The Challenge of Archaeological Interpretation and Practice That Integrates Between the Science of the Past and Local Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Site Surveying Techniques Bibliography

HANDOUT 1 – Basic Site Surveying Techniques [8/2015] Bibliography & Suggested Reading Ammerman, Albert J. 1981 Surveys and Archaeological Research. Annual Review of Anthropology 10:63–88. Anderson, James M., and Edward M. Mikhail 1998 Surveying: Theory and Practice. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill Science/ Engineering/Math, Columbus, OH. Banning, Edward B. 2002 Archaeological Survey. Manuals in Archaeological Method, Theory and Technique. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York. Banning, Edward B., A. L. Hawkins, and S. T. Stewart 2006 Detection Functions for Archaeological Survey. American Antiquity 71(4):723–742. Billman, Brian R., and Gary M. Feinman (editors) 1999 Settlement Patterns in the Americas: Fifty Years Since Virú. Smithsonian Institution Press, Herndon, VA. Black, Kevin D. 1994 Archaeology of the Dinosaur Ridge Area. Friends of Dinosaur Ridge, Colorado Historical Society, Colorado Archaeological Society and Morrison Natural History Museum. Morrison, CO. Burger, Oskar, Lawrence C. Todd, Paul Burnett, Tomas J. Stohlgren, and Doug Stephens 2002–2004 Multi-Scale and Nested-Intensity Sampling Techniques for Archaeological Survey. Journal of Field Archaeology 29(3 & 4):409–423. Burke, Heather, Claire Smith, and Larry J. Zimmerman 2009 The Archaeologist’s Field Handbook: North American Edition. AltaMira Press, Lanham, Maryland. Collins, James M., and Brian Leigh Molyneaux 2003 Archaeological Survey. Archaeologist’s Toolkit Volume 2. Altamira Press, Lanham, MD. Fagan, Brian M. 2009 In the Beginning: An Introduction to Archaeology. 12th ed. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. Fish, Susanne K., and Steven A. Kowalewski (editors) 1989 The Archaeology of Regions: A Case for Full-Coverage Survey. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C. Gallant, T. W. 1986 “Background Noise” and Site Definition: a Contribution to Survey Methodology. -

Amy R. Michael, Ph.D. 10 Portland St

Amy R. Michael, Ph.D. 10 Portland St. Somersworth, NH 03878 [email protected] 309-264-4182 amymichaelosteo.wordpress.com anthropology.msu.edu/cbasproject EDUCATION 2016 Ph.D. in Anthropology, Michigan State University Dissertation: Investigations of Micro- and Macroscopic Dental Defects in Pre-Hispanic Maya Cave and Rockshelter Burials in Central Belize 2009 M.A. in Anthropology, Michigan State University 2006 B.A. in Anthropology, University of Iowa RESEARCH INTERESTS Bioarchaeology, forensic anthropology, Maya archaeology, taphonomy, histology, dental anthropology, identification of transgender and gender variant decedents, public archaeology, archaeology of gender, human variation, growth and development, paleopathology, effects of drugs and alcohol on skeletal microstructure, cold cases, intersections of biological anthropology and social justice RESEARCH SKILLS AND TRAINING Mentorship and advising undergraduate and graduate students, NAGPRA repatriation, community outreach and public archaeology, curricular development, transmitted light microscopy, histology, forensic archaeology, Fordisc, SPSS, OsteoWare, rASUDAS, ImageJ ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT 2018-present Lecturer in Anthropology, University of New Hampshire 2017-present Research Affiliate for Center for Archaeology, Materials, and Applied Spectroscopy (CAMAS), Idaho State University 2017-2018 Visiting Assistant Professor of Anthropology, Idaho State University 2017 Visiting Assistant Professor of Anthropology, Albion College 2016-present Instructor of Anthropology, Lansing -

A New Method of Classification for Tai Textiles

A New Method of Classification for Tai Textiles Patricia Cheesman Textiles, as part of Southeast Asian traditional clothing and material culture, feature as ethnic identification markers in anthropological studies. Textile scholars struggle with the extremely complex variety of textiles of the Tai peoples and presume that each Tai ethnic group has its own unique dress and textile style. This method of classification assumes what Leach calls “an academic fiction … that in a normal ethnographic situation one ordinarily finds distinct tribes distributed about the map in an orderly fashion with clear-cut boundaries between them” (Leach 1964: 290). Instead, we find different ethnic Tai groups living in the same region wearing the same clothing and the same ethnic group in different regions wearing different clothing. For example: the textiles of the Tai Phuan peoples in Vientiane are different to those of the Tai Phuan in Xiang Khoang or Nam Nguem or Sukhothai. At the same time, the Lao and Tai Lue living in the same region in northern Vietnam weave and wear the same textiles. Some may try to explain the phenomena by calling it “stylistic influence”, but the reality is much more profound. The complete repertoire of a people’s style of dress can be exchanged for another and the common element is geography, not ethnicity. The subject of this paper is to bring to light forty years of in-depth research on Tai textiles and clothing in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Laos), Thailand and Vietnam to demonstrate that clothing and the historical transformation of practices of social production of textiles are best classified not by ethnicity, but by geographical provenance. -

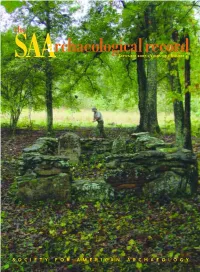

The SAA Archaeological Record (ISSN 1532-7299) Is Published five Times a Year Andrew Duff and Is Edited by Andrew Duff

the archaeologicalrecord SAA SEPTEMBER 2007 • VOLUME 7 • NUMBER 4 SOCIETY FOR AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY the SAAarchaeologicalrecord The Magazine of the Society for American Archaeology Volume 7, No. 4 September 2007 Editor’s Corner 2 Andrew Duff Letters to the Editor 3 From the President 6 Dean R. Snow In Brief 7 Tobi A. Brimsek Archaeopolitics 8 Dan Sandweiss and David Lindsay Probing during cemetery Vancouver in 2008 9 Dana Lepofsky, Sue Rowley, delineation in Coweta Andrew Martindale, County, Georgia. and Alan McMillan Photo by Ron Hobgood. RPA: The Issue of Commercialism: Proposed Changes 10 Jeffrey H. Altschul to the Register’s Code of Conduct Archaeology’s High Society Blues: Reply to McGimsey 11 Lawrence E. Moore Amerind-SAA Seminars: A Progress Report 15 John A. Ware Email X and the Quito Airport Archaeology 20 Douglas C. Comer Controversy: A Cautionary Tale for Scholars in the Age of Rapid Information Flow Identifying the Geographic Locations 24 German Loffler in Need of More CRM Training Can the Dissertation Be All Things to All People? 29 John D. Rissetto Networks: Historic Preservation Learning Portal: 33 Richard C. Waldbauer, Constance Werner Ramirez, A Performance Support Project for and Dan Buan Cultural Resource Managers Interfaces: 12V 35 Harold L. Dibble, Shannon J.P. McPherron, and Thomas McPherron Heritage Planning 42 Yun Shun Susie Chung In Memoriam: Jaime Litvak King 47 Emily McClung de Tapia and Paul Schmidt Calls for Awards Nominations 48 positions open 52 news and notes 54 calendar 56 EDITOR’S CORNER the SAAarchaeologicalrecord The Magazine of the Society for American Archaeology Volume 7, No. -

Tau Tae Tching Or Lao-Tse (The Right Path)

TAl CULTURE Vol. 20 Tai peoples in ChinaChina.. Part III _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Oliver Raendchen * TAI ANCIENT PHILOSOPHY: tau tae tching or lao-tse (The Right Path) Abstract In this essay, ancient Tai philosophy (way of life; perception of the world) is approached in a specific way. Following more than 20 years of his comparative and interdisciplinary study in the ancient philosophy expressed in the tau tae tching text on the one hand and the world view, way of life and practical behavior of the Tai peoples on the other hand, the author has been developing the firm belief that the ancient philosophical text tau tae tching - which is found in old written exemplars in the Chinese language and attributed to Laotse - is most probably rooted in the ancient traditions and philosophy of the Tai peoples whose forefathers settled in historical times in what is today South China. In the opinion of the author, the written philosophical text tau tae tching was created as a mirror, as a secondary image, of an existing culture, namely, the world view, way of life, and practical rules of behavior of the Tai peoples. Compared to the concrete behavioural rules, traditional laws, etc., of the Tai peoples, the tau tae tching is a philosophical condensation and abstraction. It is something like a bible of behavioural norms and was used not only for worshipping the holy “right path” of behaviour, but in fact represents a complete value system which reinforced the social order. As such, it was also the source for intellectuals to compete with other value systems (e.g., that of Confucius) which was followed by other ethnic groups, namely the Han-Chinese. -

North Carolina Archaeology

North Carolina Archaeology Volume 65 2016 North Carolina Archaeology Volume 65 October 2016 CONTENTS Don’t Let Ethics Get in the Way of Doing What’s Right: Three Decades of Working with Collectors in North Carolina I. Randolph Daniel, Jr. ......................................................................................... 1 Mariners’ Maladies: Examining Medical Equipage from the Queen Anne’s Revenge Shipwreck Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton ........................................................................... 28 Archival Excavations from Dusty File Cabinets, Part I: Unpublished Artifact Pattern Data of Colonial Period Households, Dependency Buildings, and Public Structures from Colonial Brunswick Town Thomas E. Beaman, Jr. ...................................................................................... 53 Preface: Identifying and Defining North Carolina’s Archaeological Heritage through Remote Sensing and Geophysics John J. Mintz and Shawn M. Patch .................................................................... 90 The Role of GPR in Archaeology: A Beginning Not an End Charles R. Ewen ................................................................................................. 92 Three-dimensional Remote Sensing at House in the Horseshoe State Historic Site (31MR20), Moore County, North Carolina Stacy Curry and Doug Gallaway ..................................................................... 100 An Overview of Geophysical Surveys and Ground-truthing Excavations at House in the Horseshoe (31MR20), Moore County, North -

Chiang Mai Lampang Lamphun Mae Hong Son Contents Chiang Mai 8 Lampang 26 Lamphun 34 Mae Hong Son 40

Chiang Mai Lampang Lamphun Mae Hong Son Contents Chiang Mai 8 Lampang 26 Lamphun 34 Mae Hong Son 40 View Point in Mae Hong Son Located some 00 km. from Bangkok, Chiang Mai is the principal city of northern Thailand and capital of the province of the same name. Popularly known as “The Rose of the North” and with an en- chanting location on the banks of the Ping River, the city and its surroundings are blessed with stunning natural beauty and a uniquely indigenous cultural identity. Founded in 12 by King Mengrai as the capital of the Lanna Kingdom, Chiang Mai has had a long and mostly independent history, which has to a large extent preserved a most distinctive culture. This is witnessed both in the daily lives of the people, who maintain their own dialect, customs and cuisine, and in a host of ancient temples, fascinating for their northern Thai architectural Styles and rich decorative details. Chiang Mai also continues its renowned tradition as a handicraft centre, producing items in silk, wood, silver, ceramics and more, which make the city the country’s top shopping destination for arts and crafts. Beyond the city, Chiang Mai province spreads over an area of 20,000 sq. km. offering some of the most picturesque scenery in the whole Kingdom. The fertile Ping River Valley, a patchwork of paddy fields, is surrounded by rolling hills and the province as a whole is one of forested mountains (including Thailand’s highest peak, Doi Inthanon), jungles and rivers. Here is the ideal terrain for adventure travel by trekking on elephant back, river rafting or four-wheel drive safaris in a natural wonderland. -

Nadia CV 09:17:19

Nadia C. Neff, PhD Student Department of Anthropology [email protected] University of New Mexico (970) 488 – 9932 Anthropology Annex B06E Albuquerque, New Mexico EDUCATION AND TRAINING University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM PhD Student 2019 – present Department of Anthropology Archaeology Subfield Fort Lewis College Durango, CO Visiting Instructor of Anthropology 2017 – 2019 Department of Anthropology University of York York, United Kingdom Master of Science, Bioarchaeology 2014 – 2016 Department of Archaeology Graduated with Merit Fort Lewis College Durango, CO Bachelor of Art, Anthropology 2009 – 2013 Department of Anthropology Graduated with Honors RESEARCH EXPERIENCE PhD Student 2019 - present University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM Advisors: Dr. Osbjorn Pearson, Dr Keith Prufer Rodents! Using stable isotopes to model dietary and environmental change from the Paleoindian period to the Mayan Collapse in modern Belize. – Currently studying the utility of using stable isotopes in rodent remains as a proxy for studying human dietary and environmental activity. Masters Student 2014 – 2016 University of York, York, United Kingdom Advisor: Dr. Matthew Collins Identifying potential sites of conflict through the analysis of possible human bone fragments via ZooMS (Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry). – Studied the applications of using ZooMS for the identification of human bone fragments in archaeological and forensic contexts. Nadia C. Neff | [email protected] | (970) 488 – 9932 1 – Combined traditional field survey and documentation methods with biomolecular protein analysis to create human bone scatter maps to identify possible sites of conflict. – Research based on a case study involving the Battle of Towton (1461) site. Collagen extraction method testing in highly degraded bone fragments – Tested collagen extraction methods (HCl demineralization versus AmBiC surface washing) on highly degraded bone fragments found in surface and top soil finds. -

Courage and Thoughtful Scholarship = Indigenous Archaeology Partnerships

FORUM COURAGE AND THOUGHTFUL SCHOLARSHIP = INDIGENOUS ARCHAEOLOGY PARTNERSHIPS Dale R. eroes Robert McGhee's recent lead-in American Antiquity article entitled Aboriginalism and Problems of Indigenous archaeology seems to emphasize the pitfalls that can occur in "indige nolls archaeology." Though the effort is l1ever easy, I would empha size an approach based on a 50/50 partnership between the archaeological scientist and the native people whose past we are attempting to study through our field alld research techniques. In northwestern North America, we have found this approach important in sharillg ownership of the scientist/tribal effort, and, equally important, in adding highly significant (scientif ically) cullUral knowledge ofTribal members through their ongoing cultural transmission-a concept basic to our explana tion in the field of archaeology and anthropology. Our work with ancient basketry and other wood and fiber artifacts from waterlogged Northwest Coast sites demonstrates millennia ofcultl/ral cOlltinuity, often including reg ionally distinctive, highly guarded cultural styles or techniques that tribal members continue to use. A 50/50 partnership means, and allows, joint ownership that can only expand the scientific description and the cultural explanation through an Indigenous archaeology approach. El artIculo reciente de Robert McGhee en la revista American Antiquity, titulado: Aborigenismo y los problemas de la Arque ologia Indigenista, pC/recen enfatizar las dificultades que pueden ocurrir en la "arqueologfa indigenista -

THE HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY of NATIVE AMERICANS Patricia E

P1: FBH August 28, 2000 9:45 Annual Reviews AR111-16 Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2000. 29:425–46 Copyright c 2000 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved THE HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY OF NATIVE AMERICANS Patricia E. Rubertone Department of Anthropology, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island 02912; e-mail: Patricia [email protected] Key Words acculturation, direct-historical approaches, landscapes, multicultural communities, colonialism ■ Abstract Historical archaeologists have given relatively scant attention to the study of Native Americans. Despite the potential to contribute to new understandings about Native peoples during and after European contact, the research commitment has been ambivalent at best. In this review, I ground this relationship in early debates about the field’s subject matter and concurrent discussions in anthropology about direct- historical and acculturation models. In addition, I highlight currents in research that have refined these approaches as well as those that have charted new directions. The latter are notable for helping comprehend the role of place and tradition in Native peoples’ lives, but also for reminding us of the complexities of identity construction in America after European contact. I reason that historical archaeology’s use of multiple sources, if linked creatively, can be crucial in producing knowledge about the past that illuminates the rich diversity of experiences among Native Americans. “Did these occurrences have a paradigm ... that went back in time? Or are we working out the minor details of a strictly random pattern?” Erdrich (1998:240) “...all of us remembering what we have heard together—that creates the whole story the long story of the people.” Silko (1981:7) INTRODUCTION Today, definitions of what constitutes historical archaeology are more broadly conceived than ever before. -

NHBSS 055 2E Fontaine Carb

Research articles NAT. NAT. HIST. BUL L. SIAM Soc. 55(2): 199 ・221 ,2∞7 CARBONIFEROUS CORALS OF PANG MAPHA DISTRICT , NORTHWEST THAILAND Henri Fontain eI and 拘 ravudh Suteethorn 2 ABSTRACT Abundant Abundant Carboniferous corals have been described in Central ηlailand (N oen Mapr 加 g to to Chon Daen area west of Phetchabun) and Northe ぉ tTh ailand (Loei and Nong Bua L 創 nphu 針。'vinces) (FONT Al NE EF AL. ,1991). 百 ey were previously unknown in Northwest Th ailand where where limestone exposures were ∞mmonly assigned to the Permian. Since then ,Carbonifer- ous ous fossils have been discovered at many limestone localities of Northwest Th ailand and corals corals have been collected mainly in Pang Mapha District (Dis 凶 ct established in 1997 with b 柏町is 岡山 n offices built ne 釘 Sop Pong Village). In fact ,Carboniferous limesto l) e is widespread 泊 Northwest Thailand and spans the whole Carboniferous (Fo 悶"A I阻 EF AL. , 1993). New and more detailed information on the corals is given in this paper. Corals Corals are common in the Lower Carboniferous limestones of Northwest Th ailand. 百ley consist consist mainly of Tabulata (Syringopora is widespread) and diverse solitary Rugosa (Ar ach- nolasma , Kueichouphyllum and others). Compound Rugosa locally occur and aI官 sporadicall y in in abundance. They consist of fascicula 飽 corals (Solenodendron ,D 伊'hyphyllum); massive Rugosa Rugosa have not been encountered up to now. At some localities , the corals are fragments accumulated accumulated by water currents. Elsewhe 陀,白ey are better preserved. Middle Carboniferous limestone containing so Ji tary Rugosa (Caninophyllum , Bothrophyllum 飢 d others) occurs at a few localities of Northwest Th ailand. -

COLIN RENFREW PAUL BAHN Theories, Methods, and Practice

COLIN RENFREW PAUL BAHN Theories, Methods, and Practice COLLEGE EDITION SEVENTH EDITION REVISED & UPDATED ~ Thames & Hudson CONTENTS Preface to the College Edition 9 BOX FEATURES Experimental Archaeology 53 Introduction Wet Preservation: The Ozette Site 60 The Nature and Aims of Archaeology 12 Dry Preservation: The Tomb of Tutankhamun 64 Cold Preservation 1: Mountain "Mummies" 67 Cold Preservation 2: Snow Patch Archaeology 68 PART I Cold Preservation 3: The Iceman 70 The Framework of Archaeology 19 3 Where? 1 The Searchers Survey and Excavation of Sites and Features 73 The History of Archaeology 21 Discovering Archaeological s.ites The Speculative Phase 22 and Features 74 The Beginnings of Modern Archaeology 26 Assessing the Layout of Sites and Features 98 Classification and Consolidation 32 Excavation 110 A Turning Point in Archaeology 40 Summary 130 World Archaeology 41 Further Reading 130 Summary 48 BOX FEATURES Further Reading 48 The Sydney Cyprus Survey Project 76 Sampling Strategies 79 BOX FEATURES Identifying Archaeological Features from Above 82 Digging Pompeii: Past and Present 24 Interpretation and Mapping From Aerial Images 86 Evolution: Darwin's Great Idea 27 Lasers in the Jungle 89 North American Archaeological Pioneers 30 GIS and the Giza Plateau 96 The Development of Field Techniques 33 Tell Ha lula: Multi-period Surface Investigations JOO Pioneering Women in Archaeology 38 Geophysical Survey at Roman Wroxeter 106 Processual Archaeology 41 Measuring Magnetism 108 Interpretive or Postprocessual Archaeologies 44 Underwater