Western Lakes Population Movement, Food Security and Livelihoods Profile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of South Sudan "Establishment Order

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN "ESTABLISHMENT ORDER NUMBER 36/2015 FOR THE CREATION OF 28 STATES" IN THE DECENTRALIZED GOVERNANCE SYSTEM IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Order 1 Preliminary Citation, commencement and interpretation 1. This order shall be cited as "the Establishment Order number 36/2015 AD" for the creation of new South Sudan states. 2. The Establishment Order shall come into force in thirty (30) working days from the date of signature by the President of the Republic. 3. Interpretation as per this Order: 3.1. "Establishment Order", means this Republican Order number 36/2015 AD under which the states of South Sudan are created. 3.2. "President" means the President of the Republic of South Sudan 3.3. "States" means the 28 states in the decentralized South Sudan as per the attached Map herewith which are established by this Order. 3.4. "Governor" means a governor of a state, for the time being, who shall be appointed by the President of the Republic until the permanent constitution is promulgated and elections are conducted. 3.5. "State constitution", means constitution of each state promulgated by an appointed state legislative assembly which shall conform to the Transitional Constitution of South Sudan 2011, amended 2015 until the permanent Constitution is promulgated under which the state constitutions shall conform to. 3.6. "State Legislative Assembly", means a legislative body, which for the time being, shall be appointed by the President and the same shall constitute itself into transitional state legislative assembly in the first sitting presided over by the most eldest person amongst the members and elect its speaker and deputy speaker among its members. -

Communities Tackling Small Arms and Light Weapons in South Sudan Briefing

Briefing July 2018 Communities tackling small arms and light weapons in South Sudan Lessons learnt and best practices Introduction The proliferation and misuse of small arms and light Clumsy attempts at forced disarmament have created fear weapons (SALW) is one of the most pervasive problems and resentment in communities. In many cases, arms end facing South Sudan, and one which it has been struggling up recirculating afterwards. This occurs for two reasons: to reverse since before independence in July 2011. firstly, those carrying out enforced disarmaments are – either deliberately or through negligence – allowing Although remoteness and insecurity has meant that seized weapons to re-enter the illicit market. Secondly, extensive research into the exact number of SALW in there have been no simultaneous attempts to address the circulation in South Sudan is not possible, assessments of demand for SALW within the civilian population. While the prevalence of illicit arms are alarming. conflict and insecurity persists, demand for SALW is likely to remain. Based on a survey conducted in government controlled areas only, the Small Arms Survey estimated that between In April 2017, Saferworld, with support from United 232,000–601,000 illicit arms were in circulation in South Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS), launched a project Sudan in 20161. It is estimated that numbers of SALW are to identify and improve community-based solutions likely to be higher in rebel-held areas. to the threats posed by the proliferation and misuse of SALW. The one-year pilot project aimed to raise Estimates also vary from state to state within South awareness among communities about the dangers of Sudan. -

National Education Statistics

2016 NATIONAL EDUCATION STATISTICS FOR THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN FEBRUARY 2017 www.goss.org © Ministry of General Education & Instruction 2017 Photo Courtesy of UNICEF This publication may be used as a part or as a whole, provided that the MoGEI is acknowledged as the source of information. The map used in this document is not the official maps of the Republic of South Sudan and are for illustrative purposes only. This publication has been produced with financial assistance from the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) and technical assistance from Altai Consulting. Soft copies of the complete National and State Education Statistic Booklets, along with the EMIS baseline list of schools and related documents, can be accessed and downloaded at: www.southsudanemis.org. For inquiries or requests, please use the following contact information: George Mogga / Director of Planning and Budgeting / MoGEI [email protected] Giir Mabior Cyerdit / EMIS Manager / MoGEI [email protected] Data & Statistics Unit / MoGEI [email protected] Nor Shirin Md. Mokhtar / Chief of Education / UNICEF [email protected] Akshay Sinha / Education Officer / UNICEF [email protected] Daniel Skillings / Project Director / Altai Consulting [email protected] Philibert de Mercey / Senior Methodologist / Altai Consulting [email protected] FOREWORD On behalf of the Ministry of General Education and Instruction (MoGEI), I am delighted to present The National Education Statistics Booklet, 2016, of the Republic of South Sudan (RSS). It is the 9th in a series of publications initiated in 2006, with only one interruption in 2014, a significant achievement for a new nation like South Sudan. The purpose of the booklet is to provide a detailed compilation of statistical information covering key indicators of South Sudan’s education sector, from ECDE to Higher Education. -

Vistas) Q3 Fy 2017 Quarterly Report April 1– June 30, 2017

VIABLE SUPPORT TO TRANSITION AND STABILITY (VISTAS) Q3 FY 2017 QUARTERLY REPORT APRIL 1– JUNE 30, 2017 JUNE 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by AECOM. VIABLE SUPPORT TO TRANSITION AND STABILITY (VISTAS) Q2 FY 2017 QUARTERLY REPORT APRIL 1 – JUNE 30, 2017 Contract No. AID-668-C-13-00004 Submitted to: USAID South Sudan Prepared by: AECOM International Development Prepared for: Office of Transition and Conflict Mitigation (OTCM) USAID South Sudan Mission American Embassy Juba, South Sudan DISCLAIMER: The authors’ views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Q3 FY 2017 Quarterly Report | Viable Support to Transition and Stability (VISTAS) i TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 1 II. Political And Security Landscape .................................................................................... 2 National Political and Security Landscape ..................................................................................................... 2 Political & Security Landscape in VISTAS Regional Offices ...................................................................... 3 III. Program Strategy.............................................................................................................. 6 IV. Program Highlights .......................................................................................................... -

Tracking the Flow of Government Transfers Financing Local Government Service Delivery in South Sudan

Tracking the flow of Government transfers Financing local government service delivery in South Sudan 1.0 Introduction The Government of South Sudan through its Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MoFEP) makes transfers of funds to states and local governments on a monthly basis to finance service delivery. Broadly speaking, the government makes five types of transfers to the local government level: a) Conditional salary transfers: these funds are transferred to be used by the county departments of education, health and water to pay for the salaries of primary school teachers, health workers and water sector workers respectively. b) Operation transfers for county service departments: these funds are transferred to the counties for the departments of education, health and water to cater for the operation costs of these county departments. c) County block transfer: each county receives a discretionary amount which it can spend as it wishes on activities of the county. d) Operation transfer to service delivery units (SDUs): these funds are transferred to primary schools and primary health care facilities under the jurisdiction of each county to cater for operation costs of these units. e) County development grant (CDG): the national annual budget includes an item to be transferred to each county to enable the county conduct development activities such as construction of schools and office blocks; in practice however this money has not been released to the counties since 2011 mainly due to a lack of funds. 2.0 Transfer and spending modalities/guidelines Funds are transferred by the national Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning from the government accounts at Bank of South Sudan to the respective state’s bank accounts through the state ministries of Finance (SMoF). -

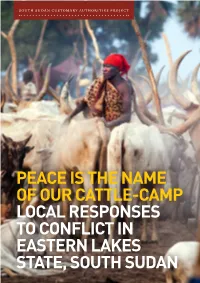

Peace Is the Name of Our Cattle-Camp By

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT PEACE IS THE NAME OF OUR CATTLE-CAMP LOCAL RESPONSES TO CONFLICT IN EASTERN LAKES STATE, SOUTH SUDAN SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT Peace is the Name of Our Cattle-Camp Local responses to conflict in Eastern Lakes State, South Sudan JOHN RYLE AND MACHOT AMUOM Authors John Ryle (co-author), Legrand Ramsey Professor of Anthropology at Bard College, New York, was born and educated in the United Kingdom. He is lead researcher on the RVI South Sudan Customary Authorities Project. Machot Amuom Malou (co-author) grew up in Yirol during Sudan’s second civil war. He is a graduate of St. Lawrence University, Uganda, and a member of The Greater Yirol Youth Union that organised the 2010 Yirol Peace Conference. Abraham Mou Magok (research consultant) is a graduate of the Nile Institute of Management Studies in Uganda. Born in Aluakluak, he has worked in local government and the NGO sector in Greater Yirol. Aya piŋ ëë kͻcc ἅ luël toc ku wεl Ɣͻk Ɣͻk kuek jieŋ ku Atuot akec kaŋ thör wal yic Yeŋu ye köc röt nͻk wεt toc ku wal Mith thii nhiar tͻͻŋ ku ran wut pεεc Yin aci pεεc tik riεl Acin ke cam riεlic Kͻcdit nyiar tͻͻŋ Ku cͻk ran nͻk aci yͻk thin Acin ke cam riεlic Wut jiëŋ ci riͻc Wut Atuot ci riͻc Yok Ɣen Apaak ci riͻc Yen ya wutdie Acin kee cam riεlic ëëë I hear people are fighting over grazing land. Cattle don’t fight—neither Jieŋ cattle nor Atuot cattle. Why do we fight in the name of grass? Young men who raid cattle-camps— You won’t get a wife that way. -

(SAFER) Project in South Sudan

(31 October 2019) Annual Report Project Name Sustainable Agriculture or Economic Resiliency (SAFER) project in South Sudan Implementation /Funding Mechanism (Cooperative Grant Agreement/ Contract /Grant) Activity Start/ End Date 4 August 2017 to 3 August 2020 Name of Prime Implementing Partner The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Name of Implementing Sub-Partner N/A Contract/Agreement Number Grant NO. AID-668-IO-17-00001 Geographical Location The Republic of South Sudan Prepared for USAID/South Sudan, Juba Brian Dusza /Lemi Lokosang C/O American Embassy, Kololo Road Reporting period 1 October 2018 to 30 September 2019 Financial Expenditure for the Reporting Period To be sent separately as agreed Submitted by: Meshack Malo [email protected] 1 Acronyms AAP Accountability to Affected Populations AGRA Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa CAAFAG Children Formerly Associated with Armed Groups CBAHW Community-based Animal Health Workers CBO Community Based Organisation CBPP Community-based Participatory Planning CLA Collaboration, Learning and Adapting EMMP Environmental Monitoring and Mitigation Plan FES Fuel Efficient Stove FFS Farmer Field School GEFE Gender Equality and Female Empowerment GBV Gender-based Violence WPS Women Peace and Security IDP Internally Displaced Persons IOM International Organization for Migration LoA Letter of Agreement M&E Monitoring and Evaluation MEP Monitoring and Evaluation Plan NGO Non-Governmental Organization NPA Norwegian People’s Aid NBeG Northern Bahr el Ghazal NRM -

SITREP#109 24Feb 2017Final

Republic of South Sudan Situation Report #109 on Cholera in South Sudan As at 23:59 Hours, 24 February 2017 Situation Update A total of 13 counties in 9 (28%) of 32 states countrywide have confirmed cholera outbreaks (Table 1; Figure 1.0). The most recent cases were confirmed in Yirol East, Eastern Lakes state on 22 February 2017. Suspect cholera cases have been reported in Malakal Town; Pajatriei Islands, Bor county; Panyagor, Twic East county; and Moldova Islands, Duk county (Table 4). During week 8 of 2017, a total of 4 samples from Yirol East and 2 samples from Mayendit tested positive for cholera (Table 3). Cumulatively, 185 (37.8 %) samples have tested positive for Vibrio Cholerae inaba in the National Public Health Laboratory as of 24 February 2017 (Table 3). Table 1: Summary of cholera cases reported in South Sudan as of 24 February 2017 New New Total cases Total Reporting New deaths Total facility Total cases admissions discharges currently community Total deaths Total cases Sites WK 8 deaths discharged WK 8 WK 8 admitted deaths Jubek – Juba - - - - 8 19 27 2,018 2,045 Jonglei-Duk - - - - 3 5 8 92 100 Jonglei-Bor - 15 - 7 1 3 4 51 62 Terekeka - - - - - 8 8 14 22 Eastern Lakes 12 5 - 5 2 8 10 478 493 - Awerial Eastern Lakes 1 5 - 1 5 12 17 176 194 - Yirol East Imatong - - - - - - 1 1 28 29 Pageri Western Bieh - - - - - 4 - 4 266 270 Fangak Northern Liech - - - - 3 7 2 9 1,144 1,156 Rubkona Southern - - - - 3 - 3 91 94 Liech - Leer Southern Liech - - - - - 17 4 21 435 456 Panyijiar Southern Liech - 2 2 - - - 5 5 214 219 Mayendit Central Upper 5 181 Nile - Pigi 3 2 3 5 173 Total 18 29 - 19 55 67 122 5,180 5,321 Highlights in week 8 of 2017: 1. -

Country Profiles

Global Coalition EDUCATION UNDER ATTACK 2020 GCPEA to Protect Education from Attack COUNTRY PROFILES SOUTH SUDAN A peace agreement signed between the government and main opposition groups and enacted in September 2018 contributed to a decrease in violence in South Sudan. However, attacks on education continued to occur during this reporting period, including the use of schools by armed forces and groups, attacks on schools, attacks on students and teachers, and sexual violence at schools. Context Fighting de-escalated between the pro-Riek Machar Sudan People’s Liberation Army in Opposition (SPLA-IO (RM)) and the government’s South Sudan People’s Defense Forces (SSPDF) preceding and following the signing of the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS) in September 2018.1799 According to International Crisis Group (ICG), armed conflict noticeably declined in former areas of hostilities such as Bentiu, Wau, and Yei.1800 However, violence escalated again in late 2018 and early 2019 between signatories and non-signatories to the agreement, including the National Salvation Front (NAS) in Central Equatoria state and the Greater Bahr el Ghazal region, in addition to continued intercommunal violence.1801 Violence during the 2017-2019 reporting period occurred in the context of a civil war that erupted in 2013 when a power struggle between President Salva Kiir, of the majority Dinka ethnic group, and former vice-president Riek Machar, of the Nuer ethnic group, triggered ethnically-charged violence between government armed forces and the SPLA-IO (RM), and other affiliatedmilitias and local self-defense groups.1802 Civilians were impacted by the fighting during the 2017-2019 reporting period. -

Viable Support to Transition and Stability (Vistas) Q1 Fy 2019 Quarterly Report October 1 – December 31, 2018

VIABLE SUPPORT TO TRANSITION AND STABILITY (VISTAS) Q1 FY 2019 QUARTERLY REPORT OCTOBER 1 – DECEMBER 31, 2018 January 21, 2019 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by AECOM. VIABLE SUPPORT TO TRANSITION AND STABILITY (VISTAS) Q1 FY 2019 QUARTERLY REPORT OCTOBER 1– DECEMBER 31, 2018 Contract No. AID-668-C-13-00004 Submitted to: USAID South Sudan Prepared by: AECOM International Development Prepared for: Office of Transition and Conflict Mitigation (OTCM), USAID South Sudan Mission American Embassy Juba, South Sudan DISCLAIMER: The authors’ views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Q1 FY 2019 Quarterly Report | Viable Support to Transition and Stability (VISTAS) i TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms .................................................................................................................................... iii I. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 1 Ii. Political And Security Landscape ................................................................................... 2 Iii. Program Strategy ............................................................................................................ 3 Iv. Program Highlights ......................................................................................................... 5 To Increase -

Discover the Country Profile of South Sudan

COUNTRY PROFILE SOUTH SUDAN photo Nicola Berti SNAP- A 69-YEARS DOCTORS SHOT HISTORY WITH AFRICA Doctors with Africa CUAMM is 1,800 currently People have left CUAMM operating in Italy and other Angola, Central countries to work African Republic, on projects: Ethiopia, of these, Mozambique, 515 returned Sierra Leone, on one or more South Sudan, occasions Tanzania and Uganda through: 227 Hospitals have 23 been served Hospitals 01 42 08 02 03 64 Countries Districts of intervention 04 (for public health activities, mother-child 05 care, fight against AIDS, 06 tuberculosis 07 and malaria, 01 SIERRA LEONE training) 02 SOUTH SUDAN 03 ETHIOPIA 04 UGANDA 3 05 TANZANIA Nursing 06 ANGOLA schools 07 MOZAMBIQUE 08 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC 1 University Doctors with Africa CUAMM (Mozambique) has been the first NGO working VALUES in the international health field – «With Africa»: to be recognized in Italy and the organization works 605 is the largest Italian organization exclusively with African International for the promotion and protection populations, engaging Professionals of health in Africa. It works with local human resources a long-term developmental at all levels. perspective. To this end, in Italy – Experience: CUAMM and Africa, it is engaged in training, draws on over almost research, dissemination of scientific seventy years of work to knowledge, and ensuring support developing the universal fulfilment of the countries. fundamental human right to health. – Specific, exclusive expertise in medicine Doctors with Africa is for everyone and health. who believes in values like dialogue, cooperation, volunteerism, exchange between cultures, friendship between PRIORITY people, the defense of human rights, respect for life, the choice to help ISSUES the poor, the spirit of service, and – Reproductive, maternal, those who support the organization’s newborn, child and action criteria. -

UNICEF South Sudan Humanitarian Situation July 2019

UNICEF SOUTH SUDAN SITUATION REPORT JULY 2019 A health worker is trained on infection prevention and control in the context of Ebola, as part of UNICEF and South South Sudan’s Ebola prevention and preparedness efforts. Photo: UNICEF South Sudan/Wilson Sudan Humanitarian Situation Report JULY 2019: SOUTH SUDAN SITREP #134 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 1.83 million • In July 2019, UNICEF in collaboration with the Ministry of Health Internally displaced persons (IDPs) (national and state levels), WHO and other partners continued to create (OCHA South Sudan Humanitarian Snapshot, July 2019) awareness, engage and sensitize communities on Ebola in high-risk states reaching 208,669 people (101,938 men; 106,731 women). • On 23 July, 32 children were released from pro-Machar SPLA-iO in 2.32 million South Sudanese refugees in Mirmir, Unity State. All children were reunited with their families and are receiving reintegration services including comprehensive case neighbouring countries (UNHCR Regional Portal, South Sudan Situation management. 31 July 2019) • 26 July marked National Girls’ Education Day. In Juba, the event was hosted by the Jubek State Ministry of Education along with education 6.87 million partners. Approximately 1,085 girls from 15 schools took part in a rally South Sudanese facing acute food which included dance, drama, songs and poetry performances. insecurity or worse (May-July 2019 Projection, Integrated Food Security Phase Classification) UNICEF’s Response with Partners in 2019 Cluster for 2019 UNICEF and partners for 2019