Internally Displaced and Refugee Students in Cameroon: Some Pedagogical Proposals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

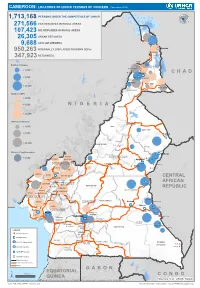

Page 1 C H a D N I G E R N I G E R I a G a B O N CENTRAL AFRICAN

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (November 2019) 1,713,168 PERSONS UNDER THE COMPETENCENIGER OF UNHCR 271,566 CAR REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 107,423 NIG REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 26,305 URBAN REFUGEES 9,688 ASYLUM SEEKERS 950,263 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPs) Kousseri LOGONE 347,923 RETURNEES ET CHARI Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees EXTRÊME-NORD MAYO SAVA < 3,000 Mora Mokolo Maroua CHAD > 5,000 Minawao DIAMARÉ MAYO TSANAGA MAYO KANI > 20,000 MAYO DANAY MAYO LOUTI Number of IDPs < 2,000 > 5,000 NIGERIA BÉNOUÉ > 20,000 Number of returnees NORD < 2,000 FARO MAYO REY > 5,000 Touboro > 20,000 FARO ET DÉO Beke chantier Ndip Beka VINA Number of asylum seekers Djohong DONGA < 5,000 ADAMAOUA Borgop MENCHUM MANTUNG Meiganga Ngam NORD-OUEST MAYO BANYO DJEREM Alhamdou MBÉRÉ BOYO Gbatoua BUI Kounde MEZAM MANYU MOMO NGO KETUNJIA CENTRAL Bamenda NOUN BAMBOUTOS AFRICAN LEBIALEM OUEST Gado Badzere MIFI MBAM ET KIM MENOUA KOUNG KHI REPUBLIC LOM ET DJEREM KOUPÉ HAUTS PLATEAUX NDIAN MANENGOUBA HAUT NKAM SUD-OUEST NDÉ Timangolo MOUNGO MBAM ET HAUTE SANAGA MEME Bertoua Mbombe Pana INOUBOU CENTRE Batouri NKAM Sandji Mbile Buéa LITTORAL KADEY Douala LEKIÉ MEFOU ET Lolo FAKO AFAMBA YAOUNDE Mbombate Yola SANAGA WOURI NYONG ET MARITIME MFOUMOU MFOUNDI NYONG EST Ngarissingo ET KÉLLÉ MEFOU ET HAUT NYONG AKONO Mboy LEGEND Refugee location NYONG ET SO’O Refugee Camp OCÉAN MVILA UNHCR Representation DJA ET LOBO BOUMBA Bela SUD ET NGOKO Libongo UNHCR Sub-Office VALLÉE DU NTEM UNHCR Field Office UNHCR Field Unit Region boundary Departement boundary Roads GABON EQUATORIAL 100 Km CONGO ± GUINEA The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA Source: IOM, OCHA, UNHCR – Novembre 2019 Pour plus d’information, veuillez contacter Jean Luc KRAMO ([email protected]). -

Mountain Resources Expliotation For

International Journal of Geography and Régional Planning Research Vol.1,No.1,pp.1-12, March 2014 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) MONTANE RESOURCES EXPLOITATION AND THE EMERGENCE OF GENDER ISSUES IN SANTA ECONOMY OF THE WESTERN BAMBOUTOS HIGHLANDS, CAMEROON Zephania Nji FOGWE Department of Geography, Box 3132, F.L.S.S., University of Douala ABSTRACT: Highlands have played key roles in the survival history of humankind. They are refuge heavens of valuable resources like fresh water endemic floral and faunal sanctuaries and other ecological imprints. The mountain resource base in most tropical Africa has been mined rather than managed for the benefit of the low-lying areas. The world over an appreciable population derives its sustenance directly from mountain resources and this makes for about one-tenth of the world’s poorest.The Western highlands of Cameroon are an archetypical territory of a high population density and an economically very active population. The highlands are characterised by an ecological fragility and a multi-faceted socio-economic dynamism at varied levels of poverty, malnutrition and under employment, yet about 80 percent of the Santa highlands’ population depends on its natural resource base of vast fertile land, fresh water and montane refuge forest for their livelihood. KEYWORDS: Montane Resources, Gender Issues, Santa Economy, Western Bamboutos, Cameroon INTRODUCTION The volcanic landscape on the western slopes of the Bamboutos mountain range slopes to the Santa Highlands is an area where agriculture in the form of crop production and animal rearing thrives with remarkable success. Arabica coffee cultivation was in extensive hectares cultivated at altitudes of about 1700m at the Santa Coffee Estate at Mile 12 in the 1970s and 1980s. -

Characterisation of Fungi of Stored Common Bean Cultivars Grown in Menoua Division, Cameroon

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.31.363184; this version posted November 1, 2020. The copyright holder has placed this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) in the Public Domain. It is no longer restricted by copyright. Anyone can legally share, reuse, remix, or adapt this material for any purpose without crediting the original authors. CHARACTERISATION OF FUNGI OF STORED COMMON BEAN CULTIVARS GROWN IN MENOUA DIVISION, CAMEROON TEH EXODUS AKWA*1, JOHN M MAINGI1, JONAH K. BIRGEN2 *Corresponding author: TEH EXODUS AKWA 1Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Biotechnology, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya 2Department of Plant Sciences, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya *Corresponding author: [email protected]; Tel.: +254 792 775729; Medical Microbiology, Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Biotechnology, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya, P.O BOX 43844-00100-NAIROBI 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.31.363184; this version posted November 1, 2020. The copyright holder has placed this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) in the Public Domain. It is no longer restricted by copyright. Anyone can legally share, reuse, remix, or adapt this material for any purpose without crediting the original authors. CHARACTERISATION OF FUNGI OF STORED COMMON BEAN CULTIVARS GROWN IN MENOUA DIVISION, CAMEROON. Abstract Common bean is a legume grown globally especially in developing countries including Cameroon for human consumption. In Cameroon it is grown in a wide variety of agro ecological zones in quantities enough to last through the off growing season after harvest. Stored common bean after harvest in Cameroon are prone to fungal spoilage which contributes to post harvest losses. -

Full Text Article

SJIF Impact Factor: 3.458 WORLD JOURNAL OF ADVANCE ISSN: 2457-0400 Alvine et al. PageVolume: 1 of 3.21 HEALTHCARE RESEARCH Issue: 4. Page N. 07-21 Year: 2019 Original Article www.wjahr.com ASSESSING THE QUALITY OF LIFE IN TOOTHLESS ADULTS IN NDÉ DIVISION (WEST-CAMEROON) Alvine Tchabong1, Anselme Michel Yawat Djogang2,3*, Michael Ashu Agbor1, Serge Honoré Tchoukoua1,2,3, Jean-Paul Sekele Isouradi-Bourley4 and Hubert Ntumba Mulumba4 1School of Pharmacy, Higher Institute of Health Sciences, Université des Montagnes; Bangangté, Cameroon. 2School of Pharmacy, Higher Institute of Health Sciences, Université des Montagnes; Bangangté, Cameroon. 3Laboratory of Microbiology, Université des Montagnes Teaching Hospital; Bangangté, Cameroon. 4Service of Prosthodontics and Orthodontics, Department of Dental Medicine, University of Kinshasa, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Received date: 29 April 2019 Revised date: 19 May 2019 Accepted date: 09 June 2019 *Corresponding author: Anselme Michel Yawat Djogang School of Pharmacy, Higher Institute of Health Sciences, Université des Montagnes; Bangangté, Cameroon ABSTRACT Oral health is essential for the general condition and quality of life. Loss of oral function may be due to tooth loss, which can affect the quality of life of an individual. The aim of our study was to evaluate the quality of life in toothless adults in Ndé division. A total of 1054 edentulous subjects (partial, mixed, total) completed the OHIP-14 questionnaire, used for assessing the quality of life in edentulous patients. Males (63%), were more dominant and the ages of the patients ranged between 18 to 120 years old. Caries (71.6%), were the leading cause of tooth loss followed by poor oral hygiene (63.15%) and the consequence being the loss of aesthetics at 56.6%. -

Assessment Report

Needs Assessment for Self-Reliance of CAR refugees in Gado, Borgop, Ngam, Mbile, Lolo and Timangolo Camps, and In Touboro Assessment Report Monitoring & Evaluation department November-December 2017 Page 1 of 30 Contents List of abbreviations ...................................................................................................................................... 3 List of figures ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Key findings/executive summary .................................................................................................................. 5 Operational Context ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction: The CAR situation In Cameroon .............................................................................................. 7 Objectives ..................................................................................................................................................... 8 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 9 Study Design ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Qualitative Approach ........................................................................................................................... -

Aerial Surveys of Wildlife and Human Activity Across the Bouba N'djida

Aerial Surveys of Wildlife and Human Activity Across the Bouba N’djida - Sena Oura - Benoue - Faro Landscape Northern Cameroon and Southwestern Chad April - May 2015 Paul Elkan, Roger Fotso, Chris Hamley, Soqui Mendiguetti, Paul Bour, Vailia Nguertou Alexandre, Iyah Ndjidda Emmanuel, Mbamba Jean Paul, Emmanuel Vounserbo, Etienne Bemadjim, Hensel Fopa Kueteyem and Kenmoe Georges Aime Wildlife Conservation Society Ministry of Forests and Wildlife (MINFOF) L'Ecole de Faune de Garoua Funded by the Great Elephant Census Paul G. Allen Foundation and WCS SUMMARY The Bouba N’djida - Sena Oura - Benoue - Faro Landscape is located in north Cameroon and extends into southwest Chad. It consists of Bouba N’djida, Sena Oura, Benoue and Faro National Parks, in addition to 25 safari hunting zones. Along with Zakouma NP in Chad and Waza NP in the Far North of Cameroon, the landscape represents one of the most important areas for savanna elephant conservation remaining in Central Africa. Aerial wildlife surveys in the landscape were first undertaken in 1977 by Van Lavieren and Esser (1979) focusing only on Bouba N’djida NP. They documented a population of 232 elephants in the park. After a long period with no systematic aerial surveys across the area, Omondi et al (2008) produced a minimum count of 525 elephants for the entire landscape. This included 450 that were counted in Bouba N’djida NP and its adjacent safari hunting zones. The survey also documented a high richness and abundance of other large mammals in the Bouba N’djida NP area, and to the southeast of Faro NP. In the period since 2010, a number of large-scale elephant poaching incidents have taken place in Bouba N’djida NP. -

Breaking Boko Haram and Ramping up Recovery: US-Lake Chad Region 2013-2016

From Pariah to Partner: The US Integrated Reform Mission in Burma, 2009 to 2015 Breaking Boko Haram and Ramping Up Recovery Making Peace Possible US Engagement in the Lake Chad Region 2301 Constitution Avenue NW 2013 to 2016 Washington, DC 20037 202.457.1700 Beth Ellen Cole, Alexa Courtney, www.USIP.org Making Peace Possible Erica Kaster, and Noah Sheinbaum @usip 2 Looking for Justice ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This case study is the product of an extensive nine- month study that included a detailed literature review, stakeholder consultations in and outside of government, workshops, and a senior validation session. The project team is humbled by the commitment and sacrifices made by the men and women who serve the United States and its interests at home and abroad in some of the most challenging environments imaginable, furthering the national security objectives discussed herein. This project owes a significant debt of gratitude to all those who contributed to the case study process by recommending literature, participating in workshops, sharing reflections in interviews, and offering feedback on drafts of this docu- ment. The stories and lessons described in this document are dedicated to them. Thank you to the leadership of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) and its Center for Applied Conflict Transformation for supporting this study. Special thanks also to the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of Transition Initiatives (USAID/OTI) for assisting with the production of various maps and graphics within this report. Any errors or omis- sions are the responsibility of the authors alone. ABOUT THE AUTHORS This case study was produced by a team led by Beth ABOUT THE INSTITUTE Ellen Cole, special adviser for violent extremism, conflict, and fragility at USIP, with Alexa Courtney, Erica Kaster, The United States Institute of Peace is an independent, nonpartisan and Noah Sheinbaum of Frontier Design Group. -

Migration, Migrants and Child Poverty

Migration, migrants and child poverty Although international migration has always been a feature of national life, this aspect of population change has increased over the last twenty years, mostly as a result of asylum seekers arriving in the 1990s and, more recently, migration from the new member states of the European Union (EU). While many migrant families have a reasonable income and a few are very prosperous, migrant children are disproportionally represented among children living in poverty. Many of the causes of child poverty for migrants are similar to those facing the UK-born population, but there are some factors that are specific to migrant households, such as language barriers and the severing of support networks. Here, Jill Rutter examines the link between child poverty and migration in the UK. Who are migrants? In the last five years, there has also been a sig- The United Nations’ definition of migrants are nificant onward migration of migrant communi- people who are resident outside their country of ties from other EU countries. Significant numbers birth. Many migrants in the UK have British citi- of Somalis, Nigerians, Ghanaians, Sri Lankan zenship, have been resident in the UK for many Tamils and Latin Americans have moved to the years and are more usually described as mem- UK from other EU countries. While many have bers of minority ethnic communities. This article secured citizenship or refugee status elsewhere uses the term ‘foreign born’ to describe those in the EU, some are irregular migrants. Most will outside their country of birth, and uses the term have received their education outside the EU ‘new migrants’ in a qualitative sense to describe and may have different qualifications and prior those new to the UK. -

Migrant and Displaced Children in the Age of COVID-19

Vol. X, Number 2, April–June 2020 32 MIGRATION POLICY PRACTICE Migrant and displaced children in the age of COVID-19: How the pandemic is impacting them and what can we do to help Danzhen You, Naomi Lindt, Rose Allen, Claus Hansen, Jan Beise and Saskia Blume1 vailable data and statistics show that children middle-income countries where health systems have have been largely spared the direct health been overwhelmed and under capacity for protracted effects of COVID-19. But the indirect impacts periods of time. It is in these settings where the next A surge of COVID-19 is expected, following China, Europe – including enormous socioeconomic challenges – are potentially catastrophic for children. Weakened and the United States.3 In low- and middle-income health systems and disrupted health services, job countries, migrant and displaced children often and income losses, interrupted access to school, and live in deprived urban areas or slums, overcrowded travel and movement restrictions bear directly on camps, settlements, makeshift shelters or reception the well-being of children and young people. Those centres, where they lack adequate access to health whose lives are already marked by insecurity will be services, clean water and sanitation.4 Social distancing affected even more seriously. and washing hands with soap and water are not an option. A UNICEF study in Somalia, Ethiopia and the Migrant and displaced children are among the most Sudan showed that almost 4 in 10 children and young vulnerable populations on the globe. In 2019, around people on the move do not have access to facilities to 33 million children were living outside of their country properly wash themselves.5 In addition, many migrant of birth, including many who were forcibly displaced and displaced children face challenges in accessing across borders. -

Cameroon July 2019

FACTSHEET Cameroon July 2019 Cameroon currently has On 25 July, UNHCR organized a A US Congress delegation 1,548,652 people of concern, preparatory workshop in visited UNHCR in Yaoundé on 01 including 287,467 Central Bertoua ahead of cross-border July and had an exchange with African and 107,840 Nigerian meeting on voluntary refugees and humanitarian actors refugees. repatriation of CAR refugees. on situation in the country. POPULATION OF CONCERN (1,548,652 AS OF 30 JULY) CAR REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 266,810 NIG REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 105,923 URBAN REFUGEES** 25,938 ASYLUM SEEKERS*** 8,972 IDPs FAR NORTH**** 262,831 IDPs NORTH-WEST/SOUTH-WEST***** 530,806 RETURNEES**** 347,372 **Incl. 20,657 Central Africans and 1,917 Nigerian refugees living in urban areas. ***Incl. 6,917 Central Africans and 42 Nigerian asylum seekers living in urban areas. **** Source: IOM DTM #18. Including 237,349 estimated returnees in NW/SW regions. *****IDPs in Littoral, North-West, South-West and West regions, Source: OCHA. FUNDING (AS OF 30 JULY) USD 90.3 M Requested for Cameroon Gap: 86% Gap: 74% UNHCR PRESENCE Staff: 251 167 National Staff 42 International Staff 42 Affiliate workforce (8 International and 34 National) 11 OFFICES: Representation – Yaounde Sub Offices – Bertoua, Meiganga, Maroua, Buea Field Offices – Batouri, Djohong, Touboro, Douala and Bamenda. Field Unit – Kousseri Refugees from Cameroon and UNHCR staff on a training visit to Songhai Farming Complex, Porto Novo-Benin www.unhcr.org 1 FACTSHEET > Cameroon – July 2019 WORKING WITH PARTNERS UNHCR coordinates protection and assistance for persons of concern in collaboration with: Government Partners: Ministries of External Relations, Territorial Administration, Economy, Planning and Regional Development, Public Health, Women’s Empowerment and the Family, Social Affairs, Justice, Basic Education, Water and Energy, Youth and Civic Education, the National Employment Fund and others, Secrétariat Technique des Organes de Gestion du Statut des réfugiés. -

Assessing Cost Efficiency Among Small Scale Rice Producers in the West Region of Cameroon: a Stochastic Frontier Model Approach

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) Volume 3, Issue 6, June 2016, PP 1-7 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2349-0381.0306001 www.arcjournals.org Assessing Cost Efficiency among Small Scale Rice Producers in the West Region of Cameroon: A Stochastic Frontier Model Approach Djomo, Raoul Fani*1, Ewung, Bethel1, Egbeadumah, Maryanne Odufa2 1Department of Agricultural Economics. University of Agriculture, Makurdi. Benue-State, Nigeria PMB 2373, Makurdi 2Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, Federal University Wukari, PMB 1020 Wukari. Taraba State, Nigeria *[email protected] Abstract: Local farmers’ techniques and knowledge in rice cultivation being deficient and the aid system and research to support such farmers’ activities likewise insufficient, technological progress and increase in rice production are not yet assured. Therefore, this Study was undertaken to assess cost efficiency among small scale rice farmers in the West Region of Cameroon using stochastic frontier model approach. A purposive, multistage and stratified random sampling technique was used in selecting the respondents. A total of 192 small scale rice farmers were purposively selected from four (4) out of eight divisions. Data were collected using structured questionnaires and interview schedule, administered on the respondents were analyzed using descriptive statistics and stochastic frontier cost functions. The result indicates that the coefficient of cost of labour was found positive and significantly influence cost of production in small scale rice production at 1 percent level of probability, implying that increases in cost of labour by one unit will also increase cost of production in small scale rice farming by the value of it coefficient. -

N I G E R I a C H a D Central African Republic Congo

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (September 2020) ! PERSONNES RELEVANT DE Maïné-Soroa !Magaria LA COMPETENCE DU HCR (POCs) Geidam 1,951,731 Gashua ! ! CAR REFUGEES ING CurAi MEROON 306,113 ! LOGONE NIG REFUGEES IN CAMEROON ET CHARI !Hadejia 116,409 Jakusko ! U R B A N R E F U G E E S (CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AND 27,173 NIGERIAN REFUGEE LIVING IN URBAN AREA ARE INCLUDED) Kousseri N'Djamena !Kano ASYLUM SEEKERS 9,332 Damaturu Maiduguri Potiskum 1,032,942 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSO! NS (IDPs) * RETURNEES * Waza 484,036 Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees MAYO SAVA Mora ! < 10,000 EXTRÊME-NORD Mokolo DIAMARÉ Biu < 50,000 ! Maroua ! Minawao MAYO Bauchi TSANAGA Yagoua ! Gom! be Mubi ! MAYO KANI !Deba MAYO DANAY < 75000 Kaele MAYO LOUTI !Jos Guider Number! of IDPs N I G E R I A Lafia !Ləre ! < 10,000 ! Yola < 50,000 ! BÉNOUÉ C H A D Jalingo > 75000 ! NORD Moundou Number of returnees ! !Lafia Poli Tchollire < 10,000 ! FARO MAYO REY < 50,000 Wukari ! ! Touboro !Makurdi Beke Chantier > 75000 FARO ET DÉO Tingere ! Beka Paoua Number of asylum seekers Ndip VINA < 10,000 Bocaranga ! ! Borgop Djohong Banyo ADAMAOUA Kounde NORD-OUEST Nkambe Ngam MENCHUM DJEREM Meiganga DONGA MANTUNG MAYO BANYO Tibati Gbatoua Wum BOYO MBÉRÉ Alhamdou !Bozoum Fundong Kumbo BUI CENTRAL Mbengwi MEZAM Ndop MOMO AFRICAN NGO Bamenda KETUNJIA OUEST MANYU Foumban REPUBLBICaoro BAMBOUTOS ! LEBIALEM Gado Mbouda NOUN Yoko Mamfe Dschang MIFI Bandjoun MBAM ET KIM LOM ET DJEREM Baham MENOUA KOUNG KHI KOUPÉ Bafang MANENGOUBA Bangangte Bangem HAUT NKAM Calabar NDÉ SUD-OUEST