Download a Pdf of This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lourdes Pilgrimage Pius XII

University of Dayton eCommons Marian Reprints Marian Library Publications 1958 055 - The Lourdes Pilgrimage Pius XII Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_reprints Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Pius, XII, "055 - The Lourdes Pilgrimage" (1958). Marian Reprints. Paper 61. http://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_reprints/61 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Reprints by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ?alye'araf ENCYCTICAL LETTER OF PIUS XII Number 55 ABOUT THE DOCUMENT O ' ' In the present encyclical The Lourdes Pitgri,mage, His Holiness Pope Pius XII recalls the apparitions of Our Lady to St. Berna- dette Soubirous at Lourdes, reviews the relationship the Popes, since Pius IX have had with the famous shrine, encourages pil- grimages during the present Lourdes Year of 1958, and points out a special lesson to be learned from a contemplation of the message of Lourdes-an awareness of the supernatural in our lives so that we may guard against the materialism which is threatening to overcome the modern world. OUTLINE OF THE ENCYCLICAL Introduction: Reasons for Writing the Encyclical I. Past History of Lourdes 1. Marian Devotion in France 2. The Miraculous Medal 3. The Apparitions at Lourdes 4. The Popes and Lourdes a. Pius IX and Leo XIII b. Pius X c. Benedict XV and Pius XI d. Pius XII II. The Grace of Lourdes 1. Individual Conversion a. -

Chapter 5 Art Offers a Glimpse at a Different World Than That Which The

chapter 5 Art Art offers a glimpse at a different world than that which the written narratives of early Rome provide. Although the producers (or rather, the patrons) of both types of work may fall into the same class, the educated elite, the audience of the two is not the same. Written histories and antiquarian works were pro- duced for the consumption of the educated; monuments, provided that they were public, were to be viewed by all. The narrative changes required by dyadic rivalry are rarely depicted through visual language.1 This absence suggests that the visual narratives had a different purpose than written accounts. To avoid confusion between dyadic rivals and other types of doubles, I con- fine myself to depictions of known stories, which in practice limits my inves- tigation to Romulus and Remus.2 Most artistic material depicting the twins comes from the Augustan era, and is more complimentary than the literary narratives. In this chapter, I examine mainly public imagery, commissioned by the same elite who read the histories of the city. As a result, there can be no question of ignorance of this narrative trope; however, Roman monuments are aimed at a different and wider audience. They stress the miraculous salvation of the twins, rather than their later adventures. The pictorial language of the Republic was more interested in the promo- tion of the city and its elite members than problematizing their competition. The differentiation between artistic versions produced for an external audi- ence and the written narratives for an internal audience is similar to the dis- tinction made in Propertius between the inhabitants’ knowledge of the Parilia and the archaizing gloss shown to visitors. -

Pope Benedict XVI's Invitation Joseph Mele

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 2008 Homiletics at the Threshold: Pope Benedict XVI's Invitation Joseph Mele Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Mele, J. (2008). Homiletics at the Threshold: Pope Benedict XVI's Invitation (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/919 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOMILETICS AT THE THRESHOLD: POPE BENEDICT XVI‘S INVITATION A Dissertation Submitted to The McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Joseph M. Mele May 2008 Copyright by Joseph M. Mele 2008 HOMILETICS AT THE THRESHOLD: POPE BENEDICT XVI‘S INVITATION By Joseph M. Mele Approved Month Day, 2008 ____________________________ ____________________________ Name of Professor Name of Professor Professor of Professor of (Dissertation Director) (Committee Member) ____________________________ ____________________________ Name of Professor Name of Professor Professor of Professor of (Committee Member) (Committee Member) ___________________________ ____________________________ Name of Dean Name of External Reviewer Dean, The McAnulty -

Observing Protest from a Place

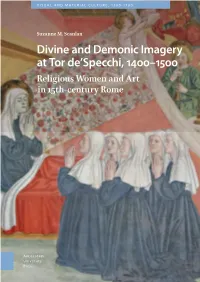

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

Integrating Ecology and Justice: the New Papal Encyclical by Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim

Feature Integrating Ecology and Justice: The New Papal Encyclical by Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim Mat McDermott Una Terra Una Famiglia Humana, One Earth One Family climate march in Vatican City in June 2015. In Brief In June of 2015, Pope Francis released the first encyclical on ecology. The Pope’s message highlights “integral ecology,” intrinsically linking ecological integrity and social justice. While the encyclical notes the statements of prior Popes and Bishops on the environment, Pope Francis has departed from earlier biblical language describing the domination of nature. Instead, he expresses a broader understanding of the beauty and complexity of nature, on which humans fundamentally depend. With “integral ecology” he underscores this connection of humans to the natural environment. This perspective shifts the climate debate to one of a human change of consciousness and conscience. As such, the encyclical has the potential to bring about a tipping point in the global community regarding the climate debate, not merely among Christians, but to all those attending to this moral call to action. 38 | Solutions | July-August 2015 | www.thesolutionsjournal.org n June 18, 2015 Pope Francis thinking. By drawing on and develop- We can compare Pope Francis’ released Laudato Si, the first ing the work of earlier theologians and thinking to the writing of Pope John encyclical in the history of ethicists, this encyclical makes explicit Paul II, who himself builds on Pope O Rerum the Catholic Church on ecology. An the links between social justice and Leo XIII’s progressive encyclical encyclical is the highest-level teaching eco-justice.1 Novarum on workers’ rights in 1891. -

CONDEMNATION of COMMUNISM in PONTIFICAL MAGISTERIUM Since Pius IX Till Paul VI

CONDEMNATION OF COMMUNISM IN PONTIFICAL MAGISTERIUM since Pius IX till Paul VI Petru CIOBANU Abstract: The present article, based on several magisterial documents, illus- trates the approach of Roman Pontiffs, beginning with Pius IX and ending with Paul VI, with regard to what used to be called „red plague”, i.e. communism. The article analyses one by one various encyclical letters, apostolic letters, speeches and radio messages in which Roman Pontiffs condemned socialist theories, either explicitly or implicitly. Keywords: Magisterium, Pope, communism, socialism, marxism, Christianity, encyclical letter, apostolic letter, collectivism, atheism, materialism. Introduction And there appeared another wonder in heaven; and behold a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads. And his tail drew the third part of the stars of heaven, and did cast them to the earth: and the dragon stood before the woman which was ready to be delivered, for to devour her child as soon as it was born. And when the dragon saw that he was cast unto the earth, he persecuted the woman which brought forth the man child. And the dragon was wroth with the woman, and went to make war with the remnant of her seed, which keep the commandments of God, and have the testimony of Jesus Christ (Rev 12,3-4.13.17). These words, written over 2.000 years ago, didn’t lose their value along time, since then and till now, reflecting the destiny of Christian Church and Christians – „those who guard the God words and have the Jesus tes- timony” – in the world, where appear so many „dragons” that have the aim to persecute Jesus Christ followers. -

THE CORE THEMES of the ENCYCLICAL FRATELLI TUTTI St

THE CORE THEMES OF THE ENCYCLICAL FRATELLI TUTTI St. John Lateran, 15 November 2020 Card. GIANFRANCO RAVASI Preamble Let us begin from a spiritual account drawn from Tibetan Buddhism, a different world from that of the encyclical, but significant nonetheless. A man walks alone on a desert track that dissolves into the distance on the horizon. He suddenly realises that there is another being, difficult to make out, on the same path. It may be a beast that inhabits these deserted spaces; the traveller’s heart beats faster and faster out of fear, as the wilderness does not offer any shelter or help, so he must continue to walk. As he advances, he discerns the profile: a man’s. However, fear does not leave him; in fact, that man could be a fierce bandit. He has no choice but to go on, as the fear of an assault grips his soul. The traveller no longer has the courage to look up. He can hear the other man’s steps approaching. The two men are now face to face: he looks up and stares at the person before him. In his surprise he cries out: “This is my brother whom I haven’t seen for many years!” We wish to refer to this ancient parable from a different religion and culture at the beginning of this presentation to show that the yearning pervading Pope Francis’s new encyclical Fratelli tutti is an essential component of the spiritual breadth of all humanity. In fact, we find a few unexpected “secular” quotations in the text, such as the 1962 album Samba da Bênção by Brazilian poet and musician Vinicius de Moraes (1913-1980) in which he sang: “Life, for all its confrontations, is the art of encounter” (n. -

Kenneth A. Merique Genealogical and Historical Collection BOOK NO

Kenneth A. Merique Genealogical and Historical Collection SUBJECT OR SUB-HEADING OF SOURCE OF BOOK NO. DATE TITLE OF DOCUMENT DOCUMENT DOCUMENT BG no date Merique Family Documents Prayer Cards, Poem by Christopher Merique Ken Merique Family BG 10-Jan-1981 Polish Genealogical Society sets Jan 17 program Genealogical Reflections Lark Lemanski Merique Polish Daily News BG 15-Jan-1981 Merique speaks on genealogy Jan 17 2pm Explorers Room Detroit Public Library Grosse Pointe News BG 12-Feb-1981 How One Man Traced His Ancestry Kenneth Merique's mission for 23 years NE Detroiter HW Herald BG 16-Apr-1982 One the Macomb Scene Polish Queen Miss Polish Festival 1982 contest Macomb Daily BG no date Publications on Parental Responsibilities of Raising Children Responsibilities of a Sunday School E.T.T.A. BG 1976 1981 General Outline of the New Testament Rulers of Palestine during Jesus Life, Times Acts Moody Bible Inst. Chicago BG 15-29 May 1982 In Memory of Assumption Grotto Church 150th Anniversary Pilgrimage to Italy Joannes Paulus PP II BG Spring 1985 Edmund Szoka Memorial Card unknown BG no date Copy of Genesis 3.21 - 4.6 Adam Eve Cain Abel Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 4.7- 4.25 First Civilization Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 4.26 - 5.30 Family of Seth Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 5.31 - 6.14 Flood Cainites Sethites antediluvian civilization Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 9.8 - 10.2 Noah, Shem, Ham, Japheth, Ham father of Canaan Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 10.3 - 11.3 Sons of Gomer, Sons of Javan, Sons -

The Appropriation of Valois Style by a Converso Contador Mayor 121

1196 69. Sanchis Sivera, ‘La escultura valenciana’, p. 22. 70. Peter Kovâc, ‘Notes on the Description of the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris from 1378’, in Fajt (ed.), Court Chapels, pp. 162-70, here, p. 163; Meredith Cohen, The Sainte-Chapelle and the Construction of Sacral Monarchy (Cambridge-New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), pp. 159-64. 71. For Vincennes, see Odette Chapelot et al., ‘Un chantier et son maître d’oeuvre: Raymond du Temple et la Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes’, in Odette Chapelot (ed.), Du projet au chantier. Maîtres d’ouvrage et maîtres d’oeuvre aux XIVe- XVIe siècles (Paris: École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, 2001), pp. 433-88. For its relationship with the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris and successive imitations in Aachen and Westmins- ter, see Dany Sandron, ‘La culture des architectes de la fin du Moyen Âge. À propos de Raymond du Temple à la Sainte-Cha- pelle de Vincennes’, Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 150: 2 (2006): pp. 1255-79, esp. pp. 1260-79. Connections between decorative sculpture in late fourteenth-century France and the Crown of Aragon have been observed by Maria Rosa Terés in ‘La escultura del Gótico Internacional en la Corona de Aragón: los primeros años (c. 1400-1416)’, Artigrama 26 (2011): pp. 147-81. Inventio and 72. García Marsilla, ‘El poder visible’, pp. 39-40; first mentioned in the sources in 1426: Rafael Beltrán Llavador, ‘Los orígenes del Grial en las leyendas artúricas. Interpretaciones cristianas y visiones simbólicas’, Tirant: Butlletí informatiu i bibliogràfic 11 (2008): pp. -

John Allen Jr. Emerges As America's Premier

20 Contents Established in 1902 as The Graduate Magazine FEATURES ‘The Best Beat in Journalism’ 20 How a high school teacher from Hays became America’s top Vatican watcher. BY CHRIS LAZZARINO Happy Together 32 Can families who are truly gifted at being families teach the rest of us how to fashion happier homes? COVER Psychologist Barbara Kerr thinks so. Where the BY STEVEN HILL 24 Music Moves In only three years the Wakarusa Music and Camping Festival has grown from a regional upstart to a national star on the summer rock circuit. BY CHRIS LAZZARINO Cover photo illustration by Susan Younger 32 V olume 104, No. 4, 2006 Lift the Chorus NEW! Hail Harry toured China during the heyday of “pingpong diplomacy,” cur- JAYHAWK Thank you for the arti- rently celebrating its 35th cle on economics anniversary. JEWELRY Professor Harry Shaffer KU afforded many such [“Wild about Harry,” rewarding cosmopolitan experi- Oread Encore, issue No. ences for this western Kansas 3]. As I read the story, I student to meet and learn to fondly recalled taking his know others from distant cul- class over 20 years ago. tures. Why, indeed, can’t we all One fascinating item neg- learn to get along? lected in the article was how Harry Marty Grogan, e’68, g’71 ended up at KU. Seattle Originally a professor at the University of Alabama, he left in disgust Cheers to the engineers when desegregation was denied at the institution. This was a huge loss to The letter from Virginia Treece Crane This new KU Crystal set shimmers Alabama, but an incredible gift to those [“Cool house on Memory Lane,” issue w ith a delicate spark le. -

Theological Quarterl~

THEOLOGICAL QUARTERL~ . ... /;/ ,.:) .,...., ,' ·"'.,. VOL. XIII. OCTOBER, 1909. No. 4. THE MURDEROUS POPE: Lord, keep us in Thy Word and work; Restrain the murderous Pope and Turk! Luther.. Christ bids preach the Gospel; He does not bid us force_ the Gospel on any. He argued and showed from the Scripture that He was the Savior, e. g., on the way to Emmaus. When the . Samaritans would not receive Christ, James and John asked, "Lord, wilt Thou that we command fire to come down from heaven, and consume them?" But the Savior rebuked them, "Ye know not what manner of spirit ye are of. For the Son of Man is not come to destroy men's lives, but to save them," Luke 9, 52-5(l, Christ said to Peter, "Put up thy sword!" Christ assured Pontius Pilate, "My kingdom is not of this ',vorld." . The Apostle says: "Not that we have dominion over your faith, but are helpers of your joy," 2 Cor. 1, 24; 1 Pet. 5, 8. "We persuade men," 2 Cor: 5, 11-20; 1 Cor. 9, 19-22; · Eph. 3, 14-19. "Prove all things; hold fast that which is good," 1 Thess. 5, 21. "I speak unto wise men; judge ye what I say," 1 Cor. 10, 15; Acts 17, 11. 12. "We do not war after the flesh; for, the· weapons of our warfare are not carnal," 2 Cor. 10, 4. Athanasius pronounced it a mark of the true religion that it forced no one and declared persecution an invention and a . mark of Satan. Chrysostom said that to kill heretics was to 18 194 THE MURDEROUS POPI~. -

"De Actibus Alfonsi Di Cartagena": Biography and the Craft of Dying In

DE A CTIBUS ALFONSI DE CARTA GENA : BIOGRAPHY AND THE CRAFT OF DYING IN FIFTEENTH-CENTURY CASTILE Jeremy Lawrance University of Manchester I, Manuscript trudiitun. authorship, and date De act thus Alfonsi de Cartagena episcopi Purgens is is known to scholars as a source on the life of Alfonso García de Santamaria, later called Alfonso de Cartagena. a leading figure in the ecclesiastical and literary history of fifteenth-century Castile In this paper 1 approach the text from a different perspective, attempting a literary study of the work together with critical edition, translation, and commentary. De actibus is preserved in two fifteenth-century witnesses, M (Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional, MS 7432. fols 89-92) and /■ (Fermo. Biblioteca Comunalc. MS 77, fols 54r-60) A further witness, now- lost, is listed in Father Sigüenza’s sixteenth-century catalogue of the Escorial library Alfonsi de Cartagena libri Genealogiae Regum His panic cum tractaiu quodam inccrti autlioris de ciusdcm Alfonsi uita et References to De achbus arc io hnc-mimbcrs in my edition below The "ork is used by Manuel Martinez Anibatro > Rixes. Intento de un diccionario biográfico y bihfiogrtifico de autores de ¡a provincia de Hurgas (.Madrid. Manuel Tello. 1889), pp 88-115; Luciano Serrano, conversos D Pabto de Sama Maria y I). Alfonso de Cartagena obispos de Purgas, gobernantes, diplomáticos y escritores (Madrid CSlC. 1942). pp 119-260. and Francisco Cantera Burgos. J/ror (jarcia tie Santa Mario i su familia de conversas: historia de la judería de Purgas > de uá Conversos más egregios (.Madrid CS1C. 1952). pp. 416-64 The text was fj rsl edited by Yolanda Espinosa Fernández.