Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

LCSH Section J

J (Computer program language) J. I. Case tractors Thurmond Dam (S.C.) BT Object-oriented programming languages USE Case tractors BT Dams—South Carolina J (Locomotive) (Not Subd Geog) J.J. Glessner House (Chicago, Ill.) J. Strom Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) BT Locomotives USE Glessner House (Chicago, Ill.) UF Clark Hill Lake (Ga. and S.C.) [Former J & R Landfill (Ill.) J.J. "Jake" Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) heading] UF J and R Landfill (Ill.) UF "Jake" Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) Clark Hill Reservoir (Ga. and S.C.) J&R Landfill (Ill.) Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) Clarks Hill Reservoir (Ga. and S.C.) BT Sanitary landfills—Illinois BT Public buildings—Texas Strom Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) J. & W. Seligman and Company Building (New York, J. James Exon Federal Bureau of Investigation Building Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) N.Y.) (Omaha, Neb.) BT Lakes—Georgia USE Banca Commerciale Italiana Building (New UF Exon Federal Bureau of Investigation Building Lakes—South Carolina York, N.Y.) (Omaha, Neb.) Reservoirs—Georgia J 29 (Jet fighter plane) BT Public buildings—Nebraska Reservoirs—South Carolina USE Saab 29 (Jet fighter plane) J. Kenneth Robinson Postal Building (Winchester, Va.) J.T. Berry Site (Mass.) J.A. Ranch (Tex.) UF Robinson Postal Building (Winchester, Va.) UF Berry Site (Mass.) BT Ranches—Texas BT Post office buildings—Virginia BT Massachusetts—Antiquities J. Alfred Prufrock (Fictitious character) J.L. Dawkins Post Office Building (Fayetteville, N.C.) J.T. Nickel Family Nature and Wildlife Preserve (Okla.) USE Prufrock, J. Alfred (Fictitious character) UF Dawkins Post Office Building (Fayetteville, UF J.T. -

Packing for an Adventure at Timberlake

PACKING FOR AN ADVENTURE AT TIMBERLAKE Choose your vessel! Trunks are good for staying organized and have nostalgic charm. However, they do not ship well and cannot be taken on the bus from NYC. If you choose to bring up a trunk in your car, just make sure it is no more than 19" tall so that it fits under the bunk. Duffel Bags are a good alternative. Label Everything I figure each camper brings about 200 items, so that's over 20,000 items to be misplaced and mixed up at camp. If it's labeled, we can return it. We provide laundry service every 7-10 days Each camper can contribute clothes to the “cabin” bag to be sent away to be cleaned and dried at a local facility. Simple Living Think practicality, comfort, and affordability. Please let us know if you need support in borrowing any clothing or equipment before buying things brand new. Sleeping pads, hiking backpacks are all items we can loan out. We encourage kids to explore at camp which often means getting dirty and wearing practical clothes. Check out some cabin and toilet pictures at the end of this document. Clothing □ 7-9 pairs of underwear □ 6-9 pairs of regular socks (cotton or some other suitable material). Lightweight wool socks can be worn several days in a row, retain less odor and keep you warm when they are wet. □ 2 pairs of hiking socks to be worn with boots (allow for some shrinkage when they are washed and dried) □ 1 pairs of long underwear (separate top and bottom) made of polypro, wool or fleece/capilene….not cotton □ 1-2 long-sleeved shirts □ 2-4 pairs of shorts, at least one of which should be made of non-cotton material, loose fitting and cut above the knee, for hiking □ 2-3 pairs of long pants or jeans, at least one pair of which should be non-cotton. -

Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By

Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Japanese Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair Professor Alan Tansman Professor Beate Fricke Summer 2018 © 2018 Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe All Rights Reserved Abstract Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature by Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair My dissertation investigates the role of images in shaping literary production in Japan from the 1880’s to the 1930’s as writers negotiated shifting relationships of text and image in the literary and visual arts. Throughout the Edo period (1603-1868), works of fiction were liberally illustrated with woodblock printed images, which, especially towards the mid-19th century, had become an essential component of most popular literature in Japan. With the opening of Japan’s borders in the Meiji period (1868-1912), writers who had grown up reading illustrated fiction were exposed to foreign works of literature that largely eschewed the use of illustration as a medium for storytelling, in turn leading them to reevaluate the role of image in their own literary tradition. As authors endeavored to produce a purely text-based form of fiction, modeled in part on the European novel, they began to reject the inclusion of images in their own work. -

The Making of an American Shinto Community

THE MAKING OF AN AMERICAN SHINTO COMMUNITY By SARAH SPAID ISHIDA A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2007 Sarah Spaid Ishida 2 To my brother, Travis 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many people assisted in the production of this project. I would like to express my thanks to the many wonderful professors who I have learned from both at Wittenberg University and at the University of Florida, specifically the members of my thesis committee, Dr. Mario Poceski and Dr. Jason Neelis. For their time, advice and assistance, I would like to thank Dr. Travis Smith, Dr. Manuel Vásquez, Eleanor Finnegan, and Phillip Green. I would also like to thank Annie Newman for her continued help and efforts, David Hickey who assisted me in my research, and Paul Gomes III of the University of Hawai’i for volunteering his research to me. Additionally I want to thank all of my friends at the University of Florida and my husband, Kyohei, for their companionship, understanding, and late-night counseling. Lastly and most importantly, I would like to extend a sincere thanks to the Shinto community of the Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America and Reverend Koichi Barrish. Without them, this would not have been possible. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 ABSTRACT.....................................................................................................................................7 -

Zen Classics: Formative Texts in the History of Zen Buddhism

Zen Classics: Formative Texts in the History of Zen Buddhism STEVEN HEINE DALE S. WRIGHT, Editors OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Zen Classics This page intentionally left blank Zen Classics Formative Texts in the History of Zen Buddhism edited by steven heine and dale s. wright 1 2006 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright ᭧ 2006 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Zen classics: formative texts in the history of Zen Buddhism / edited by Steven Heine and Dale S. Wright. p. cm Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: The concept of classic literature in Zen Buddhism / Dale S. Wright—Guishan jingce and the ethical foundations of Chan practice / Mario Poceski—A Korean contribution to the Zen canon the Oga hae scorui / Charles Muller—Zen Buddhism as the ideology of the Japanese state / Albert Welter—An analysis of Dogen’s Eihei goroku / Steven Heine—“Rules of purity” in Japanese Zen / T. -

Sourdough Manual "Winter Is Here" Klondike Derby 2020 March 6-8, 2020 Hosted by Talako Lodge

Sourdough Manual "Winter Is Here" Klondike Derby 2020 March 6-8, 2020 Hosted by Talako Lodge Camp Marin Sierra Marin Council, B.S.A. Table of Contents Information about Klondike .............................................................................. 1 Winter at Marin Sierra ......................................................................................... 2 Staying Warm ....................................................................................................... 4 Cold Weather Safety ........................................................................................... 9 Snowshoes .......................................................................................................... 11 Klondike Derby Sleds........................................................................................ 12 Snow Shelters .................................................................................................... 13 1 Information about Klondike 2020 Competition Equipment Each patrol competing should have the following equipment. This list is not final; Talako Lodge may change or add to this list at any time. Refer to the event descriptions to determine what else you might need. Items should be marked with your troop number. Patrol flag and yell Scout handbook Rope 6 foot poles or staves Shovel or trowel Firewood Tinder Matches Compass First aid kit Large tarp Klondike sled (see design on page 12) 2 Winter at Marin Sierra Water Supply The winter water supply at Marin Sierra is limited, and we’re not yet sure if -

Türkçe-Japonca Sözlük

Japonca Türkçe - Türkçe-Japonca Sözlük www.kitapsevenler.com Merhabalar %XUD\D<NOHGL÷LPL]H-kitaplar *|UPHHQJHOOLOHULQRNX\DELOHFH÷LIRUPDWODUGDKD]ÕUODQPÕúWÕU Buradaki E-.LWDSODUÕYHGDKDSHNoRNNRQXGDNL.LWDSODUÕELOKDVVDJ|UPHHQJHOOL DUNDGDúODUÕQLVWLIDGHVLQHVXQX\RUX] %HQGHELUJ|UPHHQJHOOLRODUDNNLWDSRNXPD\ÕVHYL\RUXP (NUDQRNX\XFXSURJUDPNRQXúDQ%UDLOOH1RW6SHDNFLKD]ÕNDEDUWPDHNUDQYHEHQ]HUL \DUGÕPFÕDUDoODU VD\HVLQGHEXNLWDSODUÕRNX\DELOL\RUX]%LOJLQLQSD\ODúÕOGÕNoDSHNLúHFH÷LQHLQDQÕ\RUXP Siteye yüklenen e-NLWDSODUDúD÷ÕGDDGÕJHoHQNDQXQDLVWLQDGHQWP NLWDSVHYHUDUNDGDúODULoLQKD]ÕUODQPÕúWÕU $PDFÕPÕ]\D\ÕQHYOHULQH]DUDUYHUPHN\DGDHVHUOHUGHQPHQIDDWWHPLQHWPHNGH÷LOGLUHOEHWWH Bu e-kitaplar normal kitapODUÕQ\HULQLWXWPD\DFD÷ÕQGDQNLWDSODUÕEH÷HQLSWHHQJHOOLROPD\DQ okurlar, NLWDSKDNNÕQGDILNLUVDKLELROGXNODUÕQGDLQGLUGLNOHULNLWDSWDDGÕJHoHQ \D\ÕQHYLVDKDIODUNWSKDQHYHNLWDSoÕODUGDQLOJLOLNLWDEÕWHPLQHGHELOLUOHU Bu site tamamen ücretsizdir YHVLWHQLQLoHUL÷LQGHVXQXOPXúRODQNLWDSODU KLoELUPDGGLoÕNDUJ|]HWLOPHNVL]LQWPNLWDSGRVWODUÕQÕQLVWLIDGHVLQHVXQXOPXúWXU Bu e-NLWDSODUNDQXQHQKLoELUúHNLOGHWLFDULDPDoODNXOODQÕODPD]YHNXOODQGÕUÕODPD] %LOJL3D\ODúPDNODdR÷DOÕU <DúDU087/8 øOJLOL.DQXQ6D\ÕOÕ.DQXQXQDOWÕQFÕ%|OP-dHúLWOL+NPOHUE|OPQGH\HUDODQ "EK MADDE 11. -'HUVNLWDSODUÕGDKLODOHQLOHúPLúYH\D\D\ÕPODQPÕú\D]ÕOÕLOLP YHHGHEL\DWHVHUOHULQLQHQJHOOLOHULoLQUHWLOPLúELUQVKDVÕ\RNVDKLoELUWLFDUvDPDo güdülmekVL]LQELUHQJHOOLQLQNXOODQÕPÕLoLQNHQGLVLYH\DoQF ELUNLúLWHNQVKDRODUDN\DGDHQJHOOLOHUH\|QHOLNKL]PHWYHUHQH÷LWLPNXUXPXYDNÕIYH\D GHUQHNJLELNXUXOXúODUWDUDIÕQGDQLKWL\DoNDGDUNDVHW&'EUDLOO DOIDEHVLYHEHQ]HULIRUPDWODUGDoR÷DOWÕOPDVÕYH\D|GQoYHULOPHVLEX.DQXQGD|QJ|UOHQ -

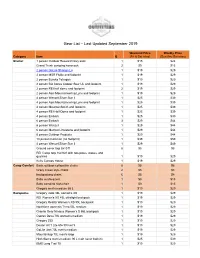

Gear List 09-2019

Gear List – Last Updated September 2019 Weekend Price Weekly Price Category Item Q (Fri & Sat nites) (Sun thru Sat nites) Shelter 1 person Outdoor Research bivy sack 1 $15 $24 Grand Trunk campinG hammock 2 $9 $15 2 person GoLite ShanGri-La 1 $19 $29 2 person MSR Flylite and footprint 1 $19 $29 2 person Eureka TetraGon 1 $19 $29 2 person BiG AGnes Copper Spur UL and footprint 1 $19 $29 2 person REI half dome and footprint 2 $19 $29 2 person Alps MountaineerinG Lynx and footprint 1 $19 $29 4 person Wenzel Silver Star II 1 $25 $39 4 person Alps MountaineerinG Lynx and footprint 1 $25 $39 4 person MountainSmith and footprint 1 $25 $39 4 person REI Half Dome and footprint 1 $25 $39 4 person Embark 1 $25 $39 6 person Embark 3 $29 $44 6 person Wenzel 1 $29 $44 6 person Marmot Limestone and footprint 1 $29 $44 6 person Outdoor Products 1 $29 $44 10 person Coleman (no footprint) 1 $39 $59 4 person Wenzel Silver Star II 1 $29 $49 Ground cover tarp 8x10 ft 8 $5 $8 REI Camp tarp 16x16 ft with two poles, stakes, and Guylines 1 $19 $29 Kelty Canopy House 1 $19 $29 Camp Comfort Basic outdoor collapsible chairs 8 $5 $8 Crazy Creek style chairs 2 $5 $8 backpackinG chairs 6 $5 $8 Baby sun/buG tent 1 $9 $15 Baby campinG hiGh-chair 1 $9 $15 GreGory men's medium 65 L 1 $19 $29 Backpacks GreGory Jade 38L women's XS 1 $19 $29 REI Women's XS 45L ultraliGht backpack 1 $19 $29 GreGory Reality Women's XS 55L backpack 1 $19 $29 Northface women's Terra 55L medium 1 $19 $29 Granite Gear Nimbus Women's S 55L backpack 1 $19 $29 Osprey Deva 70L women's medium 1 $19 $29 -

Glimpses of an Unfamiliar Japan (4000 Word Level)

GLIMPSES OF UNFAMILIAR JAPAN First Series by LAFCADIO HEARN This book, Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan, is a Mid-Frequency Reader and has been adapted to suit readers with a vocabulary of 4,000 words. It is just under 100,000 words long. It is available in three versions of different difficulty. This version is adapted from the Project Gutenberg E-text (http://www.pgdp.net/). In this book, the adaptation involved replacing 1,196 different words. There are 377 words at the 5th 1000 level, 55 words at the 6th 1000 level and 185 words beyond that, totalling 617 target words. The words from the 6th 1000 on each occur often in the text, typically more than 10 times. The book also contains 590 different Japanese words which are explained in the text. It was adapted by Paul Nation. Dedication TO THE FRIENDS WHOSE KINDNESS ALONE RENDERED POSSIBLE MY STAY IN THE ORIENT, PAYMASTER MITCHELL McDONALD, U.S.N. AND BASIL HALL CHAMBERLAIN, ESQ. Emeritus Professor of Philology and Japanese in the Imperial University of Tokyo I DEDICATE THESE VOLUMES IN TOKEN OF AFFECTION AND GRATITUDE. CONTENTS PREFACE 1 MY FIRST DAY IN THE ORIENT 2 THE WRITING OF KOBODAISHI 3 JIZO 4 A PILGRIMAGE TO ENOSHIMA 5 AT THE MARKET OF THE DEAD 6 BON-ODORI 7 THE CHIEF CITY OF THE PROVINCE OF THE GODS 8 KITZUKI: THE MOST ANCIENT SHRINE IN JAPAN 9 IN THE CAVE OF THE CHILDREN'S GHOSTS 10 AT MIONOSEKI 11 NOTES ON KITZUKI 12 AT HINOMISAKI 13 SHINJU 14 YAEGAKI-JINJA 15 KITSUNE PREFACE In the Introduction to his charming Tales of Old Japan, Mr. -

Program 1..154

The 97th Annual Meeting of CSJ Program Chair: INOUE, Haruo(15:30~15:55) Room S1 1S1- 15 Medium and Long-Term Program Lecture Artificial Photosynthesis of Ammonia(RIES, Hokkaido Univ.)○MISAWA, Hiroaki (15:30~15:55) Fourth Building, Section B J11 Chair: INOUE, Haruo(15:55~16:20) 1S1- 16 Medium and Long-Term Program Lecture Mechanism of water-splitting by photosystem II using the energy of visible light(Grad. Sustainable and Functional Redox Chemistry Sch. Nat. Sci. Technol., Okayama Univ.)○SHEN, Jian-ren(15:55~ ) Thursday, March 16, AM 16:20 (9:30 ~9:35 ) Chair: TAMIAKI, Hitoshi(16:20~16:45) 1S1- 01 Special Program Lecture Opening Remarks(Sch. Mater. & 1S1- 17 Medium and Long-Term Program Lecture Excited State Chem. Tech., Tokyo Tech.)○INAGI, Shinsuke(09:30~09:35) Molecular Dynamics of Natural and Artificial Photosynthesis(Sch. Sci. Tech., Kwansei Gakuin Univ.)○HASHIMOTO, Hideki(16:20~16:45) Chair: ATOBE, Mahito(9:35 ~10:50) 1S1- 02 Special Program Lecture Polymer Redox Chemistry toward Chair: ISHITANI, Osamu(16:45~17:10) Functional Materials(Sch. Mater. & Chem. Tech., Tokyo Tech.)○INAGI, 1S1- 18 Medium and Long-Term Program Lecture Recent pro- Shinsuke(09:35~09:50) gress on artificial photosynthesis system based on semiconductor photocata- 1S1- 03 Special Program Lecture Organic Redox Chemistry Enables lysts(Grad. Sch. Eng., Kyoto Univ.)○ABE, Ryu(16:45~17:10) Automated Solution-Phase Synthesis of Oligosaccharides(Grad. Sch. Eng., Tottori Univ.)○NOKAMI, Toshiki(09:50~10:10) (17:10~17:20) 1S1- 04 Special Program Lecture Redox Regulation of Functional 1S1- 19 Medium and Long-Term Program Lecture Closing re- Dyes and Their Applications to Optoelectronic Devices(Fac. -

Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan

Soto Zen in Medieval Japan Kuroda Institute Studies in East Asian Buddhism Studies in Ch ’an and Hua-yen Robert M. Gimello and Peter N. Gregory Dogen Studies William R. LaFleur The Northern School and the Formation of Early Ch ’an Buddhism John R. McRae Traditions of Meditation in Chinese Buddhism Peter N. Gregory Sudden and Gradual: Approaches to Enlightenment in Chinese Thought Peter N. Gregory Buddhist Hermeneutics Donald S. Lopez, Jr. Paths to Liberation: The Marga and Its Transformations in Buddhist Thought Robert E. Buswell, Jr., and Robert M. Gimello Studies in East Asian Buddhism $ Soto Zen in Medieval Japan William M. Bodiford A Kuroda Institute Book University of Hawaii Press • Honolulu © 1993 Kuroda Institute All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 93 94 95 96 97 98 5 4 3 2 1 The Kuroda Institute for the Study of Buddhism and Human Values is a nonprofit, educational corporation, founded in 1976. One of its primary objectives is to promote scholarship on the historical, philosophical, and cultural ramifications of Buddhism. In association with the University of Hawaii Press, the Institute also publishes Classics in East Asian Buddhism, a series devoted to the translation of significant texts in the East Asian Buddhist tradition. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bodiford, William M. 1955- Sotd Zen in medieval Japan / William M. Bodiford. p. cm.—(Studies in East Asian Buddhism ; 8) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-8248-1482-7 l.Sotoshu—History. I. Title. II. Series. BQ9412.6.B63 1993 294.3’927—dc20 92-37843 CIP University of Hawaii Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources Designed by Kenneth Miyamoto For B.