Transcript of Oral History Recording

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

1 Below Is a Comprehensive List of All the Lines Hello Barbie Says As O

Below is a comprehensive list of all the lines Hello Barbie says as of November 17, 2015. We are consistently updating and enhancing the product’s vocabulary and will update the lines on this site periodically to reflect any changes. OK, sooooo..... I love hanging out with you! (SIGH) Wow... there's so much we can talk about... I've got a question for you... Oh! I know what we can talk about... Oh, I know what we can do now... Speaking of things you want to be when you grow up... You know what I want to talk about? FRIENDS! So, let's talk friends! Ooh, why don't we talk about friends! Hey... let's talk about friends for a bit! I'm the most myself when I'm around my friends, just playing games and imagining what we'll be when we grow up! You know, I really appreciate my friends who have a completely unique sense of style... like you! You know, on those days where waking up for school is hard, I just think about how much fun it'll be to see my friends. ©2015 Mattel. All Rights Reserved. Version 2 1 You know, talking about all the fun things we do is making me think about who we could do them with ... friends! So we've been talking about family, let's talk about the other people in our lives that mean a lot to us ...like our friends! I bet someone who's a friend to animals knows a thing or two about being a friend to people. -

The Revels Repertoire

THE REVELS REPERTOIRE POP Ain’t It Fun – Paramore Don’t StoP the Music – Rihanna All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor Dynamite – Taio Cruz American Boy – Estelle Everybody – Backstreet Boys Animal – Neon Trees Everybody Talks – Neon Trees Baby I Love Your Way – Big Mountain, Tom Exs and Ohs – Elle King Lord-Alge Firework – Katy Perry Back to Black – Amy Winehouse Forever – Chris Brown Bad Guy – Billie Eilish Forget You – CeeLo Green Bad Romance – Lady Gaga Feels – Calvin Harris, Pharrell Williams, Bang Bang – Jessie J, Ariana Grande, Nicki Katy Perry Minaj Feel It Coming – The Weeknd Believe – Cher Feel It Still – Portugal. The Man Best Day of My Life – American Authors Get Lucky – Daft Punk Born This Way – Lady Gaga Get the Party Started – P!nk Bye Bye Bye – *NSYNC Give Me Everything – Ne-yo and Pitbull Cake by the Ocean – DNCE Good as Hell – Lizzo California Gurls – Katy Perry HaPPy – Pharrel Call Me Maybe – Carly Rae JePsen Havana – Camila Cabello Can’t Hold Us – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Heaven – Los Lonely Boys Can’t StoP the Feeling – Justin Timberlake Hey Soul Sister – Train Candyman – Christina Aguilera High Horse – Kacey Musgraves Chandelier – Sia Ho Hey – The Lumineers CheaP Thrills – Sia Hold My Hand – Jess Glynne Cheerleader – OMI Holiday – Madonna Closer – The Chainsmokers I Don’t Like It, I Love It – Flo Rida and Robin Counting Stars – OneRePublic Thicke Crazy – Gnarls Barkley I Kissed a Girl – Katy Perry CreeP – TLC I Love It – Icona PoP Cruel Summer – Bananarama I Love You Always Forever – Donna Lewis Dancing on My Own – Robyn Into You – Ariana Grande Dear Future Husband – Meghan Trainor I Will Wait – Mumford & Sons Déjà Vu – Beyonce Ice Ice Baby – Vanilla Ice Domino – Jessie J Juice – Lizzo 1 Just Dance – Lady Gaga ShaPe of You – Ed Sheeran Just Fine – Mary J. -

Bat out of Hell 2100 by Jim Steinman an Extended Treatment

BAT OUT OF HELL 2100 BY JIM STEINMAN AN EXTENDED TREATMENT “BAT OUT OF HELL 2100” TITLE CARDS: THE YEAR 2100 SOMEWHERE IN WHAT USED TO BE THE ISLAND OF MANHATTAN BUT WHICH SOMEHOW CHANGED... into something else... PROLOGUE: (No music at all) FADE IN: INT: A MYSTERIOUS BEDROOM (What seems to have once been a perfect bedroom for a fairy tale princess. Whites and pinks and lavenders, flowing satins and silks. Huge windows, lush layered curtains and drapes. A massive canopied bed. But now there is a pervading sense of gradual decay and encroaching ruin. Shadows loom, dust whirls, and intricate webs insinuate themselves into the patterns of the walls and floor corners. Fabrics are torn. Wood is cracked. Glass is chipped. Things are lost. It doesn’t really seem to be a room where anybody lives-- it has the slightly unreal, frozen quality of a museum exhibit that has recently been left a bit too unattended... After moving through the room we come to a woman standing close to one of the largest open windows -- There are sepulchral clouds over the moon and in the slats of light that filter through it is impossible to see her very clearly. She stands totally still, as she brushes her long golden hair, some of which hangs out over the window ledge. She looks up and out and we do too, taking in the hazy outlines of a strange city skyline -- it seems both somewhat futurist and medieval, though so much is obscured by spirals of thick multi-colored smoke and plumes of what seems to be glittering black and gold ash. -

Oabc Radio Networks

WITH SHADOE STEVENS PLEASE AUDITION EACH DISC IMMEDIATELY. IF YOU HAVE ANY QUESTIONS, PLEASE CONTACT US AT (213) 882-8330 . TOPICAL PROMOS TOPICAL PROMOS FOR SHOW #43 ARE LOCATED ON DISC 4, TRACKS 6 1 7 & 8. DO NOT USE AFTER SHOW #43. AT40 ACTUALITIES ARE LOCATED ON DISC 4. TRACKS 9 & JO, IMMEDIATELY FOLLOWING TOPICAL PROMOS 1. K,C. ON K.W.S • .,. MADONNA MAKES HISTORY :35 Hi, I'm Shadoe Stevens. Last week's edition of American Top 40 was filled with all sortsa' music facts and hit history. We had the story behind Shakespear's Sister's hit song and video. We found out about a contest looking for the world's worst guitarist. We talked with the 'Shake Your Booty' man, K.C., from the Sunshine Band, about the K.W.S. remake of his hit, "Please Don't Go". We had the highest debut in AT40 history, comin' in at #2!! With her new song, "Erotica", Madonna!! And Boyz II Men spent their 9th week at #1 for one of the biggest hits in more than a decade. What's gonna happen this week? Only one way to find out, count 'em down with me, right here, on American Top 40. {LOCAL TAG) 2. BOVZ ARE BIG BUT CAN THEY 'ROADBLOCK' MADONNA? :30 Hi, I'm Shadoe Stevens with a quick countdown update. Last week on AT40 Boyz II Men spent their ninth incredible week on top of the Billboard chart with radio's #1 hit, "End Of The Road". It's the biggest #1 in more than a decade. -

& His Hbcu Experience

HBCU ConneCt.Com ConferenCe for HBCU AlUmni WINTER 2010 & his hBCU ExpEriEnCE With us, information is not just power. It’s the power behind a brighter future. At The McGraw-Hill Companies, we provide the essential information and insight that helps markets, societies, and individuals maximize their potential. And we can do the same for you. Whether joining us post-graduation, as a new hire, or taking your career to the next level, you’ll quickly fi nd this is an experience like no other. From partnering with managers on critical initiatives, to contributing to high performance teams, you will gain key industry insight and exposure in an environment rich in continuous learning and skills development. If you’re interested in shaping your own future, discover the power to make it happen here, with us. To learn more about our exciting opportunities, visit www.mcgraw-hill.com/careers. We are an equal opportunity employer. 5146247 1 10/19/09 11:48:53 AM TABLE OF CONTENTS P. 6 EatUrEs F 6. HBCU CONNECT 10 YEAR ANNIVERSARY n thE CovEr P. 10 SOean Comb’s HOWARD 10. SEAN Comb’s HOWARD UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY EXPERIENCE AND EXPERIENCE AND THE ULTIMATE THE ULTIMATE BUSINESS MAN BUSINESS MAN 17. BLACK MEN AND DEPRESSION 20. 2010 HBCU ALUMNI WEEKEND CONFERENCE & EXHIBITION EpartmEnts DLETTER FROM THE EDITOR 5. 13. UPCOMING EVENTS 15. ON BLAST: THE GOOD, THE BAD, THE UGLY 16. STAFF EDITORIAL: WHAT ABOUT YOUR FRIENDS? 18. STAFF EDITORIAL: 2009 IN REVIEW 22. GIVING FOR A NEW GENERATION OF ALUMNI P. 20 2010 HBCU ALUMNI WEEKEND CONFERENCE & EXHIBITION advErtisEr inqUiriEs Please contact our sales department at 614.864.4446 or [email protected] join us online: www.hbcuconnect.com • 3 Redefine your edge. -

234 MOTION for Permanent Injunction.. Document Filed by Capitol

Arista Records LLC et al v. Lime Wire LLC et al Doc. 237 Att. 12 EXHIBIT 12 Dockets.Justia.com CRAVATH, SWAINE & MOORE LLP WORLDWIDE PLAZA ROBERT O. JOFFE JAMES C. VARDELL, ID WILLIAM J. WHELAN, ffl DAVIDS. FINKELSTEIN ALLEN FIN KELSON ROBERT H. BARON 825 EIGHTH AVENUE SCOTT A. BARSHAY DAVID GREENWALD RONALD S. ROLFE KEVIN J. GREHAN PHILIP J. BOECKMAN RACHEL G. SKAIST1S PAULC. SAUNOERS STEPHEN S. MADSEN NEW YORK, NY IOOI9-7475 ROGER G. BROOKS PAUL H. ZUMBRO DOUGLAS D. BROADWATER C. ALLEN PARKER WILLIAM V. FOGG JOEL F. HEROLD ALAN C. STEPHENSON MARC S. ROSENBERG TELEPHONE: (212)474-1000 FAIZA J. SAEED ERIC W. HILFERS MAX R. SHULMAN SUSAN WEBSTER FACSIMILE: (212)474-3700 RICHARD J. STARK GEORGE F. SCHOEN STUART W. GOLD TIMOTHY G. MASSAD THOMAS E. DUNN ERIK R. TAVZEL JOHN E. BEERBOWER DAVID MERCADO JULIE SPELLMAN SWEET CRAIG F. ARCELLA TEENA-ANN V, SANKOORIKAL EVAN R. CHESLER ROWAN D. WILSON CITYPOINT RONALD CAM I MICHAEL L. SCHLER PETER T. BARBUR ONE ROPEMAKER STREET MARK I. GREENE ANDREW R. THOMPSON RICHARD LEVIN SANDRA C. GOLDSTEIN LONDON EC2Y 9HR SARKIS JEBEJtAN DAMIEN R. ZOUBEK KRIS F. HEINZELMAN PAUL MICHALSKI JAMES C, WOOLERY LAUREN ANGELILLI TELEPHONE: 44-20-7453-1000 TATIANA LAPUSHCHIK B. ROBBINS Kl ESS LING THOMAS G. RAFFERTY FACSIMILE: 44-20-7860-1 IBO DAVID R. MARRIOTT ROGER D. TURNER MICHAELS. GOLDMAN MICHAEL A. PASKIN ERIC L. SCHIELE PHILIP A. GELSTON RICHARD HALL ANDREW J. PITTS RORYO. MILLSON ELIZABETH L. GRAYER WRITER'S DIRECT DIAL NUMBER MICHAEL T. REYNOLDS FRANCIS P. BARRON JULIE A. -

DJ Song List by Song

A Case of You Joni Mitchell A Country Boy Can Survive Hank Williams, Jr. A Dios le Pido Juanes A Little Bit Me, a Little Bit You The Monkees A Little Party Never Killed Nobody (All We Got) Fergie, Q-Tip & GoonRock A Love Bizarre Sheila E. A Picture of Me (Without You) George Jones A Taste of Honey Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass A Ti Lo Que Te Duele La Senorita Dayana A Walk In the Forest Brian Crain A*s Like That Eminem A.M. Radio Everclear Aaron's Party (Come Get It) Aaron Carter ABC Jackson 5 Abilene George Hamilton IV About A Girl Nirvana About Last Night Vitamin C About Us Brook Hogan Abracadabra Steve Miller Band Abracadabra Sugar Ray Abraham, Martin and John Dillon Abriendo Caminos Diego Torres Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Nine Days Absolutely Not Deborah Cox Absynthe The Gits Accept My Sacrifice Suicidal Tendencies Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Ace In The Hole George Strait Ace Of Hearts Alan Jackson Achilles Last Stand Led Zeppelin Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Across The Lines Tracy Chapman Across the Universe The Beatles Across the Universe Fiona Apple Action [12" Version] Orange Krush Adams Family Theme The Hit Crew Adam's Song Blink-182 Add It Up Violent Femmes Addicted Ace Young Addicted Kelly Clarkson Addicted Saving Abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted Sisqó Addicted (Sultan & Ned Shepard Remix) [feat. Hadley] Serge Devant Addicted To Love Robert Palmer Addicted To You Avicii Adhesive Stone Temple Pilots Adia Sarah McLachlan Adíos Muchachos New 101 Strings Orchestra Adore Prince Adore You Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel -

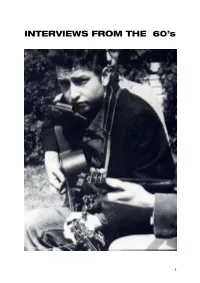

INTERVIEWS from the 60’S

INTERVIEWS FROM THE 60’s 1 INTERVIEWS FROM THE 60’S p4. THE BILLY JAMES INTERVIEW, FALL 1961 p7. FROM THE IZZY YOUNG JOURNALS, OCTOBER 20 1961 p8. THE 'SCENE' INTERVIEW, JANUARY 1963 p11. THE SIDNEY FIELDS INTERVIEW, AUGUST 1963 p13. THE LES CRANE SHOW, FEBRUARY 17 1965 p28. DYLAN MEETS THE PRESS - VILLAGE VOICE, MARCH 3 1965 p30. SHEFFIELD UNIVERSITY PAPER, MAY 1965 p34. THE LAURIE HENSHAW INTERVIEW, MAY 12 1965 p38. BY NORA EPHRON & SUSAN EDMISTON, SUMMER 1965 p46. THE PAUL J. ROBBINS INTERVIEW, MARCH 1965 p56. BOB DYLAN TALKING BY JOSEPH HASS, NOVEMBER 27 1965 p62. PLAYBOY INTERVIEW: BOB DYLAN, FEBRUARY 1966. p82. THE MAURA DAVIS INTERVIEW, FEBRUARY 1966 p87. THE AGE (MELBOURNE), APRILl 19 1966 p89. THE KLAS BURLING INTERVIEW, APRIL 29 1966. p96. COPENHAGEN PRESS CONFERENCE, MAY 1, 1966 p97. LONDON PRESS CONFERENCE, MAY 3 1966 p100. THE AUSTIN INTERVIEW, SEPTEMBER 22 1966 AUSTIN, TEXAS p105. THE ISLE OF WIGHT PRESS CONFERENCE , AUGUST 27, 1969 Source: http://www.interferenza.com/bcs/interv.htm 2 3 THE BILLY JAMES INTERVIEW FALL 1961 This interview was conducted by Billy James of CBS sometime in the Fall, 1961. It is the first known taped interview and this is a transcript of the, unfortunately incomplete tape, published in Stephen Pickering's Praxis: One. A complete transcript (?) was published in New Musical Express 4/24/76. Dylan: Yeah, well I was in the carnival when I was about thirteen - - all kinds of shows. James: Where'd you go? Dylan: All around the mid-west, uh, Gallup, New Mexico, Aptos, Texas, and then .. -

Karaoke Song List

Pirate Radio Productions Songs by Artist Booking: 701-799-5672 Title Title Title 10 Years Aaliyah Adam Sandler Beautiful Try Again Chanukah Song, The 10cc Aaron Lewis Adamski Dreadlock Holiday Country Boy Killer I'm Not In Love Aaron Neville Adele 3 Doors Down Everybody Plays The Fool Chasing Pavements Away From The Sun Tell It Like It Is Make You Feel My Love Be Like That Aaron Tippin Rolling In The Deep Citizen Soldier If Her Lovin' Don't Kill Me Rumour Has It Duck And Run It's Way Too Close To Christmas To Be Set Fire To The Rain Here By Me This Far From You Skyfall Here Without You Kiss This Someone Like You It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) Ready To Rock Turning Tables Kryptonite There Ain't Nothin' Wrong With The Aerosmith Let Me Be Myself Radio Dream On Let Me Go What This Country Needs I Don't Want To Miss A Thing Live For Today Where The Stars And Stripes And The Walk This Way Eagle Fly When I'm Gone Afrojack Feat Wrabel Workin' Man's PH.D When You're Young Ten Feet Tall You've Got To Stand For Something 38 Special Afroman Aaron Tippin (W Thea Tippin) Back Where You Belong Because I Got High Love Like There's No Tomorrow Hold On Loosely A-Ha Abba If I'd Been The One Take On Me Dancing Queen Rockin' Into The Night Air Supply Does Your Mother Know Second Chance All Out Of Love Fernando 3LW Even The Nights Are Better Knowing Me Knowing You No More (Baby I'ma Do It Right) Every Woman In The World Mamma Mia 4Him Here I Am (Just When I Thought I Was Super Trouper For Future Generations Over You) Take A Chance On Me The Basics Of Life Just As I Am The Winner Takes It All 5 Seconds Of Summer Making Love Out Of Nothing At All Waterloo Amnesia One That You Love, The Abc Don't Stop Sweet Dreams The Look Of Love She Looks So Perfect Two Less Lonely People In The World ACDC 5 Stairsteps, The Akon Back In Black O-O-H Child Angel Highway To Hell 5th Dimension, The Be With You Moneytalks Aquarius Let The Sun Shine In Lonely You Shook Me All Night Long One Less Bell To Answer Right Now (Na Na Na) Ace Of Base Up Up And Away Akon Ftg. -

9.1 GB # Artist Title Length 01 2Pac Do for Love 04:37

Total tracks number: 958 Total tracks length: 67:52:34 Total tracks size: 9.1 GB # Artist Title Length 01 2pac Do For Love 04:37 02 2pac Thug Mansion 03:32 03 2pac Thugz Mansion (Real) 04:06 04 2pac Wonder If Heaven Got A Ghetto 04:36 05 2pac Daz Kurupt Baby Dont Cry Remix 05:20 06 3lw No More 04:20 07 7 Mile Do Your Thing 04:49 08 8Ball & MJG You Don't Want Drama 04:32 09 112 Anywhere 04:04 10 112 Crazy over You 05:20 11 112 Cupid (Radio Mix) 04:08 12 112 Cupid 04:08 13 112 It's Over Now 04:00 14 112 Love You Like I Did 04:17 15 112 Only You (Slow Remix) 04:11 16 504 Boys Wobble Wobble Edited 03:42 17 504 Boys Wobble 03:38 18 702 Get It Together 04:50 19 702 Where My Girls At 02:45 20 1000 Clowns (Not The) Greatest Rapper 03:48 21 A Boogie Wit da Hoodie Drowning (feat. Kodak Black) 03:28 22 Aaliyah 4 Page Letter 04:50 23 Aaliyah Age Aint Nothing But A Number 03:37 24 Aaliyah Are You That Somebody 04:24 25 Aaliyah Dust Yourself Off 04:41 26 Aaliyah Hot Like Fire (Timbaland Remix 04:32 27 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 04:31 28 Aaliyah I Don't Wanna 04:12 29 Aaliyah If Your Girl Only Knew 04:50 30 Aaliyah More Than A Woman 03:48 31 Aaliyah One In A Million 04:29 32 Aaliyah Rock The Boat 04:33 33 Aaliyah The One I Gave My Heart To 03:52 34 Aaliyah Try Again 04:39 35 Aaliyah Ft.