The Case of Powerboat Racing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Activities

Water Activities Kayaking Number of Participants 180 max per day Age/Swimming Ability From 8 years / 10 metres Ratio 1:10 Self-Run Possibility BC L2 Coach Timescale 1½–3 hours A challenging activity where pupils learn basic paddling techniques, teamwork and communication skills through a combination of games and instruction both on and off the water. Canoeing Number of Participants 40 max per day Age/Swimming Ability From 8 years / 10 metres Ratio 1:10 Self-Run Possibility BC L2 Coach Timescale 1½–3 hours These Open Canadian Canoes are much like the ones American Indians used to paddle. Each boat takes up to three paddlers and they are a great way to travel and see the lake and share the experience with friends. This activity can be used to gain BC awards and complete GCSE syllabuses (see page 8). Kata Kanu Number of Participants 40 max per day Age/Swimming Ability From 8 years / 10 metres Ratio 1:10 Self-Run Possibility BC L2 Coach (1:5 ratio) Timescale 1–2 hours Kata Kanu’s are similar to two Canadian Canoes rafted together. Each Kata Kanu can hold a maximum of five participants. These boats are extremely stable and are great fun. This is an excellent activity for special needs groups. tel 01895 824171 website www.hoac.net email [email protected] 11 Water Activities Please note: activities on pages 12–13 cannot be self-run. Bell Boating Number of Participants 40 max per day Age/Swimming Ability From 8 years / 10 metres Ratio 1:10 Timescale 1–2 hours* Bell boats are a fantastic way to introduce groups to watersports and encourage team work. -

Desert Storm on Scene at the Nation’S Hottest Event

BlowoutDesert Storm On Scene at the Nation’s Hottest Event MYSTIC PLEASURE BOAT EVOLUTION: THE INSIDE STORY OUTERLIMITS OFFSHORE POWERBOATS TURNS 20 DRIVING MISS GEICO << PAST, PRESENT & FUTURE ISSUE 2 JULY/AUGUST 2013 2 JULY/AUGUST ISSUE -VYWYP]H[LHWWVPU[TLU[Z! 3LHYUTVYLH[JPNHYL[[LYHJPUNJVT MIAMI・ CHICAGO・ SAVANNAH・ DALLAS・ ST. TROPEZ・ IBIZA・ KOLN・ ROME・ DUBAI・ DOHA・ MOSCOW・ HONG KONG・ ATHENS・ TOKYO START JULY/AUGUST 2013 | VOLUME 1 | ISSUE 2 | SPEEDONTHEWATER.COM FEATURES 24 34 42 48 What Drives Outerlimits’ The Appeal of Fifty Feet of Miss GEICO? 20th Anniversary Desert Storm Pure Pleasure Find out why the most Mike Fiore, owner of There are all kinds The performance of recognized team in Outerlimits Offshore of reasons why the Mystic’s first 50-foot offshore racing never Powerboats, reflects Desert Storm Poker catamaran with twin stops moving forward on two decades of Run attracts a variety Mercury Racing 1350 and what it takes to building high-end race of boats to Arizona’s engines matches the keep the ship afloat. and pleasure boats. scenic Lake Havasu. boat’s sheer beauty. From the Editors REGULARS 06 Having fun covering the best beat in the world Hot Sheet 08 Latest headlines from the world of go-fast boats Teague’s Take 12 Bob Teague breaks down propeller basics On Scene 16 Highlights from the Texas Outlaw Challenge Gear A closer look at the latest and greatest products Cover photo by Jay Nichols, Miss GEICO image Rodrick Cox 20 ON THE COVER Jon Roth and John Tomlinson drive Roth’s Skater Powerboats 388 SS at the Desert Storm Poker Run on Arizona’s Lake Havasu. -

An Economy Where Home and Automobile Sales Have Fallen Through the Floor, and Credit Is Tighter Than the Tolerances in an F1

an economy where home and automobile sales have fallen guy who might have stepped up in the past is looking at his through the floor, and credit is tighter than the tolerances in boat and saying, ‘I might be better served to put my $5000 an F1 engine, it should come as no surprise to anyone that or $10,000 back into this boat and let it last me two or three new performance boats are not exactly flying off of showroom more years.’ So that segment of our market is strong...and floors. However, this trend holds its share of opportunities for there’s still opportunity.” racing entrepreneurs. Drag Boat Racers Unite! “Boats are definitely a luxury item, and we are seeing signif- By all accounts, despite record fuel prices and the economic icant cutbacks in OEM orders,” said Tom Veronneau at Livorsi downturn, marine racing left a very decent 2008 season in its Marine in Grayslake, Illinois, a supplier of gauges, dash panels, wake...and is looking forward to more of the same in 2009. controls, headers, and other products for the marine, off-road, Several sanctioning organizations had big news to report. and auto racing markets. “I almost feel guilty saying this, but we’re going into our As a direct result of those slowed sales, Veronneau and biggest year ever,” enthused Charlie Fegan of the International others we spoke with in the performance marine industry Hot Boat Association (IHBA) in Bosque Farms, New Mexico, reported upbeat news for the aftermarket as enthusiasts refur- who told us that all US drag boat racing has been united under bish and upgrade their existing craft for an additional year or the Lucas Oil Drag Boat Racing Series for 2009. -

Drive Historic Southern Indiana

HOOSIER HISTORY STATE PARKS GREEK REVIVAL ARCHITECTURE FINE RESTAURANTS NATURE TRAILS AMUSEMENT PARKS MUSEUMS CASINO GAMING CIVIL WAR SITES HISTORIC MANSIONS FESTIVALS TRADITIONS FISHING ZOOS MEMORABILIA LABYRINTHS AUTO RACING CANDLE-DIPPING RIVERS WWII SHIPS EARLY NATIVE AMERICAN SITES HYDROPLANE RACING GREENWAYS BEACHES WATER SKIING HISTORIC SETTLEMENTS CATHEDRALS PRESIDENTIAL HOMES BOTANICAL GARDENS MILITARY ARTIFACTS GERMAN HERITAGE BED & BREAKFAST PARKS & RECREATION AZALEA GARDENS WATER PARKS WINERIES CAMP SITES SCULPTURE CAFES THEATRES AMISH VILLAGES CHAMPIONSHIP GOLF COURSES BOATING CAVES & CAVERNS Drive Historic PIONEER VILLAGES COVERED WOODEN BRIDGES HISTORIC FORTS LOCAL EVENTS CANOEING SHOPPING RAILWAY RIDES & DINING HIKING TRAILS ASTRONAUT MEMORIAL WILDLIFE REFUGES HERB FARMS ONE-ROOM SCHOOLS SNOW SKIING LAKES MOUNTAIN BIKING SOAP-MAKING MILLS Southern WATERWHEELS ROMANESQUE MONASTERIES RESORTS HORSEBACK RIDING SWISS HERITAGE FULL-SERVICE SPAS VICTORIAN TOWNS SANTA CLAUS EAGLE WATCHING BENEDICTINE MONASTERIES PRESIDENT LINCOLN’S HOME WORLD-CLASS THEME PARKS UNDERGROUND RIVERS COTTON MILLS Indiana LOCK & DAM SITES SNOW BOARDING AQUARIUMS MAMMOTH SKELETONS SCENIC OVERLOOKS STEAMBOAT MUSEUM ART EXHIBITIONS CRAFT FAIRS & DEMONSTRATIONS NATIONAL FORESTS GEMSTONE MINING HERITAGE CENTERS GHOST TOURS LECTURE SERIES SWIMMING LUXURIOUS HOTELS CLIMB ROCK WALLS INDOOR KART RACING ART DECO BUILDINGS WATERFALLS ZIP LINE ADVENTURES BASKETBALL MUSEUM PICNICKING UNDERGROUND RAILROAD SITE WINE FESTIVALS Historic Southern Indiana (HSI), a heritage-based -

The Clark Flyer October 2008

The Clark Flyer The official publication of the Clark County Radio Control Society. Volume 08, Issue 10, October, 2008 Editor: John Shirron [email protected] 2008 Club Officers The Clark Flyer President October 2008 Luis Munoz Well, I know it’s kraut; another oh so good! All and all, a [email protected] fall for two rea- very successful day was had by all at the sons. One, be- flying field. Vice President cause I just On another note, October, and November Dave Agar picked all the are nominations for club officers. All po- [email protected] gourds from my sitions are open for you to volunteer for, garden, and two, Secretary or to nominate someone for. If you want because I also Greg Agar to help the club by volunteering yourself just flew in our for a position, or know someone that [email protected] October Fest Fun Fly. There was a good would make a good nominee, just email Treasury turnout for the fun fly and fun was had by any of the officers or come to the No- all. The weather was perfect, a little cool Steve Piper vember meeting to make ideas know. It’s in the morning, and the sun in the after- [email protected] because of volunteers like you that make noon; perfect! I know that it was the first our club a fun and successfully group of Safety Director time I ever dropped a plastic Easter egg people to be a part of, along with provid- filled with flower and beans, and had it Ted Atmore ing the community with a good place to actually explode on impact; way cool. -

The Keystone State's Official Boating Magazine I

4., • The Keystone State's Official Boating Magazine i Too often a weekend outing turns to tragedy because a well- meaning father or friend decides to take "all the kids" for a boat ride, or several fishing buddies go out in a small flat- bottomed boat. In a great number of boating accidents it is found that the very simplest safety precautions were ignored. Lack of PFDs and overloading frequently set the stage for boating fatalities. Sadly, our larger group of boaters frequently overlooks the problem of boating safety. Boaters in this broad group are owners of small boats, often sportsmen. This is not to say that most of these folks are not safe boaters, but the figures show that sportsmen in this group in Pennsylvania regularly head the list of boating fatalities. There are more of them on the waterways and they probably make more frequent trips afloat than others. Thus, on a per capita or per-hour-of-boating basis, they may not actually deserve the top spot on the fatality list. Still, this reasoning does not save lives and that is what is WHO HAS BOATING important. ACCIDENTS? Most boating accidents happen in what is generally regarded as nice weather. Many tragedies happen on clear, warm days with light or no wind. However, almost half of all accidents involving fatalities occur in water less than 60 degrees. A great percentage of these fatal accidents involved individuals fishing or hunting from a john boat, canoe, or some other small craft. Not surprising is that victims of this type of boating accident die not because of the impact of the collision or the burns of a fire or explosion, but because they drown. -

Those Restless Little Boats on the Uneasiness of Japanese Power-Boat Gamblers

Course No. 3507/3508 Contemporary Japanese Culture and Society Lecture No. 15 Gambling ギャンブル・賭博 GAMBLING … a national obession. Gambling fascinates, because it is a dramatized model of life. As people make their way through life, they have to make countless decisions, big and small, life-changing and trivial. In gambling, those decisions are reduced to a single type – an attempt to predict the outcome of an event. Real-life decisions often have no clear outcome; few that can clearly be called right or wrong, many that fall in the grey zone where the outcome is unclear, unimportant, or unknown. Gambling decisions have a clear outcome in success or failure: it is a black and white world where the grey of everyday life is left behind. As a simplified and dramatized model of life, gambling fascinates the social scientist as well as the gambler himself. Can the decisions made by the gambler offer us a short-cut to understanding the character of the individual, and perhaps even the collective? Gambling by its nature generates concrete, quantitative data. Do people reveal their inner character through their gambling behavior, or are they different people when gambling? In this paper I will consider these issues in relation to gambling on powerboat races (kyōtei) in Japan. Part 1: Institutional framework Gambling is supposed to be illegal in Japan, under article 23 of the Penal Code, which prescribes up to three years with hard labor for any “habitual gambler,” and three months to five years with hard labor for anyone running a gambling establishment. Gambling is unambiguously defined as both immoral and illegal. -

Japanese Publicly Managed Gaming (Sports Gambling) and Local Government

Papers on the Local Governance System and its Implementation in Selected Fields in Japan No.16 Japanese Publicly Managed Gaming (Sports Gambling) and Local Government Yoshinori ISHIKAWA Executive director, JKA Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR) Institute for Comparative Studies in Local Governance (COSLOG) National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) Except where permitted by the Copyright Law for “personal use” or “quotation” purposes, no part of this booklet may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission. Any quotation from this booklet requires indication of the source. Contact Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR) (The International Information Division) Sogo Hanzomon Building 1-7 Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 102-0083 Japan TEL: 03-5213-1724 FAX: 03-5213-1742 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.clair.or.jp/ Institute for Comparative Studies in Local Governance (COSLOG) National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) 7-22-1 Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 106-8677 Japan TEL: 03-6439-6333 FAX: 03-6439-6010 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www3.grips.ac.jp/~coslog/ Foreword The Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR) and the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) have been working since FY 2005 on a “Project on the overseas dissemination of information on the local governance system of Japan and its operation”. On the basis of the recognition that the dissemination to overseas countries of information on the Japanese local governance system and its operation was insufficient, the objective of this project was defined as the pursuit of comparative studies on local governance by means of compiling in foreign languages materials on the Japanese local governance system and its implementation as well as by accumulating literature and reference materials on local governance in Japan and foreign countries. -

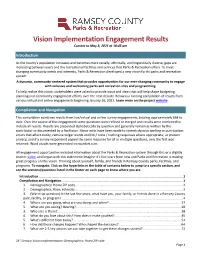

Vision Implementation Engagement Results Current to May 3, 2021 at 10:45 Am

Vision Implementation Engagement Results Current to May 3, 2021 at 10:45 am Introduction As the county’s population increases and becomes more racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse, gaps are increasing between users and the recreational facilities and services that Parks & Recreation offers. To meet changing community needs and interests, Parks & Recreation developed a new vision for its parks and recreation system: A dynamic, community-centered system that provides opportunities for our ever-changing community to engage with inclusive and welcoming parks and recreation sites and programming. To help realize this vision, stakeholders were asked to provide input and ideas that will help shape budgeting, planning and community engagement efforts over the next decade. Below is a running compilation of results from various virtual and online engagements beginning January 26, 2021. Learn more on the project website. Compilation and Navigation This compilation combines results from live/virtual and online survey engagements, totaling approximately 668 to date. Over the course of this engagement some questions were refined or merged and results were combined to include all results. Results are presented alphabetically by question and generally remain as written by the contributor or documented by a facilitator. Minor edits have been made to correct obvious spelling or punctuation errors that affect clarity, remove vulgar words and NA / none / nothing responses where appropriate, or protect privacy; and if a survey respondent copied the same response for all or multiple questions, only the first was retained. Word clouds were generated via wordart.com. All engagement opportunities included information about the Parks & Recreation system through this or a slightly shorter video, and began with this statement: Imagine it's five years from now and Parks and Recreation is making great progress on this vision. -

Peters & May Usa and Village of Itasca Unveil New U-11

PETERS & MAY USA AND VILLAGE OF ITASCA UNVEIL NEW U-11 HYDROPLANE Itasca, Illinois will be a hotbed of boat racing on Tuesday, June 28 th , when Peters & May USA and the U-11 Racing Group take over downtown’s Orchard Street to unveil the newly completed “Peters & May” hydroplane that will debut in the H1 Unlimited Air National Guard Race Series . Itasca is the corporate headquarters for Peters & May USA, the world-wide boat shipping company, and will be represented on-board the new boat when Mayor Jeff Pruyn applies the Village logo to the Peters & May hydroplane. The Village police department will also be on hand to display a special souped-up Subaru squad car, adding to the festivities scheduled from 2:00 – 6:00 p.m. The new 26-foot Hydroplane, powered by a T-55 Lycoming helicopter turbine producing more than 2600 horsepower, will be on display with its race support truck along with race driver JW Myers . Myers and his racing crew will be available to sign autographs and answer questions about the boat, hydroplane racing and race safety, while Peters & May USA will provide snacks and give-a-ways for the children in attendance. The boat is painted in a bright red and silver and will be hard to miss on display across from the train station. The Peters & May hydroplane joins a fleet of boats that are often named “Miss” by their owners and sponsors. Championship boats like Miss Budweiser helped make the sport famous by achieving speeds of over 200 mph and throwing wakes that are several stories high. -

MEDIA GUIDE 2016 7/26/2016 Revision 6

MEDIA GUIDE 2016 7/26/2016 Revision 6 TRI-CITY WATER FOLLIES MEDIA GUIDE 2016 HAPO APBA Columbia Cup for H1 Unlimited Hydroplanes HAPO Over-the-River Air Show Plumbers and Steamfitters UA Local 598 & Signatory Contractors Grand Prix West Regatta National Guard 5-Liter Hydroplane Regatta Legends of Thunder Vintage Hydroplane Demonstration July 29 – 31, 2016 Revision 2 - 7/26/2016 Get ready for the biggest weekend of hydroplane racing all year long! Don't miss this thrilling action on the water thanks to the H1 Unlimited Hydroplanes, plus the high speed action of Grand Prix, 5-Liter, and Vintage hydroplanes. Combine that action with the HAPO Over the River Air Show, and it's a weekend you won't want to miss. Mark your calendar now for July 29-31, 2016 , and enjoy the 50th year of Tri-Cities annual celebration of high-speed hydro action. We welcome back the H1 Unlimited Hydroplanes for the 2016 hydroplane racing series. The weekend would not be complete without the awesome aerial demonstrations presented by HAPO Community Credit Union. We are excited to have the HAPO Over the River Air Show Schedule: Lucas Oil Skydivers Lucal Oil Air Aerobatics with Mike Wiskus The Patriots Jet Team Yellow Thunder Power Addiction Air Shows with Brad Wursten US Coast Guard Search & Rescue Demonstrations Bring your family and friends and join us on the shores of the Columbia River for an action-packed, energy filled weekend. The Tri-Cities will host this full weekend of festivities; the world’s fastest race boats, Vintage hydroplanes, Grand Prix hydroplanes, 5-Liter Hydroplanes, 1-Liter Hydroplanes, the exciting Over-the-River Air Show, plus vendors and amenities along the shoreline. -

The Second Running of the Gold Cup Fast Boat Section Was Slightly Smaller in Size

The second running of the Gold Cup fast boat section was slightly smaller in size. Sponson damage from the madhouse start caused Muncey to withdraw the Atlas, so the first turn was not nearly as crowded, as the second section got under way. Chenowith put Miss Budweiser out front coming out of the first turn and they were followed by the Oberto, Squire Shop, and the Pay n’ Pak. The Thousand Trails went out early with a broken crankshaft. On Lap 2, Hanauer pushed the Squire ahead of a faltering Oberto and the Pak did the same on Lap 3. From there it was pretty much a boat parade as they continued to put distance between one another. The Bud averaged 113.782 for the win, nearly two miles per hour faster than the Squire. It was then all Miss Budweiser, wire-to-wire, as Chenowith produced a record setting performance in a hotly contested Gold Cup championship final. The beer boat’s five-lap average was both a Gold Cup and Lake Washington course record of 123.814 mph, as was the Bud’s Lap 3 circuit of the course at a blistering 127.728. While Hanauer and the Squire did their best to contend, the Pak was the closest pursuer for nearly the entire final. Staying on the Pak’s heels for three laps, Hanauer made his move at start of Lap 4 on the front straight and then gained significant ground on the Pak in the south turn. Cornering hard, he put the Squire into Lane 1 to make a final run on Walters as the two boats sailed through the floating bridge turn.