Foreign Policy Think Tanks: Challenging Or Building Consensus on India’S Pakistan Policy?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 43 Electoral Statistics

CHAPTER 43 ELECTORAL STATISTICS 43.1 India is a constitutional democracy with a parliamentary system of government, and at the heart of the system is a commitment to hold regular, free and fair elections. These elections determine the composition of the Government, the membership of the two houses of parliament, the state and union territory legislative assemblies, and the Presidency and vice-presidency. Elections are conducted according to the constitutional provisions, supplemented by laws made by Parliament. The major laws are Representation of the People Act, 1950, which mainly deals with the preparation and revision of electoral rolls, the Representation of the People Act, 1951 which deals, in detail, with all aspects of conduct of elections and post election disputes. 43.2 The Election Commission of India is an autonomous, quasi-judiciary constitutional body of India. Its mission is to conduct free and fair elections in India. It was established on 25 January, 1950 under Article 324 of the Constitution of India. Since establishment of Election Commission of India, free and fair elections have been held at regular intervals as per the principles enshrined in the Constitution, Electoral Laws and System. The Constitution of India has vested in the Election Commission of India the superintendence, direction and control of the entire process for conduct of elections to Parliament and Legislature of every State and to the offices of President and Vice- President of India. The Election Commission is headed by the Chief Election Commissioner and other Election Commissioners. There was just one Chief Election Commissioner till October, 1989. In 1989, two Election Commissioners were appointed, but were removed again in January 1990. -

Asia in the Contemporary World

WPF Historic Publication Asia in the Contemporary World Inder Kumar Gujral December 31, 2004 Original copyright © 2004 by World Public Forum Dialogue of Civilizations Copyright © 2016 by Dialogue of Civilizations Research Institute The right of Inder Kumar Gujral to be identified as the author of this publication is hereby asserted. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the original author(s) and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views and opinions of the Dialogue of Civilizations Research Institute, its co-founders, or its staff members. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, please write to the publisher: Dialogue of Civilizations Research Institute gGmbH Französische Straße 23 10117 Berlin Germany +49 30 209677900 [email protected] Asia in the Contemporary World Inder Kumar Gujral Former Prime Minister of India Originally published 2004 in World Public Forum Dialogue of Civilizations Bulletin 1(1), 158–64. 2 Inder Kumar Gujral “Asia in the contemporary world” Surely I am voicing the feelings of my fellow participants when I thank the three zealously committed foundations for hosting this Conference at a time when the world is confronted with massive challenges of instability and a gravely damaged U.N. system. Not long back, on first day of the new millennium, the world leaders had gathered to re-affirm their faith in the “purpose and principles of the charter of the United Nations, which have proved timeless and universal. -

The Northern Areas, Pakistan's Forgotten Colony in Jammu And

IJGR 11,1-2_ f7-186-228 7/28/04 7:17 AM Page 187 International Journal on Minority and Group Rights 11: 187–228, 2004. 187 © Koninklijke Brill NV. Printed in the Netherlands. Of Rivers and Human Rights: The Northern Areas, Pakistan’s Forgotten Colony in Jammu and Kashmir ANITA D. RAMAN* Following armed hostilities in 1947–1949 between India and Pakistan and inter- vention by the international community, the region once known as the Princely State of Jammu & Kashmir was divided. Commencing no later than October 1947, the Kashmir dispute has proved the most protracted territorial dispute in the United Nations era. Since the termination of hostilities and the signing of the Karachi Agreement of August 1949 between India and Pakistan, approximately one third of the former Princely State has been under the de facto control of Pakistan. The Northern Areas constitute the majority of Pakistan-controlled Kashmir, and little is known regarding internal governance in the region. Despite its long- held position that the entirety of the former Princely State is disputed territory, the Federation of Pakistan has recently commenced steps to incorporate the region as the ‘fifth province’ of Pakistan. Section I of this note outlines the his- tory of the use of force in and occupation of the former Princely State, focusing on the internal administrative setup of the region following 1948. Section II looks to the concept of nationhood in order to assess whether the residents of the Northern Areas are a people within the meaning of international law on the right of self-determination and proposes a possible way forward in the assessment of the will of the peoples of the region. -

Part 05.Indd

PART MISCELLANEOUS 5 TOPICS Awards and Honours Y NATIONAL AWARDS NATIONAL COMMUNAL Mohd. Hanif Khan Shastri and the HARMONY AWARDS 2009 Center for Human Rights and Social (announced in January 2010) Welfare, Rajasthan MOORTI DEVI AWARD Union law Minister Verrappa Moily KOYA NATIONAL JOURNALISM A G Noorani and NDTV Group AWARD 2009 Editor Barkha Dutt. LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI Sunil Mittal AWARD 2009 KALINGA PRIZE (UNESCO’S) Renowned scientist Yash Pal jointly with Prof Trinh Xuan Thuan of Vietnam RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL GAIL (India) for the large scale QUALITY AWARD manufacturing industries category OLOF PLAME PRIZE 2009 Carsten Jensen NAYUDAMMA AWARD 2009 V. K. Saraswat MALCOLM ADISESHIAH Dr C.P. Chandrasekhar of Centre AWARD 2009 for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. INDU SHARMA KATHA SAMMAN Mr Mohan Rana and Mr Bhagwan AWARD 2009 Dass Morwal PHALKE RATAN AWARD 2009 Actor Manoj Kumar SHANTI SWARUP BHATNAGAR Charusita Chakravarti – IIT Delhi, AWARDS 2008-2009 Santosh G. Honavar – L.V. Prasad Eye Institute; S.K. Satheesh –Indian Institute of Science; Amitabh Joshi and Bhaskar Shah – Biological Science; Giridhar Madras and Jayant Ramaswamy Harsita – Eengineering Science; R. Gopakumar and A. Dhar- Physical Science; Narayanswamy Jayraman – Chemical Science, and Verapally Suresh – Mathematical Science. NATIONAL MINORITY RIGHTS MM Tirmizi, advocate – Gujarat AWARD 2009 High Court 55th Filmfare Awards Best Actor (Male) Amitabh Bachchan–Paa; (Female) Vidya Balan–Paa Best Film 3 Idiots; Best Director Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots; Best Story Abhijat Joshi, Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Male) Boman Irani–3 Idiots; (Female) Kalki Koechlin–Dev D Best Screenplay Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Abhijat Joshi–3 Idiots; Best Choreography Bosco-Caesar–Chor Bazaari Love Aaj Kal Best Dialogue Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra–3 idiots Best Cinematography Rajeev Rai–Dev D Life- time Achievement Award Shashi Kapoor–Khayyam R D Burman Music Award Amit Tivedi. -

India Now 6Th Worst-Hit Nation by COVID-19, Surpasses Italy

VP, PM, Najma, CM 25 new cases detected in last 24 hours to take tally to 157 condole Marwah ......... India now 6th worst-hit Nation by N DELHI/IMP, Jun 6 : Vice President M Venkaiah Naidu With Pherzawl joining list, COVID-19 spreads to all dists and Prime Minister Narendra By Our Staff Reporter opened a helpline number COVID-19, surpasses Italy Modi condoled the demise of for frontline workers such as Marwah, recalling his "unwa- IMPHAL, Jun 6: Following doctors, nurses, paramedics, NEW DELHI, Jun 6 vering courage" which stood detection of three positive truck/bus drivers, police, India went past Italy to Nagaland COVID-19 count crosses out during his career. cases in Pherzawl district, not media, sanitation workers become the sixth worst-hit a single district of Manipur is and volunteers. 100, fourth in NE to hit century mark "Shri Ved Marwah Ji will Nation by the COVID-19 now free from COVID-19. They can contact mental be remembered for his rich pandemic with the country GUWAHATI , Jun 6 During the last 24 hours, health professionals on mo- contributions to public life. registering a record single- the State recorded 25 bile number 9402751364. His unwavering courage al- day spike of 9,887 cases Nagaland has become the fourth North Eastern State after COVID-19 positive cases. On the other hand, the in- ways stood out during his which pushed the Nationwide Assam, Tripura and Manipur to have more than 100 COVID- According to a press re- creasing number of career as an IPS officer," tally to 2,36,657. -

Annual Report 2014

VweJssm&Mcla 9nie^m U cm al ^h u yixia tlfm Annual Report 2014 G w d m ti Preface About VIF Our Relationship Worldwide Activities Seminars & Interactions . International Relations & Diplomacy . National Security & Strategic Studies . Neighbourhood Studies . Economic Studies . Historical & Civilisational Studies Reaching Out . Vimarsha . Scholars' Outreach Resource Research Centre and Library Publications VIF Website & E-Journal Team VIF Advisory Board & Executive Council Finances P ^ e la c e Winds of Change in India 2014 was a momentous year for India that marked the end of coalition governments and brought in a Government with single party majority after 40 years with hopes of good governance and development. Resultantly, perceptions and sentiments about India also improved rapidly on the international front. Prime Minister Modi’s invite to SAARC heads of states for his swearing in signified his earnestness and commitment to enhancing relationships with the neighbours. Thereafter, his visits to Bhutan, Japan, meeting President Xi Jinping and later addressing the UN and summit with President Obama underlined the thrust of India’s reinvigoration of its foreign and security policies. BRICS, ASEAN and G-20 summits were the multilateral forums where India was seen in a new light because of its massive political mandate and strength of the new leadership which was likely to hasten India’s progress. Bilateral meets with Myanmar and Australian leadership on the sidelines of ASEAN and G-20 and visit of the Vietnamese Prime Minister to India underscored PM Modi’s emphasis on converting India’s Look East Policy to Act East Policy’. International Dynamics While Indian economy was being viewed with dismay in the first half of the year, now India is fast becoming an important and much sought after destination for investment as the change of government has engendered positive resonance both at home and abroad. -

22 September (2019)

Weekly Current Affairs (English) 16 September – 22 September (2019) Weekly Current Affairs (English) National News 1. Kiren Rijuju flags off 'Great Ganga Run' marathon to create awareness about Ganga Union Minister for Youth Affairs and Sports, Kiren Rijiju along with Union Minister for Jal Shakti, Gajendra Singh Shekhawat flagged off "Great Ganga Run" at Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium. The marathon was organised to create awareness about 'Ganga'. "It is a good initiative by Ministry of Jal Shakti. This marathon has been organised by them. It has a very elaborative message. Ganga is very important for the country and we needed to create awareness. In this marathon, people from every age group are participating. I would like to congratulate the organisers on getting a number of people involved with Namami Gange Marathon," Rijiju told reporters. Foot Notes: 1. Jal Shakti Minister: Gajendra Singh Shekhawat. 2. Minister of State (Independent Charge) of Youth Affairs and Sports: Kiren Rijiju. 2. Rajasthan Government launches Jan Soochna Portal 2019 The first-ever public information portal launched in Rajasthan promising to provide information about government authorities and departments suo motu to the public in the true spirit of the Right To Information Act. The portal has brought yet another distinction to Rajasthan, where the RTI movement started in 1990s. Chief Minister Ashok Gehlot inaugurated the portal at B.M. Birla Auditorium in the presence of former Chief Information Commissioner Wajahat Habibullah, former Law Commission chairman Justice A.P. Shah and a galaxy of RTI activists, including Magsaysay Award winner Aruna Roy. The State government collaborated with the civil society groups to develop the portal, the first of its kind in the country, initially giving information pertaining to 13 departments on a single platform. -

Current Affairs of January 2020 Quick Point

Studentsdisha.in Current Affairs of January 2020 Quick Point Content SI No. Topic Page Number 1 Important Day & Date with Theme 2-3 2 Important Appointments 3-5 3 Awards and Honours 5-21 Crossword Books Awards 7 Ramnath Goenka Excellence Awards 7-8 Pradhan Mantri Rashtriya Bal Puraskar 2020 8 National Bravery Award 2019 8-9 Padma Awards 2020 9-14 Jeevan Raksha Padak Award 2020 14-16 62nd Grammy Awards 2020 16-20 77th Golden Globe Award 2020 20-21 4 Sports 21-24 ICC Annual Award 2019 21-22 Australian Open 2020 22 5 BOOKS & Authors 24 6 Summit & Conference 24-25 7 Ranking and Index 25-26 8 MoU Between Countries 26 9 OBITUARIES 26-27 10 National & International News 28-35 1 Studentsdisha.in January 2020 Quick Point Important Day & Date with Theme of January 2020 Day Observation/Theme 1st Jan Global Family Day World Peace Day 4th Jan World Braille Day 6th Jan Journalists’ Day in Maharashtra 6th Jan The World Day of War Orphans 7th Jan Infant Protection Day 8th Jan African National Congress Foundation Day 9th Jan Pravasi Bharatiya Divas/NRI Day( 16th edition) 10thJan “World Hindi Day” 10thJan World Laughter Day 12th Jan National Youth Day or Yuva Diwas. Theme:"Channelizing Youth Power for Nation Building". 14th Jan Indian Armed Forces Veterans Day 15thJan Indian Army Day(72nd) 16thJan Religious Freedom day 18th Jan 15th Raising Day of NDRF(National Disaster Response Force) 19th Jan National Immunization Day (NID) 21st Jan Tripura, Manipur &Meghalaya 48th statehood day 23rdJan Subhash Chandra Bose Jayanti 24th to 30th National Girl Child Week Jan 24thJan National Girl Child Day Theme:‘Empowering Girls for a Brighter Tomorrow’. -

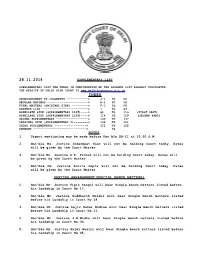

Notes Seating Arrangement(Special Bench

28.11.2014 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR TODAY IN CONTINUATION OF THE ADVANCE LIST ALREADY CIRCULATED. THE WEBSITE OF DELHI HIGH COURT IS www.delhihighcourt.nic.in INDEX PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGMENTS ------------> J-1 TO 02 REGULAR MATTERS -----------------------> R-1 TO 52 FINAL MATTERS (ORIGINAL SIDE) ---------> F-1 TO 06 ADVANCE LIST --------------------------> 1 TO 84 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> 85 TO 113 (FIRST PART) APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> 114 TO 129 (SECOND PART) SECOND SUPPLEMENTARY ------------------> 130 TO 137 ORIGINAL SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY I)--------> 138 TO 151 THIRD SUPPLEMENTARY ------------------> 152 TO 152 COMPANY ------------------------------> TO NOTES 1. Urgent mentioning may be made before Hon'ble DB-II at 10.30 A.M. 2. Hon'ble Ms. Justice Indermeet Kaur will not be holding Court today. Dates will be given by the Court Master. 3. Hon'ble Mr. Justice A.K. Pathak will not be holding Court today. Dates will be given by the Court Master. 4. Hon'ble Ms. Justice Sunita Gupta will not be holding Court today. Dates will be given by the Court Master. SEATING ARRANGEMENT(SPECIAL BENCH MATTERS) 1. Hon'ble Mr. Justice Vipin Sanghi will hear Single bench matters listed before his Lordship in Court No.17. 2. Hon'ble Mr. Justice Siddharth Mridul will hear Single bench matters listed before his Lordship in Court No.18. 3. Hon'ble Mr. Justice Rajiv Sahai Endlaw will hear Single bench matters listed before his Lordship in Court No.33. 4. Hon'ble Mr. Justice J.R.Midha will hear Single bench matters listed before his Lordship in Court No.36. -

A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan

The Role of Geography in Human Security: A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan PhD Thesis Submitted by Ehsan Mehmood Khan, PhD Scholar Regn. No. NDU-PCS/PhD-13/F-017 Supervisor Dr Muhammad Khan Department of Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) Faculties of Contemporary Studies (FCS) National Defence University (NDU) Islamabad 2017 ii The Role of Geography in Human Security: A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan PhD Thesis Submitted by Ehsan Mehmood Khan, PhD Scholar Regn. No. NDU-PCS/PhD-13/F-017 Supervisor Dr Muhammad Khan This Dissertation is submitted to National Defence University, Islamabad in fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Peace and Conflict Studies Department of Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) Faculties of Contemporary Studies (FCS) National Defence University (NDU) Islamabad 2017 iii Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for Doctor of Philosophy in Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) Department NATIONAL DEFENCE UNIVERSITY Islamabad- Pakistan 2017 iv CERTIFICATE OF COMPLETION It is certified that the dissertation titled “The Role of Geography in Human Security: A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan” written by Ehsan Mehmood Khan is based on original research and may be accepted towards the fulfilment of PhD Degree in Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS). ____________________ (Supervisor) ____________________ (External Examiner) Countersigned By ______________________ ____________________ (Controller of Examinations) (Head of the Department) v AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis titled “The Role of Geography in Human Security: A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan” is based on my own research work. Sources of information have been acknowledged and a reference list has been appended. -

Orm Lead T^^Pitalism? ^ * Tianjin Sewage Treatment Plant China's Largest Sewage Treatment Plant Was Completed Recently in Tianjin

w A CHINESE WEEKLY OF NEWS AND VIEWS February 3, 1986 Vol. 2^mr% orm Lead T^^pitalism? ^ * Tianjin Sewage Treatment Plant China's largest sewage treatment plant was completed recently in Tianjin. With an area of 30 hectares, and a waste capacity of 360,000 tons a day, the plant contains a water pump station, precipitation and aeration tanks and sludge digestion containers. Lab technicians testing the water at the Tianjin Sewage Treament Plant. Waste water treatment facilities in the sewage treatment plant. The methane gas produced in the process of treating sludge at the plant is used to generate electricity. A view of the Tianjin Sewage Treatment Plant. SPOTLIQHT VOL. 29, NO. 5 FEBRUARY 3, 1986 HIGHLIGHTS OF THE WEEK CONTENTS NOTES FROM THE EDITORS 4-5 Taiwan—Tugging at Chinese Formula for China's Reunification Heartstrings The "one country, two systems " concept, advocated by EVENTS/TRENI^ 6-10 the Chinese Party and government, proved successful in solving Zhao Outlines Tasks for '86 the Hongkong issue in 1984. After making a detailed analysis of Reform the common ground and conditions for the reunification of Steel Industry Sets Moderate Taiwan and the mainland, the author concluded that the Goal Taiwan issue, though different from that of Hongkong, can Education Made Compulsory also be settled by the "one country, two systems" method (p. Welfare Benelits 100 Million 18). Needy 100-Yr-OId Donates Body to Medicine Zliao Sets Goals for '86 Reform Obese Children Worries Doctors At a national conference on planning and economic work INTERNAT10MAL 1114 held in Beijing recently, Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang said United States: King's Dream Not China's major tasks for 1986 economic reform were to improve Yet Reality overall economic control, continue the current reforms already India-Pakistan: Neighbours Gett• in place and invigorate production. -

Annual Report 2018-2019

Seeking Harmony in Diversity Vivekananda International Foundation Annual Report | 2018-19 O Lord! Protect us together, nurture us together. May we work together. May our studies be illuminated. May we not have discord. May there be peace, peace and peace. (Katha Upanishad | Shanti Mantra) © Vivekananda International Foundation 2019 Published in June 2019 by Vivekananda International Foundation 3, San Martin Marg | Chanakyapuri | New Delhi - 110021 Tel: 011-24121764 | Fax: 011-66173415 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.vifindia.org Follow us on Twitter @vifindia | Facebook /vifindia Chairman’s Foreword ………………………………………………………………………………………...7 VIF Family ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………29-37 Trustees Advisory Council Executive Committee Team VIF Director’s Preface ……………………………………………………………………………………………….39 About the VIF ……………………………………………………………………………………………………..47 Outcomes …………………………………………………………………………………………………………...51 Publications ………………………………………………………………………………………………………...55 Activities ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………65 Seminars and Interactions ………………………………………………………………………………66-114 International Relations and Diplomacy National Security and Strategic Studies Neighbourhood Studies Historical and Civilisational Studies Governance and Political Studies Economic Studies Scientific and Technological Studies Outreach ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..115 Resource Research Centre and Library ……………………………………………………………..133 Our Exchanges Worldwide ………………….…………………………………………………………….135 Annual Report | 2018-19 | 5 Chairman’s Foreword