Terrorism and Community Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India's Child Soldiers

India’s Child Soldiers: Government defends officially designated terror groups’ record on the recruitment of child soldiers before the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child Asian Centre For Human Rights India’s Child Soldiers: Government defends officially designated terror groups’ record on the recruitment of child soldiers before the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child A shadow report to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict Asian Centre For Human Rights India’s Child Soldiers Published by: Asian Centre for Human Rights C-3/441-C, Janakpuri, New Delhi 110058 INDIA Tel/Fax: +91 11 25620583, 25503624 Website: www.achrweb.org Email: [email protected] First published March 2013 ©Asian Centre for Human Rights, 2013 No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher. ISBN : 978-81-88987-31-3 Suggested contribution Rs. 295/- Acknowledgement: This report is being published as a part of the ACHR’s “National Campaign for Prevention of Violence Against Children in Conflict with the Law in India” - a project funded by the European Commission under the European Instrument for Human Rights and Democracy – the European Union’s programme that aims to promote and support human rights and democracy worldwide. The views expressed are of the Asian Centre for Human Rights, and not of the European Commission. Asian Centre for Human Rights would also like to thank Ms Gitika Talukdar of Guwahati, a photo journalist, for the permission to use the photographs of the child soldiers. -

Thousands Bid Tearful Farewell to Fallen Soldier in Kashmir

www.thenorthlines.com www.epaper.northlines.com 3 DAY'S FORECAST JAMMU Date Min Temp Max Temp Weather 25-Feb 8.0 24.0 Mainly Clear sky 26-Feb 9.0 25.0 Mainly Clear sky 27-Feb 10.0 24.0 Mainly clear sky becoming partly cloudy towards evening or night 3 DAY'S FORECAST SRINAGAR Date Min Temp Max Temp Weather 25-Feb 0.0 13.0 Partly cloudy sky 26-Feb 1.0 14.0 Mainly Clear sky 27-Feb 2.0 13.0 Partly cloudy sky theCUJ organizes industrial visit northlines'JK fountainhead of 'Mahashivratri' celebrated with for students harmony, brotherhood' religious fervor The Department of Marketing & Minister of Forest, Environment and Mahashivratri 'Hairath', the most Supply Chain Management and HRM Ecology Choudhary Lal Singh has important annual festival of Kashmiri Departments of Central University of greeted people of the State on the Pandits was celebrated with religious 3 Jammu organized an Industrial visit 5 auspicious occasion of Shivratri. The 7 fervour and gaiety on Friday. The for the students ... INSIDE Minister joined .... festival began with .... Vol No: XXII Issue No. 49 25.02.2017 (Saturday) Daily Jammu Tawi Price ` 2/- Pages-12 Regd. No. JK|306|2014-16 Farooq Abdullah comes open in support of Thousands bid tearful farewell militants fighting for 'Kashmir's freedom' to fallen soldier in Kashmir NL CORRESPONDENT supply during Ramzan and Army chief pays rich tributes SRINAGAR, FEB 24 Diwali in Uttar Pradesh."It is regretful. Prime Minister NL CORRESPONDENT National Conference should talk in such a way BIJBEHARA (KASHMIR), FEB President and former chief that unites people rather than 24 minister Dr Farooq Abdullah creating a division. -

Kashmir Under the Afghans (1752-1819)

The International Journal Of Humanities & Social Studies (ISSN 2321 - 9203) www.theijhss.com THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL STUDIES Kashmir under the Afghans (1752-1819) Zaheen Research Scholar, Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi, India Abstract: The current paper ventures to understand the participation of Afghan rule in the regional transformation of Kashmir. The emergence of Afghans on the political forefront of Kashmir in the middle of 18th century was a direct outcome of Mughal administration. Afghan subadars tried to establish their political hegemony on the remnants of the Mughal structures which had already started dwindling under the later rulers of Mughal dynasty. Unlike pre-Mughal period, the political situation prevailing in the adjoining territories had comparatively greater impact on the political and administrative functioning of the region of Kashmir, itself. Though disgruntled nobility and internal administrative instability had a role to play in the frequently changing dynastic rule in post-Mughal Kashmir but the dynamics of political formations in the adjoining regions, especially in Lahore, Sind and Punjab determined the course of political history of Kashmir under and after the Afghans. The Afghans ruled Kashmir for 67 years which witnessed the rule of Pathan emperors at the Imperial court and around 26 subadars in the province of Kashmir. Though, it was an extension of Mughal administrative machinery and institutions but the position and functioning of the significant provincial officials like subadars, sahibkars, diwans, etc. underwent certain changes. The Afghan rulers didn't engage themselves in overhauling the administrative measures in the valley but continued with the systems pertaining to governance, initiated by early Mughals, except a few official positions especially in the revenue administration of the region. -

GENDER and MILITARISATION in KASHMIR By

BETWEEN DEMOCRACY AND NATION: GENDER AND MILITARISATION IN KASHMIR By Seema Kazi A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of PhD London School of Economics and Political Science The Gender Institute 2007 UMI Number: U501665 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U501665 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis focuses on the militarisation of a secessionist movement involving Kashmiri militants and Indian military forces in the north Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. The term militarisation in this thesis connotes the militarised state and, more primarily, the growing influence of the military within the state that has profound implications for state and society. In contrast to conventional approaches that distinguish between inter and intra-state military conflict, this thesis analyses India’s external and domestic crises of militarisation within a single analytic frame to argue that both dimensions are not mutually exclusive but have common political origins. Kashmir, this thesis further argues, exemplifies the intersection between militarisation’s external and domestic dimensions. -

Role of Select Courtiers and Officials at Lahore Darbar (1799- 1849)

ROLE OF SELECT COURTIERS AND OFFICIALS AT LAHORE DARBAR (1799- 1849) A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Social Sciences of the PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, PATIALA In Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY Supervised by Submitted by Dr. Kulbir Singh Dhillon Rajinder Kaur Professor & Head, Department of History, Punjabi University, Patiala DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, PATIALA 2011 CONTENTS Chapter Page No Certificate i Declaration ii Preface iii-xiv Chapter – I 1-45 INTRODUCTION Chapter – II 46-70 ESTABLISHMENT OF CENTRAL SECRETARIAT Chapter – III 71-99 FINANCIAL ADMINISTRATORS Chapter – IV 100-147 MILITARY COMMANDANTS Chapter – V 148-188 CIVIL ADMINISTRATORS Chapter – VI 189-235 DARBAR POLITICS AND INTRIGUES (1839-49) CONCLUSION AND FINDINGS 236-251 GLOSSARY 252-260 APPENDIX 261-269 BIBLIOGRAPHY 270-312 PREFACE Maharaja Ranjit Singh was like a meteor who shot up in the sky and dominated the scene for about half a century in the History of India. His greatness cannot be paralleled by any of his contemporaries. He was a benign ruler and always cared for the welfare of his subjects irrespective of their caste or creed. The Maharaja had full faith in the broad based harmony and cooperation with which the Hindus and the Muslims lived and maintained peace and prosperity. The evidence of the whole hearted co-operation of the Hindu Courtiers, Generals and Administrators is not far to seek. The spirit of Maharaja Ranjit Singh's rule was secular. In the present thesis I have selected only the Hindu Courtiers and Officials at the Lahore Darbar. -

For Correction.P65

AAO BANIYE GURSIKH PYARA Awau bxIey guris`K ipAwrw ies pusqk dy sB h`k sMgqW leI hI rwKvyN hn swD-sMgq ienHW dw pRcwr kr skdI hY Published By : GURMAT QUIZ PEOPLE 21/47, OLD RAJINDER NAGAR NEW DELHI-110060 Ph.: 9818219391, 011-45734363 November 2017 Compiled By : S. HARJINDER SINGH S. MANJIT SINGH S. HARSIMRAN SINGH S. HARMAN SINGH AAO BANIYE GURSIKH PYARA Awau bxIey guris`K ipAwrw GURBANI THOUGHTS 1. What is the meaning of “ivsUry”? Ans. Anxiety 2. What is the purpose of human life? Ans. To live a life full of humanity. 3. Gurmat does not give any importance to Zodiac signs palmistry or similar beliefs. True / False Ans. True 4. What is the meaning of “qUry” as it appears in Anand Sahib? Ans. Drums 5. Gurmat does not accept the presence of ghost or evil or good spirits ? True/ False Ans. True 6. What is the meaning of “guxI inDwn” as it appears in Japuji? Ans. Treasure of virtues 7. What is the meaning of “BwiKAw Bwau Apwr” as it appears in Japji? Ans. Language of Unending Love 8. According to Sikh principles Full Moon Day Black Night First day of month are not auspicious days. True /False Ans. True 9. In which Raag Bani of Anand Sahib in Sri Guru Granth Sahib is composed? Ans. Raag Ramkali 10. In which Raag Bani of Sukhmani Sahib in Sri Guru Granth Sahib is composed? Ans. Raag Gauri 11. In Sri Guru Granth Sahib Bani in Ragas starts from Page No 14. Ans. True 12. The central idea of a shabad in Sri Guru Granth Sahib is always in first line of that shabad. -

The Strategic Effects of Counterinsurgency Operations at Religious Sites: Lessons from India, Thailand, and Israel

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Winter 3-21-2013 The Strategic Effects of Counterinsurgency Operations at Religious Sites: Lessons from India, Thailand, and Israel Timothy L. Christopher Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Asian Studies Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Christopher, Timothy L., "The Strategic Effects of Counterinsurgency Operations at Religious Sites: Lessons from India, Thailand, and Israel" (2013). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 111. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.111 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Strategic Effects of Counterinsurgency Operations at Religious Sites: Lessons from India, Thailand, and Israel by Timothy L. Christopher A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Political Science Thesis Committee: David Kinsella, Chair Bruce Gilley Ronald Tammen Portland State University 2013 © 2013 Timothy L. Christopher ABSTRACT With the September 11th attacks on the World Trade Center buildings, the intersection of religious ideals in war has been at the forefront of the American discussion on war and conflict. The New York attacks were followed by the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan in October of 2001 in an attempt to destroy the religious government of the Taliban and capture the Islamic terrorist leader Osama bin Laden, and then followed by the 2003 invasion of Iraq, both in an attempt to fight terrorism and religious extremism. -

Afghan Rule in Kashmir (A Critical Review of Source Material)

Afghan Rule in Kashmir (A Critical Review of Source Material) Dissertation submitted to the University of Kashmir for the Award of the Degree of Master of Philosophy (M. Phil) In Department of History By Rouf Ahmad Mir Under the Supervision of Dr. Farooq Fayaz (Associate Professor) Post Graduate Department of History University Of Kashmir Hazratbal, Srinagar-6 2011 Post Graduate Department of History University of KashmirSrinagar-190006 (NAAC Accredited Grade “A”) CERTIFICATE This is to acknowledge that this dissertation, entitled Afghan Rule in Kashmir: A Critical Review of Source Material, is an original work by Rouf Ahmad, Scholar, Department of History, University of Kashmir, under my supervision, for the award of Pre-Doctoral Degree (M.Phil). He has fulfilled the entire statutory requirement for submission of the dissertation. Dr. Farooq Fayaz (Supervisor) Associate Professor Post Graduate Department of History University of Kashmir Srinagar-190006 Acknowledgement I am thankful to almighty Allah, our lord, Cherisher and sustainer. At the completion of this academic venture, it is my pleasure that I have an opportunity to express my gratitude to all those who have helped and encouraged me all the way. I express my gratitude and reverence to my teacher and guide Dr. Farooq Fayaz Associate Professor, Department of History University of Kashmir, for his generosity, supervision and constant guidance throughout the course of this study. It is with deep sense of gratitude and respect that I express my thanks to Prof. G. R. Jan (Professor of Persian) Central Asian Studies, University of Kashmir, my co-guide for his unique and inspiring guidance. -

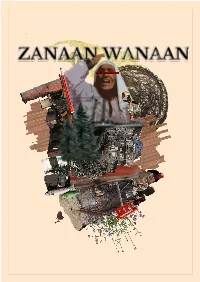

ZW ISSUE 1.Pdf

` OCTOBER 2020 Revisiting Dispossession and Loss in Kashmir new beginnings, radical possibilities Published By: Zanaan Wanaan Copyleft License: This issue may be used, reproduced, or translated freely for non- commercial purposes, with due acknowledgement and attributions. Date of Publication: October 2020 Website: zanaanwanaan.com Contact Information: [email protected] Cover Design: Kashmir Pop Art “tul kalam ti lyekh me hukm-e-Azaedi” pick up your pen and write me the decree of freedom -unknown ZW | Issue 1 | October 2020 3 This issue is dedicated to the women of Kashmir. To us, you embody and exemplify the true of resilience, in your survival, protest, mourning, remembrance, defiance, and also, in your silence. ZW | Issue 1 | October 2020 4 Editor’s Note From the last two decades, much of the feminist energy has, rightfully so, gone into establishing Kashmiri women’s capacity for agency. Although Kashmiri women’s positions have been shifting from one discursive context to the other, a consensus has emerged within the decolonial feminist scholarship over the powerful ways in which they have resisted the hegemonic structures. Kashmiri women have faced many challenges but, arguably, none more formidable than being denied the ownership of their narratives. This issue is an addition to the rapidly expanding body of work produced by Kashmiri women. Bringing together twenty women from various disciplines, ‘Revisiting Dispossession and Loss in Kashmir’ is a discussion on some of the most fundamental aspects of loss, coupled with seemingly mundane facets of unaccountability, injustice and violence. To this end, the sections that follow sketch loss through detailing and revisiting the Jammu massacre, enforced disappearances, domestic violence, memory, kitchen spaces, homelessness, faith, public architecture, childhood, and other important subjects. -

Perspectives on Guru Granth Sahib-Prelims

PERSPECTIVES ON SRI GURU GRANTH SAHIB 1 ISSN-2393-9745 JOURNAL PERSPECTIVES ON GURU GRANTH SAHIB Vol. IX 2014 Editor Dr. Balwant Singh Dhillon CENTRE ON STUDIES IN SRI GURU GRANTH SAHIB GURU NANAK DEV UNIVERSITY AMRITSAR - 143005 (INDIA) 2 PERSPECTIVES ON SRI GURU GRANTH SAHIB JOURNAL PERSPECTIVES ON GURU GRANTH SAHIB (Centre on Studies in Sri Guru Granth Sahib) Patron Dr. A.S. Brar Vice-Chancellor Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar Editor Dr. Balwant Singh Dhillon Editorial Board Dr. Gulzar Singh Kang Professor Dr. Jagbir Singh, Delhi Professor Dr. Jaspal Kaur Kaang, Chandigarh Professor Dr. Harbans Lal, Texas, U.S.A. Professor PERSPECTIVES ON SRI GURU GRANTH SAHIB 3 OUR CONTRIBUTORS 1. Dr. Balwant Singh Dhillon, Director, Centre on Studies in Sri Guru Granth Sahib, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar ñ 143005. 2. Dr. Gurnam Singh Sanghera, Honrary Visiting Professor, Centre on Studies in Sri Guru Granth Sahib, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar - 143005. 3. Dr. N. Muthumohan, Professor, Centre on Studies in Sri Guru Granth Sahib, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar. 4. Dr. D.P. Singh, 2516, Pollard Drive, Mississauga, ON L5C 3H1 Canada. 5. Dr. Ranbir Singh, Professor Emeritus Ohio State University, U.S.A. Before moving to USA in 1965, he worked in the Irrigation Department, Punjab as Assistant Engineer to Deputy Director Designs in the Bhakhra and Beas Design Directorate. 6. Dr. Harmeet Sethi, Associate Professor, Deptt. of History, Postgraduate Govt. College for Girls, Sector 42, Chandigarh. 7. Mrs. Ruby Vig, Senior Research Fellow, Centre on Studies in Sri Guru Granth Sahib, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar. -

Cascades of Violence War, Crime and Peacebuilding Across South Asia

CASCADES OF VIOLENCE WAR, CRIME AND PEACEBUILDING ACROSS SOUTH ASIA CASCADES OF VIOLENCE WAR, CRIME AND PEACEBUILDING ACROSS SOUTH ASIA JOHN BRAITHWAITE AND BINA D’COSTA Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN (print): 9781760461898 ISBN (online): 9781760461904 WorldCat (print): 1031051140 WorldCat (online): 1031374482 DOI: 10.22459/CV.02.2018 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image by Eli Vokounova, ‘Flow by Lucid Light’. This edition © 2018 ANU Press Contents Boxes and tables . vii Figures, maps and plates . ix Abbreviations . xiii Foreign terms . xix Preface . xxi Part I: Cascades on a broad canvas 1 . Introduction: Cascades of war and crime . 3 2 . Transnational cascades . 37 3 . Towards a micro–macro understanding of cascades . 93 4 . Cascades of domination . 135 Part II: South Asian cascades 5 . Recognising cascades in India and Kashmir . 177 6 . Mapping conflicts in Pakistan: State in turmoil . 271 7 . Macro to micro cascades: Bangladesh . .. 321 8 . Crime–war in Sri Lanka . 363 9 . Cascades to peripheries of South Asia . 393 Part III: Refining understanding of cascades 10 . Evaluating the propositions . 451 11 . Cascades of resistance to violence and domination . 487 12 . Conclusion: Cascades and complexity . -

Situation in Valley Tense but Under Control

www.thenorthlines.com www.epaper.northlines.com 3 FORECAST JAMMU Date Min Temp Max Temp Weather 29-May 29.0 40.0 Mainly Clear sky 30-May 29.0 39.0 Partly cloudy sky 31-May 27.0 38.0 Generally cloudy sky with possibility of rain or Thunderstorm or Duststorm 3 DAY'S FORECAST SRINAGAR Date Min Temp Max Temp Weather 29-May 13.0 31.0 Mainly Clear sky 30-May 13.0 30.0 Partly cloudy sky 31-May 13.0 28.0 Generally cloudy sky with possibility of rain or Thunderstorm or Duststorm theNPP committed to seek justice northlinesPace of ongoing developmental MoS inaugurates 63 KVA transformer for Jammu people: Mankotia works reviewed To declare Jammu Province a Minister of State for Finance and Planning, Labour and Employment, Minister for Rural Development and separate State National Panthers Panchayati Raj Abdul Haq Khan Party has initiated a "Haq Insaf Rath Ajay Nanada inaugurated a 63 KVA transformer at village Dub Pouni here today conducted extensive tour of Yatra". Today Yatra reached at Jib Ramban and Udhampur districts and 3 Thathi area participated ... 4 today. Concerned .... 7 INSIDE reviewed the pace .... Vol No: XXII Issue No. 126 29.05.2017 (Monday) Daily Jammu Tawi Price ` 2/- Pages-12 Regd. No. JK|306|2017-19 We found a 'permanent solution' Sabzar's killing 'Dirty war' in Kashmir to be fought Situation in valley tense with innovative ways: Army Chief for Kashmir: Home Minister NL CORRESPONDENT but under control: IGP NEW DELHI, MAY 28 inviting separatist refused to elaborate on what The Indian Army is groups for talks on kind of solution the BJP facing a "dirty war" in Kashmir and said government has found for SRINAGAR, MAY 28 (KNS) and his associate Faizan said happened due to Jammu and Kashmir whoever wanted to Jammu and Kashmir, which Muzaffar of Tral.