Contact, Crossover, Continuity: the Mee Rgence and Development of the Two Basic Lace Techniques Santina Levey London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEEDLE LACES Battenberg, Point & Reticella Including Princess Lace 3Rd Edition

NEEDLE LACES BATTENBERG, POINT & RETICELLA INCLUDING PRINCESS LACE 3RD EDITION EDITED BY JULES & KAETHE KLIOT LACIS PUBLICATIONS BERKELEY, CA 94703 PREFACE The great and increasing interest felt throughout the country in the subject of LACE MAKING has led to the preparation of the present work. The Editor has drawn freely from all sources of information, and has availed himself of the suggestions of the best lace-makers. The object of this little volume is to afford plain, practical directions by means of which any lady may become possessed of beautiful specimens of Modern Lace Work by a very slight expenditure of time and patience. The moderate cost of materials and the beauty and value of the articles produced are destined to confer on lace making a lasting popularity. from “MANUAL FOR LACE MAKING” 1878 NEEDLE LACES BATTENBERG, POINT & RETICELLA INLUDING PRINCESS LACE True Battenberg lace can be distinguished from the later laces CONTENTS by the buttonholed bars, also called Raleigh bars. The other contemporary forms of tape lace use the Sorrento or twisted thread bar as the connecting element. Renaissance Lace is INTRODUCTION 3 the most common name used to refer to tape lace using these BATTENBERG AND POINT LACE 6 simpler stitches. Stitches 7 Designs 38 The earliest product of machine made lace was tulle or the PRINCESS LACE 44 RETICELLA LACE 46 net which was incorporated in both the appliqued hand BATTENBERG LACE PATTERNS 54 made laces and later the elaborate Leavers laces. It would not be long before the narrow tapes, in fancier versions, would be combined with this tulle to create a popular form INTRODUCTION of tape lace, Princess Lace, which became and remains the present incarnation of Belgian Lace, combining machine This book is a republication of portions of several manuals made tapes and motifs, hand applied to machine made tulle printed between 1878 and 1938 dealing with varieties of and embellished with net embroidery. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 74-6985 SMITH, Anna Laura, 1915- TWENTIETH CENTURY INTERPRETATIONS of the DON JUAN THEME

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

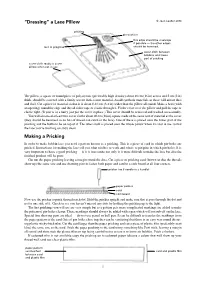

Bobbin Lace You Need a Pattern Known As a Pricking

“Dressing” a Lace Pillow © Jean Leader 2014 pricking pin-cushion this edge should be a selvage if possible — the other edges lace in progress should be hemmed. cover cloth between bobbins and lower part of pricking cover cloth ready to cover pillow when not in use The pillow, a square or round piece of polystyrene (preferably high density) about 40 cm (16 in) across and 5 cm (2 in) thick, should be covered with a firmly woven dark cotton material. Avoid synthetic materials as these will attract dust and fluff. Cut a piece of material so that it is about 8-10 cm (3-4 in) wider than the pillow all round. Make a hem (with an opening) round the edge and thread either tape or elastic through it. Fit the cover over the pillow and pull the tape or elastic tight. (If you’re in a hurry just pin the cover in place.) This cover should be removed and washed occasionally. You will also need at least two cover cloths about 40 cm (16 in) square made of the same sort of material as the cover (they should be hemmed so no bits of thread can catch in the lace). One of these is placed over the lower part of the pricking and the bobbins lie on top of it. The other cloth is placed over the whole pillow when it is not in use so that the lace you’re working on stays clean. Making a Pricking In order to make bobbin lace you need a pattern known as a pricking. -

Illumination Underfoot the Design Origins of Mamluk Carpets by Peter Samsel

Illumination Underfoot The Design Origins of Mamluk Carpets by Peter Samsel Sophia: The Journal of Traditional Studies 10:2 (2004), pp.135-61. Mamluk carpets, woven in Cairo during the period of Mamluk rule, are widely considered to be the most exquisitely beautiful carpets ever created; they are also perhaps the most enigmatic and mysterious. Characterized by an intricate play of geometrical forms, woven from a limited but shimmering palette of colors, they are utterly unique in design and near perfect in execution.1 The question of the origin of their design and occasion of their manufacture has been a source of considerable, if inconclusive, speculation among carpet scholars;2 in what follows, we explore the outstanding issues surrounding these carpets, as well as possible sources of inspiration for their design aesthetic. Character and Materials The lustrous wool used in Mamluk carpets is of remarkably high quality, and is distinct from that of other known Egyptian textiles, whether earlier Coptic textiles or garments woven of wool from the Fayyum.3 The manner in which the wool is spun, however – “S” spun, rather than “Z” spun – is unique to Egypt and certain parts of North Africa.4,5 The carpets are knotted using the asymmetrical Persian knot, rather than the symmetrical Turkish knot or the Spanish single warp knot.6,7,8 The technical consistency and quality of weaving is exceptionally high, more so perhaps than any carpet group prior to mechanized carpet production. In particular, the knot counts in the warp and weft directions maintain a 1:1 proportion with a high degree of regularity, enabling the formation of polygonal shapes that are the most characteristic basis of Mamluk carpet design.9 The red dye used in Mamluk carpets is also unusual: lac, an insect dye most likely imported from India, is employed, rather than the madder dye used in most other carpet groups.10,11 Despite the high degree of technical sophistication, most Mamluks are woven from just three colors: crimson, medium blue and emerald green. -

SWOT Analysis and Related Countermeasures for Croatia To

CIRR XXIII (78) 2017, 169-185 ISSN 1848-5782 UDC 379.8:910.4(497.5:510) Vol.XVIII, No. 66 - 2012 Vol.XVIII, DOI 10.1515/cirr-2017-0012 XXIII (78) - 2017 SWOT Analysis and Related Countermeasures for Croatia to Explore the Chinese Tourist Source Market Wang Qian Abstract Croatia is a land endowed with rich and diversified natural and cultural tourist resources. Traveling around Croatia, I was stunned by its beauty. However, I noticed that there were few Chinese tourists in Croatia. How can we bring more Chinese tourists to Croatia? How can we make them happy and comfortable in Croatia? And, at the same time, how can we avoid polluting this tract of pure land? Based on first-hand research work, I make a SWOT analysis of the Chinese tourist source market of Croatia and put forward related countermeasures from the perspective of a native Chinese. The positioning of tourism in Croatia should be ingeniously packaged. I recommend developing diversified and specialized tourist products, various marketing and promotional activities, simple and flexible visa policies and regulations, and other related measures to further explore the Chinese tourist source market of Croatia. KEY WORDS: SWOT analysis, Croatia, Chinese tourist source market, sustainable tourism, direct flight 169 Introduction Vol.XVIII, No. 66 - 2012 Vol.XVIII, XXIII (78) - 2017 I worked in Zagreb, the capital of Croatia, for three years. During my stay, I walked almost all around Croatia. I travelled in Dalmatia for two weeks, visiting Zadar, Šibenik, Skradin, Trogir, Split, Hvar, Korčula and Dubrovnik. I toured Istria for a week, visiting Opatija, Pula, Rovinj and Poreč. -

The Rinceau Design, the Minor Arts and the St. Louis Psalter

The Rinceau Design, the Minor Arts and the St. Louis Psalter Suzanne C. Walsh A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Art History. Chapel Hill 2011 Approved by: Dr. Jaroslav Folda Dr. Eduardo Douglas Dr. Dorothy Verkerk Abstract Suzanne C. Walsh: The Rinceau Design, the Minor Arts and the St. Louis Psalter (Under the direction of Dr. Jaroslav Folda) The Saint Louis Psalter (Bibliothèque National MS Lat. 10525) is an unusual and intriguing manuscript. Created between 1250 and 1270, it is a prayer book designed for the private devotions of King Louis IX of France and features 78 illustrations of Old Testament scenes set in an ornate architectural setting. Surrounding these elements is a heavy, multicolored border that uses a repeating pattern of a leaf encircled by vines, called a rinceau. When compared to the complete corpus of mid-13th century art, the Saint Louis Psalter's rinceau design has its origin outside the manuscript tradition, from architectural decoration and metalwork and not other manuscripts. This research aims to enhance our understanding of Gothic art and the interrelationship between various media of art and the creation of the complete artistic experience in the High Gothic period. ii For my parents. iii Table of Contents List of Illustrations....................................................................................................v Chapter I. Introduction.................................................................................................1 -

Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of Terms Used in the Documentation – Blue Files and Collection Notebooks

Book Appendix Glossary 12-02 Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of terms used in the documentation – Blue files and collection notebooks. Rosemary Shepherd: 1983 to 2003 The following references were used in the documentation. For needle laces: Therese de Dillmont, The Complete Encyclopaedia of Needlework, Running Press reprint, Philadelphia, 1971 For bobbin laces: Bridget M Cook and Geraldine Stott, The Book of Bobbin Lace Stitches, A H & A W Reed, Sydney, 1980 The principal historical reference: Santina Levey, Lace a History, Victoria and Albert Museum and W H Maney, Leeds, 1983 In compiling the glossary reference was also made to Alexandra Stillwell’s Illustrated dictionary of lacemaking, Cassell, London 1996 General lace and lacemaking terms A border, flounce or edging is a length of lace with one shaped edge (headside) and one straight edge (footside). The headside shaping may be as insignificant as a straight or undulating line of picots, or as pronounced as deep ‘van Dyke’ scallops. ‘Border’ is used for laces to 100mm and ‘flounce’ for laces wider than 100 mm and these are the terms used in the documentation of the Powerhouse collection. The term ‘lace edging’ is often used elsewhere instead of border, for very narrow laces. An insertion is usually a length of lace with two straight edges (footsides) which are stitched directly onto the mounting fabric, the fabric then being cut away behind the lace. Ocasionally lace insertions are shaped (for example, square or triangular motifs for use on household linen) in which case they are entirely enclosed by a footside. See also ‘panel’ and ‘engrelure’ A lace panel is usually has finished edges, enclosing a specially designed motif. -

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Identification

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace DATS in partnership with the V&A DATS DRESS AND TEXTILE SPECIALISTS 1 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Text copyright © Jeremy Farrell, 2007 Image copyrights as specified in each section. This information pack has been produced to accompany a one-day workshop of the same name held at The Museum of Costume and Textiles, Nottingham on 21st February 2008. The workshop is one of three produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A, funded by the Renaissance Subject Specialist Network Implementation Grant Programme, administered by the MLA. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audiences. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the public. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Textile Types and Weaves 1750 -1950 Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740-1890 Front cover image: Detail of a triangular shawl of white cotton Pusher lace made by William Vickers of Nottingham, 1870. The Pusher machine cannot put in the outline which has to be put in by hand or by embroidering machine. The outline here was put in by hand by a woman in Youlgreave, Derbyshire. (NCM 1912-13 © Nottingham City Museums) 2 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Contents Page 1. List of illustrations 1 2. Introduction 3 3. The main types of hand and machine lace 5 4. -

Graded-In Textiles

Graded-In Textiles For a list of each of our partner commpany’s patterns with Boss • Indicate GRADED-IN TEXTILE on your order and Boss Design Design Grades visit www.bossdesign.com. To order memo will order the fabric and produce the specified furniture. samples visit the websites or call the numbers listed below. • Boss Design reserves the right to adjust grades to accommodate price changes received from our suppliers. • Refer to our website www.bossdesign.com for complete pattern memo samples: www.arc-com.com or 800-223-5466 lists with corresponding Boss Design grades. Fabrics priced above our grade levels and those with exceptionally large repeats are indicated with “CALL”. Please contact Customer Service for pricing. • Orders are subject to availability of the fabric from the supplier . • Furniture specified using multi-fabric applications or contrasting welts be up charged. memo samples: www.architex-ljh.com or 800-621-0827 may • Textiles offered in the Graded-in Textiles program are non- standard materials and are considered Customer’s Own Materials (COM). Because COMs are selected by and used at the request of a user, they are not warranted. It is the responsibility of the purchaser to determine the suitability of a fabric for its end use. memos: www.paulbraytondesigns.com or 800-882-4720 • In the absence of specific application instructions, Boss Design will apply the fabric as it is sampled by the source and as it is displayed on their website. memo samples: www.camirafabrics.com or 616 288 0655 • MEMO SAMPLES MUST BE ORDERED DIRECTLY FROM THE FABRIC SUPPLIER. -

A Working Vocabulary for the Study of Early Bobbin Lace 2015

A Working Vocabulary for the study of Early Bobbin Lace 2015 Introduction This is an attempt to define words used when discussing early bobbin lace; assembling the list has proved an incredibly difficult task! Among the problems are: the imprecision of the English language; the way words change their meaning over years/centuries; the differences between American English, English English and translations between English and other languages... The list has been compiled with the help of colleagues in Australia, Sweden, UK and USA; we come from very different experiences and in some cases it has been impossible to reach a precise definition that we all agree. In these cases either alternatives are given, or I have made decisions on which word to use. As the heading says, this is a working vocabulary, one I and others can use when studying early lace, and I am open to persuasion that different words and definitions might be better. 2015 Early bobbin lace - an open braid or fabric featuring plaits and twisted pairs, created by manipulation of multiple threads (each held on a small handle known as a bobbin); as made from the first half of the sixteenth century until an abrupt change in style in the1630s. Described in the sixteenth century as Bone Lace, also called Passamayne Lace (from the French for braid or trimming) or passement aux fuseaux. Reconstruction - a copy that, given the constraints of modern materials, is as close as possible to the original lace in size/proportion and technique. Interpretation - reproduction of lace from patterns or paintings, or where it is not possible to see the exact structure and/or proportions of the original lace Adaptation - taking an original lace, pattern or illustration and working it in a completely different material, scale or proportion. -

Approaches to Understanding Oriental Carpets Carol Bier, the Textile Museum

Graduate Theological Union From the SelectedWorks of Carol Bier February, 1996 Approaches to Understanding Oriental Carpets Carol Bier, The Textile Museum Available at: https://works.bepress.com/carol_bier/49/ 1 IU1 THE TEXTILE MUSEUM Approaches to Understanding Oriental Carpets CAROL BIER Curator, Eastern Hemisphere Collections The Textile Museum Studio photography by Franko Khoury MAJOR RUG-PRODUCING REGIONS OF THE WORLD Rugs from these regions share stylistic and technical features that enable us to identify major regional groupings as shown. Major Regional Groupings BSpanish (l5th century) ..Egypto-Syrian (l5th century) ItttmTurkish _Indian Persian Central Asian :mumm Chinese ~Caucasian 22 Major rug-producing regions of the world. Map drawn by Ed Zielinski ORIENTAL CARPETS reached a peak in production language, one simply weaves a carpet. in the late nineteenth century, when a boom in market Wool i.s the material of choice for carpets woven demand in Europe and America encouraged increased among pastoral peoples. Deriving from the fleece of a *24 production in Turkey, Iran and the Caucasus.* Areas sheep, it is a readily available and renewable resource. east of the Mediterranean Sea at that time were Besides fleece, sheep are raised and tended in order to referred to as. the Orient (in contrast to the Occident, produce dairy products, meat, lard and hide. The body which referred to Europe). To study the origins of these hair of the sheep yields the fleece. I t is clipped annually carpets and their ancestral heritage is to embark on a or semi-annually; the wool is prepared in several steps journey to Central Asia and the Middle East, to regions that include washing, grading, carding, spinning and of low rainfall and many sheep, to inhospitable lands dyeing. -

Ipswich Lace Workshop Materials Information

Ipswich Lace Workshop Materials Information Patterns, etc. provided to the students from the instructor: 1. Two Ipswich pattern packs of your choice. Please choose from the attached list. The samples are listed in approximate level of difficulty, with #2 being the easiest. 2. Prickings are printed on light grey cardstock and mailed to your snail mail address. 3. Color-coded working diagram 4. Corresponding pictures of the reconstructed lace and the original 1790 sample. Supply list: 1. Lace pillow, your preferred style for continuous lace, large enough to accommodate up to 50 pairs of bobbins 2. Bobbins (your preferred style) up to 50 pairs, depending on pattern choice 3. Pins – all the same size. The Ipswich lacemakers used handmade pins, which were approximately .60 to .65 mm in diameter. 4. Black silk thread, such as YLI 50, Clover 50, or Tiger (approximately 35-36 wraps/cm), or Piper spun silk 140/2 or Kreinik Au Ver a Soie 130/2 (42 wraps/cm) 5. Gimp thread: Gütermann 30/3 (S1003, 3-ply, approx. 16 wraps/cm) or Soie Perlee for a slightly thinner gimp. Or use 4-6 strands of your lace thread. 6. Two cover cloths. The one on the pillow, under the bobbins should be light color to contrast with the black threads. 7. Several short bobbin holders 8. Scissors, other regular bobbin lace supplies for continuous lace technique. 9. Wind on each bobbin about 4 times the length of lace you plan to make. Wind the number of bobbins indicated on your chosen pattern, singly or in pairs, depending on your preference.