E MISCELLANY' * L)],1:\/ LT .UU,\ Ir J(R)T I T Bt \7 *.-T 'F, Tfilnr1,:.'13- Ttu"T$ -T,Ij \

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOME NOTES on the FAMILY HISTORY of NICHOLAS LONGFORD, SHERIFF of LANCASHIRE in 1413. the Subject of This Paper Is the Family Hi

47 SOME NOTES ON THE FAMILY HISTORY OF NICHOLAS LONGFORD, SHERIFF OF LANCASHIRE IN 1413. By William Wingfield Longford, D.D., Rector of Sefton. Read March 8, 1934. HE subject of this paper is the family history of T Sir Nicholas Longford of Longford and Withington, in the barony of Manchester, who appears with Sir Ralph Stanley in the roll of the Sheriffs of Lancashire in the year 1413. He was followed in 1414, according to the Hopkinson MSS., by Robert Longford. This may be a misprint for Sir Roger Longford, who was alive in Lan cashire in 1430, but of whom little else is known except that he was of the same family. Sir Nicholas Longford was a knight of the shire for Derbyshire in 1407, fought at Agincourt and died in England in 1416. It might be thought that the appearance of this name in the list of sheriffs on two occasions only, with other names so more frequent and well known from the reign of Edward III onwards Radcliffe, Stanley, Lawrence, de Trafford, Byron, Molyneux, Langton and the rest de.ioted a family of only minor importance, suddenly coming into prominence and then disappearing. But such a con clusion would be ill-founded. The Longford stock was of older standing than any of them, and though the Stanleys rose to greater fame and based their continuance on wider foundations, at the point when Nicholas Long ford comes into the story, the two families were of equal footing and intermarried. Nicholas Longford's daughter Joan was married to John Stanley, son and heir of Sir John Stanley the second of Knowsley. -

Part 1.7 Trent Valley Washlands

Part One: Landscape Character Descriptions 7. Trent Valley Washlands Landscape Character Types • Lowland Village Farmlands ..... 7.4 • Riverside Meadows ................... 7.13 • Wet Pasture Meadows ............ 7.9 Trent Valley Washlands Character Area 69 Part 1 - 7.1 Trent Valley Washlands CHARACTER AREA 69 An agricultural landscape set within broad, open river valleys with many urban features. Landscape Character Types • Lowland Village Farmlands • Wet Pasture Meadows • Riverside Meadows "We therefore continue our course along the arched causeway glancing on either side at the fertile meadows which receive old Trent's annual bounty, in the shape of fattening floods, and which amply return the favour by supporting herds of splendid cattle upon his water-worn banks..." p248 Hicklin; Wallis ‘Bemrose’s Guide to Derbyshire' Introduction and tightly trimmed and hedgerow Physical Influences trees are few. Woodlands are few The Trent Valley Washlands throughout the area although The area is defined by an constitute a distinct, broad, linear occasionally the full growth of underlying geology of Mercia band which follows the middle riparian trees and shrubs give the Mudstones overlain with a variety reaches of the slow flowing River impression of woodland cover. of fluvioglacial, periglacial and river Trent, forming a crescent from deposits of mostly sand and gravel, Burton on Trent in the west to Long Large power stations once to form terraces flanking the rivers. Eaton in the east. It also includes dominated the scene with their the lower reaches of the rivers Dove massive cooling towers. Most of The gravel terraces of the Lowland and Derwent. these have become Village Farmlands form coarse, decommissioned and will soon be sandy loam, whilst the Riverside To the north the valley rises up to demolished. -

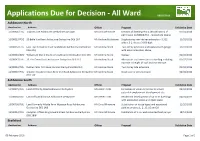

Applications Due for Decision - All Ward 08/02/2016

Applications Due for Decision - All Ward 08/02/2016 Ashbourne North Application Address Officer Proposal Validation Date 15/00926/FUL 1 Spire Close Ashbourne Derbyshire DE6 1DB Mr Chris Whitmore Erection of dwelling Plot 1 (Modification) of 07/01/2016 permission 12/00606/FUL - revised site levels) 16/00019/PDE 59 Belle Vue Road Ashbourne Derbyshire DE6 1AT Mr Andrew Ecclestone Single storey rear kitchen extension - 3.312 11/01/2016 wide x 3.2. deep x 3.000 high 16/00032/FUL Low Top 35 Buxton Road Sandybrook Ashbourne Derbyshire Mr Andrew Stock Two storey extension and replacement garage 25/01/2016 DE6 2AQ with accommodation above 16/00065/ADV Williams & Glyn 2 Dig Street Ashbourne Derbyshire DE6 1GS Mr Andrew Stock Signage 01/02/2016 16/00047/FUL 35 The Green Road Ashbourne Derbyshire DE6 1ED Mr Andrew Stock Alterations and extensions to dwelling including 01/02/2016 increase in height of roof and rear terrace 16/00051/FUL Nether Farm Mill Lane Sturston Derbyshire DE6 1LN Mr Andrew Stock Two storey side extension 01/02/2016 16/00067/FUL 1 Queen Elizabeth Court Belle Vue Road Ashbourne Derbyshire Mr Andrew Stock Single storey side extension 02/02/2016 DE6 1NE Ashbourne South Application Address Officer Proposal Validation Date 14/00075/FUL Land Off Derby Road Ashbourne Derbyshire Mrs Helen Frith Formation of vehicular access to service 06/02/2014 potential employment development site 15/00060/OUT Land Off Lathkill Drive Ashbourne Derbyshire Mrs Helen Frith Residential development of up to 35 dwellings 04/02/2015 with associated access and open space 15/00736/FUL Land Formerly Hillside Farm Wyaston Road Ashbourne Mr Chris Whitmore Substitution of house types and associated 12/10/2015 Derbyshire DE6 1NB parking on plots 1, 2, 15, 16 and 20 15/00913/FUL Compton Offices King Edward Street Ashbourne Derbyshire Mr Chris Whitmore Installation of 2 no. -

Sunday, 18 July 2021 Psalter Week 4 Our Lady of Beauchief & Saint

Our Lady of Beauchief & Saint Thomas of Canterbury Meadowhead, Sheffield, S8 7UD Telephone: 0114 274 7257 Email: [email protected] Website: www.olstsheffield.org.uk Chapel of Ease: English Martyrs, Baslow Road, Totley S17 4DR Parish Priest: Father Stephen Ssekiwunga St Thomas of Canterbury Catholic Primary School Chancet Wood Drive, Sheffield S8 7TR Telephone: 0114 274 5597 Email: enquiries@st -tc.co.uk Website: www.st -tc.co.uk The Month of July is devoted to the Precious Blood of Jesus Sixteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time (B) Sunday, 18 July 2021 Psalter Week 4 Saturday Next week’s Masses 5.00 p.m. (Totley) People of the Parish Saturday (Totley) 5.00 p.m. People of the Parish Sunday Sunday (Meadowhead) 9.15 a.m. Eduardo Ross 9.15 a.m. World Day for Grandparents 11.15 a.m. Harry & Minnie Richardson and the Elderly Feria 11.15 a.m. Joe & Philomena McNally Monday 50th Wedding Anniversary No Mass Brenda Desmond RIP Please Pray for: Tuesday (Totley) St Apollinaris, bishop, martyr Our sick: Pam McDonald, Doreen 10.00 a.m. Wilde, Tony Faulkner, Danny Grant, Mary & David Gage, Franco Anobele, Wednesday St Laurence of Brindisi Angela McKinney, David Hague, Pauline 10.00 a.m. Danny Grant Souflas, Teddy Howes, Katie Glackin, Neville Garratt, Michael Goodfellow, Thursday ST MARY MAGDALEN Pauline Collins, Marie Lennox, Rae No Mass Goodlad, Linda Costello, Edward Keefe and Sr Emma Bechold. Friday ST BRIDGET OF SWEDEN PATRON OF EUROPE Lately Dead: Fr Liam Smith And let us remember in our prayers No Mass Zisimos Souflas who is missing. -

The Livery Collar: Politics and Identity in Fifteenth-Century England

The Livery Collar: Politics and Identity in Fifteenth-Century England MATTHEW WARD, SA (Hons), MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy AUGUST 2013 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, lS23 7BQ www.bl.uk ANY MAPS, PAGES, TABLES, FIGURES, GRAPHS OR PHOTOGRAPHS, MISSING FROM THIS DIGITAL COPY, HAVE BEEN EXCLUDED AT THE REQUEST OF THE UNIVERSITY Abstract This study examines the social, cultural and political significance and utility of the livery collar during the fifteenth century, in particular 1450 to 1500, the period associated with the Wars of the Roses in England. References to the item abound in government records, in contemporary chronicles and gentry correspondence, in illuminated manuscripts and, not least, on church monuments. From the fifteenth century the collar was regarded as a potent symbol of royal power and dignity, the artefact associating the recipient with the king. The thesis argues that the collar was a significant aspect of late-medieval visual and material culture, and played a significant function in the construction and articulation of political and other group identities during the period. The thesis seeks to draw out the nuances involved in this process. It explores the not infrequently juxtaposed motives which lay behind the king distributing livery collars, and the motives behind recipients choosing to depict them on their church monuments, and proposes that its interpretation as a symbol of political or dynastic conviction should be re-appraised. After addressing the principal functions and meanings bestowed on the collar, the thesis moves on to examine the item in its various political contexts. -

North Staffordshire Field Club, Transactions and Annual Report, 1937, Volume LXXI

Staffordshire SampleCounty Studies THE NORTH STAFFORDSHIRE StaffordshireFIELD CLUB, TRANSACTIONS AND A n n u a l R e p o r t 1936- 37. SampleEDITEDCounty BY H. V. THOMPSON, M.A. Studies VOL. LXXI. Published by the North Staffordshire Field Club, Stoke-on-Trent. STAFFORD: AM/ISON & BOWEN. Ltd . J 937- COPYRIGHT. CONTENTS P age Council and Com mittees for 1936-37 ______ 4 StaffordshireAccounts ------------ - 7 Annual R eport 10 Congress of Arclueological Societies—Miss H. L. Tv. Garbett - 12 Anglo-American Conference of Historians—1'. Pape, M.A., P.S.A. 15 ADDRESSES AND PAPERS. Presidential Address—Miss M. S. Bickley, B.A. - 20 William Adams, 1736—1802—P. W. D. Adams, F.S.A. - 23 Dovedalc and Manifold Valley Properties of the National Trust —F. A. Holmes, F.R.G.S. - - - - - - - - 26 In Memoriam, Revd. E. Deacon, B.A.—W. T. Boydon Ridge, B.Se. ____________ 33 SampleREPORTS OF SECTIONS. A. Zoology.—B. Bryan _ ________County 35 B. Entomology.—H. W. Daltry, F.R.E.S. ----- 43 C. Botany.—W. T. Boydon Ridge, B.Sc. - 48 E. Geology.—F. W. Dennis, F.G.S. 49 P. Meteorology.—Graham C. Lawson, F.R. Met. Soc. - - 53 G Archioology and History.—G. J. V. Bemrose - - - 66 JOURNAL OF PROCEEDINGS. Field Meetings - Studies- 68 Evening Meetings ---------- - 77 List of Members - - - - - - - - - - - 81 APPENDIX. T. Smith.—The Birds of Staffordshire, Part VIII. (pages A213 to A248) PLATES. I. W illiam Adams, 1736-—1802 ----- to face 23 II. Dovedale—National Trust Properties - - - ,,26 III. The Grounds, Ilam Hall ------ „ 28 IV. Wolfscote Dale: Hurts Wood and Hall Dale - „ 29 V. -

J31800 Micro Hydro Report

Appendix B LIST OF SITES ASSESSED BY GIS CONSTRAINTS MODEL SITE NO. AND NAME PAGE NO. SITE NO. AND NAME PAGE NO. B1 SITES WITHIN THE PDNP B2 NON-MILL SITES (ALL IN THE PDNP) M1 Ginclough Mill 80 N1 Bar Brook, near Baslow 160 M2 Alport Mill 82 N5 Padley Gorge, Grindleford 162 M3 Ashford Bobbin Mill 84 N10 Greenlands, Edale 164 M4 Flewitt’s Mill, Ashford 86 N15 Grinds Brook, Edale 166 M5 Lumford Mill, Bakewell 88 M6 Rutland Mill, Bakewell 90 B3 SITES OUTSIDE THE PDNP M7 Victoria Mill, Bakewell 92 O1 Waulk Mill, Bollington 168 M8 Bamford Mill, Bamford 94 O2 Hayfield weir 170 M9 Hodgkinson’s Mill, Baslow 96 O3 Hollingworth weir 172 M10 Blackwell Mill, Wye Dale 98 O4 Loxley River, Sheffield 174 M11 Butts Mill, Bradwell 100 O5 More Hall Reservoir 176 M12 Brough Mill, Brough 102 O6 Rivelin Dams, Sheffield 178 M13 Stretfield Mill, Bradwell 104 O7 Rivelin Valley East 180 M14 Calver Mill, Calver 106 O8 Rivelin Water Treatment Works 182 M15 Edensor Mill 108 O9 Bottoms weir, Holmfirth 184 M16 Cressbrook Mill 110 O10 Marsden town weir 186 M18 Crowden Paper Mill 112 O11 Rivelin Mill, Sheffield 188 M19 Padley Mill, Grindleford 114 O12 Bonsall (Via Gellia) Mill(s) 190 M20 Town Mill, Hartington 116 O13 Cromford Corn Mill 192 M21 Leadmill, near Hathersage 118 O14 Okeover 194 M22 Lumbhole Mill, Kettleshume 120 015 Millthorpe weir 196 M23 Old Saw Mill, Longnor 122 M24 Litton Mill 124 M25 Little Mill, Rowarth 126 M26 Caudwell’s Mill, Rowsley 128 M27 Dain’s Mill, Upper Hulme 130 M28 Wetton Mill 132 M29 Stoney Middleton Mill 134 M30 Diggle Mill, Saddleworth -

69: Trent Valley Washlands Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 69: Trent Valley Washlands Area profile: Supporting documents www.naturalengland.org.uk 1 National Character 69: Trent Valley Washlands Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper1, Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention3, we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform their decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. 1 The Natural Choice: Securing the Value of Nature, Defra NCA profiles are working documents which draw on current evidence and (2011; URL: www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/cm80/8082/8082.pdf) 2 knowledge. -

Appendix 9A: Gazetteer of Heritage Assets and Impacts

Appendix 9A: Gazetteer of Heritage Assets and Impacts HER / Listed Reference Magnitude of Building Reference Site name Description Designation Value Type of Impact Mitigation Significance of Effect number Impact Number Semi-detached house to north of Buxton Road with Shores - semi outbuilding to rear depicted on the 1850 tithe map. 1 MGM14184 detached house & Present buildings are two late 19th century semi- HER Low N/A N/A N/A No Impact outbuilding detached houses with adjoining gables facing Buxton Road Farmhouse range on west, with long brick-built outbuilding range on east along Threaphurst Lane. Shores Farm - 2 MGM1858 Farmhouse range includes late 19th/early 20th HER Low N/A N/A N/A No Impact Farmhouse century house on west; abutting this on east is earlier long lower range, South of Werneth Cluster of pit workings with spoil, pits approximately 3 MGM15653 View - Pit, Ridge and 15m wide spoil approximately 30m wide. Surrounded HER Low N/A N/A N/A No Impact Furrow, Spoil heap by ridge and furrow varying in width from 4m to 5m Coal mining was taking place in Norbury by 1707-8 when one pit was working and another was being Norbury Colliery - sunk. Mines then being worked by Peter Legh of 4 MGM643 Colliery, Engine Lyme, lord of Norbury manor. The colliery closed in HER Low N/A N/A N/A No Impact House, Industrial Site 1892 Site on east side of Norbury Hollow Road now occupied by Torkington Hall Dairy Three storeyed brick (timber, black and white cladding) tower with a pitched roof at the end of two Visual impact and Planting and Norbury Colliery adjoining 2 storey cottages, the clock still remains in 5 MGM1781 HER Low Minor impact on setting landscape Slight Adverse Clock House the gable of the tower. -

Recusant Literature Benjamin Charles Watson University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Gleeson Library Librarians Research Gleeson Library | Geschke Center 2003 Recusant Literature Benjamin Charles Watson University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.usfca.edu/librarian Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, History Commons, Library and Information Science Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Watson, Benjamin Charles, "Recusant Literature" (2003). Gleeson Library Librarians Research. Paper 2. http://repository.usfca.edu/librarian/2 This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Gleeson Library | Geschke Center at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gleeson Library Librarians Research by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECUSANT LITERATURE Description of USF collections by and about Catholics in England during the period of the Penal Laws, beginning with the the accession of Elizabeth I in 1558 and continuing until the Catholic Relief Act of 1791, with special emphasis on the Jesuit presence throughout these two centuries of religious and political conflict. Introduction The unpopular English Catholic Queen, Mary Tudor died in 1558 after a brief reign during which she earned the epithet ‘Bloody Mary’ for her persecution of Protestants. Mary’s Protestant younger sister succeeded her as Queen Elizabeth I. In 1559, during the first year of Elizabeth’s reign, Parliament passed the Act of Uniformity, declaring the state-run Church of England as the only legitimate religious authority, and compulsory for all citizens. -

Derbyshire Miscellany I

,t DERBYSHIRE MISCELLANY I The Local Hlstory Bulletln of the Derbychlre Archaeologlcal Soctety Volume 13 Spring L994 Part 5 DERBYSHIRE MISCELLANY Volume KII: Part 5 Spring 1994 CONTENTS Page Willian P atoel and F amily 110 by Barry Crisp Buildings on Swa*cstone Briilge 176 by Joan Baker The Ticknall Ro und H o us e 119 by Yvonne Crowden The tuimitioe Methodisl Clupel at Nwmanton-by-Detby 122 by Edward j. Wheadey Some Nditional Notes on Wlliam kuntofl,May 1777'Octobo 1857 124 by John Heath Tr.lo Victorhn Engineers with Dubyshire Origins 125 by John Heath Editoriat Note on 'ACommmtary on Recmt Work on the Morley Park 726 and Aldowasley honworks anil Coal Mines' DabyshireToobnakas 727 by Brian Read ASSISTANTEDITOR EDITOR TREASURER fane Steer Dudley Fowkes TJ. hrimore 4Zl Duffield Roa4 Staffordshlre Record Office ,B Reginald Road South Allestsee, EasBate Sbeet, Chaddesdetu D*by,DE222DJ sattofi,sT16ZLZ Derby DE21 5NG Copyright in each contribution to Derbyshire Misallazy is rcserved by the author. ISSI{ 0417 0687 109 WILLIAM PEVEREL AND FAMILY (by Barry Crisp, 5 Lark Hill, Swanwick, DE55 lDD) In Part 3 of Volume lI of Derbyshire Misellany for Spring 1%7 J.T . Leach related some of the limited information available about William Peverel somaime holder of the Honour of Pwerel of Nottingham. Since then the following additional details have been gleaned from other publications. Whilst these do not solve the basic question as to the origin of this first-noted Peverel they do suggest the probable relationships within the family in the years between the Conquest and the end of King Stephen's reign. -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames