United States/Cnmi Political Union

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History and Cultivation of Parma Violets (Viola, Violaceae) in the United Kingdom and France in the Nineteenth Century

History AND Cultivation OF PARMA VIOLETS (VIOLA, VIOLACEAE) IN THE UNITED KINGDOM AND FRANCE IN THE NINETEENTH Century LUÍS MENDONÇA DE CARVALHO,1,2 FRANCISCA MARIA FERNANDES,3 MARIA DE FÁTIMA NUNES,3 JOÃO BRIGOLA,3 NATHALIE CASBAS,4 AND CLIVE GROVES5 Abstract. Scented cultivars of Parma violets were among the most important urban plants during the nineteenth century, with many references in literature, fashion, art and flower trade. Our research analyzed data related to Parma violets in France and in the United Kingdom and presents the cultivars introduced during the nineteenth century. Keywords: Parma violets, Viola cultivars, United Kingdom, France, social history The first records describing the use of violets origin. Earlier Italian literature from the XVI (Viola L., Violaceae) in Europe are from Ancient century refers to violets with a strong fragrance Greece: fragrant violets were sold in the and pleiomerous flowers that were obtained Athenian agora; praised by Greek poets, as in the from the East, near the city of Constantinople writings of Sappho (Jesus, 2009); used in (now Istanbul), capital of the former Byzantine medicine (Theophrastus, 1916); had an active role Empire. These texts describe violets that looked in myths, such as in the abduction of Persephone like roses, probably referring to ancestral plants (Ovid, 1955; Grimal, 1996); were used in gar- of the contemporary Parma violets (Malécot et lands (Goody, 1993) and present in the Odyssey’s al., 2007). In Naples (Italy), a local tradition garden of Calypso (Homer, 2003). They proposes that these violets came from Portugal, continued to be used throughout the Middle Ages brought by the Bourbon royal family during the and were present in Renaissance herbals (Cleene XVIII century; hence the local name Violetta and Lejeune, 2002). -

Trusteeship Cou Neil

UNITED NATIONS T Trusteeship Cou neil Distr. GENERAL T/PV.l649 12 May 1988 ENGLISH Fifty-fifth Session VERBATIM REQ)RD OF THE SIXTEEN HUNDRED AND FORTY-NINTH MEETING Held at Headquarters, New York, on Wednesday, 11 May 1988, at 3 p.rn. President: Mr. GAUSSOT (France) - Dissemination of information on the United Nations and the International Trusteeship system in Trust Territories; report of the Secretary-General (T/1924) [Trusteeship Council resolution 36 (III) and General Assembly resolution 754 (VIII)] Examination of petitions listed in the annex to the agenda (T/1922/Add.l) - Organization of work This record is subject to correction. Corrections should be submitted in one of the working languages, preferably in the same language as the text to which they refer. They should be set forth in a memorandum and also, if possible, incorporated in a copy of the record. They should be sent, within one week of the date of this document, to the Chief, Official Records Editing Section, Department of Conference Services, room DC2-750, 2 United Nations Plaza, and incorpora ted in a copy of the record. Any corrections to the records of the meetings of this session will be consolidated in a single corrigendum, to be issued shortly after the end of the session. 88-60564 4211V ( E) RM/3 T/PV.l649 2 The meeting was called to order at 3.20 p.m. DISSEMINATION OF INFORMATION ON THE UNITED NATIONS AND THE INTERNATIONAL TRUSTEESHIP SYSTEM IN TRUST TERRITORIES; REPORT OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL (T/1924) {TRUSTEESHIP COUNCIL RESOLUTION 36 (III) AND GENERAL ASSEMBLY RESOLUTION 754 (VIII)] The PRESIDENT (interpretation from French): I call upon Mr. -

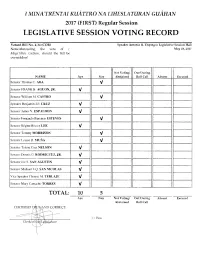

Voting Record

f; {) I MINA'TRENTAI KUATTRO NA LIHESLATURAN GUAHAN 2017 (FIRST) Regular Session LEGISLATIVE SESSION VOTING RECORD Vetoed Bill No. 4-34 (COR) Speaker Antonio R. Unpingco Legislative Session Hall Notwithstanding the veto of I May 23, 2017 l\ltaga'l:Hten (~u11han, should the Bill be overridden? I Not Votingi Out During I I I NAME Ave I Nav :\bst.,1.ined Roll Call Absent Excused l Senator Thomas C, ADA Senator FRA."iK B. AGUON, JR, " Senator William M. CASTRO " I ' Speaker Benjamin J.F. CRUZ i ! " iI ! ~ ! i James V. ESPALOON " i v I• ' Senator Fernando Barcinas ESTEVES Senator RCgine Bi~toe Lf:E " I-"- Senatur Tommy MORRISON " ' ' SenJtor Louise n. 1\'IlJN1\. I " I Telena Cruz NELSON l ~nator " l I I ISenator Dennis G. RODRIGUEZ, JR. "v l I ! Senanw Joe S. SAN AGUSTIN -·· Senator Michael F.Q. SAN NICOLAS " ! --I 1 !Vice Speaker There"' '.'L TERLAJE " ' I I ' I I Senator l\laiy Cainacho TORRES " i TOTAL: 10" 5 1\ye Nay Not Voting/ Out During Absent Abstained Roll Call l lvfina 'Trenrai Kuattro Na Liheslaturan Guahan THE 34TH GUAM LEGISLATURE MESSAGES AND COMMUNICATIONS Tel:(671) 472-3465 Fax: (671) 472-3547 TO: All Senators ({ii;} FROM: Senator Regine Biscoe Le~ Legislative Secretary SUBJECT: 34th GL Messages and Communications Below is a list and attachments of Messages and Communications received pursuant to Rule lll, of I Mina 'Trentai Kuaiiro Na Lihes/muran Gutlitan Standing Rules. These documents are available as well on our legislative website: \V\VW .guarnlegislature.con1. Should you have any questions or concerns, please contact the Clerk's office at 472-3465/74, V'ia Entail Letter dated March 20, 2017: Governor's N1essage on 34GL-l 7-0323 Office of the Governor of Guam Vetoed Bill No. -

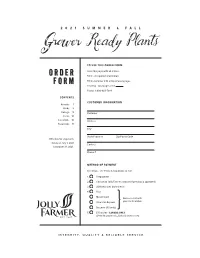

Orderform.Pdf

2021 SUMMER & FALL TO USE THIS ORDER FORM Send this page with all orders. Fill in all required information. Fill in customer info at top of every page. If faxing - total pages sent Fax to: 1-800-863-7814. CONTENTS CUSTOMER INFORMATION Annuals 1 Herbs 9 Foliage 9 Customer Ferns 10 Succulents 10 Address Perennials 11 City State/Province Zip/Postal Code Effective for shipments between July 1, 2021 Contact & October 31, 2021. Phone # METHOD OF PAYMENT For details, see Terms & Conditions of Sale. 1. Prepayment 2. Charge on Jolly Farmer account (if previously approved) 3. ACH (replaces draft check) 4. Visa MasterCard Give us a call with American Express your card number. Discover (US only) 5. E-Transfer - CANADA ONLY (Send to: [email protected]) CALENDULa – FLOWERING KALE Customer Name Zip/Postal ☑ Mark desired size Fill in desired shipdates Trays Strips ▼ Tag Code Specie Variety 512 288 144 26 51 Qty Annuals 1165 Calendula , Costa Mix 512 288 144 n/a n/a 1800 Dianthus , Coronet Mix 512 288 144 n/a n/a 1805 Dianthus , Coronet Strawberry 512 288 144 n/a n/a 1815 Dianthus , Diana Mix Formula 512 288 144 n/a n/a 1820 Dianthus , Diana Mix Lavendina 512 288 144 n/a n/a 1825 Dianthus , Diana Mix Picotee 512 288 144 n/a n/a 1830 Dianthus , Ideal Select Mix 512 288 144 n/a n/a 1840 Dianthus , Ideal Select Red 512 288 144 n/a n/a 1845 Dianthus , Ideal Select Rose 512 288 144 n/a n/a 1850 Dianthus , Ideal Select Violet 512 288 144 n/a n/a 1852 Dianthus , Ideal Select White 512 288 144 n/a n/a 1855 Dianthus , Ideal Select Whitefire 512 288 -

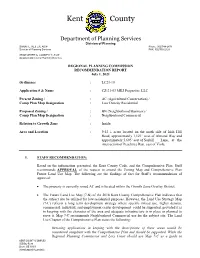

Recommendation Report Packet

Kent County Department of Planning Services Division of Planning SARAH E. KEIFER, AICP Phone: 302/744-2471 Director of Planning Services FAX: 302/736-2128 KRISTOPHER S. CONNELLY, AICP Assistant Director of Planning Services REGIONAL PLANNING COMMISSION RECOMMENDATION REPORT July 1, 2021 Ordinance : LC21-10 Application # & Name : CZ-21-03 MKJ Properties, LLC Present Zoning / : AC (Agricultural Conservation) / Comp Plan Map Designation : Low Density Residential Proposed Zoning / : BN (Neighborhood Business) / Comp Plan Map Designation : Neighborhood Commercial Relation to Growth Zone : Inside Area and Location : 9.52 ± acres located on the north side of Irish Hill Road, approximately 1,121’ west of Almond Way and approximately 5,695’ east of Sanbill Lane, at the intersection of Peachtree Run, east of Viola. I. STAFF RECOMMENDATION: Based on the information presented, the Kent County Code, and the Comprehensive Plan, Staff recommends APPROVAL of the request to amend the Zoning Map and Comprehensive Plan Future Land Use Map. The following are the findings of fact for Staff’s recommendation of approval: • The property is currently zoned AC and is located within the Growth Zone Overlay District. • The Future Land Use Map (7-B) of the 2018 Kent County Comprehensive Plan indicates that the subject site be utilized for low-residential purposes. However, the Land Use Strategy Map (7-C) reflects a long term development strategy where specific mixed use, higher density, commercial, industrial, and employment center development could be supported, provided it is in keeping with the character of the area and adequate infrastructure is in place or planned to serve it. Map 7-C recommends Neighborhood Commercial use for the subject site. -

I N O S R E B U T S O N D E M a P a N S U I T

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII LIBRA! Micronesia’s Leading Newspaper Since 1972 Vol. 21 Wo. 26 ....... Saipan MP 96950 •&1992 Marianas Variety ' T uesday " A pril 21, 1992 Serving CNMI for 20 Years Inos rebuts on Dem apan suit, seeks dism issal by Rafael H. Arroyo cusations made by Demapan in to state a claim upon which relief and committee membership in the his lawsuit against the Senate can be granted; to state a claim Senate as effected by Inos. leadership. which is justiciable by the court; The suit, the first of its kind in President Josephs. Inos recently Senate Legal Counsel Pam and to allege a judicially cogni in the history of the lawmaking came up with a response on the Brown asked the court to dismiss zable injury which resulted from body, sought relief on two causes suit filed by Senator Juan S. the suit, saying the plaintiff failed the putatively illegal conduct of of action meant to correct the al Damapan asking the Superior to come up with a strong case the defendant. leged inequity as claimed by the Court to dismiss the complaint for against the defendant. Demapan sued Inos and his plaintiff. lack of merit. According to the defendant’s brother, Eloy, in the latter’s ca The first cause of action alleges The attorney for Senate Presi- response the complaint should be pacity as Finance director, over that Saipan senators are inad dentlnos last weekfiled an answer dismissed for failure to include the alleged inequity over the equately represented on certain in the trial court rebutting the ac all necessary and proper parties; distribution of operational funds Senate committees, thus, violat ing the “equal representation” IHVU cniLU KtiV , clause of Section 203 (c) of the Covenant. -

Saipan Tribune Page 2 of 2

Saipan Tribune Page 2 of 2 ,,," '."..,..US,." .Y """I,"', "...I,, -.-.A I., .I," -I...", .Y. ..,",. .'U""'J, I IYI""IIIIY."~I justified. The area is said to have vegetation and a small pond. The Navy's land use request was coursed through the Office of the Veterans Affairs. Story by Liberty Dones Contact this reporter http://www.saipantribune.com/newsstory.aspx?cat=l&newsID=27904 4/29/03 Marianas Variety On-Line Edition Page 1 of 1 Community biiilcls ties with sailors (DCCA) - Saipan’s reputation as a port of call for U.S. Navy ships is receiving a big boost thanks to a new program that’s building personal ties between island families and sailors. Under its new Sponsor-A-Service Member program, the Department of Community and Cultural Affairs put 18 visiting sailors from the USS Antietam in touch with a local family who voluntarily hosted them while the ship was in Saipan earlier this month. “I want to thank... everyone on your island paradise for making our visit ...on Saipan the best Port Call I’ve ever had - ever!” said Lt. Cmdr. Timothy White, ship chaplain. “Your kindness and hospitality were like nothing we had ever experienced before.” Mite and other sailors were welcomed into the home of Noel and Rita Chargualaf, the first of Saipan residents to sign up for the program. “Every single man who participated has just raved about the wonderful time they had with the families,” said White. “You truly live in an island paradise and the people on your island are the nicest folks I have ever met.” “For the most, they were just thrilled to be around children and families. -

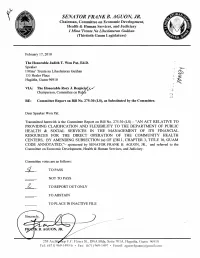

Senator Frank B. Aguon, Jr

SENATOR FRANK B. AGUON, JR. Chairman, Committee on Economic Development, Health & Human Services, and Judiciary I Min a 'Trenta Na Lilteslaturan Gualtan (Thirtieth Guam Legislature) February 17, 2010 The Honorable Judith T. Won Pat, Ed.D. Speaker IMina' Trenta na Liheslaturan Guahan 155 Hesler Place Hagatfia, Guam 9691 0 VIA: The Honorable Rory J. Respici~ Chairperson, Committee on Rt9's RE: Committee Report on Bill No. 275-30 (LS), as Substituted by the Committee. Dear Speaker Won Pat: Transmitted herewith is the Committee Report on Bill No. 275-30 (LS)- "AN ACT RELATIVE TO PROVIDING CLARIFICATION AND FLEXIBILITY TO THE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH & SOCIAL SERVICES IN THE MANAGEMENT OF ITS FINANCIAL RESOURCES FOR THE DIRECT OPERATION OF THE COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTERS, BY AMENDING SUBSECTION (a) OF §3811, CHAPTER 3, TITLE 10, GUAM CODE ANNOTATED,"- sponsored by SENATOR FRANK B. AGUON, JR., and referred to the Committee on Economic Development, Health & Human Services, and Judiciary. Committee votes are as follows: TO PASS NOT TO PASS TO REPORT OUT ONLY TO ABSTAIN TO PLACE IN INACTNE FILE 23R Arch 10p F.C. Flores St., DNA Bldg, Suite 701 A. Hagatfia, Guan1 969 J 0 Tel: (671) 969-1495/6 • Fax: (671) 969-1497 • Email: aguon4guam(ag:mail.com SENATOR FRANK B. AGUON, JR. Chairman, Committee on Economic Development, Health & Human Services, and Judiciary I Min a 'Trenta Na Liheslaturan Guahan (Thirtieth Guam Legislature) COMMITTEE REPORT BILL NO. 275 (LS), as Substituted By the Committee on Economic Development, Health & Human Services, and Judiciary (by Senator Frank B. Aguon, Jr) "AN ACT RELATIVE TO PROVIDING CLARIFICATION AND FLEXffiiLITY TO THE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH & SOCIAL SERVICES IN THE MANAGEMENT OF ITS FINANCIAL RESOURCES FOR THE DIRECT OPERATION OF THE COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTERS, BY AMENDING SUBSECTION (a) OF §3811, CHAPTER 3, TITLE 10, GUAM CODE ANNOTATED." 238 Archbishop F.C. -

Civille & Tang, Pllc

CIVILLE & TANG, PLLC Sender’s Direct E-Mail: www.civilletang.com [email protected] December 5, 2017 VIA HAND DELIVERY The Honorable Benjamin J.F. Cruz Speaker The 34th Guam Legislature 33rd Guam Legislature 155 Hesler Place Hagåtña, Guam 96932 Senator Frank B. Aguon, Jr. Chairperson Committee on Guam-U.S. Military Buildup, Infrastructure, and Transportation The 34th Guam Legislature 33rd Guam Legislature 155 Hesler Place Hagåtña, Guam 96932 Re: Bill No.204-34 (COR) – Frank B. Aguon, Jr. An act to amend §§ 58D105(a) and 59D112, and add a new §58D105(e), all of Chapter 58D, Title 5, Guam Code Annotated, relative to designating the Guam Department of Education as the Procuring entity for purposes of any solicitation respecting the Construction and/or Renovation of Simon Sanchez High School under a longterm lease-back. Dear Speaker Cruz and Senator Aguon: Thank you for the opportunity to provide comments on Bill No. 204-34 (the “Bill”). This letter serves as written testimony on behalf of Core Tech International Corp. (“Core Tech”) with regard to Bill No. 204-34. Bill No. 204-34, proposed by Senator Frank Aguon is an effort to move forward the procurement of Simon Sanchez High School (“SSHS”). The Bill seeks to amend the Ma Kahat Act, 5 G.C.A. § 58D, and change the procurement agency for SSHS to the Department of Education (“DOE”) instead of the Department of Public Works (“DPW”). DOE will not only be in charge of the procurement, but it will also be granted the authority to bypass a pending protest and proceed with an award if it finds that such an “award of the contract without delay is necessary to protect substantial interests of the Territory.” Bill No. -

The Government of Guam

2 te GENERAYourL ELEC TIVoiceON 2012 YourGENERA L Vote ELECTION 2012 Vo r r ou Y , , ce Your guide to Election 2012 oi V INSIDE ur Voter initiative: he Pacific Daily tion on the for- community to help Yo Proposal A News provides this profit bingo pro- support public edu- guide to the 2012 posal that will be cation, safety and on the General health agencies. 12 Page 3 General Election to Election ballot On the other side help you, our readers 20 Nov. 6. of the argument, crit- and voters, make the 1, Congressional delegate Proponents of ics say passing the most informed deci- er Proposition A, pri- initiative could bring Pages 4, 5 Tsion about which marily the Guam- harm to Guam’s mb candidates have what it takes to bring Japan Friendship non-profit organiza- ve the island into the future. Village, only re- tions, a number of No Senatorial candidates We contacted candidates before the Gen- cently became vo- which rely on bingo , , — Democrat eral Election to get information about their cal — attending as a method of rais- ay work experience and education. We also village meetings and taking out radio spots ing funds to support their cause. One of the sd Pages 7~13 sent election-related questions to delegate and television ads calling for the communi- more vocal groups, “Keep Guam Good” ur and legislative candidates and asked them to ty’s support. raise concerns that for-profit bingo would be Th , , submit written responses. One legislative Proponents say the facility that the passage too similar to gambling and with the passage Senatorial candidates of the initiative would allow if passed by of the initiative would bring social ills that m m candidate, former Sen. -

Avert Primary by Rafasl H

· V ·1 24 N .. 220 . .. ·. ·, . '. .· .... ;.· .. ,. ·· . .· :- .· .,.- · .. · . ··, .· ',. · ·.·. .. ·.· ... ·--·· .... ·.,.,, .. ·, ... :- '·.,,, .. ,;<',\·• · o. O. · · · ·... : · .. ·. '· •. ·. · ·. · .·. ·; · · · . < · ' · ..- .. ··. , . ; , _. : ·. '·.r"Sai'pan · Mfr96950;:~-,-,::1,&:ft~,t ©1996, Marianas Vari_ety : ·,, .· .' ·. '' ' .... ~r·~~,- .•· ~an ..a_ry: .. _1.9;~·· ..1,.9.~6 :_ ., ' -'· .. S,e'r•Jing CNMi-for~23:-Y.;;,f\~,V/:.;.l~;t- • • • - • • ' ' ' • j • - • ' , • • • • • • ' • ·: ,. ' • - ~ ' • - ~ , • ,. • ·"" • •:·1,.:::~ i\ -"!l.•::}"i, GOP to try to avert primary By Rafasl H. Arroyo nounced their intention to seek cratic challenger Froilan C. Variety News Staff the party's nomination to run in Tenorio. AS MUCH as possible, a primary the 1997 gubernatorial polls. Although Guerrero won over to select a candidate for the gu Babauta has already submitted Babauta and Demapan in the May Pedro P. Tenorio Juan N. Babauta bernatorial elections should be a letter ofintent to Fitial officially 1993 preliminary vote, the incum avoided, leaders from the Repub signifying his intention to seek bent lost to Froilan Tenorio in the lican Party said. the governorship. November gubernatorial tussle. In separate interviews, Party It was unclear if Tenorio had There were those who attrib chainnan Benigno R. Fitial and already turned in his intent letter, uted the 1993 Democratic victory candidates committee chairman but he has publicly said he is to the party's failure to heal the Joe I. Guerrero said it would in interested. wounds created by the primary. deed be to the party's best interest A third possible contender, Apparently, supporters of the if its candidates are selected by former Gov. Larry I. Guerrero is three protagonists remained split consensus rather than thru a pri currently weighing his options on despite post-primary pledges of mary. -

Micronesian Sub-Regional Diplomacy

15 Micronesian Sub-Regional Diplomacy Suzanne Lowe Gallen Shifts in Pacific diplomacy, governance and development priorities are changing the context of Pacific regionalism. In these shifts, Melanesian countries are represented by the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG) and Polynesian countries have formed their own sub-regional response via the Polynesian Leaders Group (PLG). But what of the Micronesian sub-region? Little is known of the North Pacific’s sub-regional experience, let alone its history, cultural context and governance structures. This chapter will highlight some of those experiences by pointing out the similarities and differences between the two main Micronesian sub-regional entities: the Micronesian Presidents Summit (MPS) and the Micronesian Chief Executives Summit (MCES), as well as some of the failures and successes of Micronesian sub-regionalism. There are several prevailing misconceptions, and perhaps misrepresentations, of the north Oceanic sub-region. It is perhaps a misnomer to use the term ‘North Pacific’ when referring to Micronesia because Kiribati and Nauru are geographically south — the equator being the obvious divider. The terminology may sometimes also be complicated by geographic references in the United States — the ‘North Pacific’ or ‘Pacific Northwest’ refer to the US states of Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia. It is sometimes important to make this distinction because of the close Micronesian affiliations with the US. The confusion may not be so much of an issue in the South Pacific, where 175 THE NEW PACIFIC DIPLOMACY the US North Pacific probably is hardly ever, if at all, a topic of discussion or reference. It is undoubtedly more geographically and politically correct to refer to the sub-region as ‘Northern and Central Oceania’ or simply the ‘Central Pacific.’ Another identifying term that is used for the three northern Micronesian sovereign states is the ‘Freely Associated States’ (FAS), which is an entirely neo-colonial term in the sense that its primary reference is to the sub- region’s relationship with the US.