Nathan Moore Final-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandhi and India: the Dream and Reality of India

GANDHI AND INDIA: THE DREAM AND REALITY OF INDIA Anthony Thomas Schultz Department of History History 489 Capstone Paper Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire with the consent of the author. Contents ABSTRACT 3 INTRODUCTION 4 The Rise of Mahatma Gandhi 7 Satyagraha (Non-Violent Resistance) 9 The hopes and dreams for India 13 India after Gandhi 20 The people of India 30 CONCLUSION 36 WORKS CITED 38 2 Abstract India has been one of the fastest growing nations in the world in the past couple of decades. India, like the United States, was once under British rule. M.K. Gandhi and many others tried and were successful in pushing British rule out of their country and forging their own nation. Once India was freed from British rule, many of India’s prominent figures had views and dreams for the course the country would take, especially Gandhi. Today, India is a thriving country, with a population of over a billion, and is a major player in world political affairs. However, some wonder if Gandhi’s dream for India came true or if it is still a work in progress. This paper attempts to examine the ideal that Gandhi had in mind during the final years of his life and compare it to today’s modern day India. By looking at Gandhi’s own original work from his autobiography, his other writings and some sources from individuals that he worked with, it will give a picture of what Gandhi might have wanted for India. -

The Political and Social Thought of Lewis Corey

70-13,988 BROWN, David Evan, 19 33- THE POLITICAL AND SOCIAL THOUGHT OF LEWIS COREY. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1969 Political Science, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE POLITICAL AND SOCIAL THOUGHT OF LEWIS COREY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David Evan Brown, B.A, ******* The Ohio State University 1969 Approved by Adviser Department of Political Science PREFACE On December 2 3 , 1952, Lewis Corey was served with a warrant for his arrest by officers of the U, S, Department of Justice. He was, so the warrant read, subject to deportation under the "Act of October 16 , 1 9 1 8 , as amended, for the reason that you have been prior to entry a member of the following class: an alien who is a member of an organi zation which was the direct predecessor of the Communist Party of the United States, to wit The Communist Party of America."^ A hearing, originally arranged for April 7» 1953» but delayed until July 27 because of Corey's poor health, was held; but a ruling was not handed down at that time. The Special Inquiry Officer in charge of the case adjourned the hearing pending the receipt of a full report of Corey's activities o during the previous ten years. [The testimony during the hearing had focused primarily on Corey's early writings and political activities.] The hearing was not reconvened, and the question of the defendant's guilt or innocence, as charged, was never formally settled. -

American Opinion of the Soviet/Vatican Struggle 1917-1933

University of Central Florida STARS Retrospective Theses and Dissertations 1988 American opinion of the soviet/vatican struggle 1917-1933 Jeffrey P. Begeal University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/rtd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Begeal, Jeffrey P., "American opinion of the soviet/vatican struggle 1917-1933" (1988). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 4260. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/rtd/4260 AMERICA N CPJ}:-TON· Of· THE SOVIET/VATI CAN STRUGGLE 1917-1933 BY JEFFREY PAUL BEGEAL B.A., Mercer University, 1982 THESIS .Submi.·ct~!d. in partial fulfillment of the requirements f o r the Master of Arts dEgree in History in the Graduate Studies Program of the College of Arts and Sciences University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 1988 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface -·················· .,.,. • 1o1 ••··· .. ··•• »••···.,······ iii Chapter I. THE REVOLUTION OF MARCH 1917 ................ 1 II. THE REVOLUTION OF NOVEMBER 1917 .............. 12 III. THE GENOA CONFERENCE, 1922 .................. 26 IV. THE CATHOLIC CLERGY TRIAL, 1923 .. .......... 41 v. THE FAMINE RELIEF MISSION OF 1921-1924 ...... 56 VI. THE PRAYER CRUSADE OF 1930 .................. 65 VII. THE RECOGNITION DEBATE, 1933 ................ 78 Conclusion . 91 NOTES . 96 APPENDIX I WALSH TO CREEDEN, 27 SEPTEMBER 1923 . ..... 105 APPENDIX II WORKS CONSULTED .......................... 108 WORKS CITED 114 PREFACE The first sixteen years of the history of Soviet/ Vatican relaticns represented one of the most profound ideological and political struggles of the twentieth century. -

LENIN the DICTATOR an Intimate Portrait

LENIN THE DICTATOR An Intimate Portrait VICTOR SEBESTYEN LLeninenin TThehe DDictatorictator - PP4.indd4.indd v 117/01/20177/01/2017 112:372:37 First published in Great Britain in 2017 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 © Victor Sebestyen 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher. The right of Victor Sebestyen to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. HB ISBN 978 1 47460044 6 TPB 978 1 47460045 3 Typeset by Input Data Services Ltd, Bridgwater, Somerset Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Weidenfeld & Nicolson The Orion Publishing Group Ltd Carmelite House 50 Victoria Embankment London EC4Y 0DZ An Hachette UK Company www.orionbooks.co.uk LLeninenin TThehe DDictatorictator - PP4.indd4.indd vvii 117/01/20177/01/2017 112:372:37 In Memory of C. H. LLeninenin TThehe DDictatorictator - PP4.indd4.indd vviiii 117/01/20177/01/2017 112:372:37 MAPS LLeninenin TThehe DDictatorictator - PP4.indd4.indd xxii 117/01/20177/01/2017 112:372:37 NORTH NORWAY London SEA (independent 1905) F SWEDEN O Y H C D U N D A D L Stockholm AN IN GR F Tammerfors FRANCE GERMANGERMAN EMPIRE Helsingfors EMPIRE BALTIC Berlin SEA Potsdam Riga -

Netaji and Gandhi : a Different Look

August - 2014 Odisha Review Netaji and Gandhi : A Different Look Dr. Sridhar Charan Sahoo Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and Subhas Chandra Bose had the same objective of liberating the country from the yoke of British imperialism. Until the political clash at Tripuri they worked more or less together under the common platform of the Indian National Congress for about two decades. After his escape from the country during the Second World War, Bose gave up the Gandhian method of Satyagraha and non-violent non-cooperation. He secured the help and assistance of the Axis powers, organized an armed struggle from outside the country and tried to overthrow British imperialism from the Indian soil by force of arms. This mutual divergence in the means and method of struggle has led many scholars to delineate Subhas – Gandhi relationship in more or less dichotomous and incompatible terms. It has been said that in their pursuit of the truth of the matter is that, in a way, there seems to objective of freedom “each stuck to his ideas, have been some meaningful and fruitful interaction refused to make any compromise to between them inspite of all their divergence. accommodate the views of the other because their stances were almost always diametrically In our paper, we have tried to search opposed.1 Further, it has been said “Bose was a bonds of unity between Netaji and Gandhi even soldier, Gandhi a statesman, Bose believed in the though both of them differed as regards their sword, Gandhi in non-violence; Bose believed in means and method of struggle more particularly ends, Gandhi in the means”2. -

Howard Fast, 1956 and American Communism PHILLIP DEERY* Victoria University, Melbourne

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Victoria University Eprints Repository 1 Finding his Kronstadt: Howard Fast, 1956 and American Communism PHILLIP DEERY* Victoria University, Melbourne The scholarship on the impact on communists of Khrushchev’s “secret speech” to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956 is limited. Generally it is located within broader studies of organisational upheavals and ideological debates at the leadership level of communist parties. Rarely has there been analysis of the reverberations at the individual level. Consistent with Barrett’s pioneering approach, this paper seeks to incorporate the personal into the political, and inject a subjective dimension into the familiar top-down narrative of American communism. It will do this by focusing on the motivations, reactions and consequences of the defection of one Party member, the writer Howard Fast. It will thereby illuminate the story of personal anguish experienced by thousands in the wake of Khrushchev’s revelations about Stalin. The Defection On 1 February 1957, the front-page of the New York Times (NYT) carried a story that reverberated across the nation and, thereafter, the world. It began: “Howard Fast said yesterday that he had dissociated himself from the American Communist party and no longer considered himself a communist”.1 The NYT article was carried by scores of local, state and national newspapers across the country. Why was this story such a scoop and why was it given -

George F. Kennan Oral History Interview – JFK#1, 03/23/1965 Administrative Information

George F. Kennan Oral History Interview – JFK#1, 03/23/1965 Administrative Information Creator: George F. Kennan Interviewer: Louis Fischer Date of Interview: March 23, 1965 Place of Interview: Princeton, New Jersey Length: 141 pages Biographical Note Kennan, United States Ambassador to Yugoslavia (1961 - 1963), discusses his position as United States Ambassador to Yugoslavia and his working relationship with John F. Kennedy, among other issues. Access Open Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed March 4, 1966, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. Direct your questions concerning copyright to the reference staff. -

100 Questions to the Communists

"7 7'"' - ...-.... 100 tl~- fo JluL By STEPHEN NAFT RAND SCHOOL PRESS Price: 10 ·cents cu: - :w Copyright, 1939 RAND SCHOOL PRESS 7 East 15th Street, New York City -~·178 100 QUESTIONS TO THE COMMUNISTS By Stephen Naft HE following questions, addressed to sympathizers, T fellow-travelers and members of the Communist Pa.rty, are put with the sincere intention not to antago m-ie.- but rather to evoke answers in their own thoughts on the basis of their own independent sincere reasoning. These questions are not addressed to those who will ~satisfied in their own minds with evasive or polemical jQ-,tincations of every act of "my party, right or wrong." The blind thoughtless acceptance and parroting of offi<!ial, inaehine-made arguments passed on to the rank and file by the party authotities or mendacious denials of facts unanimously reported by hundreds of correspondents, observers and workers who went to the Soviet Union with enthusiasm or sympathy and stayed there for any length of time, is in direct contradiction to the spirit and ideal of all sincere movements for the betterment of mankind. Lying and fraudulent arguments can only help fraudu )e.llt ~uses. These are the methods of fascism. Therefore we hope that every honest sympathizer and supporter of Communist and Socialist aspirations, who consequently must cherish the ideals of personal and eco nomic security, of freedom, of justice, social equality and br&therly solidarity will not only understand and appre ei:ate 611!' motives but will welcome these questions as an QPJ)Ort\lnity !or self-criticism and self-evaluation of his At~itude towards the principles dear to him. -

INDIGO -LOUIS FISCHER About the Author: Louis Fischer (1896-1970

INDIGO -LOUIS FISCHER About the Author: Louis Fischer (1896-1970) was born in Philadelphia in 1896. He served as a volunteer in the British Army between 1918-1920. Fischer made a career as a journalist and wrote for The New York Times, The Saturday Review and for European and Asian publications. He was also a member of the faculty of Princeton University. Introduction: In this story, Louis describes Gandhi’s struggle for the poor peasants of Champaran who were the sharecroppers with the British planters. They led a miserable life and were forced to grow indigo according to an agreement. They suffered a great injustice due to the landlord system in Bihar. Gandhi waged a war for about a year against their atrocities and brought justice to the poor peasants. Characters: ▪ Raj Kumar Shukla: A sharecropper ▪ Charles Freer Andrews: A follower of Gandhi ▪ Kasturba: Wife of Gandhi ▪ Devdas: youngest son of Gandhi Gist of the lesson: • Raj Kumar Shukla- A poor sharecropper from Champaran wishing to meet Gandhiji. • Raj Kumar Shukla – illiterate but resolute, hence followed Gandhiji to Lucknow, Cawnpore, Ahmedabad, Calcutta, Patna, Muzzafarpur and then Champaran. • Servants at Rajendra Prasad’s residence thought Gandhiji to be an untouchable. • Gandhiji considered as an untouchable because of simple living style and wearing, due to the company of Raj Kumar Shukla. • Decided to go to Muzzafarpur first to get detailed information about Champaran sharecropper. • Sent telegram to J B Kriplani & stayed in Prof Malkani’s home –a government servant. • Indians afraid of showing sympathy to the supporters of home rule. • The news of Gandhiji’s arrival spread –sharecroppers gathered in large number to meet their champion. -

An Alaskan's Journey, by Victor Fischer with Charles Wohlforth

REVIEWS • 369 that the absence of a trend or reduced increase in tempera- TO RUSSIA WITH LOVE: AN ALASKAN’S JOURNEY. ture of warm permafrost is likely due to the absorption of By VICTOR FISCHER with CHARLES WOHLFORTH. Fair- latent heat required for phase change (Riseborough, 1990) banks: University of Alaska Press, 2012. ISBN 978-1- and is therefore an expected characteristic of warming per- 60223-139-9. xv + 405 p., b&w and colour illus., chapter mafrost as ground temperatures approach 0˚C. The expla- notes, index. Hardbound. US$27.95. nation for this phenomenon is only provided much later (p. 139) in a chapter by Chris Burn on “Permafrost Distri- Firsthand encounters with momentous challenges mark the bution and Stability.” author’s life, from the early 20th into the 21st century. Son A particular theme in the book which I enjoyed was the of two authors, American Louis Fischer and Latvian-born emphasis on spatial and temporal variation of physical pro- Markoosha, Victor (“Vic” to his friends and colleagues) cesses and the role of past processes, specifically glacia- reached adolescence as “Vitya” in Moscow, USSR. Vic’s tion, on shaping the current landscape and its vulnerability fascination with the North and Alaska began there, at the to change. This context is set early in the text by French Fridtjof Nansen School, where élite students learned to and Slaymaker, who remind readers that Canada’s cold admire pioneering feats, exemplified by the Norwegian regions are characterized by diversity and that many land- polar pioneer for whom the school was named. -

Roundtable-XVI-10.Pdf

2014 H-Diplo Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane Labrosse H-Diplo Roundtable Review Roundtable and Web Production Editor: George Fujii h-diplo.org/roundtables Volume XVI, No. 10 (2014) 17 November 2014 Introduction by William Keylor Michael Jabara Carley. Silent Conflict. A Hidden History of Early Soviet-Western Relations. Lanham Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014. ISBN: 978-1-4422-2585-5 (hardback, $45.00). URL: http://www.tiny.cc/Roundtable-XVI-10 or http://h-diplo.org/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-XVI-10.pdf Contents Introduction by William Keylor, Boston University .................................................................. 2 Review by Alexey Filitov, Institute of Universal History, Russian Academy of Sciences .......... 7 Review by Jonathan Haslam, Cambridge University .............................................................. 12 Review by Richard Overy, University of Exeter ...................................................................... 17 Author’s Response by Michael Jabara Carley, Université de Montréal ................................. 21 © 2014 H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews, Vol. XVI, No. 10 (2014) Introduction by William Keylor, Boston University ast summer, as President Vladimir Putin annexed the Crimea (with its Russian- speaking majority) and began to apply pressure on Ukraine (with its Russian- L speaking minority), I was completing my reading -

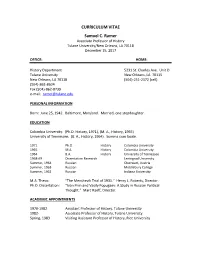

CURRICULUM VITAE Samuel C. Ramer

CURRICULUM VITAE Samuel C. Ramer Associate Professor of History Tulane University/New Orleans, LA 70118 December 15, 2017 OFFICE: HOME: History Department 5231 St. Charles Ave. Unit D Tulane University New Orleans, LA 70115 New Orleans, LA 70118 (504)-251-2372 (cell) (504)-862-8604 Fax (504)-862-8739 e-mail: [email protected] PERSONAL INFORMATION Born: June 25, 1942. Baltimore, Maryland. Married, one stepdaughter. EDUCATION Columbia University: (Ph.D. History, 1971), (M. A., History, 1965) University of Tennessee: (B. A., History, 1964). Summa cum laude. 1971 Ph.D. History Columbia University 1965 M.A. History Columbia University 1964 B.A. History University of Tennessee 1968-69 Dissertation Research Leningrad University Summer, 1964 Russian Oberwart, Austria Summer, 1963 Russian Middlebury College Summer, 1962 Russian Indiana University M.A. Thesis: “The Menshevik Trial of 1931.” Henry L. Roberts, Director. Ph.D. Dissertation: “Ivan Pnin and Vasily Popugaev: A Study in Russian Political Thought.” Marc Raeff, Director. ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 1970-1982 Assistant Professor of History, Tulane University 1982- Associate Professor of History, Tulane University Spring, 1983 Visiting Assistant Professor of History, Rice University Samuel C. Ramer: Resumé 2 GRANTS AND FELLOWSHIPS July, 2005 Director, Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities Teacher Institute for Advanced Study “Poetry and Power: The Genius of Alexander Pushkin” July 5-28, 2005 2004 Eva-Lou Joffrion Edwards grant from Newcomb College to develop course entitled “The History of the Jews in Russia, 1772- 2000.” 1998-1999 International Research and Exchanges Board Grant for The Guidebook Development Project for the National Pushkin Museum Library in St. Petersburg, Russia 1994-1998 Continuation of DOE grant establishing collaborative research with the Institute of Radioecological Problems in Minsk, Belarus.