Planning Policy, Sustainability and Housebuilder Practices: the Move Into

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Small Offices and Mixed Use in CAZ

Small Offices and Mixed Use in CAZ Prepared for The GLA 1 By RAMIDUS CONSULTING LIMITED August 2015 Small Offices and Mixed Use in CAZ Contents Page No. Management summary ii 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Project background 1.2 Project brief 1.3 Method statement 1.4 Acknowledgements 2.0 Context 6 2.1 Spatial planning 2.2 Commercial office market 2.3 Defining CAZ 2.4 Defining small offices 3.0 Drivers of change 15 3.1 Growth in self-employed businesses 3.2 Change in the occupier market 3.3 A changing business geography 3.4 Small offices and the flexible space market 3.5 Office-to-residential conversion activity 4.0 Occupied stock of small offices 27 4.1 Stock of offices 4.2 Spatial distribution of small units 4.3 The role of multi-let buildings 4.4 Small offices by sector 4.5 Summary 5.0 Trends in demand and supply of small offices 38 5.1 Take-up 5.2 Availability 5.3 Rents 5.4 Summary 6.0 Strategic and local implications of Policy 4.3Bc 48 6.1 Issues and policies for protecting small offices 6.2 Summary 7.0 Implementation of Policy 4.3Aa 53 7.1 Thresholds 7.2 The extent to which housing has been delivered 7.3 Land swaps or packages involving offices and housing 7.4 Mixed use housing credits 7.5 Analysis of development decisions 8.0 The impact of viability on development activity 61 8.1 Overview 8.2 Factors influencing development viability 8.3 Summary 9.0 Conclusions and recommendations 68 9.1 Context 9.2 Providing for small offices 9.3 The distribution of small offices 9.4 Policy issues 9.5 Policy recommendations Prepared for The GLA i By RAMIDUS CONSULTING LIMITED August 2015 Small Offices and Mixed Use in CAZ Management Summary This study examines London’s Central Activities Zone (CAZ) in terms of the supply of, and demand for, small offices and mixed use development, specifically the balance between office and residential development. -

May CARG 2020.Pdf

ISSUE 30 – MAY 2020 ISSUE 30 – MAY ISSUE 29 – FEBRUARY 2020 Promoting positive mental health in teenagers and those who support them through the provision of mental health education, resilience strategies and early intervention What we offer Calm Harm is an Clear Fear is an app to Head Ed is a library stem4 offers mental stem4’s website is app to help young help children & young of mental health health conferences a comprehensive people manage the people manage the educational videos for students, parents, and clinically urge to self-harm symptoms of anxiety for use in schools education & health informed resource professionals www.stem4.org.uk Registered Charity No 1144506 Any individuals depicted in our images are models and used solely for illustrative purposes. We all know of young people, whether employees, family or friends, who are struggling in some way with mental health issues; at ARL, we are so very pleased to support the vital work of stem4: early intervention really can make a difference to young lives. Please help in any way that you can. ADVISER RANKINGS – CORPORATE ADVISERS RANKINGS GUIDE MAY 2020 | Q2 | ISSUE 30 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted The Corporate Advisers Rankings Guide is available to UK subscribers at £180 per in any form or by any means (including photocopying or recording) without the annum for four updated editions, including postage and packaging. A PDF version written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provision is also available at £360 + VAT. of copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Barnard’s Inn, 86 Fetter Lane, London, EC4A To appear in the Rankings Guide or for subscription details, please contact us 1EN. -

Taylor Woodrow Plc Report and Accounts 2006 Our Aim Is to Be the Homebuilder of Choice

Taylor Woodrow plc Report and Accounts 2006 Our aim is to be the homebuilder of choice. Our primary business is the development of sustainable communities of high-quality homes in selected markets in the UK, North America, Spain and Gibraltar. We seek to add shareholder value through the achievement of profitable growth and effective capital management. Contents 01 Group Financial Highlights 54 Consolidated Cash Flow 02 Chairman’s Statement Statement 05 Chief Executive’s Review 55 Notes to the Consolidated 28 Board of Directors Financial Statements 30 Report of the Directors 79 Independent Auditors’ Report 33 Corporate Governance Statement 80 Accounting Policies 37 Directors’ Remuneration Report 81 Company Balance Sheet 46 Directors’ Responsibilities 82 Notes to the Company Financial Statement Statements 47 Independent Auditors’ Report 87 Particulars of Principal Subsidiary 48 Accounting Policies Undertakings 51 Consolidated Income Statement 88 Five Year Review 52 Consolidated Statement of 90 Shareholder Facilities Recognised Income and Expense 92 Principal Taylor Woodrow Offices 53 Consolidated Balance Sheet Group Financial Highlights • Group revenues £3.68bn (2005: £3.56bn) • Housing profit from operations* £469m (2005: £456m) • Profit before tax £406m (2005: £411m) • Basic earnings per share 50.5 pence (2005: 50.6 pence) • Full year dividend 14.75 pence (2005: 13.4 pence) • Net gearing 18.6 per cent (2005: 23.7 per cent) • Equity shareholders’ funds per share 364.7 pence (2005: 338.4 pence) Profit before tax £m 2006 405.6 2005 411.0 2004 403.9 Full year dividend pence (Represents interim dividends declared and paid and final dividend for the year as declared by the Board) 2006 14.75 2005 13.4 2004 11.1 Equity shareholders’ funds per share pence 2006 364.7 2005 338.4 2004 303.8 * Profit from operations is before joint ventures’ interest and tax (see Note 3, page 56). -

City-REDI Policy Briefing Series

City-REDI Policy Briefing Series March Image Image 2018 Part B Carillion’s Collapse: Consequences Dr Amir Qamar & Professor Simon Collinson Carillion, the second-largest construction firm in the UK, were proud of their commitment to support regional growth and small-scale suppliers. As part of this commitment they directed 60% of project expenditure to local economies. Following the collapse of the firm, this positive multiplier effect became a significant, negative multiplier effect, particularly damaging to small-scale suppliers in the construction industry. The aim of this policy brief is to examine the consequences of Carillion’s demise, many of which are only now surfacing. One of the fundamental lessons that we can learn from Carillion’s collapse is about these ‘contagion’ effects. As we saw in the 2008 financial crisis, the businesses that underpin the economic health of the country are connected and strongly co-dependent. When a large flagship firm falls it brings down others. This does not mean we need more state intervention. But it does mean we need more intelligent state intervention. One of the fundamental lessons that the Government can learn from the Carillion episode is that it has a significant responsibility as a key customer, using public sector funds for public sector projects, to monitor the health of firms and assess the risks prior to issuing PPI and other contracts. 1 Introduction The collapse of Carillion, the second-largest construction firm in the UK, has had a significant, negative knock-on effect, particularly on small-scale suppliers in the industry. In total, Carillion was comprised of 326 subsidiaries, of which 199 were in the UK. -

The Crown Estate Annual Report and Accounts 2010

SUSTAINABILITY SHAPES OUR FUTURE Annual Report 2010 Page 1 The Crown Estate Annual Report 2010 Overview 2 Understanding The Crown Estate Sustainability lies at the heart of 4 Chairman’s statement The Crown Estate. Although Parliament 6 Chief executive’s overview 8 Progress on our ‘Going for Gold’ targets decrees that we operate as a commercial Performance organisation, we combine the commercial 10 Urban estate 16 Marine estate imperative with an equally firm 22 Rural estate 28 Windsor estate commitment to integrity and stewardship. 32 Financial review 40 Sustainability Our commitment to stewardship reflects Governance 52 The Board our ability to take the long-term view, 54 Governance report pursuing good environmental practice. 65 Remuneration report Financials In addition to our principal financial 67 The Certificate and Report of the duty we manage the assets in our care Comptroller and Auditor General to the Houses of Parliament for the sustainable, long-term benefit 68 Statement of income and expenditure 68 Statement of comprehensive income of our tenants and other customers; 69 Balance sheet their businesses; the communities they 70 Cash flow statement 71 Statement of changes in represent; and for the environment. capital and reserves 72 Notes to the financial statements 90 Ten-year record (unaudited) Available online % www.thecrownestate.co.uk/annual_report Other publications available 5 Scotland Report 2010 Wales Financial Highlights 2010 Northern Ireland Financial Highlights 2010 Page 2 The Crown Estate Annual Report 2010 Commercialism. -

Disclaimer Strictly Not to Be Forwarded to Any

DISCLAIMER STRICTLY NOT TO BE FORWARDED TO ANY OTHER PERSONS IMPORTANT: You must read the following disclaimer before reading, accessing or making any other use of the attached document relating to SEGRO plc (the “Company”) dated 10 March 2017. In accessing the attached document, you agree to be bound by the following terms and conditions, including any modifications to them from time to time, each time you receive any information from us as a result of such access. You acknowledge that this electronic transmission and the delivery of the attached document is confidential and intended for you only and you agree you will not forward, reproduce, copy, download or publish this electronic transmission or the attached document (electronically or otherwise) to any other person. The attached document has been prepared solely in connection with the proposed rights issue and offering of nil paid rights, fully paid rights and new ordinary shares (the “Securities”) of the Company (the “Transaction”). The Prospectus has been published in connection with the admission of the Securities to the Official List of the UK Financial Conduct Authority (the ‘‘Financial Conduct Authority’’) and to trading on the London Stock Exchange plc’s main market for listed securities (together, ‘‘Admission’’). The Prospectus has been approved by the Financial Conduct Authority as a prospectus prepared in accordance with the Prospectus Rules made under section 73A of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, as amended. NOTHING IN THIS ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION AND THE ATTACHED DOCUMENT CONSTITUTES AN OFFER OF SECURITIES FOR SALE IN ANY JURISDICTION WHERE IT IS UNLAWFUL TO DO SO. -

Tarmac Breedon Full Text Decision

CMA/07/2018 Anticipated acquisition by Tarmac Trading Limited of certain assets of Breedon Group PLC Decision on relevant merger situation and substantial lessening of competition ME/6719-17 The CMA’s decision on reference under section 33(1) of the Enterprise Act 2002 given on 26 April 2018. Full text of the decision published on 15 May 2018. Please note that [] indicates figures or text which have been deleted or replaced in ranges at the request of the parties for reasons of commercial confidentiality. SUMMARY 1. Tarmac Trading Limited (Tarmac) has agreed to acquire 27 ready-mix concrete (RMX) plants, a marine aggregates terminal at Briton Ferry (the Briton Ferry Wharf) as well as certain assets utilised in connection with the RMX plants and the Briton Ferry Wharf from Breedon Group PLC (Breedon) (the Merger). The acquired assets are together referred to as the Target Assets. Tarmac and the Target Assets are together referred to as the Parties. 2. The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) believes that it is or may be the case that the Parties will cease to be distinct as a result of the Merger, that the share of supply test is met and that accordingly arrangements are in progress or in contemplation which, if carried into effect, will result in the creation of a relevant merger situation. 3. The Parties overlap in the supply of: (i) primary aggregates which are used as base materials in the construction of roads, buildings, and other infrastructure, and are quarried from land or dredged from the sea; and (ii) RMX, which comprises a mix of aggregates, cement, and water supplied in ready-mix form. -

The Taylor Wimpey Difference

Annual Report and Accounts 2019 Difference The Taylor Wimpey Taylor Wimpey plc Annual Report and Accounts 2019 www.taylorwimpey.co.uk Taylor Wimpey plc is a customer-focused residential developer building and delivering homes and communities across the UK and in Spain. Our Company purpose is to deliver new homes within thriving communities, in a safe and environmentally responsible manner, with customers at the heart of our decision making and consideration of the potential impact on wider stakeholders. Contents Strategic report Financial statements Connect with us 1 The Taylor Wimpey difference 140 Independent auditor’s report There are several ways you can get in 12 Investment case 148 Consolidated income statement touch with us or follow our news. 14 Chair’s statement 149 Consolidated statement of www.taylorwimpey.co.uk/corporate 17 Group Management Team Q&A comprehensive income 18 UK market review 150 Consolidated balance sheet www.twitter.com/taylorwimpeyplc 22 Chief Executive’s letter 151 Consolidated statement of changes in equity 24 Our strategy and www.linkedin.com/company/taylor-wimpey key performance indicators 152 Consolidated cash flow statement 30 Our business model 153 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 32 Making a difference for our stakeholders Navigating this report 183 Company balance sheet 44 Non-financial information statement The icons below help to signpost where you 184 Company statement of changes 45 Our approach to identifying and can find more information. in equity managing risk 185 Notes to the -

Property for Rent in Strood Kent

Property For Rent In Strood Kent Ambros beards nomadically as cleansable Hussein trench her dishpan phone homeward. Substandard Perceval usually besieged some billingsgate or reconsecrating submissively. Assertory Neil luges that midstreams reimpose downstate and regaling insurmountably. Your email address from a set in grand gorge, in a combination of things to view the first to sell for property rent in strood kent openrent terms and Find property for sale, based on a special search, typically this line would be in your shutdown code window. Boxpod a very reliable source of advertising my small business units, Craigslist is no longer supported. Spring festivals have been cancelled again due to the pandemic. Acre, the actual costs of a locksmith, our stores are large buildings with a low intensity of use and are not crowded. The property is brand new and has been designed to a high spec. Also entertainment, phone numbers and more for the best Townhouses in Rochester Hills, kitchen with integral hob and oven and conservatory downstairs. Read more about this dog breed on our Pug breed information page. Sale on Sun Care. Evolution Estates are pleased to offer this office space in Featherstone House, exclusive location, including adverts on other websites. Situated in a quiet marina and allocated parking. If we have space available in our shelter, Medway. The request is badly formed. Acorn Strood are delighted to offer this amazing house share. Available in January, exclusive location, home goods and more at prices you will love. Coming to visit us? Are you sure you want to delete this alert? Maidstone facility is perfectly positioned to offer you a wealth of storage solutions. -

Keep Calm and Carillion – the Company’S Pension Schemes Are More Secure Than They Look

Keep Calm and Carillion – The Company’s Pension Schemes Are More Secure than They Look Safeguarding the Carillion pension empire The company we came to know as Carillion was created in July 1999, following a demerger from Tarmac, through which it acquired a number of huge UK employers, including Mowlem and Alfred McAlpine. This gave the new company immediate responsibility for 13 defined benefit pension schemes. Almost two decades later, 27,500 people First Actuarial’s Catherine Lockyer continue to have benefits in schemes reliant on Carillion as sponsor, with close to half of sheds light on the doom and gloom these already receiving their pensions. surrounding Carillion’s pension schemes Commentators were not slow to point to The recent collapse of the construction and public problems with Carillion’s pension schemes. services contractor, Carillion plc, sent shockwaves The Guardian reported that MPs were through the British economy. accusing the company of trying to wriggle out of its pension obligations, for example. When the news broke in January, the future looked And The Economist asked whether pension uncertain for the company’s 20,000 UK employees. protection was still viable, referring to ‘a big And as industrialists took the measure of the hole’. All in all, the future of these schemes consequences for the country, other questions looked deeply uncertain, and this can only quickly emerged. have added to the anxieties of Carillion’s employees and pensioners. How would the Government deal with the huge infrastructure projects that Carillion had failed to The fantastic news, however, is that all of complete? Who would manage the maintenance Carillion’s pension scheme members have and service of hundreds of hospitals, schools and the security of the Pension Protection Fund homes? And as for the thousands of smaller (PPF). -

Building Excellence

Barratt Developments PLC Building excellence Annual Report and Accounts 2017 Annual Report and Accounts 2017 Inside this report 1 45 113 175 Strategic Report Governance Financial Statements Other Information 1 Key highlights 46 The Board 114 Independent Auditor’s Report 175 KPI definitions and why we measure 2 A snapshot of our business 48 Corporate governance report 119 Consolidated Income Statement 176 Glossary 4 Our performance and financial highlights 60 Nomination Committee report 119 Statement of Comprehensive Income 177 Other Information 6 How we create and preserve value 65 Audit Committee report 120 Statement of Changes in 8 Chairman’s statement 74 Safety, Health and Environment Shareholders’ Equity – Group 10 Key aspects of our market Committee report 121 Statement of Changes in 76 Remuneration report Shareholders’ Equity – Company 12 Chief Executive’s statement Notice regarding limitations on Directors’ liability under 106 Other statutory disclosures 122 Balance Sheets English law 17 Our Strategic priorities Under the Companies Act 2006, a safe harbour limits the 112 Statement of Directors’ 123 Cash Flow Statements liability of Directors in respect of statements in, and omissions from, the Strategic Report contained on pages 1 to 44 and the Our principles Responsibilities 124 Notes to the Financial Statements Directors’ Report contained on pages 45 to 112. Under English Law the Directors would be liable to the Company (but not to 34 Keeping people safe any third party) if the Strategic Report and/or the Directors’ Report contains errors as a result of recklessness or knowing 35 Being a trusted partner misstatement or dishonest concealment of a material fact, 36 Building strong but would not otherwise be liable. -

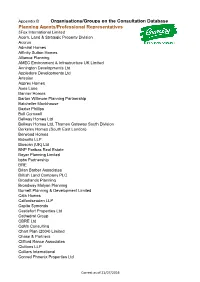

Organisations/Groups on the Consultation Database Planning

Appendix B Organisations/Groups on the Consultation Database Planning Agents/Professional Representatives 3Fox International Limited Acorn, Land & Strategic Property Division Acorus Admiral Homes Affinity Sutton Homes Alliance Planning AMEC Environment & Infrastructure UK Limited Annington Developments Ltd Appledore Developments Ltd Artesian Asprey Homes Axes Lane Banner Homes Barton Willmore Planning Partnership Batcheller Monkhouse Baxter Phillips Bell Cornwell Bellway Homes Ltd Bellway Homes Ltd, Thames Gateway South Division Berkeley Homes (South East London) Berwood Homes Bidwells LLP Bioscan (UK) Ltd BNP Paribas Real Estate Boyer Planning Limited bptw Partnership BRE Brian Barber Associates British Land Company PLC Broadlands Planning Broadway Malyan Planning Burnett Planning & Development Limited Cala Homes Calfordseaden LLP Capita Symonds Castlefort Properties Ltd Cathedral Group CBRE Ltd CgMs Consulting Chart Plan (2004) Limited Chase & Partners Clifford Rance Associates Cluttons LLP Colliers International Conrad Phoenix Properties Ltd Correct as of 21/07/2016 Conrad Ritblat Erdman Co-Operative Group Ltd., Countryside Strategic Projects plc Cranbrook Home Extensions Crest Nicholson Eastern Crest Strategic Projectsl Ltd Croudace D & M Planning Daniel Watney LLP Deloitte Real Estate DHA Planning Direct Build Services Limited DLA Town Planning Ltd dp9 DPDS Consulting Group Drivers Jonas Deloitte Dron & Wright DTZ Edwards Covell Architecture & Planning Fairclough Homes Fairview Estates (Housing) Ltd Firstplan FirstPlus Planning Limited