian Literature K. Satchidanandan I Vaikom like Muhammadto call the democratic Basheer tradition (1908-1994) in Indian belongsliterature, firmly a living tradition to what I that can be traced back to the Indian tribal lore including the Vedas and the folktales and fables collected in Somdeva's Panchatantra and Kathasaritsagar, Gunadhya's Brihatkatha, Kshemendra's Brihatkathamanjari, the Vasudeva Hindi and the Jatakas. This tradition was further enriched by the epics, especially Ramayana and Mahabharata that combined several legends from the oral tradition and are found in hundreds of oral, performed and written versions across the nation that interpret the tales from different perspectives of class, race and gender and with different implications testifying to the richness and diversity of Indian popular imagination and continue to produce new textual versions, including dalit, feminist and other radical interpretations and adaptations even today. -

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT History Ponnani Is Popularly Known As “The Mecca of Kerala”

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT HISTORY Ponnani is popularly known as “the Mecca of Kerala”. As an ancient harbour city, it was a major trading hub in the Malabar region, the northernmost end of the state. There are many tales that try to explain how the place got its name. According to one, the prominent Brahmin family of Azhvancherry Thambrakkal once held sway over the land. During their heydays, they offered ponnu aana [elephants made of gold] to the temples, and this gave the land the name “Ponnani”. According to another, due to trade, ponnu [gold] from the Arab lands reached India for the first time at this place, and thus caused it to be named “Ponnani”. It is believed that a place that is referred to as “Tyndis” in the Greek book titled Periplus of the Erythraean Sea is Ponnani. However historians have not been able to establish the exact location of Tyndis beyond doubt. Nor has any archaeological evidence been recovered to confirm this belief. Politically too, Ponnani had great importance in the past. The Zamorins (rulers of Calicut) considered Ponnani as their second headquarters. When Tipu Sultan invaded Kerala in 1766, Ponnani was annexed to the Mysore kingdom. Later when the British colonized the land, Ponnani came under the Bombay Province for a brief interval of time. Still later, it was annexed Malabar and was considered part of the Madras Province for one-and-a-half centuries. Until 1861, Ponnani was the headquarters of Koottanad taluk, and with the formation of the state of Kerala in 1956, it became a taluk in Palakkad district. -

Love and Marriage Across Communal Barriers: a Note on Hindu-Muslim Relationship in Three Malayalam Novels

Love and Marriage Across Communal Barriers: A Note on Hindu-Muslim Relationship in Three Malayalam Novels K. AYYAPPA PANIKER If marriages were made in heaven, the humans would not have much work to do in this world. But fornmately or unfortunately marriages continue to be a matter of grave concern not only for individuals before, during, and/ or after matrimony, but also for social and religious groups. Marriages do create problems, but many look upon them as capable of solving problems too. To the poet's saying about the course of true love, we might add that there are forces that do not allow the smooth running of the course of true love. Yet those who believe in love as a panacea for all personal and social ills recommend it as a sure means of achieving social and religious integration across caste and communal barriers. In a poem written against the backdrop of the 1921 Moplah Rebellion in Malabar, the Malayalam poet Kumaran Asan presents a futuristic Brahmin-Chandala or Nambudiri-Pulaya marriage. To him this was advaita in practice, although in that poem this vision of unity is not extended to the Muslims. In Malayalam fi ction, however, the theme of love and marriage between Hindus and Muslims keeps recurring, although portrayals of the successful working of inter-communal marriages are very rare. This article tries to focus on three novels in Malayalam in which this theme of Hindu-Muslim relationship is presented either as the pivotal or as a minor concern. In all the three cases love flourishes, but marriage is forestalled by unfavourable circumstances. -

1 ; Mahatma Gandhi University B. A. Music Programme(Vocal

1 ; MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. A. MUSIC PROGRAMME(VOCAL) COURSE DETAILS Sem Course Title Hrs/ Cred Exam Hrs. Total Week it Practical 30 mts Credit Theory 3 hrs. Common Course – 1 5 4 3 Common Course – 2 4 3 3 I Common Course – 3 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 1 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 1 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 1 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 4 5 4 3 Common Course – 5 4 3 3 II Common Course – 6 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 2 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 2 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 2 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 7 5 4 3 Common Course – 8 5 4 3 III Core Course – 3 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 4 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 3 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 3 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 9 5 4 3 Common Course – 10 5 4 3 IV Core Course – 5 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 6 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 4 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 4 (Theory) 2 2 3 Core Course – 7 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 8 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts V Core Course – 9 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 10 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Open Course – 1 (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 1 2 1 Core Course – 11 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 12 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts VI Core Course – 13 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 14 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Elective (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 2 2 1 Total 150 120 120 Core & Complementary 104 hrs 82 credits Common Course 46 hrs 38 credits Practical examination will be conducted at the end of each semester 2 MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Music in South India – Kerala a Smithsonian Folkways Lesson Designed By: Lum Chee Hoo University of Washington

Music in South India – Kerala A Smithsonian Folkways Lesson Designed by: Lum Chee Hoo University of Washington Summary: Talk about the geography, language, and culture of Kerala in South India using story songs, dance dramas, and rhythms. Introduce students to specific artists and instruments important to Kerala's musical traditions. Suggested Grade Levels: 9-12 Country: India Region: Asia Culture Group: Kerala Genre: Indian Instruments: Voice Language: Malayalam Co-Curricular Areas: Social Studies National Standards: 6, 9 Prerequisites: None Objectives: Learn about culture of Kerala group, including music, dance, and language Materials: “Idakka” from Music from South India- Kerala (FW04365) http://www.folkways.si.edu/tr-ankaran-nambudiri-and-pm-narayana- mara/idakka/world/music/track/smithsonian “Nala Charitam,” Music from South India- Kerala (FW04365) http://www.folkways.si.edu/mep-pillai-and-gopinathan-nayar-k-damodaran- pannikar-and-vasudeva-poduwal-mankulam-vishnu-nambudiri-and-kudama-ur- karunakaran-nayar/kathakai-nala-charitam/world/music/track/smithsonian “Panchawadyam” from Music from South India- Kerala (FW04365) http://www.folkways.si.edu/instrumental/panchawadyam/world/music/track/s mithsonian http://www.folkways.si.edu/narayana-mara-and- party/panchawadyam/world/music/track/smithsonian Liner notes from Music from South India- Kerala (FW04365) http://media.smithsonianfolkways.org/liner_notes/folkways/FW04365.pdf The JVC video anthology of world music and dance: South Asia I, India, Track 11- 2 (Kathakali-dance-drama: Dryodana vadham from the Mohabharata DVD - Vanaprastham: The last dance (1999). Director: Shaji N. Karun. Vanguard Cinema. ASIN: B000066C7A Map of South India Pictures of instruments: from liner notes and Music in South India: Experiencing music, expressing culture Lesson Segments: 1. -

Marxist Praxis: Communist Experience in Kerala: 1957-2011

MARXIST PRAXIS: COMMUNIST EXPERIENCE IN KERALA: 1957-2011 E.K. SANTHA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SIKKIM UNIVERSITY GANGTOK-737102 November 2016 To my Amma & Achan... ACKNOWLEDGEMENT At the outset, let me express my deep gratitude to Dr. Vijay Kumar Thangellapali for his guidance and supervision of my thesis. I acknowledge the help rendered by the staff of various libraries- Archives on Contemporary History, Jawaharlal Nehru University, C. Achutha Menon Study and Research Centre, Appan Thampuran Smaraka Vayanasala, AKG Centre for Research and Studies, and C Unniraja Smaraka Library. I express my gratitude to the staff at The Hindu archives and Vibha in particular for her immense help. I express my gratitude to people – belong to various shades of the Left - who shared their experience that gave me a lot of insights. I also acknowledge my long association with my teachers at Sree Kerala Varma College, Thrissur and my friends there. I express my gratitude to my friends, Deep, Granthana, Kachyo, Manu, Noorbanu, Rajworshi and Samten for sharing their thoughts and for being with me in difficult times. I specially thank Ugen for his kindness and he was always there to help; and Biplove for taking the trouble of going through the draft intensely and giving valuable comments. I thank my friends in the M.A. History (batch 2015-17) and MPhil/PhD scholars at the History Department, S.U for the fun we had together, notwithstanding the generation gap. I express my deep gratitude to my mother P.B. -

Re-Mapping Identity, Culture and History Through Literature , Published by Veda Publications Is a Collection Of

Re-Mapping Identity, Culture and History through Literature Editors : Dr. Sushil Mary Mathews Dr. M. Angeline RE-MAPPING IDENTITY, CULTURE AND HISTORY THROUGH LITERATURE Editors : Dr. Sushil Mary Mathews, Dr. M. Angeline Published by VEDA PUBLICATIONS Address : 45-9-3, Padavalarevu, Gunadala, Vijayawada. 520004, A.P. INDIA. Mobile : +91 9948850996 Web : www.vedapublications.com / www.joell.in Copyright © 2019 Publishing Process Manager : K.John Wesley Sasikanth First Published : August 2019, Printed in India E-ISBN : 978-93-87844-18-6 For copies please contact : [email protected] Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in the book are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. © All Rights reserved, no part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. Foreword I am extremely delighted to note that the Department of English is bringing out a book on relevant issues relating to Remapping Identity, Culture and History through Literature in collusion with Veda Publications. The essays by erudite academicians and research scholars probe deeply into assorted aspects of modern global issues of Identity, Culture and History, a multidisciplinary perspective. This book deals with cross references that connect Literature with Culture and History of various works of authors dealing with cultural aspects and Identity crisis globally. Diversified poems, novels and plays written by authors throw light on the current burning issue of diaspora and cultural conflicts. The younger generation will glean awareness on various sensitive issues like marginalization and trauma of migration that confronts people today. I am sure this book will give numerous ideas which will be an eye opener to many issues through a plethora of literary genres. -

MTS EXAMINATION 2015 -16 Class : X QUESTION PAPER 10 Score : 400 Register No : Time : 2 Hrs

MTS EXAMINATION 2015 -16 Class : X QUESTION PAPER 10 Score : 400 Register No : Time : 2 hrs General Instructions 1. Candidates are supplied with an OMR Answer Sheet. 2. Answer the questions in the OMR Sheet by shading the appropriate bubble. 3. Shade the bubbles with black ball point pen. 4. Each question carries four marks. One mark will be deducted for each wrong answer. 5. Use the space provided in the last page for rough work. Read the passage and answer the questions from 1 to 4. For many years, the continent Africa remained unexplored and unknown. The main reason was the inaccessibility to its interior region due to dense forests, wild life, savage tribals, de- serts and barren solid hills. Many people who tried to explore the land could not survive the dangers. David Livingstone is among those brave few who not only explored part of Africa but also lived among the tribals bringing them near to Social Milieu. While others explored with the idea of expanding their respective empires. Livingstone did so to explore its vast and mysteri- ous hinterland, rivers and lakes. He was primarily a religious man and a medical practitioner who tried to help mankind with it. Livingstone was born in Scotland and was educated to become a doctor and priest. His exploration started at the beginning of the year 1852. He ex- plored an unknown river in Western Luanda. However, he was reduced to a skeleton during four years of travelling. By this time, he had become famous and when he returned to England for convalescing, entire London along with Queen Victoria turned to welcome him. -

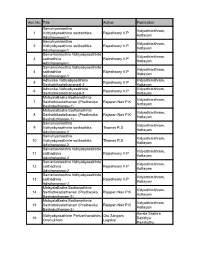

Library Stock.Pdf

Acc.No. Title Author Publication Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 1 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 2 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 3 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 4 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 5 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 6 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 7 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 8 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 9 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 10 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 11 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 12 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 13 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 14 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-2) MalayalaBasha