Democracy, Threat, and Repression: Kidnapping and Repressive Dynamics During the Colombian Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elections in Colombia: 2014 Presidential Elections

Elections in Colombia: 2014 Presidential Elections Frequently Asked Questions Latin America and the Caribbean International Foundation for Electoral Systems 1850 K Street, NW | Fifth Floor | Washington, D.C. 20006 | www.IFES.org May 23, 2014 Frequently Asked Questions When is Election Day? ................................................................................................................................... 1 Who are citizens voting for on Election Day? ............................................................................................... 1 Who is eligible to vote?................................................................................................................................. 1 How many candidates are registered for the May 25 elections? ................................................................. 1 Who are the candidates running for President?........................................................................................... 1 How many registered voters are there? ....................................................................................................... 3 What is the structure of the government? ................................................................................................... 3 What is the gender balance within the candidate list? ................................................................................ 3 What is the election management body? What are its powers? ................................................................. 3 How many polling -

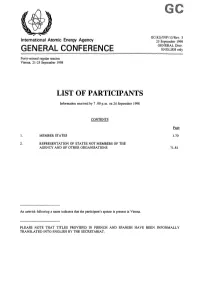

List of Participants

International Atomic Energy Agency GC(42)/INF/13/Rev.1 22 September 1998 GENERAL Distr. GENERAL CONFERENCE ENGLISH only Forty-second regular session Vienna, 21-25 September 1998 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Information received by 7 .00 p.m. on 21 September 1998 CONTENTS Page 1. MEMBER STATES 1-70 2. REPRESENTATION OF STATES NOT MEMBERS OF THE AGENCY AND OF OTHER ORGANISATIONS 71-80 An asterisk following a name indicates that the participant's spouse is present in Vienna. PLEASE NOTE THAT TITLES PROVIDED IN FRENCH AND SPANISH HAVE BEEN INFORMALLY TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH BY THE SECRETARIAT. REQUESTS FOR CHANGES IN SUBSEQUENT EDITIONS OF THIS LIST SHOULD BE MADE TO THE PROTOCOL OFFICE IN WRITING. 1. MEMBER STATES AFGHANISTAN Delegate: Mr. Farid A. AMIN Acting Resident Representative to the Agency ALBANIA Delegate: Mr. Spiro KOÇI First Secretary Alternate to the Resident Representative Alternate: Mr. Robert KUSHE Director Institute of Nuclear Physics, Tirana ALGERIA Delegate: Mr. Abderrahmane KADRI Atomic Energy Commission Head of the Delegation Advisers: Mr. Mokhtar REGUIEG Ambassador to Austria Resident Representative to the Agency Mr. El Arbi ALIOUA Counsellor Atomic Energy Commission Mr. Mohamed CHIKOUCHE Counsellor Atomic Energy Commission Mr. Salah DJEFFAL Director Center for Radiation Protection and Security (CRS) Mr. YoussefTOUIL Director Center for Development of Nuclear Technologies (CDTN) Mr. Ali AISSAOUI Counsellor Atomic Energy Commission Mr. Abdelmadjid DRAIA Counsellor Permanent Mission in Vienna Mr. Boualem CHEBIHI Counsellor, Ministry of Foreign Affairs ARGENTINA Delegate: Mr. Juan Carlos KRECKLER Ambassador Alternates: Mr. Dan BENINSON President of the Board Nuclear Regulatory Authority (ARN) Alternate to the Governor Mr. Pedro VILLAGRA DELGADO Director, International Security Ministry of Foreign Affairs, International Trade and Worship Alternate to the Governor Mr. -

The Venezuelan Crisis, Regional Dynamics and the Colombian Peace Process by David Smilde and Dimitris Pantoulas Executive Summary

Report August 2016 The Venezuelan crisis, regional dynamics and the Colombian peace process By David Smilde and Dimitris Pantoulas Executive summary Venezuela has entered a crisis of governance that will last for at least another two years. An unsustainable economic model has caused triple-digit inflation, economic contraction, and widespread scarcities of food and medicines. An unpopular government is trying to keep power through increasingly authoritarian measures: restricting the powers of the opposition-controlled National Assembly, avoiding a recall referendum, and restricting civil and political rights. Venezuela’s prestige and influence in the region have clearly suffered. Nevertheless, the general contours of the region’s emphasis on regional autonomy and state sovereignty are intact and suggestions that Venezuela is isolated are premature. Venezuela’s participation in the Colombian peace process since 2012 has allowed it to project an image of a responsible member of the international community and thereby counteract perceptions of it as a “rogue state”. Its growing democratic deficits make this projected image all the more valuable and Venezuela will likely continue with a constructive role both in consolidating peace with the FARC-EP and facilitating negotiations between the Colombian government and the ELN. However, a political breakdown or humanitarian crisis could alter relations with Colombia and change Venezuela’s role in a number of ways. Introduction aimed to maximise profits from the country’s oil production. During his 14 years in office Venezuelan president Hugo Together with Iran and Russia, the Venezuelan government Chávez Frias sought to turn his country into a leading has sought to accomplish this through restricting produc- promotor of the integration of Latin American states and tion and thus maintaining prices. -

Yearbook Peace Processes.Pdf

School for a Culture of Peace 2010 Yearbook of Peace Processes Vicenç Fisas Icaria editorial 1 Publication: Icaria editorial / Escola de Cultura de Pau, UAB Printing: Romanyà Valls, SA Design: Lucas J. Wainer ISBN: Legal registry: This yearbook was written by Vicenç Fisas, Director of the UAB’s School for a Culture of Peace, in conjunction with several members of the School’s research team, including Patricia García, Josep María Royo, Núria Tomás, Jordi Urgell, Ana Villellas and María Villellas. Vicenç Fisas also holds the UNESCO Chair in Peace and Human Rights at the UAB. He holds a doctorate in Peace Studies from the University of Bradford, won the National Human Rights Award in 1988, and is the author of over thirty books on conflicts, disarmament and research into peace. Some of the works published are "Procesos de paz y negociación en conflictos armados” (“Peace Processes and Negotiation in Armed Conflicts”), “La paz es posible” (“Peace is Possible”) and “Cultura de paz y gestión de conflictos” (“Peace Culture and Conflict Management”). 2 CONTENTS Introduction: Definitions and typologies 5 Main Conclusions of the year 7 Peace processes in 2009 9 Main reasons for crises in the year’s negotiations 11 The peace temperature in 2009 12 Conflicts and peace processes in recent years 13 Common phases in negotiation processes 15 Special topic: Peace processes and the Human Development Index 16 Analyses by countries 21 Africa a) South and West Africa Mali (Tuaregs) 23 Niger (MNJ) 27 Nigeria (Niger Delta) 32 b) Horn of Africa Ethiopia-Eritrea 37 Ethiopia (Ogaden and Oromiya) 42 Somalia 46 Sudan (Darfur) 54 c) Great Lakes and Central Africa Burundi (FNL) 62 Chad 67 R. -

Assessing the US Role in the Colombian Peace Process

An Uncertain Peace: Assessing the U.S. Role in the Colombian Peace Process Global Policy Practicum — Colombia | Fall 2018 Authors Alexandra Curnin Mark Daniels Ashley DuPuis Michael Everett Alexa Green William Johnson Io Jones Maxwell Kanefield Bill Kosmidis Erica Ng Christina Reagan Emily Schneider Gaby Sommer Professor Charles Junius Wheelan Teaching Assistant Lucy Tantum 2 Table of Contents Important Abbreviations 3 Introduction 5 History of Colombia 7 Colombia’s Geography 11 2016 Peace Agreement 14 Colombia’s Political Landscape 21 U.S. Interests in Colombia and Structure of Recommendations 30 Recommendations | Summary Table 34 Principal Areas for Peacebuilding Rural Development | Land Reform 38 Rural Development | Infrastructure Development 45 Rural Development | Security 53 Rural Development | Political and Civic Participation 57 Rural Development | PDETs 64 Combating the Drug Trade 69 Disarmament and Socioeconomic Reintegration of the FARC 89 Political Reintegration of the FARC 95 Justice and Human Rights 102 Conclusion 115 Works Cited 116 3 Important Abbreviations ADAM: Areas de DeBartolo Alternative Municipal AFP: Alliance For Progress ARN: Agencies para la Reincorporación y la Normalización AUC: Las Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia CSDI: Colombia Strategic Development Initiative DEA: Drug Enforcement Administration ELN: Ejército de Liberación Nacional EPA: Environmental Protection Agency ETCR: Espacio Territoriales de Capacitación y Reincorporación FARC-EP: Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia-Ejército del Pueblo GDP: Gross -

Targeting Civilians in Colombia's Internal Armed

‘ L E A V E U S I N P E A C E ’ T LEAVE US IN A ‘ R G E T I N G C I V I L I A N S PEA CE’ I N C O TARG ETING CIVILIANS L O M B I A IN COL OM BIA S INTERNAL ’ S ’ I N T E R ARMED CONFL IC T N A L A R M E D C O N F L I C ‘LEAVE US IN PEACE’ T TARGETING CIVILIANS IN COLOMBIA ’S INTERNAL ARMED CONFLICT “Leave us in peace!” – Targeting civilians in Colombia’s internal armed conflict describes how the lives of millions of Colombians continue to be devastated by a conflict which has now lasted for more than 40 years. It also shows that the government’s claim that the country is marching resolutely towards peace does not reflect the reality of continued A M violence for many Colombians. N E S T Y At the heart of this report are the stories of Indigenous communities I N T decimated by the conflict, of Afro-descendant families expelled from E R their homes, of women raped and of children blown apart by landmines. N A The report also bears witness to the determination and resilience of T I O communities defending their right not to be drawn into the conflict. N A L A blueprint for finding a lasting solution to the crisis in Colombia was put forward by the UN more than 10 years ago. However, the UN’s recommendations have persistently been ignored both by successive Colombian governments and by guerrilla groups. -

S/PV.8581 Colombia 19/07/2019

United Nations S/ PV.8581 Security Council Provisional Seventy-fourth year 8581st meeting Friday, 19 July 2018, 10.20 a.m. New York President: Mr. Popolizio Bardales ........................... (Peru) Members: Belgium ....................................... Mr. Pecsteen de Buytswerve China ......................................... Mr. Wu Haitao Côte d’Ivoire ................................... Mr. Ipo Dominican Republic .............................. Mr. Singer Weisinger Equatorial Guinea ............................... Mr. Ndong Mba France ........................................ Mr. De Rivière Germany ...................................... Mr. Heusgen Indonesia. Mr. Djani Kuwait ........................................ Mr. Alotaibi Poland ........................................ Ms. Wronecka Russian Federation ............................... Mr. Nebenzia South Africa ................................... Mr. Matjila United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .. Mr. Allen United States of America .......................... Mr. Hunter Agenda Identical letters dated 19 January 2016 from the Permanent Representative of Colombia to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council (5/2016/53) Report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia (S/2019/530) This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages only. They should be incorporated in a copy of the record and sent under the signature of a member of the delegation concerned to the Chief of the Verbatim Reporting Service, room U-0506 ([email protected]). Corrected records will be reissued electronically on the Official Document System of the United Nations (http://documents.un.org). 19-22372 (E) *1922372* S/PV.8581 Colombia 19/07/2019 The meeting was called to order at 10.20 a.m. -

Human Security Policies in the Colombian Conflict During the Uribe Government

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 3>6,7 <0.>;4=@ 9854.40< 47 =30 .8586-4,7 .87154.= />;472 =30 >;4-0 28?0;7607= /INGN 6NMREIPN /APIN , =HEQIQ <SBLIRRED FNP RHE /EGPEE NF 9H/ AR RHE >MITEPQIRV NF <R ,MDPEUQ &$%' 1SKK LERADARA FNP RHIQ IREL IQ ATAIKABKE IM <R ,MDPEUQ ;EQEAPCH ;EONQIRNPV AR+ HRRO+##PEQEAPCH!PEONQIRNPV"QR!AMDPEUQ"AC"SJ# 9KEAQE SQE RHIQ IDEMRIFIEP RN CIRE NP KIMJ RN RHIQ IREL+ HRRO+##HDK"HAMDKE"MER#%$$&'#()%* =HIQ IREL IQ OPNRECRED BV NPIGIMAK CNOVPIGHR =HIQ IREL IQ KICEMQED SMDEP A .PEARITE .NLLNMQ 5ICEMCE Human security policies in the Colombian conflict during the Uribe government Diogo Monteiro Dario This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 17 May 2013 Diogo Monteiro Dario PhD Dissertation Human security policies in the Colombian conflict during the Uribe government 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Diogo Monteiro Dario, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 72,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September, 2009 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in May, 2010; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2010 and 2013. Date 14 th May 2013 signature of candidate ……… 2. -

List of Participants

GC(42)/INF/13/Rev. 3 International Atomic Energy Agency 25 September 1998 GENERAL Distr. GENERAL CONFERENCE ENGLISH only Forty-second regular session Vienna, 21-25 September 1998 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Information received by 7 .00 p.m. on 24 September 1998 CONTENTS 1. MEMBER STATES 1-70 2. REPRESENTATION OF STATES NOT MEMBERS OF THE AGENCY AND OF OTHER ORGANISATIONS 71-81 An asterisk following a name indicates that the participant's spouse is present in Vienna. PLEASE NOTE THAT TITLES PROVIDED IN FRENCH AND SPANISH HAVE BEEN INFORMALLY TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH BY THE SECRETARIAT. 1. MEMBER STATES AFGHANISTAN Delegate: Mr. Farid A. AMIN Acting Resident Representative to the Agency ALBANIA Delegate: Mr. Spiro KOÇI First Secretary Alternate to the Resident Representative Alternate: Mr. Robert KUSHE Director Institute of Nuclear Physics, Tirana ALGERIA Delegate: Mr. Abderrahmane KADRİ Chairman, Atomic Energy Commission Head of the Delegation Advisers: Mr. Mokhtar REGUIEG Ambassador to Austria Resident Representative to the Agency Mr. El Arbi ALIOUA Counsellor Atomic Energy Commission Mr. Mohamed CHIKOUCHE Counsellor Atomic Energy Commission Mr. Salah DJEFFAL Director Center for Radiation Protection and Security (CRS) Mr. YoussefTOUIL Director Center for Development of Nuclear Technologies (CDTN) Mr. Ali AISSAOUI Counsellor Atomic Energy Commission Mr. Abdelmadjid DRAIA Counsellor Permanent Mission in Vienna Mr. Boualem CHEBIHI Counsellor, Ministry of Foreign Affairs ARGENTINA Delegate: Mr. Juan Carlos KRECKLER Ambassador to Austria Designated Resident Representative to the Agency Alternates: Mr. Dan BENINSON President of the Board Nuclear Regulatory Authority (ARN) Alternate to the Governor Mr. Pedro VILLAGRA DELGADO Director, International Security Ministry of Foreign Affairs, International Trade and Worship Alternate to the Governor Mr. -

Boletín 53.Indd

Unidad de análisis • www.ideaspaz.org/publicaciones • página 1 Siguiendo el conflicto: hechos y análisis de la semana Número 53/ 1 de abril de 2008 The Sources of Chávez’s Conduct is this to Colombian-Venezuelan relations? Both Roman D. Ortiz* questions are of critical importance. Since Hugo Area Coordinator, Security and Defense Studies Chávez took the reins of government, Venezuela’s strategic importance for Colombian affairs has George Kennan’s classic work on US strategy vis- grown in every conceivable form. The volume of à-vis the Soviet Union, “The Sources of Soviet trade between the two countries has skyrocketed, Conduct”, recently marked its 60th anniversary.1 The with Caracas receiving close to 15 percent of text, which served as the theoretical underpinning Bogotá’s exports, totaling over $5.2 billion in for the West’s containment policy for decades to 2007. Likewise, President Chávez’s visibility within come, is a clear example of a successful attempt to the Colombian political arena has also increased, overcome the strategic bewilderment of American insofar as his Bolivarian discourse of Latin diplomatic thought when confronted with an American integration accords a central place to the ascending power that pursued unconventional political association of Bogota and Caracas. Above foreign policy objectives with unorthodox methods. all, however, the Venezuelan head of state was Thus, much of the Kennan’s merit lies in his ability catapulted into a leading role on the Colombian to propose a new line of thinking and a new course domestic political scene in September 2007, when of action in response to an emerging international the Uribe administration authorized him to serve as actor that required a novel political response. -

Anuario Accion Human 2012.Indd

ISSN: 1885-298X Anuario de Acción Humanitaria y Derechos Humanos Yearbook on Humanitarian Action and Human Rights 2012 Deusto Universidad de Deusto University of Deusto Anuario de Acción Humanitaria y Derechos Humanos Yearbook on Humanitarian Action and Human Rights 2012 Universidad de Deusto - Instituto de Derechos Humanos Pedro Arrupe University of Deusto - Pedro Arrupe Institute of Human Rights 2012 Instituto de Derechos Humanos Pedro Arrupe: Avda. de las Universidades, 24 48007 Bilbao Teléfono: 94 413 91 02 Fax: 94 413 92 82 Correo electrónico para envíos de artículos: [email protected] URL: http://www.idh.deusto.es Coordinación editorial: Gorka Urrutia, Instituto de Derechos Humanos Pedro Arrupe Consejo de Redacción: Joana Abrisketa, Instituto de Derechos Humanos Pedro Arrupe Cristina Churruca, Instituto de Derechos Humanos Pedro Arrupe Eduardo J. Ruiz Vieytez, Instituto de Derechos Humanos Pedro Arrupe Gorka Urrutia, Instituto de Derechos Humanos Pedro Arrupe Consejo Asesor: Susana Ardanaz, Instituto de Derechos Humanos Pedro Arrupe Carlos Camacho Nassar, DANIDA Francisco Ferrándiz, Centro Superior de Investigaciones Científi cas Koen de Feyter, University of Antwerp Xabier Etxeberria, Universidad de Deusto Javier Hernandez, United Nations-Offi ce of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Mbuyi Kabunda, University of Basel Asier Martínez de Bringas, Universidad de Deusto Fernando Martínez Mercado, Universidad de Chile Guillermo Padilla Rubiano, University of Texas Felipe Gómez, Instituto de Derechos Humanos Pedro Arrupe Francisco Rey, IECAH-Instituto de Estudios sobre Confl ictos y Acción Humanitaria Nancy Robinson, United Nations-Offi ce of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Trinidad L. Vicente, Instituto de Derechos Humanos Pedro Arrupe Marta Zubia, Instituto de Derechos Humanos Pedro Arrupe Cualquier forma de reproducción, distribución, comunicación pública o transformación de esta obra sólo puede ser realizada con la autorización de sus titulares, salvo excepción prevista por la ley. -

Journal Unit (E-Mail [email protected]; Tel

No. 2019/140 Saturday, 20 July 2019 Journal of the United Nations Programme of meetings and agenda Monday, 22 July 2019 Official meetings For changes to the venue or time of meetings of today, please consult the digital Journal at https://journal.un.org/ Launch of the digital Journal of the United Nations In accordance with General Assembly resolution 71/323, a digital version of the Journal of the United Nations is available at https://journal.un.org. This multilingual user-friendly website is also compatible with smart phones and tablets. Pursuant to the same resolution, all content related to official meetings, including summaries, is available in the six official languages, in compliance with rule 55 of the rules of procedure of the General Assembly, while other meetings and general information will continue to be published in English and French only. General Assembly Security Council Seventy-third session 10:00 Consultations of Security Council 15:00 Informal consultations Conference the whole (closed) Consultations (closed) Room 3 Room 1701 report - S/2019/574 On the political declaration of the high-level Other matters meeting on universal health coverage (continued on page 2) Take advantage of the e-subscription and receive the Journal early morning! www.undocs.org Join us and be the first to be notified once the next issue is available! www.twitter.com/Journal_UN_ONU Look for our page! Journal of the United Nations Scan QR Code (Quick Response Code) at the top right corner to download today’s Journal. 19-10593E 19-10593E Think Green! Please recycle No. 2019/140 Journal of the United Nations Saturday, 20 July 2019 15:00 Consultations of Security Council the whole (closed) Consultations Room MINUJUSTH - S/2019/563 Other matters Communications addressed to the President of the Security Council should be delivered to the Office of the President of the Security Council or emailed to the secretariat of the Council.