Work W = ΔE = Fd W =

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

Classical Mechanics

Classical Mechanics Hyoungsoon Choi Spring, 2014 Contents 1 Introduction4 1.1 Kinematics and Kinetics . .5 1.2 Kinematics: Watching Wallace and Gromit ............6 1.3 Inertia and Inertial Frame . .8 2 Newton's Laws of Motion 10 2.1 The First Law: The Law of Inertia . 10 2.2 The Second Law: The Equation of Motion . 11 2.3 The Third Law: The Law of Action and Reaction . 12 3 Laws of Conservation 14 3.1 Conservation of Momentum . 14 3.2 Conservation of Angular Momentum . 15 3.3 Conservation of Energy . 17 3.3.1 Kinetic energy . 17 3.3.2 Potential energy . 18 3.3.3 Mechanical energy conservation . 19 4 Solving Equation of Motions 20 4.1 Force-Free Motion . 21 4.2 Constant Force Motion . 22 4.2.1 Constant force motion in one dimension . 22 4.2.2 Constant force motion in two dimensions . 23 4.3 Varying Force Motion . 25 4.3.1 Drag force . 25 4.3.2 Harmonic oscillator . 29 5 Lagrangian Mechanics 30 5.1 Configuration Space . 30 5.2 Lagrangian Equations of Motion . 32 5.3 Generalized Coordinates . 34 5.4 Lagrangian Mechanics . 36 5.5 D'Alembert's Principle . 37 5.6 Conjugate Variables . 39 1 CONTENTS 2 6 Hamiltonian Mechanics 40 6.1 Legendre Transformation: From Lagrangian to Hamiltonian . 40 6.2 Hamilton's Equations . 41 6.3 Configuration Space and Phase Space . 43 6.4 Hamiltonian and Energy . 45 7 Central Force Motion 47 7.1 Conservation Laws in Central Force Field . 47 7.2 The Path Equation . -

THE EARTH's GRAVITY OUTLINE the Earth's Gravitational Field

GEOPHYSICS (08/430/0012) THE EARTH'S GRAVITY OUTLINE The Earth's gravitational field 2 Newton's law of gravitation: Fgrav = GMm=r ; Gravitational field = gravitational acceleration g; gravitational potential, equipotential surfaces. g for a non–rotating spherically symmetric Earth; Effects of rotation and ellipticity – variation with latitude, the reference ellipsoid and International Gravity Formula; Effects of elevation and topography, intervening rock, density inhomogeneities, tides. The geoid: equipotential mean–sea–level surface on which g = IGF value. Gravity surveys Measurement: gravity units, gravimeters, survey procedures; the geoid; satellite altimetry. Gravity corrections – latitude, elevation, Bouguer, terrain, drift; Interpretation of gravity anomalies: regional–residual separation; regional variations and deep (crust, mantle) structure; local variations and shallow density anomalies; Examples of Bouguer gravity anomalies. Isostasy Mechanism: level of compensation; Pratt and Airy models; mountain roots; Isostasy and free–air gravity, examples of isostatic balance and isostatic anomalies. Background reading: Fowler §5.1–5.6; Lowrie §2.2–2.6; Kearey & Vine §2.11. GEOPHYSICS (08/430/0012) THE EARTH'S GRAVITY FIELD Newton's law of gravitation is: ¯ GMm F = r2 11 2 2 1 3 2 where the Gravitational Constant G = 6:673 10− Nm kg− (kg− m s− ). ¢ The field strength of the Earth's gravitational field is defined as the gravitational force acting on unit mass. From Newton's third¯ law of mechanics, F = ma, it follows that gravitational force per unit mass = gravitational acceleration g. g is approximately 9:8m/s2 at the surface of the Earth. A related concept is gravitational potential: the gravitational potential V at a point P is the work done against gravity in ¯ P bringing unit mass from infinity to P. -

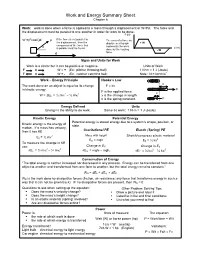

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6 Work: work is done when a force is applied to a mass through a displacement or W=Fd. The force and the displacement must be parallel to one another in order for work to be done. F (N) W =(Fcosθ)d F If the force is not parallel to The area of a force vs. the displacement, then the displacement graph + W component of the force that represents the work θ d (m) is parallel must be found. done by the varying - W d force. Signs and Units for Work Work is a scalar but it can be positive or negative. Units of Work F d W = + (Ex: pitcher throwing ball) 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) F d W = - (Ex. catcher catching ball) Note: N = kg m/s2 • Work – Energy Principle Hooke’s Law x The work done on an object is equal to its change F = kx in kinetic energy. F F is the applied force. 2 2 x W = ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi x is the change in length. k is the spring constant. F Energy Defined Units Energy is the ability to do work. Same as work: 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) Kinetic Energy Potential Energy Potential energy is stored energy due to a system’s shape, position, or Kinetic energy is the energy of state. motion. If a mass has velocity, Gravitational PE Elastic (Spring) PE then it has KE 2 Mass with height Stretch/compress elastic material Ek = ½ mv 2 EG = mgh EE = ½ kx To measure the change in KE Change in E use: G Change in ES 2 2 2 2 ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi ΔEG = mghf – mghi ΔEE = ½ kxf – ½ kxi Conservation of Energy “The total energy is neither increased nor decreased in any process. -

Force and Motion

Force and motion Science teaching unit Disclaimer The Department for Children, Schools and Families wishes to make it clear that the Department and its agents accept no responsibility for the actual content of any materials suggested as information sources in this publication, whether these are in the form of printed publications or on a website. In these materials icons, logos, software products and websites are used for contextual and practical reasons. Their use should not be interpreted as an endorsement of particular companies or their products. The websites referred to in these materials existed at the time of going to print. Please check all website references carefully to see if they have changed and substitute other references where appropriate. Force and motion First published in 2008 Ref: 00094-2008DVD-EN The National Strategies | Secondary 1 Force and motion Contents Force and motion 3 Lift-off activity: Remember forces? 7 Lesson 1: Identifying and representing forces 12 Lesson 2: Representing motion – distance/time/speed 18 Lesson 3: Representing motion – speed and acceleration 27 Lesson 4: Linking force and motion 49 Lesson 5: Investigating motion 66 © Crown copyright 2008 00094-2008DVD-EN The National Strategies | Secondary 3 Force and motion Force and motion Background This teaching sequence bridges from Key Stage 3 to Key Stage 4. It links to the Secondary National Strategy Framework for science yearly learning objectives and provides coverage of parts of the QCA Programme of Study for science. The overall aim of the sequence is for pupils to review and refine their ideas about forces from Key Stage 3, to develop a meaningful understanding of ways of representing motion (graphically and through calculation) and to make the links between different kinds of motion and forces acting. -

Kinetic Energy and Work

Kinetic Energy and Work 8.01 W06D1 Today’s Readings: Chapter 13 The Concept of Energy and Conservation of Energy, Sections 13.1-13.8 Announcements Problem Set 4 due Week 6 Tuesday at 9 pm in box outside 26-152 Math Review Week 6 Tuesday at 9 pm in 26-152 Kinetic Energy • Scalar quantity (reference frame dependent) 1 K = mv2 ≥ 0 2 • SI unit is joule: 1J ≡1kg ⋅m2/s2 • Change in kinetic energy: 1 2 1 2 1 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 ΔK = mv f − mv0 = m(vx, f + vy, f + vz, f ) − m(vx,0 + vy,0 + vz,0 ) 2 2 2 2 Momentum and Kinetic Energy: Single Particle Kinetic energy and momentum for a single particle are related by 2 1 2 p K = mv = 2 2m Concept Question: Pushing Carts Consider two carts, of masses m and 2m, at rest on an air track. If you push one cart for 3 seconds and then the other for the same length of time, exerting equal force on each, the kinetic energy of the light cart is 1) larger than 2) equal to 3) smaller than the kinetic energy of the heavy car. Work Done by a Constant Force for One Dimensional Motion Definition: The work W done by a constant force with an x-component, Fx, in displacing an object by Δx is equal to the x- component of the force times the displacement: W = F Δx x Concept Q.: Pushing Against a Wall The work done by the contact force of the wall on the person as the person moves away from the wall is 1. -

Feeling Joules and Watts

FEELING JOULES AND WATTS OVERVIEW & PURPOSE Power was originally measured in horsepower – literally the number of horses it took to do a particular amount of work. James Watt developed this term in the 18th century to compare the output of steam engines to the power of draft horses. This allowed people who used horses for work on a regular basis to have an intuitive understanding of power. 1 horsepower is about 746 watts. In this lab, you’ll learn about energy, work and power – including your own capacity to do work. Energy is the ability to do work. Without energy, nothing would grow, move, or change. Work is using a force to move something over some distance. work = force x distance Energy and work are measured in joules. One joule equals the work done (or energy used) when a force of one newton moves an object one meter. One newton equals the force required to accelerate one kilogram one meter per second squared. How much energy would it take to lift a can of soda (weighing 4 newtons) up two meters? work = force x distance = 4N x 2m = 8 joules Whether you lift the can of soda quickly or slowly, you are doing 8 joules of work (using 8 joules of energy). It’s often helpful, though, to measure how quickly we are doing work (or using energy). Power is the amount of work (or energy used) in a given amount of time. http://www.rdcep.org/demo-collection page 1 work power = time Power is measured in watts. One watt equals one joule per second. -

Newtonian Mechanics Is Most Straightforward in Its Formulation and Is Based on Newton’S Second Law

CLASSICAL MECHANICS D. A. Garanin September 30, 2015 1 Introduction Mechanics is part of physics studying motion of material bodies or conditions of their equilibrium. The latter is the subject of statics that is important in engineering. General properties of motion of bodies regardless of the source of motion (in particular, the role of constraints) belong to kinematics. Finally, motion caused by forces or interactions is the subject of dynamics, the biggest and most important part of mechanics. Concerning systems studied, mechanics can be divided into mechanics of material points, mechanics of rigid bodies, mechanics of elastic bodies, and mechanics of fluids: hydro- and aerodynamics. At the core of each of these areas of mechanics is the equation of motion, Newton's second law. Mechanics of material points is described by ordinary differential equations (ODE). One can distinguish between mechanics of one or few bodies and mechanics of many-body systems. Mechanics of rigid bodies is also described by ordinary differential equations, including positions and velocities of their centers and the angles defining their orientation. Mechanics of elastic bodies and fluids (that is, mechanics of continuum) is more compli- cated and described by partial differential equation. In many cases mechanics of continuum is coupled to thermodynamics, especially in aerodynamics. The subject of this course are systems described by ODE, including particles and rigid bodies. There are two limitations on classical mechanics. First, speeds of the objects should be much smaller than the speed of light, v c, otherwise it becomes relativistic mechanics. Second, the bodies should have a sufficiently large mass and/or kinetic energy. -

Physical Science Forces and Motion Vocabulary

Physical Science -Forces and Motion Vocabulary 1. scientific method - The way we learn and study the world around us through a process of steps. ( Six Giant Hippos Eat Red & Orange Candy) 2. position – the exact location of an object. 3. direction – the line or course along which something moves. 4. speed – measures how fast an object is moving in a given amount of time. 5. motion – the change in position of an object. 6. constant – remaining steady and unchanged (stays the same.) 7. force – push or pull 8. interaction – the action or influence of people, groups or things on one another. 9. exert – to put forth as strength (exert a force) 10. friction - a force that opposes (goes against) motion. Friction is created when two surfaces rub together. Effects of friction: slowing down or stopping an object, producing heat, or wearing away an object. 11. Newton’s 1 st Law of Motion : an object at rest will stay at rest and an object in motion will stay in motion until a force acts upon it. 12. inertia – the tendency for an object to keep doing what it is doing (resting or moving) 13. mass – the amount of matter (“stuff”) - in an object. 14. weight - the amount of force (pull) that gravity has on an object's mass. Your weight depends on the gravitational pull of your location. 15. gravity – a force that attracts (pulls) all objects to the center of the Earth 16. acceleration – the changes in an object’s motion. This can be speeding up, slowing down or changing direction. -

Maximum Frictional Dissipation and the Information Entropy of Windspeeds

J. Non-Equilib. Thermodyn. 2002 Vol. 27 pp. 229±238 Á Á Maximum Frictional Dissipation and the Information Entropy of Windspeeds Ralph D. Lorenz Lunar and Planetary Lab, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA Communicated by A. Bejan, Durham, NC, USA Registration Number 926 Abstract A link is developed between the work that thermally-driven winds are capable of performing and the entropy of the windspeed history: this information entropy is minimized when the minimum work required to transport the heat by wind is dissipated. When the system is less constrained, the information entropy of the windspeed record increases as the windspeed ¯uctuates to dissipate its available work. Fluctuating windspeeds are a means for the system to adjust to a peak in entropy production. 1. Introduction It has been long-known that solar heating is the driver of winds [1]. Winds represent the thermodynamic conversion of heat into work: this work is expended in accelerat- ing airmasses, with that kinetic energy ultimately dissipated by turbulent drag. Part of the challenge of the weather forecaster is to predict the speed and direction of wind. In this paper, I explore how the complexity of wind records (and more generally, of velocity descriptions of thermally-driven ¯ow) relates to the available work and the frictional or viscous dissipation. 2. Zonal Energy Balance Two linked heat ¯uxes drive the Earth's weather ± the vertical transport of heat upwards, and the transport of heat from low to high latitudes. In the present paper only horizontal transport is considered, although the concepts may be extended by analogy into the vertical dimension. -

Work-Energy for a System of Particles and Its Relation to Conservation Of

Conservation of Energy, the Work-Energy Principle, and the Mechanical Energy Balance In your study of engineering and physics, you will run across a number of engineering concepts related to energy. Three of the most common are Conservation of Energy, the Work-Energy Principle, and the Mechanical Engineering Balance. The Conservation of Energy is treated in this course as one of the overarching and fundamental physical laws. The other two concepts are special cases and only apply under limited conditions. The purpose of this note is to review the pedigree of the Work-Energy Principle, to show how the more general Mechanical Energy Bal- ance is developed from Conservation of Energy, and finally to describe the conditions under which the Mechanical Energy Balance is preferred over the Work-Energy Principle. Work-Energy Principle for a Particle Consider a particle of mass m and velocity V moving in a gravitational field of strength g sub- G ject to a surface force Rsurface . Under these conditions, writing Conservation of Linear Momen- tum for the particle gives the following: d mV= R+ mg (1.1) dt ()Gsurface Forming the dot product of Eq. (1.1) with the velocity of the particle and rearranging terms gives the rate form of the Work-Energy Principle for a particle: 2 dV⎛⎞ d d ⎜⎟mmgzRV+=() surfacei G ⇒ () EEWK += GP mech, in (1.2) dt⎝⎠2 dt dt Gravitational mechanical Kinetic potential power into energy energy the system Recall that mechanical power is defined as WRmech, in= surfaceiV G , the dot product of the surface force with the velocity of its point of application. -

Work-Force Ageing in OECD Countries

CHAPTER 4 Work-force ageing in OECD countries A. INTRODUCTION AND MAIN FINDINGS force ageing, but offset part of the projected fall in labour force growth. 1. Introduction OECD labour markets have adapted to signi®- cant shifts in the age structure of the labour force in Expanding the range and quality of employ- the past. However, the ageing projected over the ment opportunities available to older workers will next several decades is outside the range of recent become increasingly important as populations age historical experience. Hence, it is uncertain how eas- in OECD countries. Accordingly, there is a need to ily such a large increase in the supply of older work- understand better the capacity of labour markets to ers can be accommodated, including the implica- adapt to ageing work forces, including how it can be tions for the earnings and employment of older enhanced. workers. Both the supply and demand sides of the There is only weak evidence that the earnings labour market will be important. It is likely that pen- of older workers are lower relative to younger work- sion programmes and social security systems in ers in countries where older workers represent a many OECD countries will be reformed so that larger share of total employment. This may indicate existing incentives for early retirement will be that workers of different ages are close substitutes reduced or eliminated. Strengthening ®nancial in production, so that an increased supply of older incentives to extend working life, together with a workers can be employed without a signi®cant fall in large increase in the older population and improve- their relative wages.