Civille & Tang, Pllc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voting Record

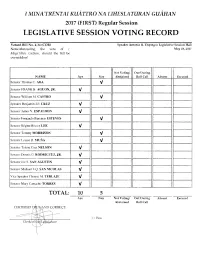

f; {) I MINA'TRENTAI KUATTRO NA LIHESLATURAN GUAHAN 2017 (FIRST) Regular Session LEGISLATIVE SESSION VOTING RECORD Vetoed Bill No. 4-34 (COR) Speaker Antonio R. Unpingco Legislative Session Hall Notwithstanding the veto of I May 23, 2017 l\ltaga'l:Hten (~u11han, should the Bill be overridden? I Not Votingi Out During I I I NAME Ave I Nav :\bst.,1.ined Roll Call Absent Excused l Senator Thomas C, ADA Senator FRA."iK B. AGUON, JR, " Senator William M. CASTRO " I ' Speaker Benjamin J.F. CRUZ i ! " iI ! ~ ! i James V. ESPALOON " i v I• ' Senator Fernando Barcinas ESTEVES Senator RCgine Bi~toe Lf:E " I-"- Senatur Tommy MORRISON " ' ' SenJtor Louise n. 1\'IlJN1\. I " I Telena Cruz NELSON l ~nator " l I I ISenator Dennis G. RODRIGUEZ, JR. "v l I ! Senanw Joe S. SAN AGUSTIN -·· Senator Michael F.Q. SAN NICOLAS " ! --I 1 !Vice Speaker There"' '.'L TERLAJE " ' I I ' I I Senator l\laiy Cainacho TORRES " i TOTAL: 10" 5 1\ye Nay Not Voting/ Out During Absent Abstained Roll Call l lvfina 'Trenrai Kuattro Na Liheslaturan Guahan THE 34TH GUAM LEGISLATURE MESSAGES AND COMMUNICATIONS Tel:(671) 472-3465 Fax: (671) 472-3547 TO: All Senators ({ii;} FROM: Senator Regine Biscoe Le~ Legislative Secretary SUBJECT: 34th GL Messages and Communications Below is a list and attachments of Messages and Communications received pursuant to Rule lll, of I Mina 'Trentai Kuaiiro Na Lihes/muran Gutlitan Standing Rules. These documents are available as well on our legislative website: \V\VW .guarnlegislature.con1. Should you have any questions or concerns, please contact the Clerk's office at 472-3465/74, V'ia Entail Letter dated March 20, 2017: Governor's N1essage on 34GL-l 7-0323 Office of the Governor of Guam Vetoed Bill No. -

Senator Frank B. Aguon, Jr

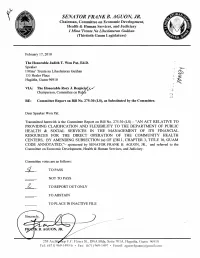

SENATOR FRANK B. AGUON, JR. Chairman, Committee on Economic Development, Health & Human Services, and Judiciary I Min a 'Trenta Na Lilteslaturan Gualtan (Thirtieth Guam Legislature) February 17, 2010 The Honorable Judith T. Won Pat, Ed.D. Speaker IMina' Trenta na Liheslaturan Guahan 155 Hesler Place Hagatfia, Guam 9691 0 VIA: The Honorable Rory J. Respici~ Chairperson, Committee on Rt9's RE: Committee Report on Bill No. 275-30 (LS), as Substituted by the Committee. Dear Speaker Won Pat: Transmitted herewith is the Committee Report on Bill No. 275-30 (LS)- "AN ACT RELATIVE TO PROVIDING CLARIFICATION AND FLEXIBILITY TO THE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH & SOCIAL SERVICES IN THE MANAGEMENT OF ITS FINANCIAL RESOURCES FOR THE DIRECT OPERATION OF THE COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTERS, BY AMENDING SUBSECTION (a) OF §3811, CHAPTER 3, TITLE 10, GUAM CODE ANNOTATED,"- sponsored by SENATOR FRANK B. AGUON, JR., and referred to the Committee on Economic Development, Health & Human Services, and Judiciary. Committee votes are as follows: TO PASS NOT TO PASS TO REPORT OUT ONLY TO ABSTAIN TO PLACE IN INACTNE FILE 23R Arch 10p F.C. Flores St., DNA Bldg, Suite 701 A. Hagatfia, Guan1 969 J 0 Tel: (671) 969-1495/6 • Fax: (671) 969-1497 • Email: aguon4guam(ag:mail.com SENATOR FRANK B. AGUON, JR. Chairman, Committee on Economic Development, Health & Human Services, and Judiciary I Min a 'Trenta Na Liheslaturan Guahan (Thirtieth Guam Legislature) COMMITTEE REPORT BILL NO. 275 (LS), as Substituted By the Committee on Economic Development, Health & Human Services, and Judiciary (by Senator Frank B. Aguon, Jr) "AN ACT RELATIVE TO PROVIDING CLARIFICATION AND FLEXffiiLITY TO THE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH & SOCIAL SERVICES IN THE MANAGEMENT OF ITS FINANCIAL RESOURCES FOR THE DIRECT OPERATION OF THE COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTERS, BY AMENDING SUBSECTION (a) OF §3811, CHAPTER 3, TITLE 10, GUAM CODE ANNOTATED." 238 Archbishop F.C. -

The Government of Guam

2 te GENERAYourL ELEC TIVoiceON 2012 YourGENERA L Vote ELECTION 2012 Vo r r ou Y , , ce Your guide to Election 2012 oi V INSIDE ur Voter initiative: he Pacific Daily tion on the for- community to help Yo Proposal A News provides this profit bingo pro- support public edu- guide to the 2012 posal that will be cation, safety and on the General health agencies. 12 Page 3 General Election to Election ballot On the other side help you, our readers 20 Nov. 6. of the argument, crit- and voters, make the 1, Congressional delegate Proponents of ics say passing the most informed deci- er Proposition A, pri- initiative could bring Pages 4, 5 Tsion about which marily the Guam- harm to Guam’s mb candidates have what it takes to bring Japan Friendship non-profit organiza- ve the island into the future. Village, only re- tions, a number of No Senatorial candidates We contacted candidates before the Gen- cently became vo- which rely on bingo , , — Democrat eral Election to get information about their cal — attending as a method of rais- ay work experience and education. We also village meetings and taking out radio spots ing funds to support their cause. One of the sd Pages 7~13 sent election-related questions to delegate and television ads calling for the communi- more vocal groups, “Keep Guam Good” ur and legislative candidates and asked them to ty’s support. raise concerns that for-profit bingo would be Th , , submit written responses. One legislative Proponents say the facility that the passage too similar to gambling and with the passage Senatorial candidates of the initiative would allow if passed by of the initiative would bring social ills that m m candidate, former Sen. -

United States/Cnmi Political Union

S. HRG. 110–164 UNITED STATES/CNMI POLITICAL UNION HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION TO RECEIVE TESTIMONY ON S. 1634, A BILL TO IMPLEMENT FURTHER THE ACT APPROVING THE COVENANT TO ESTABLISH A COMMONWEALTH OF THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS IN POLITICAL UNION WITH THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES JULY 19, 2007 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–192 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES JEFF BINGAMAN, New Mexico, Chairman DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho RON WYDEN, Oregon LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota RICHARD BURR, North Carolina MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JIM DEMINT, South Carolina MARIA CANTWELL, Washington BOB CORKER, Tennessee KEN SALAZAR, Colorado JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama BLANCHE L. LINCOLN, Arkansas GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon BERNARD SANDERS, Vermont JIM BUNNING, Kentucky JON TESTER, Montana MEL MARTINEZ, Florida ROBERT M. SIMON, Staff Director SAM E. FOWLER, Chief Counsel FRANK MACCHIAROLA, Republican Staff Director JUDITH K. PENSABENE, Republican Chief Counsel (II) C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS Page Akaka, Hon. Daniel K., U.S. Senator from Hawaii .............................................. 4 Bingaman, Hon. -

Frank Leon Guerrero/Democrat

FRANK LEON GUERRERO/DEMOCRAT QUESTIONNAIRE The deadline to submit written answers is September 30th, 2020 Legislative Candidate Interview Vying For Election To The 36th Guam Legislature A. Real Estate Industry Related 1. The Governor’s office has upgraded the classification of the real estate industry as an essential service during COVID-19 “Condition of Readiness” operating restrictions. However, the Government of Guam agencies that are part and parcel of the real estate industry remain either closed or inactive. (The real estate industry encompasses private sector real estate activities as well as Government of Guam agencies that are involved in the processing of real estate transactions including taxation, recordation, land management interaction, construction and land use permitting, building inspections, building occupancy, and document recordation.). Will you support the preparation and passage of legislation to classify the whole of the real estate industry encompassing both the private sector and related Government of Guam agencies as TRUE ESSENTIAL SERVICES? While I am aware of their being a distinction between “essential services” and “true essential services”. This crisis has forced the awareness of being able to operate the government by implementing a complete digital transformation of distinction government. In many communities across the country obtaining a mortgage and buying a home are processed entirely online. If elected I will work closely with the Association on legislation that will address these concerns. Real Estate is a critical part of our locally grown economy. 2. The Guam Land Use Commission (GLUC) application processing system has been rendered inactive by GovGuam COVID restrictions since March 2020 with no apparent urgency to restore the system to full operation. -

Political Reviews

Political Reviews 0LFURQHVLDLQ5HYLHZ,VVXHVDQG(YHQWV-XO\ WR-XQH david w kupferman, kelly g marsh, samuel f mcphetres, tyrone j taitano 3RO\QHVLDLQ5HYLHZ,VVXHVDQG(YHQWV-XO\WR-XQH lorenz gonschor, hapakuke pierre leleivai, margaret mutu, forrest wade young 7KH&RQWHPSRUDU\3DFL²F9ROXPH1XPEHU¥ E\8QLYHUVLW\RI+DZDL©L3UHVV 169 0LFURQHVLDLQ5HYLHZ,VVXHVDQG(YHQWV -XO\WR-XQH Reviews of the Federated States of major issue was the military buildup Micronesia, Kiribati, Nauru, and resulting from the transfer of the US Palau are not included in this issue. Marine units from Okinawa to Guam (MV, 28 Sept 2012). As in the primary, Guam Bordallo won the general election National and local elections featured handily, this time garnering 58 percent prominently in news stories in Guam of the vote. this year, as local offices and Guam’s Democrats controlled the Guam nonvoting delegate to the United Legislature by a 9 to 6 margin going States Congress were on the ballot. into the November elections. When The island’s incumbent, Congress- election results came in, voters had woman Madeleine Z Bordallo, faced again chosen a 9 to 6 Democratic challengers in both the Democratic majority, although one-third of the primary and the general election and legislature was replaced. The turn- prevailed against both. In the Septem- over in one seat was due to Frank ber primary, the five-term incumbent Blas Jr choosing to run for the US faced twenty-seven-year-old newcomer Congress rather than for reelection to Karlo Dizon (MV, 14 May 2013). the legislature. However, four other Despite Dizon’s spirited campaign, incumbents were defeated, namely, Bordallo won 73 percent of the vote. -

Statistical Yearbook

GGGUUUAAAMMM SSSTTTAAATTTIIISSSTTTIIICCCAAALLL YYYEEEAAARRRBBBOOOOOOKKK 2011 22001111 Bureau of Statistics and Plans Office of the Governor 2011 Guam Statistical Yearbook Bureau of Statistics and Plans Office of the Governor 2012 ii THE HONORABLE EDDIE BAZE CALVO GOVERNOR OF GUAM THE HONORABLE RAY TENORIO LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR Bureau of Statistics and Plans Sagan Planu Siha Yan Emfotmasion THOMAS A. MORRISON Government of Guam DIRECTOR A MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR Buenas yan Hafa Adai! The Bureau of Statistics and Plans is pleased to present to you the “2011 Guam Statistical Yearbook.” This comprehensive sourcebook presents a portrait of current and historical socio-economic statistics that reflect Guam’s economic development and performance over time. As Guam’s economy continues to progress from proceeds of increased tourism arrivals, developed job opportunities, the growing military presence, and the expected construction growth and infrastructure improvement, the Guam Statistical Yearbook serves as a valuable resource instrument in providing information needed to promote economic expansion and prosperity for the people. I am confident this report will provide our government, business and civic leaders with the information necessary to effectively develop immediate and long term strategies to address our island’s needs and generate investment opportunities to local and potential businesses alike. I commend the staff of the Bureau for their dedication and hard work and acknowledge the valuable contributions of the various government agencies and private sector businesses whose efforts have made this publication possible. It is my hope that the information in this report presents a clear picture of Guam’s economic condition and outlook in the upcoming years. -

Philippine Independence Month Long Celebration in Guam Commences with Proclamation Signing

PRR-ETQA-037-2017 PRESS RELEASE 01 June 2017 PHILIPPINE INDEPENDENCE MONTH LONG CELEBRATION IN GUAM COMMENCES WITH PROCLAMATION SIGNING Acting Head of Post Consul Edgar Tomas Q. Auxilian (seated 4th from left) with Acting Guam Governor Ray Tenorio (seated 5th from left), Senator Frank Aguon, Jr. of the 34th Guam Legislature (3rd from left), Mr. Norman Analista, President of the Filipino Community of Guam (FCG) (seated rightmost), FCG officers and board members, and other Filipino community leaders, at the presentation of Proclamation No. 2017-052 on 01 June 2017 at Triple J Motors, Upper Tumon, Guam. (Photo credits: PCG Agana) 01 June 2017, Agana, Guam - Acting Governor Ray Tenorio signed and presented on 01 June 2017 to the Filipino Community of Guam (FCG), umbrella organization of Filipino organizations on Guam, Proclamation No. 2017-052 declaring the month of June 2017 as Philippine Independence Month in honor of Filipino-Guamanians. The event was held at Triple J Motors, one of the biggest businesses on Guam and a partner of FCG in its various activities. The proclamation highlights the longstanding close and historical ties between the Philippines and Guam, and signals the start of the month-long activities in celebration of the 119th Anniversary of the Proclamation of Philippine Independence by the Consulate General, and the different Filipino organizations on Guam led by the FCG. In line with the theme, “Kalayaan 2017: Pagbabagong Sama-samang Balikatin (Independence 2017: Working Together for Change)”, Acting Head of Post Consul Edgar Tomas Q. Auxilian expressed his appreciation to the Government of Guam for the recognition accorded to Filipinos for their contribution to the good of their community. -

05 November 2010 Dear Reader

05 November 2010 Dear Reader: The enclosed articles are mission sustainment-related issues from the United States and abroad. They represent the good, the bad and the ugly aspects of the military/community interface on issues of mission sustainability. While we will attempt to cover the whole spectrum of issues, we will no doubt miss some items of interest. If you see any articles that you think may be of interest to others concerning encroachment, please forward them to us. We will be sending out an updated compilation weekly. Please let us know if you would like to be dropped from the distribution list. VR/ Navy AICUZ/RAICUZ Center of Excellence East Coast: Fred Pierson Bonnie Curtiss (757) 322-4935 (757) 322-4464 [email protected] [email protected] West Coast: Robert Henderson (619) 532-1622 [email protected] CONTENTS Page CALIFORNIA Joint Land Use Study with Camp Roberts forges ahead......................................................1 Closure Of Shooting Range Provokes An Unusual Clash...................................................2 HAWAII 'Armor Balls' deployed, make pilots safer ...........................................................................4 NEW MEXICO Base commander: Communication key in low-altitude training issue ................................6 SOUTH DAKOTA Air Force finishes hearings on expanded bomber training area ..........................................7 OVERSEAS AUSTRALIA Defence 'sitting on' RAAF noise maps ................................................................................8 -

Committee on Rules Issues Session Update

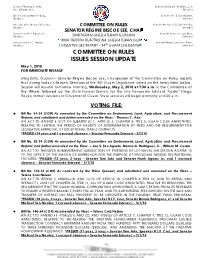

Senator Thomas C. Ada, Senator Dennis G. Rodriguez, Jr., Vice Chairperson Member Speaker Benjamin J.F. Cruz, Senator Joe S. San Agustin, Member Member Vice Speaker Therese M. Terlaje, COMMITTEE ON RULES Senator Michael F.Q. San Nicolas, Member Member SENATOR RÉGINE BISCOE LEE, CHAIR Senator Frank B. Aguon, Jr., Senator James V. Espaldon, Member SIKRITARIAN LIHESLATURAN GUÅHAN Member I MINA’TRENTAI KUÅTTRO NA LIHESLATURAN GUÅHAN Senator Telena C. Nelson, Senator Mary Camacho Torres, Member LEGISLATIVE SECRETARY • 34TH GUAM LEGISLATURE Member COMMITTEE ON RULES ISSUES SESSION UPDATE May 1, 2018 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Hagåtña, Guam)— Senator Régine Biscoe Lee, Chairperson of the Committee on Rules, reports that during today’s Session, Senators of the 34th Guam Legislature voted on the items listed below. Session will resume tomorrow morning, Wednesday, May 2, 2018 at 7:30 a.m. in the Committee of the Whole followed by the State Funeral Service for the late Honorable Edward "Eddie" Diego Reyes, former Lieutenant Governor of Guam. State services will begin promptly at 8:00 a.m. VOTING FILE: Bill No. 34-34 (COR) As amended by the Committee on Environment, Land, Agriculture, and Procurement Reform; and substituted and further amended on the Floor. – Thomas C. Ada AN ACT TO AMEND § 5127 OF SUBARTICLE C, ARTICLE 2, CHAPTER 5, TITLE 5, GUAM CODE ANNOTATED, RELATIVE TO LIMITING THE PERIOD OF VALIDITY OF DETERMINATION OF NEED AND THE REQUIREMENT FOR LEGISLATIVE APPROVAL OF EXCEPTIONAL TERM CONTRACTS. *PASSED (14 yeas and 1 excused absence – Senator Fernando Esteves) – 5/1/18 Bill No. 62-34 (COR) As amended by the Committee on Environment, Land, Agriculture and Procurement Reform; and further amended on the Floor. -

Political Reviews • Micronesia 189 Kelly G Marsh References

political reviews • micronesia 189 as several incumbent senators opted former reign as island governor (MV, not to run for reelection. Veteran 1 June 2006). Leading island polls as Senator Lou Leon Guerrero stepped of this writing were former US Con- down midterm to assume presidency gressman Robert Underwood and of the Bank of Guam, and three sena- Guam Senator Frank Aguon Jr, tors ran for lieutenant governor. touting the slogan “Leadership for The year 2006 marks the first time Change” (PDN, 31 March 2006). that the island’s attorney general and Island voters will once again decide public auditor positions will appear whether to keep the drinking age at on primary ballots. This will whittle eighteen or raise it to twenty-one. down the number of contenders to Senators have proposed that voters two candidates per position, ensuring also determine whether or not to that the seats are won by a majority retain former Education Superinten- rather than a plurality of votes. dent Flores, and whether or not to When the year under review ended, raise the minimum wage. there were four teams competing in kelly g marsh the race for governor. Incumbent Governor Felix Camacho and first- Special thanks to Tyrone J Taitano time Senator Mike Cruz ran under who helped to edit this review. the slogan, “Honest Men, Proven Leaders.” They were the first team to install large signage and saturate tele- References vision airwaves with messages noting GU, GU Magazine. Bi-monthly. Tamuning, the benefits that they had delivered to Guam: Papercut Publications. the island. However, media coverage <http://www.gumagazine.com/> of government shortfalls, the nonpay- MV, Marianas Variety—Guam Edition. -

Political Reviews

Political Reviews michael lujan bevacqua, elizabeth (isa) ua ceallaigh bowman, zaldy dandan, monica c labriola, nic maclellan, tiara r na'puti, gonzaga puas peter clegg, lorenz gonschor, margaret mutu, salote talagi, forrest wade young 187 political reviews • micronesia 195 FSM Constitution. 1978. Available on the Nanmadapw-Palikir, Pohnpei, 15 Septem- FSM Legal Information System website: ber. http://fsmlaw.org/fsm/constitution/index Sivas, Vince. 2019. Internet interview with .htm author, 16 September. FSM Public Law 18-34. 2013. Available Walter, Inos. 2019. Interview with author, from http://www.cfsm.gov.fm/index.php/ Weno, Chuuk, 3 September. legislations/public-laws/18th-fsm-congress -public-laws Zhang, Weidong. 2017. Interview with author, Palikir, Pohnpei, May. FSM Updates. 2014. President Mori Declares “State of Emergency” as Ping Da 7 Posts Greater Threat Sitting on Nan Kepkepin Param Reef in Pohnpei. Guam 23 January. http://myfsm.blogspot.com .au/2014/01/president-mori-declares-state The year 2018–2019 in Guam began -of.html on a high note with a series of land- Illon, Epel. 2019. Interview with author, mark elections and ended more Kolonia, Pohnpei, 13 September. forebodingly with a federal court case threatening the rights of the island’s Mori, Emanuel. 2019. Interview author, Kolonia, Pohnpei, 18 September. Indigenous people. November 2018 saw the victory Moufa, Richard. 2019. Interview with of Democrat Lourdes “Lou” Leon author, Kolonia, Pohnpei, 6 September. Guerrero as the island’s first female pit, Pacific Island Times. Daily Internet governor. For centuries, chief execu- and monthly print news. Tumon, Guam. tives on island have been referred to https://www.pacificislandtimes.com as “maga'låhi,” a colonial appropria- Puas, Gonzaga.