252509413.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libertas Schulze-Boysen Und Die Rote Kapelle Libertas Schulze-Boysen Und Die Rote Kapelle

Libertas Schulze-Boysen und die Rote Kapelle Libertas Schulze-Boysen und die Rote Kapelle Der Großvater, Fürst Philipp Eulenburg zu Hertefeld, Familie genießt als Jugendfreund des Kaisers lange Zeit des- sen Vertrauen und gilt am Hofe als sehr einflussreich. und Nach öffentlichen Anwürfen wegen angeblicher Kindheit homosexueller Neigungen lebt der Fürst seit 1908 zurückgezogen in Liebenberg. Aus der Ehe mit der schwedischen Gräfin Auguste von Sandeln gehen sechs Kinder hervor. 1909 heiratet die jüngste Tochter Victoria den Modegestalter Otto Haas-Heye, einen Mann mit großer Ausstrahlung. Die Familie Haas- Heye lebt zunächst in Garmisch, dann in London und seit 1911 in Paris. Nach Ottora und Johannes kommt Libertas am 20. November 1913 in Paris zur Welt. Ihr Vorname ist dem „Märchen von der Freiheit“ entnom- men, das Philipp Eulenburg zu Hertefeld geschrieben hat. Die Mutter wohnt in den Kriegsjahren mit den Kindern in Liebenberg. 1921 stirbt der Großvater, und die Eltern lassen sich scheiden. Nach Privatunterricht in Liebenberg besucht Libertas seit 1922 eine Schule in Berlin. Ihr Vater leitet die Modeabteilung des Staatlichen Kunstgewerbemu- seums in der Prinz-Albrecht-Straße 8. Auf den weiten Fluren spielen die Kinder. 1933 wird dieses Gebäude Sitz der Gestapozentrale. Die Zeichenlehrerin Valerie Wolffenstein, eine Mitarbeiterin des Vaters, nimmt sich der Kinder an und verbringt mit ihnen den Sommer 1924 in der Schweiz. 4 Geburtstagsgedicht Es ist der Vorabend zum Geburtstag des Fürsten. Libertas erscheint in meinem Zimmer. Sie will ihr Kästchen für den Opapa fertig kleben[...] „Libertas, wie würde sich der Opapa freuen, wenn Du ein Gedicht in das Kästchen legen würdest!“ Sie jubelt, ergreift den Federhalter, nimmt das Ende zwischen die Lippen und läutet mit den Beinen. -

Widerstandsgruppe Schulze-Boysen/Harnack

Widerstandsgruppe Schulze-Boysen/Harnack Bearbeitet von Klaus Lehmann Herausgegeben von der zentralen Forschungsstelle der Vereinigung der Verfolgten des Naziregimes VVN Berliner Verlag GmbH, Berlin 1948, 88 Seiten Faksimileausgabe der Seiten 3 bis 27 und 86 bis 88 Die Schulze-Boysen/Harnack-Gruppe wurde 1942 von der Gestapo un- ter dem Begriff Rote Kapelle entdeckt und ausgeschaltet. Diese erste ausführliche Veröffentlichung erschien in der damaligen Sowjetischen Besatzungszone und wurde von der VVN, einer von der Sozialistischen Einheitspartei Deutschlands (SED) gelenkten Organisation, herausge- geben. Während die Widerstandsarbeit der Schulze-Boysen/Harnack-Gruppe mit Flugblättern, Zeitschriften, Klebeaktionen, Hilfe für politisch verfolg- te bis hin zur Beschaffung von Waffen beschrieben wird, wird ihre Spi- onagetätigkeit für die Sowjetunion bewusst verschwiegen. Die Spionagesender, die vom sowjetischen Nachrichtendienst zur Ver- fügung gestellt worden waren, werden hier stattdessen in Geräte um- gedeutet, die "mit ihren Sendungen das deutsche Volk" aufklären soll- ten (S.15). Dies zeigt, dass man sich zur Spionage für Stalin nicht be- kennen wollte, weil diese mit den damals gängigen moralischen Maß- stäben nicht in Einklang zu bringen war. Dies wandelte sich erst Ende der 1960-er Jahre, als die Sowjetunion einigen Mitgliedern der Roten Kapelle postum Militärorden verlieh und die DDR sie fortan als "Kundschafter" und Paradebeispiel für kommu- nistischen geführten Widerstand feierte. Auf den Seiten 28 bis 85 werden 55 Mitglieder -

Characters Interesting and Famous Among Leone's Acquaintances

Characters interesting and famous among Leone’s acquaintances. Roland Michener. Canadian statesman, MP, Governor-General, ambassador, Leone’s first date at the U of A and a lifelong friend. Dr. Egerton Pope. Leading professor in the U of A Faculty of Medicine who arrived for lectures in his chauffeur-driven limousine wearing a top hat, morning coat, striped trousers with spats over highly polished shoes, carrying his poodle. Dr. E.T. Bell. Leading pathologist of his time and Leone’s PhD advisor. Dr. Arthur Hertig. Harvard buddy and colleague who became a lifelong friend, later a professor of pathology who helped develop “The Pill”. Wolfgang Rittmeister. Scion of prominent Hamburg family, Leone’s main man until she met Folke Hellstedt in 1931. Lifelong friend, “uncle” to Leone’s son. Dr. John Rittmeister. Wolfgang’s brother, took lectures from Jung with Leone in Zürich, became a psychoanalyst and dept. head at the Göring Institut in Berlin. Active along with other members of the Rittmeister family in opposition to Nazis, including trying to get Jews out of Germany. Arrested for treason in in Berlin in 1942, guillotined in 1943. Wilda Blow. Opera singer from Calgary, studying in Milan, working in Hamburg. Matthew Halton. Foreign correspondent, “the voice of Canada” on radio during WW2, colleague of Ernest Hemingway on the Toronto Star, early opponent of Hitler and advocate of Churchill. Controversial U of A Gateway editor in 1928. Jean Halton. Matthew’s wife, also a U of A graduate. Jean and her sister Kathleen Campbell, from Lacombe, went with Leone on a scarcely believable three-month motoring trip through Europe and North Africa in 1934. -

Bibliographie Zur Geschichte Des Deutschen Widerstands Gegen Die NS-Diktatur 1938-1945

Karl Heinz Roth Bibliographie zur Geschichte des deutschen Widerstands gegen die NS-Diktatur 1938-1945 Stand: 20.7.2004 1.Veröffentlichte Quellen, Quellenübersichten, Quellenkritik, Dokumentationen und Ausstellungen AA. VV., Archivio Storico del Partito d´Azione. Istituto di Studi Ugo La Malfa, o.O. u.J. Ursula Adam (Hg.), “Die Generalsrevolte”. Deutsche Emigranten und der 20. Juli 1944, Eine Dokumentation, Berlin 1994 Ilse Aicher-Scholl (Hg.), Sippenhaft. Nachrichten und Botschaften der Familie in der Gestapo-Haft nach der Hinrichtung von Hans und Sophie Scholl, Frankfurt a.M. 1993 Peter Altmann/Heinz Brüdigam/Barbara Mausbach-Bromberger/Max Oppenheimer, Der deutsche antifaschistische Widerstand 1033-1945 im Bildern und Dokumenten, 4. verb. Aufl. Frankfurt a.M. 1984 Alumni Who Touched Our Lives, in: Alumni Magazine (Madison, Wisconsin), 1996 C. C. Aronsfeld, Opposition und Nonkonformismus. Nach den Quellen der Wiener Library, in: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (Hg.), Stand und Problematik der Erforschung des Widerstandes gegen den Nationalsozialismus, S. 58-83 Klaus Bästlein, Zum Erkenntniswert von Justizakten aus der NS-Zeit. Erfahrungen in der konkreten Forschung, in: Jürgen Weber (Bearb.), Datenschutz und Forschungsfreiheit. Die Archivgesetzgebung des Bundes auf dem Prüfstand, München 1986, S. 85-102 Herbert Bauch u.a. (Bearb.), Quellen zu Widerstand und Verfolgung unter der NS-Diktatur in hessischen Archiven. Übersicht über d8ie Bestände in Archiven und Dokumentationsstellen, Hg. Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden 1995 (Veröffentlichungen der Historischen Kommission für Nassau, Bd. 57) Lothar Bembenek/Axel Ulrich, Widerstand und Verfolgung in Wiesbaden 1933-1945. Eine Dokumentation, Gießen 1990 Olaf Berggötz, Ernst Jünger und die Geiseln. Die Denkschrift von Ernst Jünger über die Geiselerschießungen in Frankreich 1941/42, in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, 51 (2003), S. -

Roeder, Manfred 0015

, FOR OFFICIIAL USE ONLY CE TL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY \-4EPORT NO. a) 44-18 INFORMATION FROM FOREIGN D CUMENTS OR RADIO BROADCASTS CD NO. I S-180 COUNTRY German Feder Republic DATE OF INFORMATION 1952 SUBJECT Political - sistance, espionage HOW DATE DIST. c;.. V E C. 19514 PUBLISHED Book WHERE PUBLISHED Hamburg NO. OF PAGES 31 DATE PUBLISHED 1952 SUPPLEMENT TO LANGUAGE German. REPORT NO. THIS IS UNEVALUATED INFORMATION - ,OURCE Die Rote Ka e Hamburg, 52 pp.7-36 • ••. TicIL RED BAND Dr M. Roeder DECL ASSIFIED AND R ELEASED BY CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY SOURCES METHODS EXEMPT laNaM NAZI WAR CRIMESDISCLOCIURE DATE 2004 2006 PLEASE NOTE THIS IS AN UNEDITED TRANSLATION DISSEMINATED FOR THE IN ORMATION or THE INTELLIGENCE ADVI- SORY COMMIT EE AGENCIES ONLY. IF FURTHER DIS- SEMINATIO S NECESSARY, THIS COVER SHEET MUST BE REMOVED NO CIA MUST NOT BE IDENTIFIED AS THE SOURCE. FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Diotoba-1 TE NAVY NSR8 DISTRIbUTION' iY AIR FBI co 40 18 WARNING Laws relating to copyright, libel, slander and communications require that tbe dissemination of part of thid text be limited to "Official Use Only." Exception can be granted only by the issuing agency . Users are warned that noncompliance may sub- ject violators to personal liability. THE RED BAND Die Rote Kapelle [The ed Band], Judge Advocate Gen. Hamburg, 1952, Pages 7 36 Dr. M. Roeder Civilization and technology have created new possibilities and forms of development in all fie ds of human endeavor. Behind us lies a war whose Li- nal decision is indisp table. How true are Clausewitz theories on war even today. -

Mildred Harnack Und Die Rote Kapelle in Berlin

Ingo Juchler (Hrsg.) Mildred Harnack und die Rote Kapelle in Berlin Mildred Harnack und die Rote Kapelle in Berlin Ingo Juchler (Hrsg.) Mildred Harnack und die Rote Kapelle in Berlin Universitätsverlag Potsdam Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. Universitätsverlag Potsdam 2017 http://verlag.ub.uni-potsdam.de/ Am Neuen Palais 10, 14469 Potsdam Tel.: +49 (0)331 977 2533 / Fax: -2292 E-Mail: [email protected] Satz: text plus form, Dresden Druck: Schaltungsdienst Lange oHG, Berlin | www.sdl-online.de Das Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Umschlagbild: Portrait von Mildred Harnack-Fish als Dozentin in Madison um 1926 | Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand ISBN 978-3-86956-407-4 Zugleich online veröffentlicht auf dem Publikationsserver der Universität Potsdam URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-398166 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-398166 Inhalt Ingo Juchler Einführung: Mildred Harnack – Mittlerin der amerikanischen Literatur und Widerstandskämpferin 7 Ladina Ambauen | Christian Becker | Moritz Habl | Bernhard Keitel | Nikolai Losensky | Patricia Wockenfuß Kapitel 1: Widerstand in Deutschland – ein kurzer Überblick 15 Christian Mrowietz | Imke Ockenga | Lena Christine Jurkatis | Mohamed Chaker Chahrour | Nora Lina Zalitatsch Kapitel 2: Die Rote Kapelle 53 Maren Arnold | Edis Destanovic | Marc Geißler | Sandra Hoffmann | Roswitha Stephan | Christian Weiß Kapitel 3: Mildred Harnack 79 Uwe Grünberg | Dominic Nadol | Tobias Pürschel | Ole Wiecking Kapitel 4: Karl Behrens 109 Alexandra Fretter | Asja Naumann | Anne Pohlandt | Michelle Recktenwald | Christina Weinkamp Kapitel 5: Bodo Schlösinger 123 Ingo Juchler Kapitel 6: Interview mit dem Leiter der Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand in Berlin, Prof. -

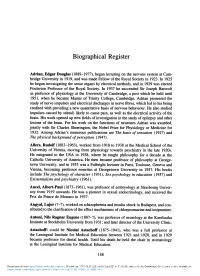

Biographical Register

Biographical Register Adrian, Edgar Douglas (1889-1977), began lecturing on the nervous system at Cam- bridge University in 1919, and was made Fellow of the Royal Society in 1923. In 1925 he began investigating the sense organs by electrical methods, and in 1929 was elected Foulerton Professor of the Royal Society. In 1937 he succeeded Sir Joseph Barcroft as professor of physiology at the University of Cambridge, a post which he held until 1951, when he became Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. Adrian pioneered the study of nerve impulses and electrical discharges in nerve fibres, which led to his being credited with providing a new quantitative basis of nervous behaviour. He also studied impulses caused by stimuli likely to cause pain, as well as the electrical activity of the brain. His work opened up new fields of investigation in the study of epilepsy and other lesions of the brain. For his work on the functions of neurones Adrian was awarded, jointly with Sir Charles Sherrington, the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for 1932. Among Adrian's numerous publications are The basis of sensation (1927) and The physical background ofperception (1947). Aliers, Rudolf (1883-1963), worked from 1918 to 1938 at the Medical School of the University of Vienna, moving from physiology towards psychiatry in the late 1920s. He emigrated to the USA in 1938, where he taught philosophy for a decade at the Catholic University of America. He then became professor of philosophy at George- town University, and in 1955 was a Fulbright lecturer in Paris, Toulouse, Geneva and Vienna, becoming professor emeritus at Georgetown University in 1957. -

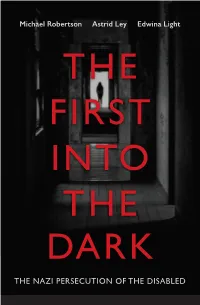

The Fir S T Int O the D

Robertson Robertson Michael Robertson Astrid Ley Edwina Light UNDER THE NAZI REGIME A SECRET PROGRAM OF ‘EUTHANASIA’ WAS Ley UNDERTAKEN AGAINST THE SICK Light AND DISABLED. KNOWN AS THE KRANKENMORDE (THE MURDER OF THE SICK) 300,000 PEOPLE WERE KILLED. A THE INTO THE FIRST THE FURTHER 400,000 WERE STERILISED AGAINST THEIR WILL. MANY COMPLICIT DOCTORS, NURSES, SOLDIERS AND BUREAUCRATS WOULD FIRST THEN PERPETRATE THE HOLOCAUST. _ From eyewitness accounts, records and case fi les, The First into the Dark narrates a history of the victims, perpetrators, opponents to and INTO witnesses of the Krankenmorde, and reveals deeper implications for contemporary society: moral values and ethical challenges in end of life decisions, reproduction and contemporary DARK genetics, disability and human rights, and in THE remembrance and atonement for the past. DARK UTS ePRESS, IS A PEER REVIEWED, OPEN ACCESS THE NAZI PERSECUTION OF THE DISABLED SCHOLARLY PUBLISHER. THE FIRST INTO THE DARK Michael Robertson Astrid Ley Edwina Light THE FIRST INTO THE DARK THE NAZI PERSECUTION OF THE DISABLED UTS ePRESS University of Technology Sydney Broadway NSW 2007 AUSTRALIA epress.lib.uts.edu.au Copyright Information This book is copyright. The work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial-Non Derivatives License CC BY-NC-ND http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 First Published 2019 © 2019 in the text and images, the authors © 2019 in the book design and layout, UTS ePRESS Publication Details DOI citation: https://doi.org/10.5130/aae ISBN: 978-0-6481242-2-1 (paperback) ISBN: 978-0-6481242-3-8 (pdf) ISBN: 978-0-6481242-5-2 (ePub) ISBN: 978-0-6481242-6-9 (Mobi) Peer Review This work was peer reviewed by disciplinary experts. -

Carl Gustav Jung, Avant-Garde Conservative

Carl Gustav Jung, Avant-garde Conservative by Jay Sherry submitted to the Doctoral Committee of the Department of Educational Science and Psychology at the Freie Universität Berlin March 19, 2008 Date of Disputation: March 19, 2008 Referees: 1. Prof. Dr. Christoph Wulf 2. Prof. Dr. Gunter Gebauer Chapters Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Basel Upbringing 5 3. Freud and the War Years 30 4. Jung’s Post-Freudian Network 57 5. His Presidency 86 6. Nazi Germany and Abroad 121 7. World War II Years 151 8. The Cold War Years 168 9. Jung’s Educational Philosophy 194 Declaration of independent work 210 Jay Sherry Resumé 211 Introduction Carl Gustav Jung has always been a popular but never a fashionable thinker. His ground- breaking theories about dream interpretation and psychological types have often been overshadowed by allegations that he was anti-Semitic and a Nazi sympathizer. Most accounts have unfortunately been marred with factual errors and quotes taken out of context; this has been due to the often partisan sympathies of those who have written about him. Some biographies of Jung have taken a “Stations-of-the-Cross” approach to his life that adds little new information. Richard Noll’s The Jung Cult and The Aryan Christ were more specialized studies but created a sensationalistic portrait of Jung based on highly selective and flawed assessment of the historical record. Though not written in reaction to Noll (the research and writing were begun long before his books appeared), this dissertation is intended to offer a comprehensive account of the controversial aspects of Jung’s life and work. -

Libertas Schulze-Boysen * 20

Libertas Schulze-Boysen * 20. November 1913 in Paris; † 22. Dezember 1942 in Berlin-Plötzensee Libertas Schulze Boysen, geb. Haas-Heye http://www.gdw-berlin.de/de/vertiefung/biographien/biografie/view-bio/schulze-boysen-1/ Gästebücher Bd V Tora Haas-Heye mit ihren Kindern Ottora, Johannes und Libertas Aufenthalt Schloss Neubeuern: 4. Juni – 10. Juli 1914 Libertas Schulze-Boysen, geborene Libertas Viktoria Haas-Heye gehörte als Mitwisserin und Helferin während des NS-Regimes zur Widerstandsgruppe Rote Kapelle. Leben Eröffnungseite des Feldurteils des Reichskriegsgerichts vom 19. Dezember 1942 Libertas Schulze-Boysen war das jüngste von drei Kindern des aus Heidelberg stammenden Modeschöpfers Prof. Otto Ludwig Haas-Heye (1879–1959) und dessen Frau Viktoria Ada Astrid Agnes, Fürstin zu Eulenburg und Hertefeld, Gräfin Sandels (1886–1967). Die Eltern hatten am 12. Mai 1909 in Liebenberg geheiratet und danach zeitweise in London und Paris gelebt. Ihre Geschwister waren Ottora Maria (* 13. Februar 1910 in Garmisch-Partenkirchen; † 2001) und Johannes Haas-Heye (1912–2008). Johannes Haas-Heye 2005 in Bonn Gästebücher Bd VI Tora bringt ihren Sohn Johannes als Schüler nach Neubeuern Die Mutter, genannt „Thora“, entstammte einer alten preußischen Adelsfamilie. Sie war das jüngste von acht Kindern des preußischen Diplomaten Philipp zu Eulenburg (1847–1921) und dessen schwedischer Ehefrau, Augusta Gräfin Sandels (1853–1941). Als Libertas acht Jahre alt war, ließen sich die Eltern scheiden. Libertas verbrachte einen Teil ihrer Kindheit auf dem bei Berlin gelegenen Landgut der Eulenburgs, Schloss Liebenberg (heute Löwenberger Land).[1] Fürst Eulenburg und seine Frau Augusta Schloss Liebenberg Fürst Eulenburg (2. V.l.) zu Besuch im Schloss Neubeuern um 1890. -

ROEDER, MANFRED 0013.Pdf

DECLASSIFIED AND RE LEASED BY CENTRkl INTELLIGENCE AGENCY SOUR-ICES METHODS EXEMPT 10qA-y S IICA., r "ea,r) nT NAZI WAR CR INES OISCLOSM DATE 2004 2006 . The Rote Kapelle (FINCK Study) C. ,_] . 1. Harro S HULZE-BOYSEN was born on 2 September 1909 in Kiel to naval officer Edgar SC ZE and his wife, Marie-Louise nee BOYSEN. He grew up in Berlin and Duisb rg. After completing his education, SCHULZE-,BOYSEN became a member of the Jungdeutschen Ordens". He traveled abroad to Sweden and . England, visitin friends and relatives. After his Abitur exams, he began to study law. He n ver finished his law studies because he chose to enter politics. In 19 2 he became a member of the editorial staff of the "Gegner", a political peni dical. Soon he became its chief editor and published his own political br chure, "Gegner von heute, Kampfgenossen von Morgen" (Enemy today; ally tomo row). 2. In Apri 1933 the Nazi regime banned the "Gegner" and its offices were destroyed. Harr SCHULZE-BOYSEN and some of his co-workers were arrested by SS-Sturm troops. The troops were very brutal towards the men they arrested and even maltrea ed one of the prisoners so badly that he died. SCHULZE-BOYSENs mother came to rlin and was successful in getting her sons release. The release was gran ed on the condition that SCHULZE-BOYSEN leave Berlin and in the future, stay out of politics. 3. SCHULZE BOYSEN then took a one-year course at the Verkehrs-Fliegerschule in Warnemuende. -

The Exclusion of Erich Fromm from the IPA Paul Roazen

Publikation der Internationalen Erich-Fromm-Gesellschaft e.V. Publication of the International Erich Fromm Society Copyright © beim Autor / by the author The Exclusion of Erich Fromm from the IPA Paul Roazen “The Exclusion of Erich Fromm from the IPA,“ in: Contemporary Psychoanalysis, New York (Wil- liam Alanson White Psychoanalytic Society), Vol. 37 (2001), pp. 5-42. Copyright © 2001 by Professor Dr. Paul Roazen, 2009 by the Estate of Paul Roazen. The subject of psychoanalytic lineage has re- England published under the title The Fear of cently acquired a new respectability among his- Freedom) became for years a central text in the torians in the field; although privately analysts education of social scientists. Works of Fromm’s have known and acknowledged how critical it is like Man For Himself, Psychoanalysis and Relig- who has gone where and to whom for training, ion, The Forgotten Language, and also The Sane it is only relatively rarely that public attention Society5 formed an essential part of my genera- has been focused on the unusually powerful im- tion’s general education. (Fromm’s most horta- pact which such training analyses can have. The tory last writings, and his specifically political special suggestive role of analytic training ex- ones, fall I think into a different category as far periences was long ago pointed out in the as the general influence that he had; still, the course of controversial in-fighting by such differ- book Fromm co-authored with Michael Mac- ently oriented pioneers as Edward Glover1 and coby, Social Character in a Mexican Village, de- Jacques Lacan, but it has been unusual to find serves more attention.6 Fromm’s The Art of Lov- the institution of training analysis itself publicly ing has meanwhile sold millions of copies, and challenged.