Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Value of Books

The Value of Books: The York Minster Library as a social arena for commodity exchange. Master’s thesis, 60 credits, Spring 2018 Author: Luke Kelly Supervisor: Gudrun Andersson Seminar chair: Dag Lindström Date: 12/01/2018 HISTORISKA INSTITUTIONEN It would be the height of ignorance, and a great irony, if within a work focused on the donations of books, that the author fails to acknowledge and thank those who assisted in its production. Having been distant from both Uppsala and close friends whilst writing this thesis, (and missing dearly the chances to talk to others in person), it goes without saying that this work would not be possible if I had not had the support of many generous and wonderful people. Although to attempt to thank all those who assisted would, I am sure, fail to acknowledge everyone, a few names should be highlighted: Firstly, thank you to all of my fellow EMS students – the time spent in conversation over coffees shaped more of this thesis than you would ever realise. Secondly, to Steven Newman and all in the York Minster Library – without your direction and encouragement I would have failed to start, let alone finish, this thesis. Thirdly, to all members of History Node, especially Mikael Alm – the continued enthusiasm felt from you all reaches further than you know. Fourthly, to my family and closest – thank you for supporting (and proof reading, Maja Drakenberg) me throughout this process. Any success of the work can be attributed to your assistance. Finally, to Gudrun Andersson – thank you for offering guidance and support throughout this thesis’ production. -

Evangelicalism and the Church of England in the Twentieth Century

STUDIES IN MODERN BRITISH RELIGIOUS HISTORY Volume 31 EVANGELICALISM AND THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY REFORM, RESISTANCE AND RENEWAL Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 1 25/07/2014 10:00 STUDIES IN MODERN BRITISH RELIGIOUS HISTORY ISSN: 1464-6625 General editors Stephen Taylor – Durham University Arthur Burns – King’s College London Kenneth Fincham – University of Kent This series aims to differentiate ‘religious history’ from the narrow confines of church history, investigating not only the social and cultural history of reli- gion, but also theological, political and institutional themes, while remaining sensitive to the wider historical context; it thus advances an understanding of the importance of religion for the history of modern Britain, covering all periods of British history since the Reformation. Previously published volumes in this series are listed at the back of this volume. Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 2 25/07/2014 10:00 EVANGELICALISM AND THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY REFORM, RESISTANCE AND RENEWAL EDITED BY ANDREW ATHERSTONE AND JOHN MAIDEN THE BOYDELL PRESS Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 3 25/07/2014 10:00 © Contributors 2014 All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2014 The Boydell Press, Woodbridge ISBN 978-1-84383-911-8 The Boydell Press is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. -

Subject Guide 1 – Records Relating to Inclosure

Durham County Record Office County Hall Durham DH1 5UL Telephone: 03000 267619 Email: [email protected] Website: www.durhamrecordoffice.org.uk Subject Guide 1 – Records Relating to Inclosure Issue no. 19 July 2020 Contents Introduction 1 Organisation of List 2 Alphabetical List of Townships 2 A 2 B 2 C 3 D 4 E 4 F 4 G 4 H 5 I 5 K 5 L 5 M 6 N 6 O 6 R 6 S 7 T 7 U 8 W 8 Introduction Inclosure (occasionally spelled “enclosure”) refers to a reorganisation of scattered land holdings by mutual agreement of the owners. Much inclosure of Common Land, Open Fields and Moor Land (or Waste), formerly farmed collectively by the residents on behalf of the Lord of the Manor, had taken place by the 18th century, but the uplands of County Durham remained largely unenclosed. Inclosures, to consolidate land-holdings, divide the land (into Allotments) and fence it off from other usage, could be made under a Private Act of Parliament or by general agreement of the landowners concerned. In the latter case the Agreement would be Enrolled as a Decree at the Court of Chancery in Durham and/or lodged with the Clerk of the Peace, the senior government officer in the County, so may be preserved in Quarter Sessions records. In the case of Parliamentary Enclosure a Local Bill would be put before Parliament which would pass it into law as an Inclosure Act. The Acts appointed Commissioners to survey the area concerned and determine its distribution as a published Inclosure Award. -

John Thomas Mullock: What His Books Reveal

John Thomas Mullock: What His Books Reveal Ágnes Juhász-Ormsby The Episcopal Library of St. John’s is among the few nineteenth- century libraries that survive in their original setting in the Atlantic provinces, and the only one in Newfoundland and Labrador.1 It was established by John Thomas Mullock (1807–69), Roman Catholic bishop of Newfoundland and later of St. John’s, who in 1859 offered his own personal collection of “over 2500 volumes as the nucleus of a Public Library.” The Episcopal Library in many ways differs from the theological libraries assembled by Mullock’s contemporaries.2 When compared, for example, to the extant collection of the Catholic bishop of Victoria, Charles John Seghers (1839–86), whose life followed a similar pattern to Mullock’s, the division in the founding collection of the Episcopal Library between the books used for “private” as opposed to “public” theological study becomes even starker. Seghers’s books showcase the customary stock of a theological library with its bulky series of manuals of canon law, collections of conciliar and papal acts and bullae, and practical, dogmatic, moral theological, and exegetical works by all the major authors of the Catholic tradition.3 In contrast to Seghers, Mullock’s library, although containing the constitutive elements of a seminary library, is a testimony to its found- er’s much broader collecting habits. Mullock’s books are not restricted to his philosophical and theological studies or to his interest in univer- sal church history. They include literary and secular historical works, biographies, travel books, and a broad range of journals in different languages that he obtained, along with other necessary professional 494 newfoundland and labrador studies, 32, 2 (2017) 1719-1726 John Thomas Mullock: What His Books Reveal tools, throughout his career. -

CHRIST CHURCH LIBRARY NEWSLETTER Volume 1, Issue 1 Michaelmas 2004

CHRIST CHURCH LIBRARY NEWSLETTER Volume 1, Issue 1 Michaelmas 2004 Introducing OLIS at Christ Welcome to the Library Church This spacious College Library is an important At present the main catalogue and all management resource centre, primarily intended to provide functions of our library are run via Heritage 3.1 This undergraduate and graduate members of the college is a DOS-based library management system. with the books needed for their courses. We are happy to have you among our readers and The Library is currently in the process of preparing we’ll do everything we can to help. For queries, book the migration of all holdings onto OLIS, the Oxford recalls, book suggestions, please ask any member of Libraries Information System. At the moment only the staff at the front desk. part of the early printed books collection is available in OLIS. OLIS is the library catalogue and library system of Upper Library Tours the University of Oxford. It contains records for over eight million items (mainly books and periodicals) Undergraduates and postgraduates are invited on held by libraries within, or associated with, the Saturday of 0 week to a tour of the Upper Library. If University of Oxford. you could not join in at the date mentioned above, please find a member of staff on your first visit to the It can be searched using the internet and is open to Library so that you can be given a quick tour. the general public, not just members of the University. It contains both bibliographic data, such as an item's author and title, and Oxford-specific holdings data, for example which OLIS libraries have a copy and whether these copies are currently on loan. -

The North Pennines

LANDSCAPE CHARACTER THE NORTH PENNINES The North Pennines The North Pennines The North Pennines Countryside Character Area County Boundary Key characteristics • An upland landscape of high moorland ridges and plateaux divided by broad pastoral dales. • Alternating strata of Carboniferous limestones, sandstones and shales give the topography a stepped, horizontal grain. • Millstone Grits cap the higher fells and form distinctive flat-topped summits. Hard igneous dolerites of the Great Whin Sill form dramatic outcrops and waterfalls. • Broad ridges of heather moorland and acidic grassland and higher summits and plateaux of blanket bog are grazed by hardy upland sheep. • Pastures and hay meadows in the dales are bounded by dry stone walls, which give way to hedgerows in the lower dale. • Tree cover is sparse in the upper and middle dale. Hedgerow and field trees and tree-lined watercourses are common in the lower dale. • Woodland cover is low. Upland ash and oak-birch woods are found in river gorges and dale side gills, and larger conifer plantations in the moorland fringes. • The settled dales contain small villages and scattered farms. Buildings have a strong vernacular character and are built of local stone with roofs of stone flag or slate. • The landscape is scarred in places by mineral workings with many active and abandoned limestone and whinstone quarries and the relics of widespread lead workings. • An open landscape, broad in scale, with panoramic views from higher ground to distant ridges and summits. • The landscape of the moors is remote, natural and elemental with few man made features and a near wilderness quality in places. -

Of St Cuthbert'

A Literary Pilgrimage of Durham by Ruth Robson of St Cuthbert' 1. Market Place Welcome to A Literary Pilgrimage of Durham, part of Durham Book Festival, produced by New Writing North, the regional writing development agency for the North of England. Durham Book Festival was established in the 1980s and is one of the country’s first literary festivals. The County and City of Durham have been much written about, being the birthplace, residence, and inspiration for many writers of both fact, fiction, and poetry. Before we delve into stories of scribes, poets, academia, prize-winning authors, political discourse, and folklore passed down through generations, we need to know why the city is here. Durham is a place steeped in history, with evidence of a pre-Roman settlement on the edge of the city at Maiden Castle. Its origins as we know it today start with the arrival of the community of St Cuthbert in the year 995 and the building of the white church at the top of the hill in the centre of the city. This Anglo-Saxon structure was a precursor to today’s cathedral, built by the Normans after the 1066 invasion. It houses both the shrine of St Cuthbert and the tomb of the Venerable Bede, and forms the Durham UNESCO World Heritage Site along with Durham Castle and other buildings, and their setting. The early civic history of Durham is tied to the role of its Bishops, known as the Prince Bishops. The Bishopric of Durham held unique powers in England, as this quote from the steward of Anthony Bek, Bishop of Durham from 1284-1311, illustrates: ‘There are two kings in England, namely the Lord King of England, wearing a crown in sign of his regality and the Lord Bishop of Durham wearing a mitre in place of a crown, in sign of his regality in the diocese of Durham.’ The area from the River Tees south of Durham to the River Tweed, which for the most part forms the border between England and Scotland, was semi-independent of England for centuries, ruled in part by the Bishop of Durham and in part by the Earl of Northumberland. -

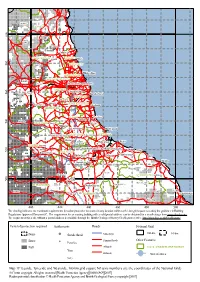

Map 19 Teeside, Tyneside and Wearside, 100-Km Grid Square NZ (Axis Numbers Are the Coordinates of the National Grid) © Crown Copyright

Alwinton ALNWICK 0 0 6 Elsdon Stanton Morpeth CASTLE MORPETH Whalton WANSBECK Blyth 0 8 5 Kirkheaton BLYTH VALLEY Whitley Bay NORTH TYNESIDE NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE Acomb Newton Newcastle upon Tyne 0 GATESHEAD 6 Dye House Gateshead 5 Slaley Sunderland SUNDERLAND Stanley Consett Edmundbyers CHESTER-LE-STREET Seaham DERWENTSIDE DURHAM Peterlee 0 Thornley 4 Westgate 5 WEAR VALLEY Thornley Wingate Willington Spennymoor Trimdon Hartlepool Bishop Auckland SEDGEFIELD Sedgefield HARTLEPOOL Holwick Shildon Billingham Redcar Newton Aycliffe TEESDALE Kinninvie 0 Stockton-on-Tees Middlesbrough 2 Skelton 5 Loftus DARLINGTON Barnard Castle Guisborough Darlington Eston Ellerby Gilmonby Yarm Whitby Hurworth-on-Tees Stokesley Gayles Hornby Westerdale Faceby Langthwaite Richmond SCARBOROUGH Goathland 0 0 5 Catterick Rosedale Abbey Fangdale Beck RICHMONDSHIRE Hornby Northallerton Leyburn Hawes Lockton Scalby Bedale HAMBLETON Scarborough Pickering Thirsk 400 420 440 460 480 500 The shading indicates the maximum requirements for radon protective measures in any location within each 1-km grid square to satisfy the guidance in Building Regulations Approved Document C. The requirement for an existing building with a valid postal address can be obtained for a small charge from www.ukradon.org. The requirement for a site without a postal address is available through the British Geological Survey GeoReports service, http://shop.bgs.ac.uk/GeoReports/. Level of protection required Settlements Roads National Grid None Sunderland Motorways 100-km 10-km Basic Primary Roads Other Features Peterlee Full A Roads LOCAL ADMINISTRATIVE DISTRICT Yarm B Roads Water features Slaley Map 19 Teeside, Tyneside and Wearside, 100-km grid square NZ (axis numbers are the coordinates of the National Grid) © Crown copyright. -

The Commemoration of Founders and Benefactors at the Heart of Durham: City, County and Region

The Commemoration of Founders and Benefactors at the heart of Durham: City, County and Region Address: Professor Stuart Corbridge Vice-Chancellor University of Durham Sunday 22 November 2020 3.30 p.m. VOLUMUS PRÆTEREA UT EXEQUIÆ SINGULIS ANNIS PERPETUIS TEMPORIBUS IN ECCLESIA DUNELMENSI, CONVOCATIS AD EAS DECANO OMNIBUS CANONICIS ET CÆTERIS MINISTRIS SCHOLARIBUS ET PAUPERIBUS, PRO ANIMABUS CHARISSIMORUM PROGENITORUM NOSTRORUM ET OMNIUM ANTIQUI CŒNOBII DUNELMENSIS FUNDATORUM ET BENEFACTORUM, VICESIMO SEPTIMO DIE JANUARII CUM MISSÂ IN CRASTINO SOLENNITER CELEBRENTUR. Moreover it is our will that each year for all time in the cathedral church of Durham on the twenty-seventh day of January, solemn rites of the dead shall be held, together with mass on the following day, for the souls of our dearest ancestors and of all the founders and benefactors of the ancient convent of Durham, to which shall be summoned the dean, all the canons, and the rest of the ministers, scholars and poor men. Cap. 34 of Queen Mary’s Statutes of Durham Cathedral, 1554 Translated by Canon Dr David Hunt, March 2014 2 Welcome Welcome to the annual commemoration of Founders and Benefactors. This service gives us an opportunity to celebrate those whose generosity in the past has enriched the lives of Durham’s great institutions today and to look forward to a future that is full of opportunity. On 27 January 1914, the then Dean, Herbert Hensley Henson, revived the Commemoration of Founders and Benefactors. It had been written into the Cathedral Statutes of 1554 but for whatever reason had not been observed for centuries. -

RSCM Honorary Awards 1936-2020 Hon

FRSCM (220) ARSCM (196) Hon. Life RSCM (62) RSCM Honorary Awards 1936-2020 Hon. RSCM (111) Cert. Special Service (193) Total 782 Award Year Name Dates Position FRSCM 1936 Sir Arthur Somervell 1863-1937 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Chairman of Council SECM FRSCM 1936 Sir Stanley Robert Marchant 1883-1949 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Principal of the Royal Academy of College FRSCM 1936 Sir Walter Galpin Alcock 1861-1947 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Organist of Salisbury Cathedral FRSCM 1936 Sir Edward Bairstow 1874-1946 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Organist of York Minster FRSCM 1936 Sir Hugh Percy Allen 1869-1946 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Director of the Royal College of Music FRSCM 1936 The Revd Dr.Edmund Horace Fellowes 1870-1951 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Choirmaster of St George's, Windsor and Musicologist FRSCM 1936 Sir Henry Walford Davies 1869-1941 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Organist of the Temple Church FRSCM (i) 1936 Dr Henry George Ley 1887-1962 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Precentor of Eton FRSCM (i) 1936 Sir Ivor Algernon Atkins 1869-1953 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Organist of Worcester Cathedral FRSCM (i) 1936 Sir Ernest Bullock 1890-1979 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1936. Organist of Westminster Abbey FRSCM (iii) 1937 Sir William Harris 1883-1973 A Fellow of the College of St Nicolas in 1937. -

County Durham Settlement Study September 2017 Planning the Future of County Durham 1 Context

County Durham Plan Settlement Study June 2018 Contents 1. CONTEXT 2 2. METHODOLOGY 3 3. SCORING MATRIX 4 4. SETTLEMENTS 8 County Durham Settlement Study September 2017 Planning the future of County Durham 1 Context 1 Context County Durham has a population of 224,000 households (Census 2011) and covers an area of 222,600 hectares. The County stretches from the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in the west to the North Sea Heritage Coast in the east and borders Gateshead and Sunderland, Northumberland, Cumbria and Hartlepool, Stockton, Darlington and North Yorkshire. Although commonly regarded as a predominantly rural area, the County varies in character from remote and sparsely populated areas in the west, to the former coalfield communities in the centre and east, where 90% of the population lives east of the A68 road in around half of the County by area. The Settlement Study 2017 seeks to provide an understanding of the number and range of services available within each of the 230 settlements within County Durham. (a) Identifying the number and range of services and facilities available within a settlement is useful context to inform decision making both for planning applications and policy formulation. The range and number of services within a settlement is usually, but not always, proportionate to the size of its population. The services within a settlement will generally determine a settlement's role and sphere of influence. This baseline position provides one aspect for considering sustainability and should be used alongside other relevant, local circumstances. County Durham a 307 Settlements if you exclude clustering 2 Planning the future of County Durham County Durham Settlement Study September 2017 Methodology 2 2 Methodology This Settlement Study updates the versions published in 2009 and 2012 and an updated methodology has been produced following consultation in 2016. -

Cambridge University Reporter Special No 3

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY REPORTER S PECIAL N O 3 M O N D AY 6 N OVE M BER 2017 VOL C X LV I I I ROLL OF THE REGENT HOUSE AND LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE FACULTIES Roll of the Regent House: Promulgation 1 List of Members of the Faculties: Promulgation 51 Architecture and History of Art 51 Engineering 67 Asian and Middle Eastern Studies 51 English 70 Biology 52 History 71 Business and Management 55 Human, Social, and Political Science 73 Classics 56 Law 75 Clinical Medicine 57 Mathematics 76 Computer Science and Technology 62 Modern and Medieval Languages 78 Divinity 63 Music 79 Earth Sciences and Geography 64 Philosophy 79 Economics 65 Physics and Chemistry 80 Education 66 Veterinary Medicine 83 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ii CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY REPORTER [S PECIAL N O . 3 Colleges are indicated by the following abbreviations: Christ’s CHR Homerton HO Queens’ Q Churchill CHU Hughes Hall HH Robinson R Clare CL Jesus JE St Catharine’s CTH Clare Hall CLH King’s K St Edmund’s ED Corpus Christi CC Lucy Cavendish LC St John’s JN Darwin DAR Magdalene M Selwyn SE Downing DOW Murray Edwards MUR Sidney Sussex SID Emmanuel EM Newnham N Trinity T Fitzwilliam F Pembroke PEM Trinity Hall TH Girton G Peterhouse PET Wolfson W Gonville and Caius CAI © 2017 The Chancellor, Masters, and Scholars of the University of Cambridge. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the University of Cambridge, or as expressly permitted by law.