Work-Force Ageing in OECD Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

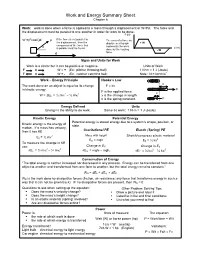

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6 Work: work is done when a force is applied to a mass through a displacement or W=Fd. The force and the displacement must be parallel to one another in order for work to be done. F (N) W =(Fcosθ)d F If the force is not parallel to The area of a force vs. the displacement, then the displacement graph + W component of the force that represents the work θ d (m) is parallel must be found. done by the varying - W d force. Signs and Units for Work Work is a scalar but it can be positive or negative. Units of Work F d W = + (Ex: pitcher throwing ball) 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) F d W = - (Ex. catcher catching ball) Note: N = kg m/s2 • Work – Energy Principle Hooke’s Law x The work done on an object is equal to its change F = kx in kinetic energy. F F is the applied force. 2 2 x W = ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi x is the change in length. k is the spring constant. F Energy Defined Units Energy is the ability to do work. Same as work: 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) Kinetic Energy Potential Energy Potential energy is stored energy due to a system’s shape, position, or Kinetic energy is the energy of state. motion. If a mass has velocity, Gravitational PE Elastic (Spring) PE then it has KE 2 Mass with height Stretch/compress elastic material Ek = ½ mv 2 EG = mgh EE = ½ kx To measure the change in KE Change in E use: G Change in ES 2 2 2 2 ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi ΔEG = mghf – mghi ΔEE = ½ kxf – ½ kxi Conservation of Energy “The total energy is neither increased nor decreased in any process. -

Kinetic Energy and Work

Kinetic Energy and Work 8.01 W06D1 Today’s Readings: Chapter 13 The Concept of Energy and Conservation of Energy, Sections 13.1-13.8 Announcements Problem Set 4 due Week 6 Tuesday at 9 pm in box outside 26-152 Math Review Week 6 Tuesday at 9 pm in 26-152 Kinetic Energy • Scalar quantity (reference frame dependent) 1 K = mv2 ≥ 0 2 • SI unit is joule: 1J ≡1kg ⋅m2/s2 • Change in kinetic energy: 1 2 1 2 1 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 ΔK = mv f − mv0 = m(vx, f + vy, f + vz, f ) − m(vx,0 + vy,0 + vz,0 ) 2 2 2 2 Momentum and Kinetic Energy: Single Particle Kinetic energy and momentum for a single particle are related by 2 1 2 p K = mv = 2 2m Concept Question: Pushing Carts Consider two carts, of masses m and 2m, at rest on an air track. If you push one cart for 3 seconds and then the other for the same length of time, exerting equal force on each, the kinetic energy of the light cart is 1) larger than 2) equal to 3) smaller than the kinetic energy of the heavy car. Work Done by a Constant Force for One Dimensional Motion Definition: The work W done by a constant force with an x-component, Fx, in displacing an object by Δx is equal to the x- component of the force times the displacement: W = F Δx x Concept Q.: Pushing Against a Wall The work done by the contact force of the wall on the person as the person moves away from the wall is 1. -

Feeling Joules and Watts

FEELING JOULES AND WATTS OVERVIEW & PURPOSE Power was originally measured in horsepower – literally the number of horses it took to do a particular amount of work. James Watt developed this term in the 18th century to compare the output of steam engines to the power of draft horses. This allowed people who used horses for work on a regular basis to have an intuitive understanding of power. 1 horsepower is about 746 watts. In this lab, you’ll learn about energy, work and power – including your own capacity to do work. Energy is the ability to do work. Without energy, nothing would grow, move, or change. Work is using a force to move something over some distance. work = force x distance Energy and work are measured in joules. One joule equals the work done (or energy used) when a force of one newton moves an object one meter. One newton equals the force required to accelerate one kilogram one meter per second squared. How much energy would it take to lift a can of soda (weighing 4 newtons) up two meters? work = force x distance = 4N x 2m = 8 joules Whether you lift the can of soda quickly or slowly, you are doing 8 joules of work (using 8 joules of energy). It’s often helpful, though, to measure how quickly we are doing work (or using energy). Power is the amount of work (or energy used) in a given amount of time. http://www.rdcep.org/demo-collection page 1 work power = time Power is measured in watts. One watt equals one joule per second. -

Maximum Frictional Dissipation and the Information Entropy of Windspeeds

J. Non-Equilib. Thermodyn. 2002 Vol. 27 pp. 229±238 Á Á Maximum Frictional Dissipation and the Information Entropy of Windspeeds Ralph D. Lorenz Lunar and Planetary Lab, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA Communicated by A. Bejan, Durham, NC, USA Registration Number 926 Abstract A link is developed between the work that thermally-driven winds are capable of performing and the entropy of the windspeed history: this information entropy is minimized when the minimum work required to transport the heat by wind is dissipated. When the system is less constrained, the information entropy of the windspeed record increases as the windspeed ¯uctuates to dissipate its available work. Fluctuating windspeeds are a means for the system to adjust to a peak in entropy production. 1. Introduction It has been long-known that solar heating is the driver of winds [1]. Winds represent the thermodynamic conversion of heat into work: this work is expended in accelerat- ing airmasses, with that kinetic energy ultimately dissipated by turbulent drag. Part of the challenge of the weather forecaster is to predict the speed and direction of wind. In this paper, I explore how the complexity of wind records (and more generally, of velocity descriptions of thermally-driven ¯ow) relates to the available work and the frictional or viscous dissipation. 2. Zonal Energy Balance Two linked heat ¯uxes drive the Earth's weather ± the vertical transport of heat upwards, and the transport of heat from low to high latitudes. In the present paper only horizontal transport is considered, although the concepts may be extended by analogy into the vertical dimension. -

Work-Energy for a System of Particles and Its Relation to Conservation Of

Conservation of Energy, the Work-Energy Principle, and the Mechanical Energy Balance In your study of engineering and physics, you will run across a number of engineering concepts related to energy. Three of the most common are Conservation of Energy, the Work-Energy Principle, and the Mechanical Engineering Balance. The Conservation of Energy is treated in this course as one of the overarching and fundamental physical laws. The other two concepts are special cases and only apply under limited conditions. The purpose of this note is to review the pedigree of the Work-Energy Principle, to show how the more general Mechanical Energy Bal- ance is developed from Conservation of Energy, and finally to describe the conditions under which the Mechanical Energy Balance is preferred over the Work-Energy Principle. Work-Energy Principle for a Particle Consider a particle of mass m and velocity V moving in a gravitational field of strength g sub- G ject to a surface force Rsurface . Under these conditions, writing Conservation of Linear Momen- tum for the particle gives the following: d mV= R+ mg (1.1) dt ()Gsurface Forming the dot product of Eq. (1.1) with the velocity of the particle and rearranging terms gives the rate form of the Work-Energy Principle for a particle: 2 dV⎛⎞ d d ⎜⎟mmgzRV+=() surfacei G ⇒ () EEWK += GP mech, in (1.2) dt⎝⎠2 dt dt Gravitational mechanical Kinetic potential power into energy energy the system Recall that mechanical power is defined as WRmech, in= surfaceiV G , the dot product of the surface force with the velocity of its point of application. -

3. Energy, Heat, and Work

3. Energy, Heat, and Work 3.1. Energy 3.2. Potential and Kinetic Energy 3.3. Internal Energy 3.4. Relatively Effects 3.5. Heat 3.6. Work 3.7. Notation and Sign Convention In these Lecture Notes we examine the basis of thermodynamics – fundamental definitions and equations for energy, heat, and work. 3-1. Energy. Two of man's earliest observations was that: 1)useful work could be accomplished by exerting a force through a distance and that the product of force and distance was proportional to the expended effort, and 2)heat could be ‘felt’ in when close or in contact with a warm body. There were many explanations for this second observation including that of invisible particles traveling through space1. It was not until the early beginnings of modern science and molecular theory that scientists discovered a true physical understanding of ‘heat flow’. It was later that a few notable individuals, including James Prescott Joule, discovered through experiment that work and heat were the same phenomenon and that this phenomenon was energy: Energy is the capacity, either latent or apparent, to exert a force through a distance. The presence of energy is indicated by the macroscopic characteristics of the physical or chemical structure of matter such as its pressure, density, or temperature - properties of matter. The concept of hot versus cold arose in the distant past as a consequence of man's sense of touch or feel. Observations show that, when a hot and a cold substance are placed together, the hot substance gets colder as the cold substance gets hotter. -

Work, Power, & Energy

WORK, POWER, & ENERGY In physics, work is done when a force acting on an object causes it to move a distance. There are several good examples of work which can be observed everyday - a person pushing a grocery cart down the aisle of a grocery store, a student lifting a backpack full of books, a baseball player throwing a ball. In each case a force is exerted on an object that caused it to move a distance. Work (Joules) = force (N) x distance (m) or W = f d The metric unit of work is one Newton-meter ( 1 N-m ). This combination of units is given the name JOULE in honor of James Prescott Joule (1818-1889), who performed the first direct measurement of the mechanical equivalent of heat energy. The unit of heat energy, CALORIE, is equivalent to 4.18 joules, or 1 calorie = 4.18 joules Work has nothing to do with the amount of time that this force acts to cause movement. Sometimes, the work is done very quickly and other times the work is done rather slowly. The quantity which has to do with the rate at which a certain amount of work is done is known as the power. The metric unit of power is the WATT. As is implied by the equation for power, a unit of power is equivalent to a unit of work divided by a unit of time. Thus, a watt is equivalent to a joule/second. For historical reasons, the horsepower is occasionally used to describe the power delivered by a machine. -

A) B) C) D) 1. Which Is an SI Unit for Work Done on an Object? A) Kg•M/S

1. Which is an SI unit for work done on an object? 10. Which is an acceptable unit for impulse? A) B) A) N•m B) J/s C) J•s D) kg•m/s C) D) 11. Using dimensional analysis, show that the expression has the same units as acceleration. [Show all the 2. Which combination of fundamental units can be used to express energy? steps used to arrive at your answer.] A) kg•m/s B) kg•m2/s 12. Which quantity and unit are correctly paired? 2 2 2 C) kg•m/s D) kg•m /s A) 3. A joule is equivalent to a B) A) N•m B) N•s C) N/m D) N/s C) 4. A force of 1 newton is equivalent to 1 A) B) D) C) D) 13. Which two quantities are measured in the same units? 5. Which two quantities can be expressed using the same A) mechanical energy and heat units? B) energy and power A) energy and force C) momentum and work B) impulse and force D) work and power C) momentum and energy 14. Which is a derived unit? D) impulse and momentum A) meter B) second 6. Which pair of quantities can be expressed using the same C) kilogram D) Newton units? 15. Which combination of fundamental unit can be used to A) work and kinetic energy express the weight of an object? B) power and momentum A) kilogram/second C) impulse and potential energy B) kilogram•meter D) acceleration and weight C) kilogram•meter/second 7. -

Chapter 07: Kinetic Energy and Work Conservation of Energy Is One of Nature’S Fundamental Laws That Is Not Violated

Chapter 07: Kinetic Energy and Work Conservation of Energy is one of Nature’s fundamental laws that is not violated. Energy can take on different forms in a given system. This chapter we will discuss work and kinetic energy. If we put energy into the system by doing work, this additional energy has to go somewhere. That is, the kinetic energy increases or as in next chapter, the potential energy increases. The opposite is also true when we take energy out of a system. the grand total of all forms of energy in a given system is (and was, and will be) a constant. Exam 2 Review • Chapters 7, 8, 9, 10. • A majority of the Exam (~75%) will be on Chapters 7 and 8 (problems, quizzes, and concepts) • Chapter 9 lectures and problems • Chapter 10 lecture Different forms of energy Kinetic Energy: Potential Energy: linear motion gravitational rotational motion spring compression/tension electrostatic/magnetostatic chemical, nuclear, etc.... Mechanical Energy is the sum of Kinetic energy + Potential energy. (reversible process) Friction will convert mechanical energy to heat. Basically, this (conversion of mechanical energy to heat energy) is a non-reversible process. Chapter 07: Kinetic Energy and Work Kinetic Energy is the energy associated with the motion of an object. m: mass and v: speed SI unit of energy: 1 joule = 1 J = 1 kg.m2/s2 Work Work is energy transferred to or from an object by means of a force acting on the object. Formal definition: *Special* case: Work done by a constant force: W = ( F cos θ) d = F d cos θ Component of F in direction of d Work done on an object moving with constant velocity? constant velocity => acceleration = 0 => force = 0 => work = 0 Consider 1-D motion. -

Kinetic Energy and the Work-Energy Principle

Class 15 Quiz on Wednesday. Sec 202 will meet in Pasteur 301, around the corner from the Tutoring center in Southwick Wed. Clicker Question. Kinetic Energy and the Work-Energy Principle The definition of Energy Energy is different from all other concepts in physics in that there is no single definition for it. Instead there are many different kinds of energy. Kinetic Energy Kinetic energy is energy associated with motion. If we uses Newton's laws to compute the work done in accelerating an object, over a certain distance, it turns out that the work is 1 1 W = mv 2− m v 2 net 2 2 2 1 If we define kinetic energy as 1 KE= m v2 2 the result is the work-energy principle The work done in changing the state of motion of an object is equal to the change in the kinetic energy. W net =KE 2−KE 1= KE This relationship is not anything which is not contained in Newton's laws, it is a restatement in terms of energy, and make many problems much easier to solve. 1 Class 15 Potential Energy While Kinetic energy is associated with motion potential energy is associated with position. Whereas kinetic energy has an obvious zero, when the velocity is zero, potential energy is only defined as a change. Potential energy itself has come in different kinds. Gravitational Potential Energy As with kinetic energy we start with the net work done when we lift an object, without any acceleration. If we calculate the work done by an external force in lifting the object shown above we get W ext=F ext d cos0=mg∗ y2− y1 (6.) We can also compute the work done by gravity in the same process. -

SCOPE of WORK for DIESEL FUEL SUPPLY and DELIVERY in SUPPORT of NATO E-3A COMPONENT at GEILENKIRCHEN, GERMANY

20-May-20 Version 4.0 SCOPE OF WORK For DIESEL FUEL SUPPLY AND DELIVERY IN SUPPORT OF NATO E-3A COMPONENT AT GEILENKIRCHEN, GERMANY This document contains NSPA proprietary information. Reproduction or disclosure of any part without prior approval by NSPA is not permitted. Page 1 of 12 NATO UNCLASSIFIED AMENDMENT RECORD REVISION/AMENDMENT PAGES DATE OF ISSUE REMARKS Version 1.0 15 07/05/2020 Draft NSPA review Version 2.0 15 13/05/2020 Customer review (LWSDP) Version 3.0 12 14/05/2020 NSPA review Version 4.0 12 20/05/2020 NSPA review Page 2 of 12 NATO UNCLASSIFIED TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Scope ................................................................................................................................. 5 2. Applicable Documents ........................................................................................................5 3. Command and Control .......................................................................................................5 4. Planning Factors / Constraints ............................................................................................ 6 5. Description of the Services Required ..................................................................................6 6. Schedules, Milestones and Operating Hours ......................................................................8 7. Contractor Human Resources Required, Qualifications, and Language Skills .................... 8 8. NSPA / Customer Furnished Facilities, Equipment, Tools and Supplies ............................. 8 9. -

Circuits and Electricity

Circuits and Electricity 5.6B Have you ever thought about how much we depend on electricity? Electricity is a form of energy that runs computers, appliances, and radios. Electricity lights our homes, schools, and office buildings. Without it, our world would be a much different place. In fact, before electricity was discovered, people mainly used fire to cook and to provide light and heat. Electricity has become an important part of our lives. You might know that the use of electricity often involves wires. But how do energy: the ability to you think electricity travels through these wires? How does it do work produce other kinds of energy like light, heat, and sound? How does electricity travel? All matter is made up of particles. Electrical energy is energy produced by the movement of certain particles. This flow of particles is called electric current. So what does this have to do with lights, appliances, and computers? In order to light a light bulb or turn on a computer, we need to produce a continuous electric current. To do this, we need an energy source. Common energy sources include batteries and generators. You’ll learn more about these shortly. An electric current also needs a path along which it can travel. An electric circuit is Electric current flows through an a pathway through which electric current flows. electric circuit like this one. Now you know that electric current flows through a path called a circuit. You also know that a continuous electric current needs an energy source such as a battery. What else is needed to make a circuit? What is necessary to have energy flow through a circuit? You can think of a circuit as a loop.