Surface Velar Palatalization in Polish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

External Sandhi in L2 Segmental Phonetics – Final (De)Voicing in Polish English

Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Acquisition of Second Language Speech Concordia Working Papers in Applied Linguistics, 5, 2014 © 2014 COPAL External Sandhi in L2 Segmental Phonetics – Final (De)Voicing in Polish English Geoffrey Schwartz Anna Balas Arkadiusz Rojczyk Adam Mickiewicz University Adam Mickiewicz University University of Silesia Abstract The effects of external sandhi, phonological processes that span word boundaries, have been largely neglected in L2 speech research. The glottalization of word‐initial vowels in Polish may act as a “sandhi blocker” that prevents the type of liaison across word boundaries that is common in English (e.g. find out/fine doubt). This reinforces the context for another process, final obstruent devoicing, which is typical of Polish‐accented English. Clearly ‘initial’ and ‘final’ do not mean the same thing for the phonologies of the two languages. An adequate theory of phonological representation should be able to express these differences. This paper presents an acoustic study of the speech of voiced C#V sequences in Polish English. Results show that the acquisition of liaison, which entails suppression of the L1 vowel‐initial glottalization process, contributes to the error‐free production of final voiced obstruents, implying the internalization of cross‐language differences in boundary representation. Although research into the acquisition of second language (L2) speech has flourished in recent years, a number of areas remain to be explored. External sandhi, phonological processes that span word boundaries, constitute one such uncharted territory in L2 speech research. In what Geoffrey Schwartz, Anna Balas & Arkadiusz Rojczyk 638 follows we will briefly review some existing L2 sandhi research. -

Ankes Drejtuar TAP

Ankes drejtuar TAP Ngjeli Komini August 31, 2016 Une i nenshkruari Ngjeli Toli Komini, me banim ne fshatin Konezbalt, rethi Berat dhe nr telefoni , ju drejtohem me ane te kesaj ankese faktet e ceshtjes: Une Ngjeli Komini jam Indetifikuar si person i prekur nga gazsjellesi TAP. Kam ne pronesi nje parcel me nr535./ 10 me nje sip 2800m2 nga kjo siperfaqe 1937.95 m2 do te me okupohen nga TAP. Kete sip e kam te mbjell vresht (rrush) i cili ne momentin qe nuk kan filluar akoma punimet po shkon ne vitin e 5-ste (peste) dhe per kete siperfaqe me eshte ofruar ne kontraten e pare nje shume si me posht: Per qeran e sip 1937.95m 401 156.77 LEK per kompesimin e servitutit me sip 149.67m2 eshte 61 963.50 LEK per kompesimin e te mbjellave per te cilen une bej kete ankes jam vleresuar per vreshtim me rush ne vleren 479 624.32 LEK. Vreshti im po shkon ne vitin e 5 dhe vleresohet me shumen si ne vitin e 2 te mbjelljes. Pretendimet e mia jan keto: shume kompesime nuk mbulon harxhimet qe une kam bere per ta sjell kete vresht ne vitin e peste dhe nuk do te me kompesoj prodhimin qe une do merrja per 2 vjet qe ai eshte ne perdorim nga TAP. Ketij vreshti do ti nevojiten dhe 5 vjet te tjera te vij ne kete gjendje prodhimi: TAP-i sot po ma prish; dhe tjetra eshte qe une nuk mund ta mbjell me vresht mbi servitut qe eshte nje sip prej 149.95 m kam mar 2 vlera te ndryshme per te njejten parcel e dyta me e ulet se e para. -

ZAS Papers in Linguistics

Zentrum für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft, Sprachtypologie und Universalienforschung . ZAS Papers in Linguistics Volume 19 December 2000 Edited by EwaldLang Marzena Rochon Kerstin Schwabe I! Oliver Teuber ISSN 1435-9588 Investigations in Prosodie Phonology: The Role of the Foot and the Phonologieal Word Edited by T. A. Hall University of Leipzig Marzena Rochon Zentrum für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft, Berlin ZAS Papers in Linguistics 19, 2000 Investigations in Prosodie Phonology: The Role of the Foot and the Phonologieal Word Edited by T. A. Hall & Marzena Roehon Contents 'j I Prefaee III Bozena Cetnarowska (University 0/ Silesia, Sosnowiec/Katowice, Poland) On the (non-) reeursivity of the prosodie word in Polish 1 Laum 1. Downing (ZAS Berlin) Satisfying minimality in Ndebele 23 T. A. Hall (University of Leipzig) The distribution of trimoraie syllables in German and English as evidenee for the phonologieal word 41 David J. Holsinger (ZAS Berlin) Weak position eonstraints: the role of prosodie templates in eontrast distribution 91 Arsalan Kahnemuyipour (University ofToronto) The word is a phrase, phonologieally: evidenee from Persian stress 119 Renate Raffelsiefen (Free University of Berlin) Prosodie form and identity effeets in German 137 Marzena RochOl1. (ZAS BerUn) Prosodie eonstituents in the representation of eonsonantal sequenees in Polish 177 Caroline R. Wiltshire (University of Florida, Gainesville) Crossing word boundaries: eonstraints for misaligned syllabifieation 207 ZAS Papers in Linguistics 19,2000 On the (non-)reeursivity ofthe prosodie word in Polish* Bozena Cetnarowska University of Silesia, Sosnowiec/Katowice, Poland 1 The problem The present paper investigates the relationship between the morphological word and the prosodie word in Polish sequences consisting of proclitics and lexical words. -

Milton Keynes Archaeology Unit Carried Our the Most Intensive Archaeological Investigation Yet Undertaken of Part of the East Midlands Countryside

THE MJ[Ll'O N KJE '1{NJE S PROJJE C 1' R. J. ZEEPVAT Between 1971 and 1991, the Milton Keynes Archaeology Unit carried our the most intensive archaeological investigation yet undertaken of part of the East Midlands countryside. This paper summarises the arch.aeo!Ggicallandscapes that can be constructed ji·om the results of this work, and assesses the methods employed to obtain them. Introduction Milton Keynes is underlain by beds of Oxford The new city of Milton Keynes covers an area Clay, which outcrop extensively on the west of some ninety square kilometres, straddling side of the Ouzel floodplain, which forms the the narrowest part of north Buckinghamshire, east side of the city. Much of this central area is with the counties of Bedfordshire and North• covered by glacial deposits of Boulder Clay, amptonshire to the south-east and north res• whilst both glacial and alluvial deposits of pectively (Fig. 1). Part of the reasoning behind gravel are found in the Ouse and Ouzel valleys. the choice of this location can be seen in its Rocky outcrops are mainly confined to areas situation on the principal natural 'corridor' bordering the O use valley. Soils in the area are linking the south-east to the Midlands and heavy, though lighter soils are found in areas of north, a route followed by all the major forms gravel subsoil, and drainage is generally poor of surface transport, ancient and modern. even in the riv·er valleys, which were prone to flooding until recent years. Until the designation of Milton Keynes, the area was devoted almost entirely to agri• Despite its situation on a major communica• culture. -

Culturetalk Albania Video Transcripts: Let’S Have a Coffee

CultureTalk Albania Video Transcripts: http://langmedia.fivecolleges.edu Let’s Have a Coffee Southern Albanian dialect Albanian transcript: 1: Po persa i perket ngjashmerive apo ndryshimeve ne pervojen tende ne Turqi dhe Amerike? Persa i perket, bjen fjala, funeraleve, ditelindjeve, festave, vizitave – nqs veme kete pervoje ne sfond. 2: Po... 1: Ose, nuk eshte e thene qe te vihet pikerisht kjo, ky rast, por dhe ndonje rast tjeter qe ti mendon se mund te jete interesant nese perballet me pervoja, po themi, Stambolli apo Amerika. 2: Po tani te gjithe... Ekziston nje besim i tille qe e kam vene re ne shume shqiptare qe psh, ne ne Shqiperi kemi... ne jemi shume, dmth... keta kulturat e tjera si psh, turqit ose amerikanet se varet nga konteksti, jane me artificiale. Dmth ndryshimi per ne. Por nje gje qe me vjen per te qeshur, ca njerez, jo te gjithe njerez, por ca njerez ne Shqiperi dalin per xhiro, ne Shqiperi. Psh, bejne promonaden ose familjarisht ose vetem. Ketu, edhe ne Turqi, edhe ne Amerike, edhe une, edhe shume njerez dalin te shikojne. Por eshte me ndryshe. Ka me pak ceremoni se si ndodh ne Shqiperi. Ajo eshte nje ndryshim qe mund te pakten thuhet. E dyta, njerezit ne Shqiperi shkojne per kafe, dhe eshte gje e madhe. Ndersa edhe ne Turqi, edhe ne Amerike – po i ve Turqine dhe Ameriken bashke – eshte... ky simboli i te shkuarit ne kafe perdoret me pak. Ne Shqiperi per cdo gje “do pime nje kafe”. Tani dihet ajo qe nuk do pish kafe, por eshte qe.. -

1 Phrase-Level Obstruent Voicing in Polish: a Derivational OT Account

1 Phrase-level obstruent voicing in Polish: a Derivational OT account Karolina Broś 1. Introduction Polish distinguishes between two dialectal behaviours, one of which apparently involves presonorant assimilation across word boundaries. Although both Warsaw and Cracow/Poznań dialects present voice assimilation (VA, as in chlebka [xlɛ.pka] ‘bread’ dim. gen., chleb Tomka [xlɛp.tɔm.ka] ‘Tom’s bread’ vs. chleba [xlɛ.ba] ‘bread’ gen.) and final devoicing (FD, as in chleb [xlɛp] ‘bread’ nom. sg.), only Cracow/Poznań admits voicing before sonorants across word boundaries (brat Adama [brad.a.da.ma] ‘Adam's brother’, brat Magdy [brad.mag.dɨ] ‘Magda’s brother’). Traditional pre-OT accounts of this phenomenon (Gussman 1992, Rubach 1996) rely on autosegmental delinking cum spreading which requires that word-final obstruents be distinguished from word-medial ones by the prior application of FD (underspecification). However, this is incompatible with the results of the latest phonetic studies. As noted by Strycharczuk (2012), Cracow/Poznań voicing data suggest that FD is a phrase-final process: full neutralisation in voicing can only be observed prepausally. In all other cases final obstruents share the voicing specification with the following sound (bra[t] ‘brother’, bra[d.a]dama ‘Adam's brother’, bra[d.m]agdy ‘Magda’s brother’, bra[t.k]asi ‘Kasia’s brother’ and bra[d.g]osi ‘Gosia’s brother’) to some extent. Moreover, there is variability in and across speaker productions, which puts the categorical nature of Cracow/Poznań voicing into doubt. In view of these data, I argue that Cracow/Poznań Polish has no FD in the traditional sense. -

Spl 11 2016 2

Studies in Polish Linguistics vol. 11, 2016, issue 3, pp. 111–111111–131 doi: 10.4467/23005920SPL.16.005.587910.4467/23005920SPL.16.006.5880 www.ejournals.eu/SPL Paweł Rydzewski University of Warsaw A Polish Argument for the Underlying Status of [ɨ] Abstract Th is article argues against the single-phoneme approach discussed in Padgett (2001, 2003, 2010), which does not recognize the phonemic status of the vowel [ɨ]. Th e relevant data are drawn from the processes of Polish palatalization in the class of velars, while the presented analyses are couched in the theory of Lexical Phonology. It is argued that the lack of [ɨ] enforces the use of diacritics and leads to the proliferation of rules that are necessary to accommodate diacritically-specifi ed contexts of palatalization. It is also shown that the single-phoneme approach leads to the morphologization of processes that are typically phonological. On the other hand, assuming the existence of underlying [ɨ] allows for a transparent and uniform account of palatalization eff ects. Keywords palatalization, velar consonants, Polish phonology, Lexical Phonology, derivations, diacritics Streszczenie Niniejszy artykuł kwestionuje założenie jednofonemiczne według Padgetta (2001, 2003, 2010), które nie uznaje fonemicznego statusu samogłoski [ɨ]. Przedstawione dane zaczerpnięte są z ję- zyka polskiego, a ich analiza opiera się na procesach palatalizacji samogłosek tylnojęzykowych, które dla celów opisowych osadzone zostały w teorii Fonologii Leksykalnej. Artykuł ukazuje, iż obecność [ɨ] w reprezentacji głębokiej umożliwia transparentną i jednolitą analizę palatalizacji spółgłosek tylnojęzykowych, podczas gdy brak [ɨ] wymusza użycie diakrytyków oraz prowa- dzi do nadmiernego powielania reguł. Ponadto artykuł pokazuje, że założenie jednofonemiczne prowadzi do morfologizacji procesów, które są typowo fonologiczne. -

Revised May 2015 CURRICULUM VITAE GARO J. EMERZIAN, DPM

CURRICULUM VITAE GARO J. EMERZIAN, D.P.M. Illinois Bone and Joint Institute, LLC 350 S. Greenleaf Avenue 9000 Waukegan Road 900 Rand Road Suite 405 Suite 200 Suite 200 Gurnee, IL 60031 Morton Grove, IL 60053 Des Plaines, IL 60016 847-336-3335 847-375-3000 847-375-3000 Education: Northern Illinois University, B.S. Degree Dec., 1983 to 1987 Dr. William Scholl College of Podiatric Medicine 1988 to May 1992 Residency: Edgewater Medical Center/Day SurgiCenters, Inc., Chicago, IL 1992 to July 1994 Podiatric Surgery Two Year Chief Resident: July 1, 1993 – December 31, 1993 Fellowship: Illinois Bone and Joint Institute, Park Ridge, IL 1994 to July 1995 Foot and Ankle Reconstruction Board Certification and Licensure: American Board Podiatric Surgery, Reconstructive Rear Foot and Ankle Surgery 2001 Recertified 2011 American Board of Podiatric Surgery, Foot Surgery 1999 Recertified 2009 American Board of Podiatric Orthopaedics and Primary Podiatric Medicine, 1996 Orthopaedic Division Recertified 2007 Illinois Podiatric Medicine License, Active 1992 Wisconsin Podiatric Medicine License, Inactive Nevada Podiatric Medicine License, Active Other Certifications: DePuy Agility Ankle Certification April 2004 Professional Appointments: Rush Northshore Associate Staff 2001 ENH Network, Evanston, Glenbrook and Highland Park, IL Associate Staff 1996- present Vista Medical Center, Waukegan, IL Provisional Staff 1999 Chief of Podiatry Section 2000 Condell Medical Center Provisional Staff 2000 Advocate Lutheran General Hospital Associate Staff 2007 Northwestern -

Chapter X Positional Factors in Lenition and Fortition

Chapter X Positional factors in Lenition and Fortition 1. Introduction This chapter sets out to identify the bearing that the linear position of a segment may have on its lenition or fortition.1 We take for granted the defi- nition of lenition that has been provided in chapter XXX (Szigetvári): Put- ting aside stress-related lenition (see chapter XXX de Lacy-Bye), the refer- ence to the position of a segment in the linear string is another way of identifying syllabic causality. Something is a lenition iff the effect ob- served is triggered by the specific syllabic status of the segment at hand. The melodic environment thus is irrelevant, and no melodic prime is trans- mitted between segments. Lenition thereby contrasts with the other family of processes that is found in phonology, i.e. adjacency effects. Adjacency may be defined physically (e.g. palatalisation of a consonant by a following vowel) or in more abstract terms (e.g. vowel harmony): in any event, as- similations will transmit a melodic prime from one segment to another, and only a melodically defined subset of items will qualify as a trigger. Posi- tional factors, on the other hand, are unheard of in assimilatory processes: there is no palatalisation that demands, say, "palatalise velars before front vowels, but only in word-initial position". Based on an empirical record that we have tried to make as cross- linguistically relevant as possible, the purpose of this chapter is to establish appropriate empirical generalisations. These are then designed to serve as the input to theories of lenition: here are the challenges, this is what any theory needs to be able to explain. -

1 Symbols (2286)

1 Symbols (2286) USV Symbol Macro(s) Description 0009 \textHT <control> 000A \textLF <control> 000D \textCR <control> 0022 ” \textquotedbl QUOTATION MARK 0023 # \texthash NUMBER SIGN \textnumbersign 0024 $ \textdollar DOLLAR SIGN 0025 % \textpercent PERCENT SIGN 0026 & \textampersand AMPERSAND 0027 ’ \textquotesingle APOSTROPHE 0028 ( \textparenleft LEFT PARENTHESIS 0029 ) \textparenright RIGHT PARENTHESIS 002A * \textasteriskcentered ASTERISK 002B + \textMVPlus PLUS SIGN 002C , \textMVComma COMMA 002D - \textMVMinus HYPHEN-MINUS 002E . \textMVPeriod FULL STOP 002F / \textMVDivision SOLIDUS 0030 0 \textMVZero DIGIT ZERO 0031 1 \textMVOne DIGIT ONE 0032 2 \textMVTwo DIGIT TWO 0033 3 \textMVThree DIGIT THREE 0034 4 \textMVFour DIGIT FOUR 0035 5 \textMVFive DIGIT FIVE 0036 6 \textMVSix DIGIT SIX 0037 7 \textMVSeven DIGIT SEVEN 0038 8 \textMVEight DIGIT EIGHT 0039 9 \textMVNine DIGIT NINE 003C < \textless LESS-THAN SIGN 003D = \textequals EQUALS SIGN 003E > \textgreater GREATER-THAN SIGN 0040 @ \textMVAt COMMERCIAL AT 005C \ \textbackslash REVERSE SOLIDUS 005E ^ \textasciicircum CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT 005F _ \textunderscore LOW LINE 0060 ‘ \textasciigrave GRAVE ACCENT 0067 g \textg LATIN SMALL LETTER G 007B { \textbraceleft LEFT CURLY BRACKET 007C | \textbar VERTICAL LINE 007D } \textbraceright RIGHT CURLY BRACKET 007E ~ \textasciitilde TILDE 00A0 \nobreakspace NO-BREAK SPACE 00A1 ¡ \textexclamdown INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK 00A2 ¢ \textcent CENT SIGN 00A3 £ \textsterling POUND SIGN 00A4 ¤ \textcurrency CURRENCY SIGN 00A5 ¥ \textyen YEN SIGN 00A6 -

KJE Investments Disposition and Development Agreement

DISPOSITION AND DEVELOPMENT AGREEMENT by and among THE CITY OF DALY CITY and KJE INVESTMENTS LLC a California limited liability company The Real Properties Known as San Mateo County Assessor’s Parcels Number 002-352-200, 002-352-210, 002-352-220, 002-352-230, 002-352-240, 002-342-160, and a portion of 002-352-250; and a portion of 002-342-250 _______________, 2020 1 THIS DISPOSITION AND DEVELOPMENT AGREEMENT (this “Agreement”) is entered into effective as of ____________, 2020 (“Effective Date”) by and among the City of Daly City, a municipal corporation (“City”) and KJE Investments LLC, a California limited liability company (“KJE” or “Developer”). City and KJE are collectively referred to herein as the “Parties.” RECITALS A. The City is the owner of the real property located at the intersection of Westlake Avenue and Junipero Serra Boulevard in Daly City, California, known as San Mateo County Assessor’s Parcel Nos. (“APN”) 002-352-160, 002-352-290, 002-352-310, 002-362-330, and more particularly described in Exhibit A-1 and depicted in Exhibit A-3 attached hereto (collectively, “North-of-Westlake Parcels”); and APNs 002-352-200, 002-352-210, 002-352- 220, 002-352-230, 002-352-240, 002-342-160, 002-252-250, and 002-342-250 which are more particularly described in Exhibit A-4, and a portion of which is depicted in Exhibit A-5 (collectively, “South-of-Westlake Parcels”) (collectively, the North-of-Westlake Parcels and the South-of-Westlake Parcels are referred to as the “Property”). The Property was conveyed to the City by the Successor Agency to the Daly City Redevelopment Agency pursuant to a Long- Range Property Management Plan approved by the California Department of Finance in accordance with Health and Safety Code Section 34191.5. -

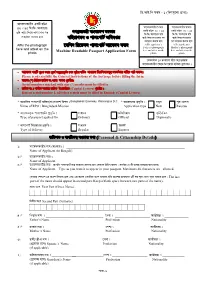

MRP Application Form

¢X.BC.¢f glj - 1 (¢he¡j¨−mÉ fÊ¡fÉ) A¡−hceL¡l£l HL¢V l¢Pe 55 ^ 45 ¢jx¢jx A¡L¡−ll A¡−hceL¡l£l ¢fa¡l A¡−hceL¡l£l j¡a¡l NZfÊS¡a¿»£ h¡wm¡−cn plL¡l HL¢V l¢Pe 30 ^ 25 HL¢V l¢Pe 30 ^ 25 R¢h A¡W¡ ¢c−u m¡N¡−e¡l fl ¢jx¢jx A¡L¡−ll R¢h ¢jx¢jx A¡L¡−ll R¢h paÉ¡ue Ll−a q−h h¢ql¡Nje J f¡p−f¡VÑ A¢dcçl A¡W¡ ¢c−u m¡N¡−e¡l fl A¡W¡ ¢c−u m¡N¡−e¡l paÉ¡ue Ll−a q−h fl paÉ¡ue Ll−a q−h Affix the photograph Affix applicant’s Affix applicant’s −j¢ne ¢l−Xhm f¡p−f¡VÑ A¡−hce glj Father’s photograph Mother’s photograph here and attest on the Machine Readable Passport Application Form here and attest on the here and attest on the photo photo photo −Lhmj¡œ 15 hvp−ll e£−Q AfË¡çhuú A¡−hceL¡l£l −r−œ Ef−l¡š² R¢hàu fË−u¡Se z • A¡−hce fœ¢V f¨lZ Ll¡l f¨−hÑ Ae¤NÊqf§hÑL −no fªù¡u h¢ZÑa p¡d¡le ¢e−cÑne¡pj§q paLÑa¡l p¢qa f¡W Ll²ez Please read carefully the General Instructions at the last page before filling the form. • a¡lL¡ (*) ¢Q¢q²a œ²¢jL ew …−m¡ AhnÉ f¨lZ£uz Serial numbers marked with star (*) marks must be filled in.