Outré Aesthetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report Resumes

REPORT RESUMES ED 019 218 88 SE 004 494 A RESOURCE BOOK OF AEROSPACE ACTIVITIES, K-6. LINCOLN PUBLIC SCHOOLS, NEBR. PUB DATE 67 EDRS PRICEMF.41.00 HC-S10.48 260P. DESCRIPTORS- *ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SCIENCE, *PHYSICAL SCIENCES, *TEACHING GUIDES, *SECONDARY SCHOOL SCIENCE, *SCIENCE ACTIVITIES, ASTRONOMY, BIOGRAPHIES, BIBLIOGRAPHIES, FILMS, FILMSTRIPS, FIELD TRIPS, SCIENCE HISTORY, VOCABULARY, THIS RESOURCE BOOK OF ACTIVITIES WAS WRITTEN FOR TEACHERS OF GRADES K-6, TO HELP THEM INTEGRATE AEROSPACE SCIENCE WITH THE REGULAR LEARNING EXPERIENCES OF THE CLASSROOM. SUGGESTIONS ARE MADE FOR INTRODUCING AEROSPACE CONCEPTS INTO THE VARIOUS SUBJECT FIELDS SUCH AS LANGUAGE ARTS, MATHEMATICS, PHYSICAL EDUCATION, SOCIAL STUDIES, AND OTHERS. SUBJECT CATEGORIES ARE (1) DEVELOPMENT OF FLIGHT, (2) PIONEERS OF THE AIR (BIOGRAPHY),(3) ARTIFICIAL SATELLITES AND SPACE PROBES,(4) MANNED SPACE FLIGHT,(5) THE VASTNESS OF SPACE, AND (6) FUTURE SPACE VENTURES. SUGGESTIONS ARE MADE THROUGHOUT FOR USING THE MATERIAL AND THEMES FOR DEVELOPING INTEREST IN THE REGULAR LEARNING EXPERIENCES BY INVOLVING STUDENTS IN AEROSPACE ACTIVITIES. INCLUDED ARE LISTS OF SOURCES OF INFORMATION SUCH AS (1) BOOKS,(2) PAMPHLETS, (3) FILMS,(4) FILMSTRIPS,(5) MAGAZINE ARTICLES,(6) CHARTS, AND (7) MODELS. GRADE LEVEL APPROPRIATENESS OF THESE MATERIALSIS INDICATED. (DH) 4:14.1,-) 1783 1490 ,r- 6e tt*.___.Vhf 1842 1869 LINCOLN PUBLICSCHOOLS A RESOURCEBOOK OF AEROSPACEACTIVITIES U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION K-6) THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. 1919 O O Vj A PROJECT FUNDED UNDER TITLE HIELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION ACT A RESOURCE BOOK OF AEROSPACE ACTIVITIES (K-6) The work presentedor reported herein was performed pursuant to a Grant from the U. -

EPSC-DPS2011-1845, 2011 EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2011 C Author(S) 2011

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 6, EPSC-DPS2011-1845, 2011 EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2011 c Author(s) 2011 Analysis of mineralogy of an effusive volcanic lunar dome in Marius Hills, Oceanus Procellarum. A.S. Arya, Guneshwar Thangjam, R.P. Rajasekhar, Ajai Space Applications Centre, Indian Space Research Organization, Ahmedabad-380 015 (India). Email:[email protected] Abstract found on the lunar surface. As a part of initiation of the study of mineralogy of MHC, an effusive dome Domes are analogous to the terrestrial shield located in the south of Rima Galilaei, near the volcanoes and are among the important volcanic contact of Imbrian and Eratosthenian geological units features found on the lunar surface indicative of is taken up for the present study. The morphology, effusive vents of primary volcanism within Mare rheology and the possible dike parameters have regions. Marius Hills Complex (MHC) is one of the already been studied and reported [5]. most important regions on the entire lunar surface, having a complex geological setting and largest distribution of volcanic constructs with an abundant number of volcanic features like domes, cones and rilles. The mineralogical study of an effusive dome located in the south of Rima Galilaei, near the contact of Imbrian and Eratosthenian geological units is done using hyperspectral band parameters and spectral plots so as to understand the compositional variation, the nature of the volcanism and relate it to the rheology of the dome. Fig. 1: Distribution of dome in MHC (Red-the dome under study, Green- from Virtual Moon Atlas, Magenta [6]) and the Study area showing the dome under study on M3 1. -

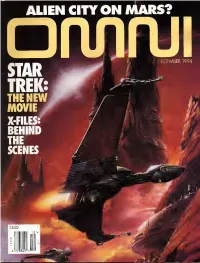

OMNI Magazine Interview, July 1992)

ALIEN CITY ON MARS? TiTil W i^ -A Im; SCENES Lji U *' Ul EDITOR IN CHIEF & DESIGN DIRECTOR: BOB GUCCIONE PRESIDENT a C.O.O.: KATHY KEETON VP/EDITOR' KEITH FERRELL EXECUTIVE VP/GBAPHICS DIRECTOR- FRANK DEVINO MANAGING EDITOR: CAROLINE DARK ART DIRECTOR: CATHRYN MEZZO First Word Continuum By Dana Rohrabacher 42 Fighting for Opening the X-Files U.S. patent rights By David Bischoff S Mulder and Scully know Communications something is m out there—and so do their Funds many fans. A behind- By Linda Marsa the-scenes lool< at this fas- Cashing in on collectibles cinating and m increasingly popular Electronic Universe new show. By Grsgg Keizer ArchiTreIc Medicine Designing Generations By Anita Bartholomew By Herman Zimmerman m and Philip Thomas Edgerly .Sounds Boldly going where By Steve Nadis few. production designers Sounds of the silent have gone before: 22 designing the Star Trek Eanii By Melanie Menagh Choices Fiction: S.4 Dying Virtual Realities [Vlichael IVlarshall Smith By Tom Dworetzl<y 7^ 23 Cartoon Feature Artificial Intelligence . By Steve Nadis Interview: 32 Richard hioa gland Mind By Steve Nadis By Steve Nadis A close-up lool< at the Hallucinations, man behind delusions, the face on Mars and schizophrenia SS 33 Tsuneo Sanda's cover painting, On Patrol, made possible by Antimatter the PI" I p Edge ly Age cy n a'^sar qt on witi ZD^sgn Copyrght Pa amount PcturesCorporaticn Games (Additional art rred t"^ page 110) By bi, iff Morris SR1''6ril7'iBn FIRST UUORD INVENTING AMERICA: Patent laws and the protection of individual rights By Dana Rohrabacher merica's greatest asset side. -

Giant List of Folklore Stories Vol. 5: the United States

The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay Skim and Scan The Giant List of Folklore Stories Folklore, Folktales, Folk Heroes, Tall Tales, Fairy Tales, Hero Tales, Animal Tales, Fables, Myths, and Legends. Vol. 5: The United States Presented by Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The fastest, most effective way to teach students organized multi-paragraph essay writing… Guaranteed! Beginning Writers Struggling Writers Remediation Review 1 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay – Guaranteed Fast and Effective! © 2018 The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The Giant List of Folklore Stories – Vol. 5 This volume is one of six volumes related to this topic: Vol. 1: Europe: South: Greece and Rome Vol. 4: Native American & Indigenous People Vol. 2: Europe: North: Britain, Norse, Ireland, etc. Vol. 5: The United States Vol. 3: The Middle East, Africa, Asia, Slavic, Plants, Vol. 6: Children’s and Animals So… what is this PDF? It’s a huge collection of tables of contents (TOCs). And each table of contents functions as a list of stories, usually placed into helpful categories. Each table of contents functions as both a list and an outline. What’s it for? What’s its purpose? Well, it’s primarily for scholars who want to skim and scan and get an overview of the important stories and the categories of stories that have been passed down through history. Anyone who spends time skimming and scanning these six volumes will walk away with a solid framework for understanding folklore stories. -

A Finding Aid to the Samuel J. Wagstaff Papers, Circa 1932-1985, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Samuel J. Wagstaff Papers, circa 1932-1985, in the Archives of American Art Catherine S. Gaines Funding for the digitization of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art December 13, 2006 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1932-1986.................................................................... 5 Series 2: Writings, 1961-1983................................................................................ 25 Series 3: Miscellaneous Papers and Artifacts, -

Yerba Buena Redivivus 5

YERBA BUENA REDIVIVUS 5. CHIEF WILLIAM FULLER, TuolumneCounty,5/29/1937 "Be it knowne unto all men by these presents WHERAS in the CAPITULUS NO.1 year of grace 1759 the greate Hi-oH of the Mee- Wuks was (Organized 1931) seduced by the Buccaneer Francis Drake to deliver this land of Nova Albion to Elizabeth Ye Queene and her successors (San Francisco, San Mateo, Marin, Sonoma, forever - now therefore I, the present chief & Hi-oH of the Mee- Solano, Lake, and Mendocino Counties) Wuk nation, do now REVOKE said grant on grounds of deceit, fraud, and failure to occupy said domain. Done in the presence of E Clampus Vitus, May 29, 1937 - William Fuller, O.H." (Plaque located near Tuolumne City, at Cherokee Reservation, 1. PANAMINT CITY, Inyo County, 11117/1935 at Indian Roundhouse.) "In memory of the forgotten miner. Dedicated by E Clampus Vitus, November 17, 1935." (Joint with Platrix Chapter No.2.) (Plaque located at site of ghost town of Panamint, attached to wall of Stewart Hunter Mill ruins.) 2. JAMES W. MARSHALL, Sacramento County, 2/22/1936 "JAMES W. MARSHALL on January 28, 1848, here dis- closed to Capt. Sutter his discovery of gold made at Coloma four days before. Placed by E Clampus Vitus, February 22, 1936." (Joint dedication with Platrix Chapter No.2.) (Plaque located at Sutter's Fort, on door of room where James W. Marshall disclosed his discovery to Capt. Sutter.) 3. MOFFAT'S MINT, Mariposa County, 6/1611936 "Here, at California's first mint, octagonal fifty dollar gold slugs were produced under authority of Congress in 1851. -

A Description of the Main Characters in the Movie the Greatest Showman

A DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE MOVIE THE GREATEST SHOWMAN A PAPER BY ELVA RAHMI REG.NO: 152202024 DIPLOMA III ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF CULTURE STUDY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH SUMATERA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I am ELVA RAHMI, declare that I am the sole author of this paper. Except where reference is made in the text of this paper, this paper contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a paper by which I have qualified for or awarded another degree. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of this paper. This paper has not been submitted for the award of another degree in any tertiary education. Signed : ……………. Date : 2018 i UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA COPYRIGHT DECLARATION Name: ELVA RAHMI Title of Paper: A DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE MOVIE THE GREATEST SHOWMAN. Qualification: D-III / Ahli Madya Study Program : English 1. I am willing that my paper should be available for reproduction at the discretion of the Libertarian of the Diploma III English Faculty of Culture Studies University of North Sumatera on the understanding that users are made aware of their obligation under law of the Republic of Indonesia. 2. I am not willing that my papers be made available for reproduction. Signed : ………….. Date : 2018 ii UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA ABSTRACT The title of this paper is DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE GREATEST SHOWMAN MOVIE. The purpose of this paper is to find the main character. -

San Francisco Biography Collection SF BIO COLL

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2489r71w No online items Finding Aid to the San Francisco Biography Collection SF BIO COLL Finding aid prepared by David Krah and California Ephemera Project staff; updated by San Francisco History Center staff. The California Ephemera Project was funded by a Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources in 2009-2010. San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA 94102 [email protected] URL: http://www.sfpl.org/sfhistory 2010, revised January 2020 Finding Aid to the San Francisco SF BIO COLL 1 Biography Collection SF BIO COLL Title: San Francisco Biography Collection Date (inclusive): 1850-present Identifier/Call Number: SF BIO COLL Physical Description: 45 Linear Feet(in 27 file drawers) Contributing Institution: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA 94102 415-557-4567 [email protected] URL: http://sfpl.org/sfhistory Abstract: Consists of a wide variety of materials relating to people widely known and relatively unknown in San Francisco, the greater Bay Area, and California. Includes materials pertaining to: prominent historical San Franciscans such as past mayors, railroad and mining barons and their heirs, early explorers and Gold Rush and Victorian era figures; police and fire chiefs; local and state politicians and judges; architects, especially Victorian era and practioners of the Bay Region style; bishops and pastors; labor leaders; Olympic Club members; artists, artisans, poets, writers, and composers; restaurateurs, hoteliers, merchants and other ordinary citizens; unique San Francisco personalities such as Emperor Norton and Mary Ellen Pleasant. -

Broke but Not Bored in SF

Resources Broke but Not Bored in SF Free fun stuff to do and useful places to go June 21 – June 28 Broke but not Bored in SF is a collage of free activities and events including concerts, films, street festivals, cul- tural events, lectures, workshops, harm reduction groups, community activism opportunities, mindfulness, wellness and fitness resources, and opportunities to see and do art. The San Francisco AIDS Foundation com- piles this calendar. Please send suggestions, additions and/or corrections to [email protected] You can also get added to our distribution list by emailing me. Broke but Not Bored in SF is online (and searchable): https://www.facebook.com/brokebutnotbored/ http://www.stonewallsf.org/ Heads Up – The Pride Parade is June 30, a week from Sunday. If you want to march with one of the organized groups like Openhouse, Lyric, the SF LGBT Center, etc., sign up ASAP via their website. Even if you don’t march, come out to cheer us on. Resources San Francisco Needle Exchange/Syringe Access Schedule (last updated December 6, 2018) Mon 9am-7pm SFAF SAS 117 6th street @ Mission/ 6th Street Harm Reduction Center SOMA/6th Mon Noon-5pm, 7-9pm Glide 330 Ellis btw Jones and Taylor TL Mon Noon -7:30pm SFDUU 149 Turk St. (@Taylor) TL Mon 4-6pm SFAF SAS 3rd Street and Innes Ave. look for white van Bayview Mon 5:30-7:30pm SFNE 558 Clayton St. in the Free Clinic, upstairs Haight Tues 9am-1pm, 4 -7pm SFAF SAS 117 6th street @ Mission/ 6th Street Harm Reduction Center SOMA/6th Tues Noon -7:30pm SFDUU 149 Turk St. -

A Study About a Lunar Dome Near Hortensius: Morphometry and Mode of Formation

47th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2016) 1005.pdf A study about a lunar dome near Hortensius: Morphometry and mode of formation. M. Wirths1, R. Lena2 , A. Mallama3 - Geologic Lunar Research (GLR) Group. 1km 67 Camino Observatorio, Baja California, Mexico; [email protected]; 2 Via Cartesio 144, sc. D, 00137 Rome, Italy; [email protected]; 314012 Lancaster Lane, Bowie, MD, 20715, USA, [email protected] Introduction: Lunar mare domes formed during the later stages of volcanic episode on the Moon, char- acterized by a decreasing rate of lava extrusion and comparably low eruption temperatures, resulted in the formation of effusive domes. Important clusters of lu- nar domes are observed in the Hortensius/Milichius/T. Mayer region in Mare Insularum and in Mare Tranquillitatis around the craters Arago and Cauchy. The region west of Copernicus extending from Hortensius to Milichius and to Tobias Mayer contains large numbers of lunar domes and cones, evidence of past volcanism on the lunar surface [1-3]. A compre- hensive map of the area was produced by GLR group, including the six lunar domes north of Hortensius and three lower domes to the south of Hortensius [4]. Fig. 1. Telescopic image acquired on May 1, 2012, at 03:44 In this contribution we provide an analysis of an- UT with a 450 mm aperture Starmaster driven Dobsonian other low dome to the east of Hortensius, termed H11, (M. Wirths). Morphometric properties of the domes H1-H7 located at 26.87° W and 6.88° N and with a prominent have been examined in previous studies [1, 3]. -

Arlene Gottfried L’Insouciance D’Une Époque

DOSSIER DE PRESSE ARLENE GOTTFRIED L’INSOUCIANCE D’UNE ÉPOQUE 9 JANVIER – 5 MARS 2016 Du mercredi au samedi de 14h à 19h et sur rendez-vous Vernissage le 9 janvier de 14h à 19h ©Arlene Gottfried / Courtesy Les Douches la Galerie Décalé, tendre, libre, intime, joyeux, les qualificatifs ne manquent pas pour résumer ce portrait du New York des années 70-80. Une vie sans contrainte qui nous apparaît à des années lumière de notre quotidien. Ce vent de liberté d’expression avant l’épidémie du sida transparaît dans cette fresque noir et blanc. Nous sommes très heureux d’exposer pour la première fois en France ce travail d’Arlene Gottfried à la galerie. Une grande dame de la photographie qui mérite d’être mieux connue. Commissaires d’exposition : Laurence Cornet et Françoise Morin Contact : Françoise Morin 01 78 94 03 00 - [email protected] ARLENE GOTTFRIED Arlene Gottfried, dont le travail est encore mal connu en France, est avant tout new-yorkaise. Toute son œuvre s’inscrit dans ce monde urbain très spécifique, qui a constamment nourri sa soif d’observation depuis l’enfance. L’exposition organisée aux Douches présente - pour la première fois à Paris – une sélection de photographies de jeunesse, prises dans les années 70 et 80, lorsqu’elle sillonnait sans cesse Brooklyn à la recherche de lieux vivants, de tronches étonnantes, de scènes de rue insolites. C’est une spontanéité détachée d’ambition qui dessine son parcours. Refusant de faire des études, elle a préféré prendre un emploi de bureau pendant la journée et apprendre la photographie en cours du soir. -

3 Blind Moose Bronze 2005 3 Blind Moose Merlot California $9.99

3 Blind Moose Bronze 2005 3 Blind Moose Merlot California $9.99 Silver 2006 3 Blind Moose Chardonnay California $9.99 Silver 2007 3 Blind Moose Pinot Grigio California $9.99 Alexander Valley Vineyards Silver 2004 Cyrus Alexander Valley $55.00 Gold 2005 Syrah Alexander Valley $20.00 Bronze 2005 Cyrus Zinfandel Alexander Valley $35.00 Alice White Bronze 2007 Merlot Southeast Australia $6.99 Bronze 2007 Chardonnay Southeast Australia $6.99 Bronze 2007 Lexia Southeast Australia $6.99 Bronze 2006 Riesling Southeast Australia $6.99 Angel Juice Vineyards Silver 2006 Chardonnay Central Coast $21.99 Angove's Silver 2007 Nine Vines Rose South Australia $10.99 Bronze 2006 Nine Vines Shiraz/Viognier South Australia $10.99 Silver 2005 Red Belly Black Shiraz South Australia $11.99 Gold 2006 Red Belly Black Chardonnay South Australia $11.99 Aquinas Silver 2005 Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley $13.00 Silver 2006 Chardonnay Napa Valley $13.00 Auto Moto Bronze 2005 Auto Moto Merlot California $12.99 Bronze 2007 Auto Moto Riesling California $12.99 Baileyana Winery Silver 2006 Pinot Noir, Grand Firepeak Cuvee Edna Valley $38.00 Gold 2005 Syrah, Grand Firepeak Cuvee Edna Valley $30.00 Silver 2006 Chardonnay, Grand Firepeak Cuvee Edna Valley $30.00 Ballatore Gold NV Gran Spumante California $7.99 Bronze NV Rosso Spumante California $7.99 Barefoot Bubbly Bronze NV Chardonnay Champagne California $9.99 Silver NV Premium Extra Dry California $9.99 Bronze NV White Zinfandel California $9.99 Barefoot Cellars Bronze NV Cabernet Sauvignon California $6.00 Bronze NV