Bede, St Cuthbert and the Science of Miracles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evangelicalism and the Church of England in the Twentieth Century

STUDIES IN MODERN BRITISH RELIGIOUS HISTORY Volume 31 EVANGELICALISM AND THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY REFORM, RESISTANCE AND RENEWAL Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 1 25/07/2014 10:00 STUDIES IN MODERN BRITISH RELIGIOUS HISTORY ISSN: 1464-6625 General editors Stephen Taylor – Durham University Arthur Burns – King’s College London Kenneth Fincham – University of Kent This series aims to differentiate ‘religious history’ from the narrow confines of church history, investigating not only the social and cultural history of reli- gion, but also theological, political and institutional themes, while remaining sensitive to the wider historical context; it thus advances an understanding of the importance of religion for the history of modern Britain, covering all periods of British history since the Reformation. Previously published volumes in this series are listed at the back of this volume. Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 2 25/07/2014 10:00 EVANGELICALISM AND THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY REFORM, RESISTANCE AND RENEWAL EDITED BY ANDREW ATHERSTONE AND JOHN MAIDEN THE BOYDELL PRESS Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 3 25/07/2014 10:00 © Contributors 2014 All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2014 The Boydell Press, Woodbridge ISBN 978-1-84383-911-8 The Boydell Press is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. -

John Thomas Mullock: What His Books Reveal

John Thomas Mullock: What His Books Reveal Ágnes Juhász-Ormsby The Episcopal Library of St. John’s is among the few nineteenth- century libraries that survive in their original setting in the Atlantic provinces, and the only one in Newfoundland and Labrador.1 It was established by John Thomas Mullock (1807–69), Roman Catholic bishop of Newfoundland and later of St. John’s, who in 1859 offered his own personal collection of “over 2500 volumes as the nucleus of a Public Library.” The Episcopal Library in many ways differs from the theological libraries assembled by Mullock’s contemporaries.2 When compared, for example, to the extant collection of the Catholic bishop of Victoria, Charles John Seghers (1839–86), whose life followed a similar pattern to Mullock’s, the division in the founding collection of the Episcopal Library between the books used for “private” as opposed to “public” theological study becomes even starker. Seghers’s books showcase the customary stock of a theological library with its bulky series of manuals of canon law, collections of conciliar and papal acts and bullae, and practical, dogmatic, moral theological, and exegetical works by all the major authors of the Catholic tradition.3 In contrast to Seghers, Mullock’s library, although containing the constitutive elements of a seminary library, is a testimony to its found- er’s much broader collecting habits. Mullock’s books are not restricted to his philosophical and theological studies or to his interest in univer- sal church history. They include literary and secular historical works, biographies, travel books, and a broad range of journals in different languages that he obtained, along with other necessary professional 494 newfoundland and labrador studies, 32, 2 (2017) 1719-1726 John Thomas Mullock: What His Books Reveal tools, throughout his career. -

St Cuthbert Story

Cuthbert was born about the year 634 (about 1400 years ago!) He lived in Melrose in Southern Scotland. He liked to walk in the hills. One night, when he was helping to look after sheep he thought he saw angels taking a soul to heaven. A few days later he found out Saint Aidan had died. Cuthbert decided to become a monk. He became a monk at the monastery in Melrose where he met Boisil, the prior of the monastery. Boisil taught Cuthbert for 6 years. Before Boisil died, he told Cuthbert he would be a Bishop one day. Cuthbert liked to visit lonely farms and villages. Crowds of people came to visit him. He lived at Melrose monastery for 13 years. Cuthbert was sent to be Prior of Lindisfarne. Cuthbert taught the monks the new Roman church rules. Some of the monks did not like the new rules and Cuthbert had to be very patient with them. After 12 years, Cuthbert went to live on a quiet island 7 miles away from Lindisfarne. Cuthbert lived on this small island for 3 years. He grew barley and vegetables and his monks dug a well and built a guest house for visitors. The King asked Cuthbert to be Bishop of Hexham. Cuthbert didn’t want to but he still remembered what Boisil had said. Cuthbert did not want to be Bishop of Hexham but agreed to be Bishop of Lindisfarne instead. He was very sad to have to leave his small island. Cuthbert was Bishop of Lindisfarne for 2 years. The people loved him. -

The Venerable Bede a Celebration

The Venerable Bede A Celebration Monday 25 May 2020 5.15 p.m. The Venerable Bede Bede served in the monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow for all his life, and died in Jarrow in 735 aged about 62. In 1020, his body was brought to Durham to be placed with the body of St Cuthbert. Bede’s body was brought to its final resting place in the Galilee Chapel in 1370. Introit Christ is the Morning Star Christ is the Morning Star who when the night of this world is past brings to his saints the promise of the light of life and opens everlasting day. Alleluia. The Venerable Bede Richard Lloyd The Dean welcomes the people Hymn We sing to God in praise of Bede (tune NEH 431) We sing to God in praise of Bede, The prince of scholars in his age, Christ’s servant, lover of God’s word, Once monk of Jarrow, priest and sage. For his example we give thanks, His zeal to learn, his skill to write; Like him we long to know God’s ways And in God’s word drink with delight. Grant us, good Lord, one day to come To you, all wisdom’s fountainhead, With Bede to stand before your face, Our Saviour, living from the dead. Teach us, O Lord, like Bede to pray, To make the word of God our joy, Exult in music, song and art, In worship all your gifts employ. O Christ, our glorious Morning Star, Come with the passing of the night, Bring to your saints th’eternal day, The promise of your life and light. -

Of St Cuthbert'

A Literary Pilgrimage of Durham by Ruth Robson of St Cuthbert' 1. Market Place Welcome to A Literary Pilgrimage of Durham, part of Durham Book Festival, produced by New Writing North, the regional writing development agency for the North of England. Durham Book Festival was established in the 1980s and is one of the country’s first literary festivals. The County and City of Durham have been much written about, being the birthplace, residence, and inspiration for many writers of both fact, fiction, and poetry. Before we delve into stories of scribes, poets, academia, prize-winning authors, political discourse, and folklore passed down through generations, we need to know why the city is here. Durham is a place steeped in history, with evidence of a pre-Roman settlement on the edge of the city at Maiden Castle. Its origins as we know it today start with the arrival of the community of St Cuthbert in the year 995 and the building of the white church at the top of the hill in the centre of the city. This Anglo-Saxon structure was a precursor to today’s cathedral, built by the Normans after the 1066 invasion. It houses both the shrine of St Cuthbert and the tomb of the Venerable Bede, and forms the Durham UNESCO World Heritage Site along with Durham Castle and other buildings, and their setting. The early civic history of Durham is tied to the role of its Bishops, known as the Prince Bishops. The Bishopric of Durham held unique powers in England, as this quote from the steward of Anthony Bek, Bishop of Durham from 1284-1311, illustrates: ‘There are two kings in England, namely the Lord King of England, wearing a crown in sign of his regality and the Lord Bishop of Durham wearing a mitre in place of a crown, in sign of his regality in the diocese of Durham.’ The area from the River Tees south of Durham to the River Tweed, which for the most part forms the border between England and Scotland, was semi-independent of England for centuries, ruled in part by the Bishop of Durham and in part by the Earl of Northumberland. -

The Commemoration of Founders and Benefactors at the Heart of Durham: City, County and Region

The Commemoration of Founders and Benefactors at the heart of Durham: City, County and Region Address: Professor Stuart Corbridge Vice-Chancellor University of Durham Sunday 22 November 2020 3.30 p.m. VOLUMUS PRÆTEREA UT EXEQUIÆ SINGULIS ANNIS PERPETUIS TEMPORIBUS IN ECCLESIA DUNELMENSI, CONVOCATIS AD EAS DECANO OMNIBUS CANONICIS ET CÆTERIS MINISTRIS SCHOLARIBUS ET PAUPERIBUS, PRO ANIMABUS CHARISSIMORUM PROGENITORUM NOSTRORUM ET OMNIUM ANTIQUI CŒNOBII DUNELMENSIS FUNDATORUM ET BENEFACTORUM, VICESIMO SEPTIMO DIE JANUARII CUM MISSÂ IN CRASTINO SOLENNITER CELEBRENTUR. Moreover it is our will that each year for all time in the cathedral church of Durham on the twenty-seventh day of January, solemn rites of the dead shall be held, together with mass on the following day, for the souls of our dearest ancestors and of all the founders and benefactors of the ancient convent of Durham, to which shall be summoned the dean, all the canons, and the rest of the ministers, scholars and poor men. Cap. 34 of Queen Mary’s Statutes of Durham Cathedral, 1554 Translated by Canon Dr David Hunt, March 2014 2 Welcome Welcome to the annual commemoration of Founders and Benefactors. This service gives us an opportunity to celebrate those whose generosity in the past has enriched the lives of Durham’s great institutions today and to look forward to a future that is full of opportunity. On 27 January 1914, the then Dean, Herbert Hensley Henson, revived the Commemoration of Founders and Benefactors. It had been written into the Cathedral Statutes of 1554 but for whatever reason had not been observed for centuries. -

J?, ///? Minor Professor

THE PAPAL AGGRESSION! CREATION OF THE ROMAN CATHOLIC HIERARCHY IN ENGLAND, 1850 APPROVED! Major professor ^ J?, ///? Minor Professor ItfCp&ctor of the Departflfejalf of History Dean"of the Graduate School THE PAPAL AGGRESSION 8 CREATION OP THE SOMAN CATHOLIC HIERARCHY IN ENGLAND, 1850 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For she Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Denis George Paz, B. A, Denton, Texas January, 1969 PREFACE Pope Plus IX, on September 29» 1850, published the letters apostolic Universalis Sccleslae. creating a terri- torial hierarchy for English Roman Catholics. For the first time since 1559» bishops obedient to Rome ruled over dioceses styled after English place names rather than over districts named for points of the compass# and bore titles derived from their sees rather than from extinct Levantine cities« The decree meant, moreover, that6 in the Vati- k can s opinionc England had ceased to be a missionary area and was ready to take its place as a full member of the Roman Catholic communion. When news of the hierarchy reached London in the mid- dle of October, Englishmen protested against it with unexpected zeal. Irate protestants held public meetings to condemn the new prelates» newspapers cried for penal legislation* and the prime minister, hoping to strengthen his position, issued a public letter in which he charac- terized the letters apostolic as an "insolent and insidious"1 attack on the queen's prerogative to appoint bishops„ In 1851» Parliament, despite the determined op- position of a few Catholic and Peellte members, enacted the Ecclesiastical Titles Act, which imposed a ilOO fine on any bishop who used an unauthorized territorial title, ill and permitted oommon informers to sue a prelate alleged to have violated the act. -

The Appropriation of St Cuthbert: Architecture, History-Writing, and Ecclesiastical Politics in Durham, 1083-1250

Quidditas Volume 29 Article 4 2008 The Appropriation of St Cuthbert: Architecture, History-writing, and Ecclesiastical Politics in Durham, 1083-1250 John D. Young Flagler College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Young, John D. (2008) "The Appropriation of St Cuthbert: Architecture, History-writing, and Ecclesiastical Politics in Durham, 1083-1250," Quidditas: Vol. 29 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol29/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 26 Quidditas The Appropriation of St Cuthbert: Architecture, History-writing, and Ecclesiastical Politics in Durham, 1083-1250 John D. Young Flagler College This paper describes the use of the cult of Saint Cuthbert in the High Middle Ages by both the bishops of Durham and the Benedictine community that was tied to the Episcopal see. Its central contention is that the churchmen of Durham adapted this popular cult to the political expediencies of the time. In the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries, when Bishop William de St. Calais ousted the entrenched remnants of the Lindisfarne community and replaced them with Benedictines, Cuthbert was primarily a monastic saint and not, as he would become, a popular pilgrimage saint. However, once the Benedictine community was firmly entrenched in Durham, the bishops, most prominently Hugh de Puiset, sought to create a saint who would appeal to a wide audience of pilgrims, including the women who had been excluded from direct worship in the earlier, Benedictine version of the saint. -

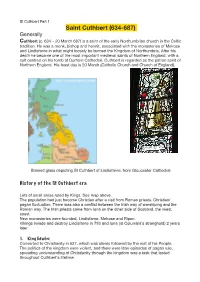

St Cuthbert Part 1 Saint Cuthbert (634-687) Generally Cuthbert (C

St Cuthbert Part 1 Saint Cuthbert (634-687) Generally Cuthbert (c. 634 – 20 March 687) is a saint of the early Northumbrian church in the Celtic tradition. He was a monk, bishop and hermit, associated with the monasteries of Melrose and Lindisfarne in what might loosely be termed the Kingdom of Northumbria. After his death he became one of the most important medieval saints of Northern England, with a cult centred on his tomb at Durham Cathedral. Cuthbert is regarded as the patron saint of Northern England. His feast day is 20 March (Catholic Church and Church of England), Stained glass depicting St Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, from Gloucester Cathedral History of the St Cuthbert era Lots of small areas ruled by Kings. See map above. The population had just become Christian after a visit from Roman priests. Christian/ pagan fluctuation. There was also a conflict between the Irish way of worshiping and the Roman way. The Irish priests came from Iona on the other side of Scotland, the /west coast. New monasteries were founded, Lindisfarne, Melrose and Ripon. Vikings invade and destroy Lindisfarne in 793 and Iona (st Columbia’s stronghold) 2 years later. 1. King Edwin: Converted to Christianity in 627, which was slowly followed by the rest of his People. The politics of the kingdom were violent, and there were later episodes of pagan rule, spreading understanding of Christianity through the kingdom was a task that lasted throughout Cuthbert's lifetime. Edwin had been baptised by Paulinus of York, an Italian who had come with the Gregorian mission from Rome. -

Catalogue 2017

Adopt a Book Catalogue 2017 1. Claudius Ptolomaeus, Geographia; Venice, 1562 – H.III.16 In his Geographia, Greek astronomer and polymath Claudius Ptolemy offered instruction in laying out maps by three different methods of projection; provided coordinates for some eight thousand places; and treated such basic concepts as geographical latitude and longitude. A best seller both in the age of luxurious manuscripts and in that of print, Ptolemy's Geography became one of the most influential cartographical manuals in history. Maps based on scientific principles had been produced in Europe as early as the 3rd century B.C.; however, Ptolemy’s work was different in that it offered instruction in the art of map projection. Its translation, first into Arabic in the 9th century, and then later into Latin in the 14th century, was seen as strongly influencing the cartographic traditions of both the Medieval Caliphate and Renaissance Europe. Columbus – one of its many readers – found inspiration in Ptolemy's exaggerated value for the size of Asia for his own fateful journey to the west. It was a key source for the maps of prominent cartographers including Martellus and Waldseemueller. ADOPTED £80 2. John Shute Barrington, Theological Works; London, 1828 – Q.X.62-64 The Barrington who authored this work is not the Shute Barrington who would serve as Bishop of Durham over a thirty five year period (who also published extensively on matters theological), but rather his father, John Shute Barrington, the 1st Viscount Barrington, a “politician and Christian apologist”. Barrington began publishing his theological works anonymously in 1701, with the publication of his essay concerning England and its Protestant dissidents; later editing this and publishing it under his own name, he followed it with works on The rights of Protestant dissenters and later, A dissuasive from Jacobitism. -

Disaster Response and Ecclesiastical Privilege in the Late Middle Ages: the Liberty of Durham After the Black Death

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Major Papers Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers October 2020 Disaster Response and Ecclesiastical Privilege in the Late Middle Ages: The Liberty of Durham After the Black Death John K. Mennell uWindsor, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/major-papers Part of the European History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Mennell, John K., "Disaster Response and Ecclesiastical Privilege in the Late Middle Ages: The Liberty of Durham After the Black Death" (2020). Major Papers. 147. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/major-papers/147 This Major Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in Major Papers by an authorized administrator of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Disaster Response and Ecclesiastical Privilege in the Late Middle Ages: The Liberty of Durham After the Black Death By John Keewatin Mennell A Major Research Paper Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Department of History in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2020 © 2020 John Keewatin Mennell Disaster Response and Ecclesiastical Privilege in the Late Middle Ages: The Liberty of Durham After the Black Death By John Keewatin Mennell APPROVED BY: _______________________________________ A. Pole Department of History _______________________________________ G. Lazure, Advisor Department of History August 31st, 2020 DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I hereby certify that I am the sole author of this thesis and that no part of this thesis has been published or submitted for publication. -

69-19,257 STOLTZ, Linda Elizabeth, 1938- the DEVELOPMENT OF

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE LEGEND OF ST. CUTHBERT Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Stoltz, Linda Elizabeth, 1938- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 21:02:21 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/287860 This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 69-19,257 STOLTZ, Linda Elizabeth, 1938- THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE LEGEND OF ST. CUTHBERT. University of Arizona, Ph.D., 1969 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE DEVELOPMENT OP THE LEGEND OP ST. CUTHBERT by Linda Elizabeth Stoltz A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 9 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Linda Elizabeth Stoltz entitled The Development of the Legend of St. Cuthbert be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy LSIL jf/r. / /9/9 Disseycation Director Date After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:-• Z- y£~ ir ApJ /9S? $ Lin— • /5 l*L°l ^ ^7^ /(, if6? C^u2a,si*-> /4 /f(?,7 .