Report of the Workshop for the Development of a National Strategy for Incorporating Traditional Knowledge Into Development Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatial Dimensions of Conflict-Induced Internally Displaced Population in the Puttalam District of Sri Lanka from 1980 to 2012 Deepthi Lekani Waidyasekera

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects 12-1-2012 Spatial Dimensions of Conflict-Induced Internally Displaced Population in the Puttalam District of Sri Lanka from 1980 to 2012 Deepthi Lekani Waidyasekera Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Waidyasekera, Deepthi Lekani, "Spatial Dimensions of Conflict-Induced Internally Displaced Population in the Puttalam District of Sri Lanka from 1980 to 2012" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 668. https://commons.und.edu/theses/668 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPATIAL DIMENSIONS OF CONFLICT-INDUCED INTERNALLY DISPLACED POPULATION IN THE PUTTALAM DISTRICT OF SRI LANKA FROM 1980 TO 2012 by Deepthi Lekani Waidyasekera Bachelor of Arts, University of Sri Jayawardanapura,, Sri Lanka, 1986 Master of Science, University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka, 2001 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota In partial fulfilment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota December 2012 Copyright 2012 Deepthi Lekani Waidyasekera ii PERMISSION Title Spatial Dimensions of Conflict-Induced Internally Displaced Population in the Puttalam District of Sri Lanka from 1980 to 2012 Department Geography Degree Master of Arts In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the library of the University shall make it freely available for inspection. -

Ruwanwella) Mrs

Lady Members First State Council (1931 - 1935) Mrs. Adline Molamure by-election (Ruwanwella) Mrs. Naysum Saravanamuttu by-election (Colombo North) (Mrs. Molamure was the first woman to be elected to the Legislature) Second State Council (1936 - 1947) Mrs. Naysum Saravanamuttu (Colombo North) First Parliament (House of Representatives) (1947 - 1952) Mrs. Florence Senanayake (Kiriella) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena by-election (Avissawella) Mrs. Tamara Kumari Illangaratne by-election (Kandy) Second Parliament (House of (1952 - 1956) Representatives) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena (Avissawella) Mrs. Doreen Wickremasinghe (Akuressa) Third Parliament (House of Representatives) (1956 - 1959) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene (Colombo North) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena (Kiriella) Mrs. Vimala Wijewardene (Mirigama) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna by-election (Welimada) Lady Members Fourth Parliament (House of (March - April 1960) Representatives) Mrs. Wimala Kannangara (Galigomuwa) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Soma Wickremanayake (Dehiowita) Fifth Parliament (House of Representatives) (July 1960 - 1964) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Soma Wickremanayake (Dehiowita) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene by-election (Borella) Sixth Parliament (House of Representatives) (1965 - 1970) Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Mrs. Sivagamie Obeyesekere (Mirigama) Mrs. Wimala Kannangara (Galigomuwa) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Leticia Rajapakse by-election (Dodangaslanda) Mrs. Mallika Ratwatte by-election (Balangoda) Seventh Parliament (House of (1970 - 1972) / (1972 - 1977) Representatives) & First National State Assembly Mrs. Kusala Abhayavardhana (Borella) Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene (Dehiwala - Mt.Lavinia) Lady Members Mrs. Tamara Kumari Ilangaratne (Galagedera) Mrs. Sivagamie Obeyesekere (Mirigama) Mrs. Mallika Ratwatte (Balangoda) Second National State Assembly & First (1977 - 1978) / (1978 - 1989) Parliament of the D.S.R. of Sri Lanka Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Miss. -

Fit.* IRRIGATION and MULTI-PURPOSE DEVELOPMENT

fit.* The Historic Jaya Ganga — built by King Dbatustna in tbi <>tb century AD to carry the waters of the Kala Wewa to the ancient city tanks of Anuradbapura, 57 miles away, while feeding a number of village tanks in its course. This channel is also famous for the gentle gradient of 6 ins. per mile for the first I7 miles and an average of 1 //. per mile throughout its length. Both tbeKalawewa andtbefiya Garga were restored in 1885 — 18 8 8 by the British, but not to their fullest capacities. New under the Mabaweli Diversion project, the Kill Wewa his been augmented and the Jaya Gingi improved to carry 1000 cusecs of water. The history of our country dates back to the 6th century B.C. When the legendary Vijaya landed in L->nka, he is believed to have found an island occupied by certain tribes who had already developed a rudimentary sys tem of irrigation. Tradition has it that Kuveni was spinning cotton on the bund of a small lake which was presumably part of this ancient system. The development of an ancient civilization which was entirely depen dent on an irrigation system that grew in size and complexity through the years is described in our written history. Many examples are available which demonstrate this systematic development of water and land re sources throughout the so-called dry zone of our country over very long periods of time. The development of a water supply and irrigation system around the city of Anuradhapuia may be taken as an example. -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

A Strategy for Nature Tourism Management

I I I A STRATEGY FOR NATURE TOURISM I MANAGEMENT: I Review of the EnvIronmental and Economic Benefits I of Nature TourIsm and Measures to Increase these Benefits I By I H M 8 C Herath M Sivakumar I P Steele I FINAL REPORT I August 1997 I Prepared for the Ceylon Tourrst Board and Department of Wildlife I USAIDI Natural Resources & Environmental Polley Project International Resources Group (NAREPP/IRG) I A project of the United States Agency for International Development and the I Government of Sri Lanka I I I I I I I DlScriptlOllS about Authors Mr HMC Herath IS a Deputy DIrector workIng for Department of WIldlIfe I ConservatIon, 18, Gregory's Road, Colombo 07, TP No 94-01-695 045 Mr M Sivakurnar IS a Research asSIStant, EnvIronmental DIvISIon Mmistry of I Forestry and EnvIronment, 3 rd Floor, Umty Plaza Bmldmg, Colombo 04 Mr Paul Steele IS an EconomIC Consultant workIng for EnvIronmental DIvISIon, I MllliStry of Forestry and EnvIronment, 3 rd Floor, Umty Plaza BUlldmg, Colombo 04 I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I CONTENTS I Page I Executive Summary 1-11 1 IntroductIOn 12 I 2 EXIstmg market for nature tounsm 13-19 I 3 Survey of eXIstIng nature tounsm sItes 20-35 4 EnvIronmental and economIC ObjectIves of a I nature tounsm management strategy 36-42 5 QuantIfymg the economiC benefits from nature tounsm 43-56 I 6 ActI\ ltles and SItes for dIversIfymg and expandIng nature tounsm 57-62 I 7 ConclUSIOns and RecommendatIons for IncreasIng the e'1\ Ironmental and economIC benefits of I nature tounsm 63-65 8 References 66 I 9 Annex 1 LIst of persons consulted 67-68 I Annex 2 Graphs of VIsItor entrance and revenues 69-77 Annex 3 Summary of RecommendatIons of Nature Tounsm Workshop and LISt I of PartIcipants 78-80 I I I I I I I Executive summary I 1 Nature tOUrIsm should be promoted by the Ceylon TourlSt Board to mcrease the number of tourlSts vlSlt10g Sn Lanka. -

Index No Marks Sex Med Name 2200015 041 F 2200023 040 F 2200031 047 F 2200040 049 M 2200058 046 F 2200066 028 M 2200074 042 F 22

INDEX NO MARKS SEX MED NAME ADDRESS POSTAL ADDRESS 2200015 041 F SIN WASANTHI, M.K. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, THIHAGODA. 2200023 040 F SIN KUMUDINI, E.V.S. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, THIHAGODA. 2200031 047 F SIN WICKRAMASINGHE, W.M.K.P. DIVISIONAL SECRETARY OFFICE, UKUWELA. 2200040 049 M SIN BANDULA, B.G. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, UKUWELA. 2200058 046 F SIN SAMARATHUNGE, S.M.N.R.K. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, UKUWELA. 2200066 028 M SIN ABULASIN, S. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, UKUWELA. 2200074 042 F SIN RANASINGHE, M.G.C. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, UKUWELA. 2200082 040 F SIN MALIMAGE, G.M.P.S. A.G.A. OFFICE, KOLONNAWA. 2200090 044 M SIN PREMALAL, A.A.D.K. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, KOLONNAWA. 2200104 042 F SIN GURUGE, I. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, KOLONNAWA. 2200112 037 F SIN VIOLET, V.D.R. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, KOLONNAWA. 2200120 051 F SIN BANNEHEKA, B.M.W.K. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, ANAMADUWA. 2200139 044 F SIN HERATH, I.M.N.S.K. DISTRICT SECRETARIAT, SAMURDHI OFFICE, KURUNEGALA. 2200147 053 M SIN WIJESOORIYA, K.D.G. DISTRICT SECRETARIAT, KURUNEGALA. 2200155 046 M SIN CHAMINDA, K.M.R. SAMURDHI MANAGER, DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, PASSARA. 2200163 055 F SIN HETTIGE, D.H.S.L. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, PASSARA. 2200171 066 F SIN KARUNAWATHI, J.M. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, PASSARA. 2200180 053 F SIN DUNUSINGHE, P.N. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, PASBAGE KORALE, NAWALAPITIYA. 2200198 060 F SIN SAMUDDIKA, W.P.N. DIVISIONAL SECERATARIAT, PASBAGE KORALE, NAWALAPITIYA. 2200201 042 M SIN RANAWEERA, K.S. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, PASBAGE KORALE, NAWALAPITIYA. 2200228 041 F SIN INDRASEELI, K.M.N. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, IMBULPE. 2200236 045 F SIN UDAGALADENIYA, S.M.I. -

Multi-Decadal Forest-Cover Dynamics in the Tropical Realm: Past Trends and Policy Insights for Forest Conservation in Dry Zone of Sri Lanka

Article Multi-Decadal Forest-Cover Dynamics in the Tropical Realm: Past Trends and Policy Insights for Forest Conservation in Dry Zone of Sri Lanka Manjula Ranagalage 1,2,* , M. H. J. P. Gunarathna 3 , Thilina D. Surasinghe 4 , Dmslb Dissanayake 2 , Matamyo Simwanda 5 , Yuji Murayama 1 , Takehiro Morimoto 1 , Darius Phiri 5 , Vincent R. Nyirenda 6 , K. T. Premakantha 7 and Anura Sathurusinghe 7 1 Faculty of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Tsukuba, 1-1-1, Tennodai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8572, Japan; [email protected] (Y.M.); [email protected] (T.M.) 2 Department of Environmental Management, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, Mihintale 50300, Sri Lanka; [email protected] 3 Department of Agricultural Engineering and Soil Science, Faculty of Agriculture, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, Anuradhapura 50000, Sri Lanka; [email protected] 4 Department of Biological Sciences, Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, MA 02325, USA; [email protected] 5 Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, School of Natural Resources, Copperbelt University, P.O. Box 21692, Kitwe 10101, Zambia; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (D.P.) 6 Department of Zoology and Aquatic Sciences, School of Natural Resources, Copperbelt University, Kitwe 10101, Zambia; [email protected] 7 Forest Department, Ministry of Environment and Wildlife Resources, 82, Rajamalwatta Road, Battaramulla 10120, Sri Lanka; [email protected] (K.T.P.); [email protected] (A.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 June 2020; Accepted: 28 July 2020; Published: 1 August 2020 Abstract: Forest-cover change has become an important topic in global biodiversity conservation in recent decades because of the high rates of forest loss in different parts of the world, especially in the tropical region. -

Fisheries Management Provisions

FISHERIES INSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS AND CAPACITY ASSESSMENT TO THE MINISTRY OF FISHERIES AND AQUATIC RESOURCES, SRI LANKA APPENDIX I: Fisheries Management provisions Table I.1: Fisheries co-management principles Participatory Fisheries Resource Meaning Management Principles The spirit of governance and administration are the interests of the people of Sri Lanka, based on their own aspirations. Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Under decentralization of the fisheries management process, DFAR and the District Fisheries Offices are the responsible Resources is responsible for facilitating the stakeholders: the decision-makers. Hence, these regional fisheries agencies are also responsible for facilitating the management of national and coastal fisheries management of regional fisheries resources by providing human and financial resources to support PFRM as a resources. framework for the management of regional and national fisheries resources. Stakeholders are the participants of fisheries management. The spirit of decentralization of decision-making is that stakeholders should decide on how their aspirations can be met. Stakeholders include: fishermen using different gear types; fish traders; fish processors; fisheries scientists and researchers; coastal communities; fish and plant farmers; district fisheries agencies and the central and district government fisheries agency (DFAR). Stakeholders of participatory coastal fisheries resource management are the coastal The selection of the appropriate stakeholder groups, to be involved in fisheries resource management, should be carried communities, private sectors and government out through stakeholder analysis and the best people to represent these groups chosen democratically. Stakeholder agencies. representatives must have the confidence of the group they represent to ensure ownership of decisions and the empowerment of the stakeholder groups. The social and cultural differences of stakeholders should be formally accepted as input into the decision making process. -

Buddhist Forest Monasteries and Meditation Centres in Sri Lanka a Guide for Foreign Buddhist Monastics and Lay Practitioners

Buddhist Forest Monasteries and Meditation Centres in Sri Lanka A Guide for Foreign Buddhist Monastics and Lay Practitioners Updated: April 2018 by Bhikkhu Nyanatusita Introduction In Sri Lanka there are many forest hermitages and meditation centres suitable for foreign Buddhist monastics or for experienced lay Buddhists. The following information is particularly intended for foreign bhikkhus, those who aspire to become bhikkhus, and those who are experienced lay practitioners. Another guide is available for less experienced, short term visiting lay practitioners. Factors such as climate, food, noise, standards of monastic discipline (vinaya), dangerous animals and accessibility have been considered with regard the places listed in this work. The book Sacred Island by Ven. S. Dhammika—published by the BPS—gives exhaustive information regarding ancient monasteries and other sacred sites and pilgrimage places in Sri Lanka. The Amazing Lanka website describes many ancient monasteries as well as the modern (forest) monasteries located at the sites, showing the exact locations on satellite maps, and giving information on the history, directions, etc. There are many monasteries listed in this guides, but to get a general idea of of all monasteries in Sri Lanka it is enough to see a couple of monasteries connected to different traditions and in different areas of the country. There is no perfect place in samṃsāra and as long as one is not liberated from mental defilements one will sooner or later start to find fault with a monastery. There is no monastery which is perfectly quiet and where the monks are all arahants. Rather than trying to find the perfect external place, which does not exist, it is more realistic to be content with an imperfect place and learn to deal with the defilements that come up in one’s mind. -

Polonnaruwa Development Plan 2018-2030

POLONNARUWA URBAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2018-2030 VOLUME I Urban Development Authority District Office Polonnaruwa 2018-2030 i Polonnaruwa 2018-2030, UDA Polonnaruwa Development Plan 2018-2030 POLONNARUWA URBAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN VOLUME I BACKGROUND INFORMATION/ PLANNING PROCESS/ DETAIL ANALYSIS /PLANNING FRAMEWORK/ THE PLAN Urban Development Authority District Office Polonnaruwa 2018-2030 ii Polonnaruwa 2018-2030, UDA Polonnaruwa Development Plan 2018-2030 DOCUMENT INFORMATION Report title : Polonnaruwa Development Plan Locational Boundary (Declared area) : Polonnaruwa MC (18 GN) and Part of Polonnaruwa PS(15 GN) Gazette No : Client/ Stakeholder (shortly) : Local Residents, Relevent Institutions and Commuters Commuters : Submission date :15.12.2018 Document status (Final) & Date of issued: Author UDA Polonnaruwa District Office Document Submission Details Version No Details Date of Submission Approved for Issue 1 Draft 2 Draft This document is issued for the party which commissioned it and for specific purposes connected with the above-captioned project only. It should not be relied upon by any other party or used for any other purpose. We accept no responsibility for the consequences of this document being relied upon by any other party, or being used for any other purpose, or containing any error or omission which is due to an error or omission in data supplied to us by other parties. This document contains confidential information and proprietary intellectual property. It should not be shown to other parties without consent from the party -

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

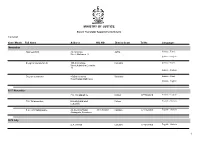

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka Report

Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka A multi-agency approach coordinated by Central Environment Authority and Disaster Management Centre, Supported by United Nations Development Programme and United Nations Environment Programme Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka November 2014 A Multi-agency approach coordinated by the Central Environmental Authority (CEA) of the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy and Disaster Management Centre (DMC) of the Ministry of Disaster Management, supported by United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Integrated Strategic Environment Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka ISBN number: 978-955-9012-55-9 First edition: November 2014 © Editors: Dr. Ananda Mallawatantri Prof. Buddhi Marambe Dr. Connor Skehan Published by: Central Environment Authority 104, Parisara Piyasa, Battaramulla Sri Lanka Disaster Management Centre No 2, Vidya Mawatha, Colombo 7 Sri Lanka Related publication: Map Atlas: ISEA-North ii Message from the Hon. Minister of Environment and Renewable Energy Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is a systematic decision support process, aiming to ensure that due consideration is given to environmental and other sustainability aspects during the development of plans, policies and programmes. SEA is widely used in many countries as an aid to strategic decision making. In May 2006, the Cabinet of Ministers approved a Cabinet of Memorandum