Naming and the Law in France

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of Kufic Script in Islamic Calligraphy and Its Relevance To

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1999 A study of Kufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century Enis Timuçin Tan University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Tan, Enis Timuçin, A study of Kufic crs ipt in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1999. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/1749 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. A Study ofKufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century. DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by ENiS TIMUgiN TAN, GRAD DIP, MCA FACULTY OF CREATIVE ARTS 1999 CERTIFICATION I certify that this work has not been submitted for a degree to any university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, expect where due reference has been made in the text. Enis Timucin Tan December 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge with appreciation Dr. Diana Wood Conroy, who acted not only as my supervisor, but was also a good friend to me. I acknowledge all staff of the Faculty of Creative Arts, specially Olena Cullen, Liz Jeneid and Associate Professor Stephen Ingham for the variety of help they have given to me. -

Family Law Form 12.982(A), Petition for Change of Name (Adult) (02/18) Copies, and the Clerk Can Tell You the Amount of the Charges

INSTRUCTIONS FOR FLORIDA SUPREME COURT APPROVED FAMILY LAW FORM 12.982(a) PETITION FOR CHANGE OF NAME (ADULT) (02/18) When should this form be used? This form should be used when an adult wants the court to change his or her name. This form is not to be used in connection with a dissolution of marriage or for adoption of child(ren). If you want a change of name because of a dissolution of marriage or adoption of child(ren) that is not yet final, the change of name should be requested as part of that case. This form should be typed or printed in black ink and must be signed before a notary public or deputy clerk. You should file the original with the clerk of the circuit court in the county where you live and keep a copy for your records. What should I do next? Unless you are seeking to restore a former name, you must have fingerprints submitted for a state and national criminal records check. The fingerprints must be taken in a manner approved by the Department of Law Enforcement and must be submitted to the Department for a state and national criminal records check. You may not request a hearing on the petition until the clerk of court has received the results of your criminal history records check. The clerk of court can instruct you on the process for having the fingerprints taken and submitted, including information on law enforcement agencies or service providers authorized to submit fingerprints electronically to the Department of Law Enforcement. -

Name Change Checklist

Name Change Checklist Government Agencies Social Security Administration Department of Motor Vehicles - driver's license, car title and registration Voter Registration US Passport Post Office, if change of address Military or Veteran Records Public Assistance Naturalization Papers Any open court orders Work and Employment W-4 Form 401k Health Insurance Benefits (including Beneficiaries) Email ID Card Business Cards Name Plate Work website / website contact information Unions Professional Organizations Professional Licenses Personal website – if you have a resume based website Banks / Financial Institutions Checking accounts, checks, and bank cards Savings and money market accounts, CDs Credit Cards Assets such as property titles, deeds, trusts Debts such as mortgages and personal loans Debts such as auto or school loans Investment accounts, including IRAs, and 401ks Insurance Policies such as life, disability Home Homeowners or renters insurance Landlord Home owners association or management agency Property Tax department / Tax assessor Utilities o Electric o Gas o Water / sewer o Telephones (including cell and landline) o Internet o Cable Auto Insurance Medical Doctor Dentist Ob-Gyn Therapists Counselors Eye Doctor Pharmacy Veterinarian / Micro Chip Company Personal School / School Records / Alumni Associations Groups, Associations, Organizations Subscriptions Airline Miles Programs Loyalty Clubs Road Toll Accounts Your Voicemail Gym Membership Church / Religious Organizations Other Legal Documents Health proxy Power of Attorney Will Living Trusts Your Attorney Social Media Facebook Twitter Pinterest LinkedIn Flickr Instagram Personal Blog or Website Email Accounts Brought to you by http://www.littlethingsfavors.com . -

Pro Se Name & Gender Change Guide for Transgender Residents Of

Pro Se Name & Gender Change Guide for Transgender Residents of Greater Capital Region, New York By, Lettie Dickerson, Esq., Milo Primeaux, Esq., Kevin M. Nelson 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER ................................................................................................................................................ 3 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ................................................................................................................. 4 SECTION 1: CHANGING YOUR NAME IN COURT ............................................................................ 6 STEP BY STEP OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................................. 6 PREPARING THE PETITION ............................................................................................................................ 8 ABOUT NAME CHANGE PUBLICATION REQUIREMENT ................................................................................... 9 NAME CHANGE APPLICATION CHECKLIST ...................................................................................................10 SECTION 2: UPDATING ID .....................................................................................................................11 SOCIAL SECURITY .......................................................................................................................................11 -

Gaelic Names of Plants

[DA 1] <eng> GAELIC NAMES OF PLANTS [DA 2] “I study to bring forth some acceptable work: not striving to shew any rare invention that passeth a man’s capacity, but to utter and receive matter of some moment known and talked of long ago, yet over long hath been buried, and, as it seemed, lain dead, for any fruit it hath shewed in the memory of man.”—Churchward, 1588. [DA 3] GAELIC NAMES OE PLANTS (SCOTTISH AND IRISH) COLLECTED AND ARRANGED IN SCIENTIFIC ORDER, WITH NOTES ON THEIR ETYMOLOGY, THEIR USES, PLANT SUPERSTITIONS, ETC., AMONG THE CELTS, WITH COPIOUS GAELIC, ENGLISH, AND SCIENTIFIC INDICES BY JOHN CAMERON SUNDERLAND “WHAT’S IN A NAME? THAT WHICH WE CALL A ROSE BY ANY OTHER NAME WOULD SMELL AS SWEET.” —Shakespeare. WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS EDINBURGH AND LONDON MDCCCLXXXIII All Rights reserved [DA 4] [Blank] [DA 5] TO J. BUCHANAN WHITE, M.D., F.L.S. WHOSE LIFE HAS BEEN DEVOTED TO NATURAL SCIENCE, AT WHOSE SUGGESTION THIS COLLECTION OF GAELIC NAMES OF PLANTS WAS UNDERTAKEN, This Work IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED BY THE AUTHOR. [DA 6] [Blank] [DA 7] PREFACE. THE Gaelic Names of Plants, reprinted from a series of articles in the ‘Scottish Naturalist,’ which have appeared during the last four years, are published at the request of many who wish to have them in a more convenient form. There might, perhaps, be grounds for hesitation in obtruding on the public a work of this description, which can only be of use to comparatively few; but the fact that no book exists containing a complete catalogue of Gaelic names of plants is at least some excuse for their publication in this separate form. -

PRELIMINARY STAFF REPORT To: City Planning Commission Prepared By: Nicolette Jones, Stosh Kozlowski, Laura Baños, and Derreck Deason Date: February 16, 2015

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION CITY OF NEW ORLEANS MITCHELL J. LANDRIEU ROBERT D. RIVERS MAYOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR LESLIE T. ALLEY DEPUTY DIRECTOR City Planning Commission Staff Report Executive Summary Consideration: Request by City Council Motion M-15-444 for the City Planning Commission to conduct a study and public hearing to amend its Administrative Rules, Policies, & Procedures relative to the creation of an honorary street name change process. Background: To date, the City of New Orleans does not have a policy related to an honorary street dedication program. Currently, the City’s street naming policy, which is documented in the City Planning Commission’s Administrative Rules, Policies, and Procedures, only delineates the procedure for street name changes. An honorary street dedication program, which many other jurisdictions across the country have implemented, allows cities the opportunity to commemorate individuals and groups who have made significant contributions to the community, but without causing any disruption of the existing street grid associated with a modification to the Official Map as would a permanent street name change. According to best practices, honorary street signage is typically a secondary sign that is installed above or below an existing street name sign. The City Council has granted honorary street dedications in the recent past, though without a formalized policy to guide the process. Following the recent approval of street name changes in the spring of 2015, the New Orleans City Council requested that the City Planning Commission review the City’s street renaming rules and explore opportunities to create an honorary street dedication program. Recommendation: In order to promote clear wayfinding, efficient emergency response and service delivery, as well as accurate address keeping, the staff advises against frequent changes to the City’s Official Map. -

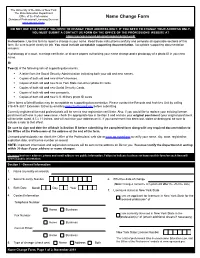

Name Change Form Division of Professional Licensing Services

The University of the State of New York The State Education Department Office of the Professions Name Change Form Division of Professional Licensing Services www.op.nysed.gov DO NOT USE THIS FORM IF YOU NEED TO CHANGE YOUR ADDRESS ONLY. IF YOU NEED TO CHANGE YOUR ADDRESS ONLY, YOU MUST SUBMIT A CONTACT US FORM ON THE OFFICE OF THE PROFESSIONS' WEBSITE AT https://eservices.nysed.gov/professions/contact-us/#/ Instructions: Use this form to report a change in your name. Read these instructions carefully and complete all applicable sections of this form. Be sure to print clearly in ink. You must include acceptable supporting documentation. Acceptable supporting documentation includes: A photocopy of a court, marriage certificate, or divorce papers authorizing your name change and a photocopy of a photo ID in your new name. Or Two (2) of the following sets of supporting documents: ● A letter from the Social Security Administration indicating both your old and new names. ● Copies of both old and new driver's licenses. ● Copies of both old and new New York State non-driver photo ID cards. ● Copies of both old and new Social Security Cards. ● Copies of both old and new passports. ● Copies of both old and new U.S. Military photo ID cards. Other forms of identification may be acceptable as supporting documentation. Please contact the Records and Archives Unit by calling 518-474-3817 Extension 380 or by emailing [email protected] before submitting. Currently registered licensed professionals will be sent a new registration certificate. Also, if you would like to replace your existing license parchment with one in your new name, check the appropriate box in Section II and enclose your original parchment (your original parchment will be letter sized, 8.5 x 11 inches, and will not have your address on it). -

Putting Frisian Names on the Map

GEGN.2/2021/68/CRP.68 15 March 2021 English United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names Second session New York, 3 – 7 May 2021 Item 12 of the provisional agenda * Geographical names as culture, heritage and identity, including indigenous, minority and regional languages and multilingual issues Putting Frisian names on the map Submitted by the Netherlands** * GEGN.2/2021/1 ** Prepared by Jasper Hogerwerf, Kadaster GEGN.2/2021/68/CRP.68 Introduction Dutch is the national language of the Netherlands. It has official status throughout the Kingdom of the Netherlands. In addition, there are several other recognized languages. Papiamentu (or Papiamento) and English are formally used in the Caribbean parts of the Kingdom, while Low-Saxon and Limburgish are recognized as non-standardized regional languages, and Yiddish and Sinte Romani as non-territorial minority languages in the European part of the Kingdom. The Dutch Sign Language is formally recognized as well. The largest minority language is (West) Frisian or Frysk, an official language in the province of Friesland (Fryslân). Frisian is a West Germanic language closely related to the Saterland Frisian and North Frisian languages spoken in Germany. The Frisian languages as a group are closer related to English than to Dutch or German. Frisian is spoken as a mother tongue by about 55% of the population in the province of Friesland, which translates to some 350,000 native speakers. In many rural areas a large majority speaks Frisian, while most cities have a Dutch-speaking majority. A standardized Frisian orthography was established in 1879 and reformed in 1945, 1980 and 2015. -

Hordern House Rare Books Pty

77 vICTORIA STREET • POTTS POINT • SyDNEy NSw 2011 • AUSTRAlia • TElephONE (02) 9356 4411 • fAx (02) 9357 3635 HORDERN HOUSE RARE BOOKS PTY. LTD. A.B.N. 94 193 459 772 E-MAIL: [email protected] INTERNET: www.hordern.com DIRECTORS: ANNE McCORMICK • DEREK McDONNELL HORDERN HOUSE RARE BOOKS • MANUSCRIPTS • PAINTINGS • PRINTS • RARE BOOKS • MANUSCRIPTS • PAINTINGS • PRINTS • RARE BOOKS • MANUSCRIPTS • PAINTINGS Acquisitions • October 2015 Important Works on Longitude 2. [BOARD OF LONGITUDE]. The 3. [BUREAU DES LONGITUDES]. Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Connaissance des tems, a l’usage des Ephemeris, for the Year 1818. Astronomes et des Navigateurs pour l’an X… Octavo, very good in original polished calf, faithfully rebacked. London, John Octavo, folding world map and two Murray 1815. folding tables; an attractive copy in contemporary marbled calf, gilt, red Rare copy of the Nautical Almanac for spine label. Paris, l’Imprimerie de la 1818, a fundamental inclusion in the République, Fructidor, An VII, that is shipboard library of any Admiralty- circa August 1799. sponsored voyage. The Almanac was used for reckoning the longitude at sea A handsome copy of this rare work by the lunar method, and was closely by the French Bureau des Longitudes, studied by officers of the Royal Navy. for use by naval officers for the year The continued publication of such 1802 and 1803. The volume includes a almanacs is further proof that the handsome map of the world showing invention of the chronometer, (whilst the track of a solar eclipse that revolutionary), did not completely occurred in August of that year. Much supersede the necessity for other fail- like the British equivalent, these tables 1. -

Šiauliai University Faculty of Humanities Department of English Philology

ŠIAULIAI UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PHILOLOGY RENDERING OF GERMANIC PROPER NAMES IN THE LITHUANIAN PRESS BACHELOR THESIS Research Adviser: Assist. L.Petrulion ė Student: Aist ė Andži ūtė Šiauliai, 2010 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................3 1. THE CONCEPTION OF PROPER NAMES.........................................................................5 1.2. The development of surnames.............................................................................................6 1.3. Proper names in Germanic languages .................................................................................8 1.3.1. Danish, Norwegian, Swedish and Icelandic surnames.................................................9 1.3.2. Dutch surnames ..........................................................................................................12 1.3.3. English surnames........................................................................................................13 1.3.4. German surnames .......................................................................................................14 2. NON-LITHUANIAN SURNAMES ORTHOGRAPHY .....................................................16 2.1. The historical development of the problem.......................................................................16 2.2. The rules of transcriptions of non-Lithuanian proper names ............................................22 3. THE USAGE -

Firearms in and Around Thomas Pynchon's Mason & Dixon

ISSN: 2044-4095 Author(s): Umberto Rossi Affiliation(s): Independent Researcher Title: “Something More Than a Rifle”: Firearms in and around Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon Date: 2014 Volume: 2 Issue: 2 URL: https://www.pynchon.net/owap/article/view/77 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7766/orbit.v2.2.77 Abstract: This article aims to carry out a multidisciplinary reading of Mason & Dixon starting from the apparitions of what might only look like a "stage prop", a rifle in four more or less important moments of the novel. By applying a stereoscopic reading of the novel, which may achieve depth by means of comparing different textual objects and a wider historical context (that of the history of firearms in the 17th and 18th century, plus other works by Pynchon featuring firearms), it will be shown how literary (textual) avatars of "real", "historical" objects (firearms) may at the same time be verbal constructs but refer to the technical, material features of those objects, establishing multi-dimensional and complex relations between technology, science, economics (early forms of globalization), politics (colonialism and colonial wars) within and outside Mason & Dixon, and the rest of Pynchon's oeuvre. Moreover, this reading allows us to better understand how Pynchon may use the historical documents and literature he has found while researching his novels. “Something More Than a Rifle”: Firearms in and around Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon Umberto Rossi …while Freud says that sometimes a cigar is only a cigar, a rifle is 1 always something more than a rifle. – William T. Vollmann “I say, Pugnax—what’s that you’re reading now, old fellow?” “Rr Rff-rff Rr-rr-rff-rrf-rrf,” replied Pugnax without looking up, which Darby, having like the others in the crew got used to Pugnax’s voice (…), now interpreted as “The Princess Casamassima” (AtD 5-6) This small comedic episode from the first chapter of Against the Day is an example of the stereoscopic effect that plays an important role in the experience of reading Thomas Pynchon’s fiction. -

WHERE WAS MEAN SOLAR TIME FIRST ADOPTED? Simone Bianchi INAF-Osservatorio Astrofisico Di Arcetri, Largo E. Fermi, 5, 50125, Flor

WHERE WAS MEAN SOLAR TIME FIRST ADOPTED? Simone Bianchi INAF-Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo E. Fermi, 5, 50125, Florence, Italy [email protected] Abstract: It is usually stated in the literature that Geneva was the first city to adopt mean solar time, in 1780, followed by London (or the whole of England) in 1792, Berlin in 1810 and Paris in 1816. In this short paper I will partially revise this statement, using primary references when available, and provide dates for a few other European cities. Although no exact date was found for the first public use of mean time, the primacy seems to belong to England, followed by Geneva in 1778–1779 (for horologists), Berlin in 1810, Geneva in 1821 (for public clocks), Vienna in 1823, Paris in 1826, Rome in 1847, Turin in 1849, and Milan, Bologna and Florence in 1860. Keywords: mean solar time 1 INTRODUCTION The inclination of the Earth’s axis with respect to the orbital plane and its non-uniform revolution around the Sun are reflected in the irregularity of the length of the day, when measured from two consecutive passages of the Sun on the meridian. Though known since ancient times, the uneven length of true solar days became of practical interest only after Christiaan Huygens (1629 –1695) invented the high-accuracy pendulum clock in the 1650s. For proper registration of regularly-paced clocks, it then became necessary to convert true solar time into mean solar time, obtained from the position of a fictitious mean Sun; mean solar days all having the same duration over the course of the year.