Michael Lansdown, 'The Lloyds Bank Facade at Trowbridge and Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addendum to School Places Strategy 2017-2022 – Explanation of the Differences Between Wiltshire Community Areas and Wiltshire School Planning Areas

Addendum to School Places Strategy 2017-2022 – Explanation of the differences between Wiltshire Community Areas and Wiltshire School Planning Areas This document should be read in conjunction with the School Places Strategy 2017 – 2022 and provides an explanation of the differences between the Wiltshire Community Areas served by the Area Boards and the School Planning Areas. The Strategy is primarily a school place planning tool which, by necessity, is written from the perspective of the School Planning Areas. A School Planning Area (SPA) is defined as the area(s) served by a Secondary School and therefore includes all primary schools in the towns and surrounding villages which feed into that secondary school. As these areas can differ from the community areas, this addendum is a reference tool to aid interested parties from the Community Area/Area Board to define which SPA includes the schools covered by their Community Area. It is therefore written from the Community Area standpoint. Amesbury The Amesbury Community Area and Area Board covers Amesbury town and surrounding parishes of Tilshead, Orcheston, Shrewton, Figheldean, Netheravon, Enford, Durrington (including Larkhill), Milston, Bulford, Cholderton, Wilsford & Lake, The Woodfords and Great Durnford. It encompasses the secondary schools The Stonehenge School in Amesbury and Avon Valley College in Durrington and includes primary schools which feed into secondary provision in the Community Areas of Durrington, Lavington and Salisbury. However, the School Planning Area (SPA) is based on the area(s) served by the Secondary Schools and covers schools in the towns and surrounding villages which feed into either The Stonehenge School in Amesbury or Avon Valley College in Durrington. -

Sutton Veny Best Kept Villages

Sutton Veny Best Kept Villages Villages clean up at contest The finalists of the Best Kept Village in west Wiltshire have been named. Bratton came top in the large village section, beating Atworth, Bowerhill, Holt and North Bradley, while Sutton Veny was judged the best medium village, finishing ahead of Edington, Horningsham, Shaw and Whitely. Best small village is Chitterne, which saw off competition from Beanacre, Bishopstrow and Boreham, Brokerswood, Coulston and Great Hinton. Chairman of Chitterne Parish Council, Jeremy Reid said: "We are absolutely delighted. The people who work voluntarily are the ones who made it possible." Chitterne was the only village of the three not to have received the same accolade two years running. The last time they won was in 1997. Cllr Reid said: "We listened to the judges last time and we have made some improvements. "We changed the position of the notice board and we did restoration work on the recreation ground." The three winners will now go through to the county final, which will be judged later this summer. Chairman of Sutton Veny Parish Council, Tony Henthorne said: "We have a core group of people who have helped and they did a sterling job of cleaning the village and making it tidy. "We are looking forward to the next round of the competition and hopefully we will have better luck than we did last year." Clerk of Bratton Parish Council, Anita Whittle said: "We are very pleased. Everyone is delighted. "Special thanks must go to the village handyman, Bob Jordan who has been tidying all the village lanes. -

Wiltshire PARO SOPN

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED & NOTICE OF POLL Election of a Police and Crime Commissioner Wiltshire PCC Police Area A poll will be held on 5 May 2016 between 7am and 10pm The following people have been or stand nominated for election as a Police and Crime Commissioner for the above police area. Those who no longer stand nominated are listed, but will have a comment in the right hand column. If candidate no Address of candidate 1 Description of longer Candidate name candidate nominated, reason why MACPHERSON (address in Swindon The Conservative Party Angus (South) Parliamentary Candidate Constituency) MATHEW The Old School, The Liberal Democrat Brian George Street, Yatton Keynell, Felton Chippenham, Wiltshire, SN14 7BA SHORT 225 Marlborough Rd United Kingdom John Swindon SN3 1NN Independence Party SMALL 9 Jennings Street, Labour Party Kevin David Swindon, SN2 2BQ 1 or, if a candidate has requested not to have their home address made public, the name of their electoral area. Dated Thursday 7 April 2016 Stephen P. Taylor Police Area Returning Officer Printed and published by the Police Area Returning Officer, Civic Offices, Euclid Street, Swindon, SN1 2JH Police and Crime Commissioner Election Situation of polling stations Police area name: Wiltshire Voting area name: Wiltshire Council No. of polling Situation of polling station Description of persons entitled station to vote 1 Mount Pleasant Centre, 1A Mount Pleasant, EH1-1 to EH1-1053 Bradford On Avon 2 Lambert Community Centre, Mount Pleasant, EH2-1 to EH2-614 Bradford On Avon, Wiltshire -

Press Release 8Th August 2014

Press Release 8th August 2014 The Hills Group CPRE Wiltshire Best Kept Village Competition 2014 This judging of this year’s Hills Group CPRE Wiltshire Best Kept Village Competition, sponsored by the Hills Group, is now complete. The First Round of the competition saw the expert judging teams from the Wiltshire Branch of the Campaign to Protect Rural England putting each village under the microscope. 51 villages throughout the county were tested against the competition criteria which look for tidiness, cleanliness, presentation and village community spirit. The parish councils and their volunteers had clearly been hard at work, achieving encouragingly high standards and making the judges’ task that much more difficult. Each village is judged within the categories of ‘Small’, ‘Medium’ and ‘Large’ and in the First Round they are only judged within their own district: West Wiltshire, North Wiltshire, South Wiltshire, Kennet and Swindon Borough. The winning villages in each district were then judged against each other in the County Round, using fresh judging teams including individual judges from Wiltshire Council. The final results were: Large Village Medium Village Small Village 1st Blunsdon 1st Mildenhall 1st Stapleford 2nd Whiteparish 2nd Liddington 2nd Charlton 3rd Holt 3rd Biddestone 3rd = Bishopstrow 4th Box 4th = Maiden Bradley Rushall 5th Aldbourne Sutton Veny A quote from one of the judging teams reflects just how high the standard of this year’s competition was: “The overall standard of the villages was very good, and deciding on a winner was very difficult, only 6 points separated all the villages and the majority of category scores were 5 or 6 (better than good)” Each winning village will be presented with, and keep, an eight foot standard with mounted shield for a year emplaced on their village green. -

Service 76/77 Trowbridge

Service 76/77 Trowbridge - Steeple Ashton - Worton - Devizes Effective from 1st March 2021 FB FB Mondays to Fridays 77 63 77 76 76 87A 87 87A 76 76 77 77 77 Devizes, Market Place, The Pelican 0741W — 0950B 1210 1410 1515 1750B Trowbridge, Wiltshire College — — — — WR 1700 Bath Road, Business Centre — — — 1214 1414 1519 — Trowbridge, Manvers Street 0705 0945 1225 1425 1605 1710 Mayenne Place West — — — RR — — Paxcroft Mead, Layby E 0950 1230 1430 1610 1715 Poulshot, The Raven — — — 1219 R 1524 — Steeple Ashton, Memorial E 0959 1239 1439 1619 1723R Potterne, Porch House 0745 — 0955 — — — 1755 Great Hinton crossroads E 1002 1242 1442 1622 1725 Worton, Sandleaze 0749 — 0959 1227 R 1533 R Keevil E 1005 1245 1445 1625 1727 Worton, Village Hall 0751 — 1001 1229 R 1531 R Bulkington, Memorial E 1010 1250 1450 1630 1732 Marston, The Green — — — RRE — Worton, Sandleaze 0747 1016 1256 1457x 1638x 1740x Bulkington, Memorial 0757 — 1007 1237 RE — Worton, Village Hall 0749 1018 1258 1455x 1636x 1738x Keevil 0802 — 1012 1242 RE — Marston, The Green — 1023 1303 — — — Great Hinton crossroads 0805 — 1015 1245 RE — Potterne, Porch House — — — 1501 1642 1744 Steeple Ashton, Memorial 0808 0903 1018 1248 R E — Poulshot, The Raven 0754 1030 1310 — — — Paxcroft Mead, Layby 0813 0910 1025 1255 — E — Mayenne Place, west — 1034 1314 — — — Trowbridge, Manvers Street 0828 0920‡ 1031 1301 — 1619 — Bath Road Business Centre 0758 1035 1315 DS —— ▼ Devizes, Market Place 0808 1039 1319 1515 1647 1749 DS Saturdays 77 76 76 76 87 87A 76 76 76 77 877 Devizes, Market Place, -

Wiltshire Parishes

Wiltshire Parishes Marston Maisey CP Latton CP Ashton Keynes CP Oaksey CP Crudwell CP Cricklade CP Leigh CP Minety CP Hankerton CP Brokenborough CP Charlton CP Purton CP Braydon CP Malmesbury CP Easton Grey CP Sopworth CP Lea and Cleverton CP Sherston CP Lydiard Millicent CP Norton CP St. Paul Malmesbury Without CP Little Somerford CP Brinkworth CP Lydiard Tregoze CP Luckington CP Hullavington CP Great Somerford CP Dauntsey CP Royal Wootton Bassett CP Seagry CP Stanton St. Quintin CP Tockenham CP Grittleton CP Christian Malford CP Broad Town CP Lyneham and Bradenstoke CP Sutton Benger CP Nettleton CP Kington St. Michael CP Castle Combe CP Clyffe Pypard CP Baydon CP Kington Langley CP Broad Hinton CP Yatton Keynell CP Aldbourne CP Langley Burrell Without CP North Wraxall CP Hilmarton CP Chippenham Without CP Bremhill CP Ogbourne St. George CP Winterbourne Bassett CP Biddestone CP Berwick Bassett CP Ogbourne St. Andrew CP Chippenham CP Compton Bassett CP Colerne CP Winterbourne Monkton CP Ramsbury CP Chilton Foliat CP Calne CP Preshute CP Cherhill CP Mildenhall CP Corsham CP Calne Without CP Avebury CP Marlborough CP Lacock CP Fyfield CP Box CP Froxfield CP West Overton CP East Kennett CP Little Bedwyn CP Heddington CP Melksham Without CP Savernake CP Bromham CP Atworth CP Monkton Farleigh CP Bishops Cannings CP Melksham CP Huish CP South Wraxall CP Broughton Gifford CP Great Bedwyn CP All Cannings CP Alton CP Wootton Rivers CP LCPs of Broughton Gifford and Melksham Without Stanton St. Bernard CP Rowde CP Roundway CP Wilcot CP Shalbourne -

Rural Housing Needs Surveys – Status Map Last Updated April 2021

Rural Housing Needs Surveys – Status Map Last Updated April 2021 Complete (from 2016) Awaiting (Programmed) 60 Cholderton 132 Lacock 203 South Wraxall St. Paul Malmesbury ID Name 61 Christian Malford 134 Langley Burrell Without 205 Without 1 Aldbourne No Current Survey 62 Chute 135 Latton 206 Stanton St. Bernard 11 Avebury 2 Alderbury 63 Chute Forest 136 Laverstock 208 Stapleford 12 Barford St. Martin 3 All Cannings 64 Clarendon Park 138 Leigh 209 Staverton 24 Box 4 Allington 68 Collingbourne Ducis 139 Limpley Stoke 210 Steeple Ashton 27 Bratton 5 Alton 69 Collingbourne Kingston 140 Little Bedwyn 211 Steeple Langford 37 Bromham 6 Alvediston 70 Compton Bassett 141 Little Somerford 212 Stert 58 Chirton and Conock 7 Amesbury 71 Compton Chamberlayne 142 Longbridge Deverill 213 Stockton 65 Clyffe Pypard 8 Ansty 73 Corsham 143 Luckington 215 Stratford Toney 66 Codford 9 Ashton Keynes 75 Coulston 144 Ludgershall 216 Sutton Benger 67 Colerne 10 Atworth 76 Cricklade 145 Lydiard Millicent 217 Sutton Mandeville 72 Coombe Bissett 13 Baydon 77 Crudwell 146 Lydiard Tregoze 218 Sutton Veny Maiden Bradley with 74 Corsley 14 Beechingstoke 78 Dauntsey 148 Yarnfield 219 Swallowcliffe 80 Dilton Marsh 15 Berwick Bassett 79 Devizes 149 Malmesbury 220 Teffont 92 Edington 16 Berwick St. James 81 Dinton 150 Manningford 222 Tidcombe and Fosbury 106 Great Bedwyn 17 Berwick St. John 82 Donhead St. Andrew 151 Marden 223 Tidworth 107 Great Durnford 18 Berwick St. Leonard 83 Donhead St. Mary 153 Marlborough 224 Tilshead 116 Heytesbury 19 Biddestone 84 Downton 154 Marston 226 Tockenham 117 Heywood 20 Bishops Cannings 85 Durrington 155 Marston Maisey 227 Tollard Royal 118 Hilmarton 21 Bishopstone 86 East Kennett 156 Melksham 228 Trowbridge 119 Hilperton 22 Bishopstrow 87 East Knoyle 157 Melksham Without 229 Upavon 120 Hindon 23 Bowerchalke 88 Easterton 159 Mildenhall 230 Upton Lovell 121 Holt 25 Boyton 89 Easton 160 Milston 231 Upton Scudamore 124 Hullavington 26 Bradford-on-Avon 90 Easton Grey 161 Milton Lilbourne 232 Urchfont 130 Kington St. -

COVID-19 Community Groups Directory INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 Community Groups Directory INTRODUCTION The communities of Wiltshire have risen to the challenge of COVID-19 to make sure people are supported through this very difficult time. The council has collated all the community groups we have identified so far so that those who need support for themselves or a loved one can make direct contact. In the time available we have only been able to collate this directory and therefore this is not an endorsement of the groups listed but it is for you to decide what use you will make of the offers of support at this time. If anyone uses a community group and has concerns about the response/practice please inform us by emailing [email protected] giving the clear reasons for your concern. The council wants to ensure that everybody can access the support they need. If you make contact with a group and they cannot help or you do not get a response within the required timeframe, then please do not hesitate to contact the council by emailing [email protected] and we will ensure you get the support you need. SERVICES THEY ARE PROVIDING? NAME OF COMMUNITY ORGANISATION/ AREA COVERED (e.g. shopping, prescription pick up, CONTACT DETAILS AREA (Street, parish, town) INDIVIDUAl information and advice, outreach to vulnerable/ elderly) www.amesburyhub.com Amesbury General volunteer support Amesbury Amesbury 01980 622525 Community Hub online (food/shopping/medical) [email protected]. Amesbury multi Amesbury town and some Amesbury Gathering information [email protected] agency group -

Covid-19 Community Directory

COVID-19 COMMUNITY GROUPS DIRECTORY Last updated 26 March 2020 DM20_295 ONLINE INTRODUCTION The communities of Wiltshire have risen to the challenge of COVID-19 to make sure people are supported through this very difficult time. The council has collated all the community groups we have identified so far so that those who need support for themselves or a loved one can make direct contact. In the time available we have only been able to collate this directory and therefore this is not an endorsement of the groups listed but it is for you to decide what use you will make of the offers of support at this time. If anyone uses a community group and has concerns about the response/practice please inform us by emailing [email protected] giving the clear reasons for your concern. The council wants to ensure that everybody can access the support they need. If you make contact with a group and they cannot help or you do not get a response within the required timeframe, then please do not hesitate to contact the council by emailing [email protected] and we will ensure you get the support you need. SERVICES THEY ARE PROVIDING? NAME OF COMMUNITY AREA COVERED ORGANISATION/ (e.g. shopping, prescription/medication CONTACT DETAILS AREA (Street, parish, town) INDIVIDUAL pick up, information and advice, outreach to vulnerable/ elderly) General volunteer support www.amesburyhub.com Amesbury Amesbury Amesbury (food shopping shopping, 01980 622525 Community Hub prescription/medication) [email protected]. Amesbury multi Amesbury town -

Capital in the Countryside: Social Change in West Wiltshire, 1530-1680

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Capital in the countryside: social change in West Wiltshire, 1530-1680 https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40143/ Version: Full Version Citation: Gaisford, John (2015) Capital in the countryside: social change in West Wiltshire, 1530-1680. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email 1 Capital in the Countryside: Social Change in West Wiltshire, 1530-1680 John Gaisford School of History, Classics and Archaeology Birkbeck, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 The work presented in this thesis is my own. ©John Gaisford 2015 2 Abstract West Wiltshire in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was among the leading producers of woollen cloth, England’s most important export commodity by far, but the region’s importance is often understated by modern historians. The cloth towns of Bradford-on-Avon, Trowbridge and Westbury were thriving when John Leland visited in 1540; but GD Ramsay thought they had passed their golden age by 1550 and declined during the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Joan Thirsk – following the precedent of John Aubrey, who wrote a survey of north Wiltshire in the 1660s – characterised the region as ‘cheese country’. Based on new archival research, this thesis argues that, far from declining, cloth manufacture in west Wiltshire grew throughout the Tudor era and remained strong under the early Stuarts; that production of this crucial trade commodity gave the region national significance; and that profits from the woollen trade were the main drivers of change in west Wiltshire over the period 1530-1680. -

Newsletter Great Hinton February 2019

Anne-Marie fund raising STEEPLE ASHTON at the Christmas Tree Festival see p38 NEWSLETTER GREAT HINTON FEBRUARY 2019 Father Christmas visits Steeple Ashton The Baptism of Avalynn Louise Barrington on Sunday 20th January 2019 in St Mary’s Church, Steeple Ashton Steeple Ashton Village Shop Opening hours: Monday to Friday 7.30am to 5.30pm Saturday 8.30am to 4.30pm; Sunday 9.00am to 12noon Shop telephone: 01380 871 211 CONTENTS STEEPLE ASHTON PARISH COUNCIL February 2019 Pages 35 Catholic News VACANCY – STEEPLE ASHTON PARISH CLERK 1 Church Services Steeple Ashton Parish Council has a vacancy for parish clerk and responsi- 29 Edington Arts ble financial officer. 10 Films 8 Forget-me-Nots The job, which is part time will involve: 20-21 Friends of SA • Acting as secretary to the formal meetings – attending monthly evening 30 From the Archives meetings 38 Keevil Theatre Group • Dealing with correspondence and finance on behalf of the council 29 Keevil Folk Night • Providing advice to the council in respect of regulatory matters 34-35 Methodist Church 12-13 Natural History Group The applicant will be: 39-40 Parish Council Equipped with high standards of numeracy and literacy 37 Preservation Trust Efficient, well organised, proactive, self-motivated and enjoy working alone 9 Shop without day-to-day supervision 2-7 St Mary’s Church Computer literate with proficiency in Word, Excel, email and use of the Inside Back Cover Vacancy, Parish Clerk internet 33 Village Diary Interested in the workings of the village, and willing to ‘go the extra mile’ 14 Weather Report 34 World Day of Prayer This role is part time (10 - 12 hours per week) and can be flexible in how the 8, 32 WI hours are worked (subject to fixed deadlines and meeting dates). -

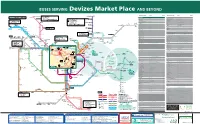

Devizes Spider 1033X652

BUSES SERVING Devizes Market Place AND BEYOND Destination finder Route Stand Destination finder Route Stand Chippenham Station Change at Chippenham for: Swindon Station 49 55 to Wootton Bassett RUH Hopper bus for Royal United Hospital, Bath C2W 33 X33 DEVIZES H bookable service fromom Devizes TTeel 08456 52 52 55 OOption 2 92 to Malmesbury Chippenham 231, 232 to Corsham Alan Cobham Road 1A C Hawkstreet, Bromham Seend Shuttle A Change at Swindon for: Swindon 234, X34 & D to Chippenham Community Hospital Bath Road 49 77 85 87A 271 272 273 X72 A Heathrow Airport National Express 402 E to Great Western Hospital BitBristol lT Temple Meads and Flyer for Bristol Airport 16 Brickley Lane Heytesbury 55 B Change at Bath for: 31 to Malmesbury 14 to Bath Royal United Hospital 55 to Cirencester and Cheltenham Jump Farm Roundabout 1A 1C C Heywood 87 A Wroughton High Street 339, X39 to Bristol 66 to Faringdon and Oxford Broadleas Road 1A C Hilcott Connect2: Lines 1 & 2 D Derry Hill London Bristol for Bristol Airport Flyer Cheltenham andan Cardiff London Victoria Caen Hill: Holt 39 A Reading for Gatwick and RailAir bus to Heathrow Batheaston London Earl’s Court Coach Station A361 Poulshot turning 49 85 87A 271 272 273 X72 A Honeystreet Connect2: Lines 1 & 2 D London PaddinPaddington Broad Hinton High Street 33 Heathrow Airport Cromwell Road 1A C Horton Connect2: Line 1 D Bell 49 Bath Box 402 Devizes School 87A X72 C K Northey Arms X33 Downlands Road 1A B Calne Winterbourne Bassett Keevil 77 85 A Change at Calne for: Eastleigh Road 1A C 271 272 55 to