The Casamance Conflict: Un-Imagining a Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapport EV 2009 Cartes Rev-Mai 2011 Mb MF__Dsdsx

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple-Un But-Une Foi ---------- MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE ET DES FINANCES ---------- Cellule de Suivi du Programme de Lutte contre la Pauvreté (CSPLP) ---------- Projet d’Appui à la Stratégie de Réduction de la Pauvreté (PASRP) Avec l’appui de l’union européenne ENQUETE VILLAGES DE 2009 SUR L'ACCES AUX SERVICES SOCIAUX DE BASE Rapport final Dakar, Décembre 2009 SOMMAIRE I. CONTEXTE ET JUSTIFICATIONS _____________________________________________ 3 II. OBJECTIF GLOBAL DE L’ENQUETE VILLAGES __________________________________ 3 III. ORGANISATION ET METHODOLOGIE ________________________________________ 5 III.1 Rationalité ______________________________________________________________ 5 III.2 Stratégie ________________________________________________________________ 5 III.3 Budget et ressources humaines _____________________________________________ 7 III.4 Calendrier des activités ____________________________________________________ 7 III.5 Calcul des indices et classement des communautés rurales _______________________ 9 IV. Analyse des premiers résultats de l’enquête _______________________________ 10 V. ACCES ET EXISTENCE DES SERVICES SOCIAUX DE BASE _________________________ 11 VI. Accès et fonctionnalité des services sociaux de base ________________________ 14 VII. Disparités régionales et accès aux services sociaux de base __________________ 16 VII.1 Disparité régionale de l’accès à un lieu de commerce ___________________________ 16 VII.2 Disparité régionale de l’accès à un point d’eau potable _________________________ -

Medicinal Plants of Guinea-Bissau: Therapeutic Applications, Ethnic Diversity and Knowledge Transfer

Journal of Ethnopharmacology 183 (2016) 71–94 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Ethnopharmacology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jep Medicinal plants of Guinea-Bissau: Therapeutic applications, ethnic diversity and knowledge transfer Luís Catarino a, Philip J. Havik b,n, Maria M. Romeiras a,c,nn a University of Lisbon, Faculty of Sciences, Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Changes (Ce3C), Lisbon, Portugal b Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, Instituto de Higiene e Medicina Tropical, Global Health and Tropical Medicine, Rua da Junqueira no. 100, 1349-008 Lisbon, Portugal c University of Lisbon, Faculty of Sciences, Biosystems and Integrative Sciences Institute (BioISI), Lisbon, Portugal article info abstract Article history: Ethnopharmacological relevance: The rich flora of Guinea-Bissau, and the widespread use of medicinal Received 10 September 2015 plants for the treatment of various diseases, constitutes an important local healthcare resource with Received in revised form significant potential for research and development of phytomedicines. The goal of this study is to prepare 21 February 2016 a comprehensive documentation of Guinea-Bissau’s medicinal plants, including their distribution, local Accepted 22 February 2016 vernacular names and their therapeutic and other applications, based upon local notions of disease and Available online 23 February 2016 illness. Keywords: Materials and methods: Ethnobotanical data was collected by means of field research in Guinea-Bissau, Ethnobotany study of herbarium specimens, and a comprehensive review of published works. Relevant data were Indigenous medicine included from open interviews conducted with healers and from observations in the field during the last Phytotherapy two decades. Knowledge transfer Results: A total of 218 medicinal plants were documented, belonging to 63 families, of which 195 are West Africa Guinea-Bissau native. -

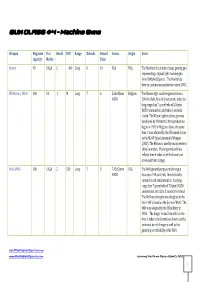

Machine Guns

GUN CLASS #4 – Machine Guns Weapon Magazine Fire Recoil ROF Range Reloads Reload Ammo Origin Notes capacity Modes Time Morita 99 FA,SA 2 400 Long 6 10 N/A N/A The Morita is the standard issue gaming gun representing a typical light machine gun from Battlefield Sports. The Morita has been in continuous manufacture since 2002. FN Minimi / M249 200 FA 2 M Long 7 6 5.56x45mm Belgium The Minimi light machine gun features a NATO 200 shot belt, fires fully automatic only, has long range, has 7 spare belts of 5.56mm NATO ammunition, and takes 6 seconds reload. The Minimi light machine gun was developed by FN Herstal. Mass production began in 1982 in Belgium. About the same time it was adopted by the US Armed forces as the M249 Squad Automatic Weapon (SAW). The Minimi is used by many western allied countries. The longer reload time reflects time it takes to let the barrel cool down and then change. M60 GPMG 100 FA,SA 2 550 Long 7 8 7.62x51mm USA The M60 general purpose machine gun NATO features a 100 shot belt, fires both fully automatic and semiautomatic, has long range, has 7 spare belts of 7.62mm NATO ammunition and takes 8 seconds to reload. The M60 machine gun was designed in the late 1940's based on the German MG42. The M60 was adopted by the US military in 1950. .The longer reload time reflects the time it takes to let barrel cool down and the awkward barrel change as well as the general poor reliability of the M60. -

Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850

The Texture of Change: Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Benjamin, Jody A. 2016. The Texture of Change: Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493374 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Texture of Change: Cloth Commerce and History in West Africa, 1700-1850 A dissertation presented by Jody A. Benjamin to The Department of African and African American Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of African and African American Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2016 © 2016 Jody A. Benjamin All rights reserved. Dissertation Adviser: Professor Emmanuel Akyeampong Jody A. Benjamin The Texture of Change: Cloth Commerce and History in West Africa, 1700-1850 Abstract This study re-examines historical change in western Africa during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries through the lens of cotton textiles; that is by focusing on the production, exchange and consumption of cotton cloth, including the evolution of clothing practices, through which the region interacted with other parts of the world. It advances a recent scholarly emphasis to re-assert the centrality of African societies to the history of the early modern trade diasporas that shaped developments around the Atlantic Ocean. -

Senegal Page 155 8

© 2003 Center for Reproductive Rights www.reproductiverights.org formerly the Center for Reproductive Law and Policy LAWS AND POLICIES AFFECTING THEIR REPRODUCTIVE LIVES SENEGAL PAGE 155 8. Senegal Statistics GENERAL Population I The total population of Senegal is approximately 9 million.1 I The average annual population growth rate between 1995 and 2000 is estimated to be 2.7%.2 I In 1995, women comprised 52% of the population.3 I In 1995, 42% of the population resided in urban areas.4 Territory I Senegal covers an area of 196,722 square kilometers.5 Economy I In 1997,the estimated per capita gross national product (GNP) was U.S.$550.6 I Between 1990 and 1997,the average annual growth rate of the gross domestic product (GDP) was 2.4%.7 I Approximately 40% of the population have access to primary health care.8 I The government allocates 6.5% of the national budget to the health sector.9 Employment I In 1997,women comprised 43% of the workforce, compared to 42% in 1980.10 I The distribution of women in the different sectors of the economy in 1994 was as follows: 87% in agriculture, 3% in industry,and 10% in services.11 I In 1991, the unemployment rate for women increased from 23.1% in 1988 to 26.6%.12 WOMEN’S STATUS I In 1997,the average life expectancy for women was 52.3 years, compared to 50.3 for men.13 I The adult illiteracy rate was 77% for women, compared to 57% for men.14 I In 1997, 46% of married women lived in polygamous unions.15 I The average age at first marriage for women aged 25-49 was 17.4 years.16 Among these women, 15% were married upon reach- ing 15 years, and 50% upon reaching 18 years.17 FEMALE MINORS AND ADOLESCENTS I Approximately 45% of the population is under 15 years old.18 I In 1995, primary school enrollment for school-aged girls was 50%, compared to 67% for boys. -

White Paper for a Sustainable Peace in Casamance

White Paper for a Sustainable Peace in Casamance Perspectives from Women and Local Populations August 2019 Content 3. Acronyms & Abbreviations 4. Acknowledgements 5. Foreword 7. Cry For Action Of The Women Of Casamance! 8. Preface 9. Introduction 9. Context 11. Historical background of the conflict and the peace process 13. The Conflict’s Impacts On Local Populations, Women And Youth 13. Socioeconomic and environmental impacts 15. Casamance populations’ perceptions and feelings of exclusion 17. The conflict’s specific impacts on women 18. A permanent insecurity 19. Strategies And Perspectives From Civil Society 20. Civil society actors 21. Addressing challenges and establishing peace 23. Actions and approaches 25. Conditions for effective and inclusive participation 26. Women’s participation in peace processes 26. The mediation role of women of Casamance 27. La Plateforme des Femmes pour la Paix en Casamance (PFPC) 28. Senegambia Forum 29. Breaking down barriers and strengthening support across women throughout Senegal 30. Recommendations for a definitive & sustainable peace in Casamance 34. Bibliography 35. Annexes 49. Endnotes Acronyms & Abbreviations AFUDES Association of United Brothers for the Economic and Social Development of the Fogny ASC Sports and Cultural Association AJAEDO Association des Jeunes Agriculteurs et Éleveurs du Département d'Oussouye AJWS American Jewish World Service (NGO) ANRAC Agence nationale pour la Relance des Activités économiques en Casamance ANSD Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie -

Guinea-Bissau After Vieira: Challenges and Opportunities

THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS 20/1999 Guinea-Bissau after Vieira: Challenges and Opportunities On 7 June 1998, an army mutiny led by former Chief of Staff, General Ansumane Mane, plunged the Republic of Guinea-Bissau into a devastating civil war. The coup aimed to oust President Joao Bernardo Vieira, who had come to power in a military coup against Luis Cabral in 1980 and had subsequently won the country's first multiparty elections in 1994. The civil war that followed Mane's mutiny changed the framework of the ongoing transformation process in the former socialist-orientated Guinea-Bissau. It also engulfed the subregion drawing Senegal, Guinea and The Gambia into the power struggle in Guinea- Bissau. In May 1999, after a peace process had already been did not install a military regime after he came to negotiated and partially implemented, Mane's forces power. With the beginning of democratic transition launched another attack on Vieira, and finally in 1990, the military lost its remaining privileges and succeeded in ousting the incumbent leader. Although became part of the marginalised population. Major this coup can be seen as a setback for peace and sections of the army started relying on proceeds from reconciliation in Guinea-Bissau, the new political illicit arms deals with the Casamance rebels and situation that resulted from Vieira's overthrow at least cannabis sales. provided a chance to end a hitherto paralysing state of 'no peace-no war' — akin to the Angolan situation The regional dimension after the Lusaka Accords. The new power G iven Mane's control over major sections of the army, constellation under Mane may well give Vieira's Vieira had to fight the rebellion with the military rather disappointing democratisation assistance of Guinea (400 soldiers) and process fresh impetus. -

Livelihood Zone Descriptions

Government of Senegal COMPREHENSIVE FOOD SECURITY AND VULNERABILITY ANALYSIS (CFSVA) Livelihood Zone Descriptions WFP/FAO/SE-CNSA/CSE/FEWS NET Introduction The WFP, FAO, CSE (Centre de Suivi Ecologique), SE/CNSA (Commissariat National à la Sécurité Alimentaire) and FEWS NET conducted a zoning exercise with the goal of defining zones with fairly homogenous livelihoods in order to better monitor vulnerability and early warning indicators. This exercise led to the development of a Livelihood Zone Map, showing zones within which people share broadly the same pattern of livelihood and means of subsistence. These zones are characterized by the following three factors, which influence household food consumption and are integral to analyzing vulnerability: 1) Geography – natural (topography, altitude, soil, climate, vegetation, waterways, etc.) and infrastructure (roads, railroads, telecommunications, etc.) 2) Production – agricultural, agro-pastoral, pastoral, and cash crop systems, based on local labor, hunter-gatherers, etc. 3) Market access/trade – ability to trade, sell goods and services, and find employment. Key factors include demand, the effectiveness of marketing systems, and the existence of basic infrastructure. Methodology The zoning exercise consisted of three important steps: 1) Document review and compilation of secondary data to constitute a working base and triangulate information 2) Consultations with national-level contacts to draft initial livelihood zone maps and descriptions 3) Consultations with contacts during workshops in each region to revise maps and descriptions. 1. Consolidating secondary data Work with national- and regional-level contacts was facilitated by a document review and compilation of secondary data on aspects of topography, production systems/land use, land and vegetation, and population density. -

Initial Report Submitted by Senegal Under Article 35 of the Convention, Due in 2012*

United Nations CRPD/C/SEN/1 Convention on the Rights Distr.: General 27 July 2018 of Persons with Disabilities English Original: French English, French, Russian and Spanish only Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Initial report submitted by Senegal under article 35 of the Convention, due in 2012* [Date received: 23 March 2015] * The present document is being issued without formal editing. GE.18-12499 (E) 280818 030918 CRPD/C/SEN/1 Contents Page General introduction ...................................................................................................................... 3 Articles 1 to 4: General principles of the Convention ................................................................... 3 Article 5. Equality and non-discrimination ................................................................................... 11 Article 6: Women with disabilities ................................................................................................ 13 Article 7: Children with disabilities .............................................................................................. 16 Article 8: Awareness-raising ......................................................................................................... 17 Article 9: Accessibility .................................................................................................................. 18 Article 10: Right to life ................................................................................................................. 19 Article -

Algeria Country Report

SALW Guide Global distribution and visual identification Algeria Country report https://salw-guide.bicc.de Weapons Distribution SALW Guide Weapons Distribution The following list shows the weapons which can be found in Algeria and whether there is data on who holds these weapons: AK-47 / AKM G MAT 49 G AK-74 U MP UZI G Beretta M 12 U Norinco Type 81 G Dragunov SVD U PK G DShk G RPD G M60 G Simonov SKS G MAS 49 U Strela (SA-7 / SA-14) G N MAS 49/56 U Tokarev TT-30/TT-33 U Explanation of symbols Country of origin Licensed production Production without a licence G Government: Sources indicate that this type of weapon is held by Governmental agencies. N Non-Government: Sources indicate that this type of weapon is held by non-Governmental armed groups. U Unspecified: Sources indicate that this type of weapon is found in the country, but do not specify whether it is held by Governmental agencies or non-Governmental armed groups. It is entirely possible to have a combination of tags beside each country. For example, if country X is tagged with a G and a U, it means that at least one source of data identifies Governmental agencies as holders of weapon type Y, and at least one other source confirms the presence of the weapon in country X without specifying who holds it. Note: This application is a living, non-comprehensive database, relying to a great extent on active contributions (provision and/or validation of data and information) by either SALW experts from the military and international renowned think tanks or by national and regional focal points of small arms control entities. -

Violent Conflicts and Civil Strife in West Africa: Causes, Stability Challenges and Prospects

Annan, N 2014 Violent Conflicts and Civil Strife in West Africa: Causes, stability Challenges and Prospects. Stability: International Journal of Security & Development, 3(1): 3, pp. 1-16, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/sta.da RESEARCH ARTICLE Violent Conflicts and Civil Strife in West Africa: Causes, Challenges and Prospects Nancy Annan* The advent of intra-state conflicts or ‘new wars’ in West Africa has brought many of its economies to the brink of collapse, creating humanitarian casualties and concerns. For decades, countries such as Liberia, Sierra Leone, Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea- Bissau were crippled by conflicts and civil strife in which violence and incessant killings were prevalent. While violent conflicts are declining in the sub-region, recent insurgencies in the Sahel region affecting the West African countries of Mali, Niger and Mauritania and low intensity conflicts surging within notably stable countries such as Ghana, Nigeria and Senegal sends alarming signals of the possible re-surfacing of internal and regional violent conflicts. These conflicts are often hinged on several factors including poverty, human rights violations, bad governance and corruption, ethnic marginalization and small arms proliferation. Although many actors including the ECOWAS, civil society and international community have been making efforts, conflicts continue to persist in the sub-region and their resolution is often protracted. This paper posits that the poor understanding of the fundamental causes of West Africa’s violent conflicts and civil strife would likely cause the sub-region to continue experiencing and suffering the brunt of these violent wars. Introduction 24). While violent conflicts are declining in The transformation from inter-state to intra- the sub-region, recent insurgencies in the state conflict from the latter part of the 20th Sahel region affecting the West African coun- Century in West Africa brought a number of tries of Mali, Niger and Mauritania sends its economies to near collapse. -

Z I G U I N C H O R 2 0

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple – Un But – Une Foi ------------------ MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE, DES FINANCES ET DU PLAN Z ------------------ AGENCE NATIONALE DE LA STATISTIQUE I ET DE LA DEMOGRAPHIE ----------------- G Service Régional de la Statistique et de la Démographie de Ziguinchor U I N C H O R 2 0 SITUATION ECONOMIQUE ET SOCIALE REGIONALE 1 2016 6 Octobre 2019 COMITE DE DIRECTION Directeur Général BABACAR NDIR Directeur Général Adjoint ALLÉ NAR DIOP Conseiller à l’Action Régionale MAMADOU DIENG Président du CLV SECKENE SENE COMITE DE REDACTION Chef du Service Régional Jean Rodrigue MALOU Adjoint au Chef du Service Régional Alassane AW Le point focal du siège qui a aidé à la rédaction de Bintou Diack Ly la SESR COMITE DE LECTURE ET DE VALIDATION SECKENE SENE DIRECTION GENERALE AMADOU FALL DIOUF CPCCI SERGE MANEL DSDS IDRISSA DIAGNE ENSAE MAMADOU BALDE ENSAE OMAR SENE ENSAE AWA CISSOKHO FAYE DSDS MM. RAMLATOU DIALLO DSECN MANDY DANSOKHO ENSAE MAMADOU DIENG CAR NDEYE BINTA DIEME COLY DSDS MAMADOU AMOUZOU OPCV ADJIBOU OPPAH BARRY OPCV BINTOU DIACK LY DSECN MAMADOU BAH DMIS EL HADJI MALICK GUEYE DMIS ABDOULAYE TALL OPCV MOMATH CISSE CGP MAHMOUTH DIOUF DSDS MORY DIOUSS DSDS ATOUMANE FALL DSDS ALAIN FRANCOIS DIATTA DMIS SES de Ziguinchor, Ed. 2016 AGENCE NATIONALE DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE LA DEMOGRAPHIE Rocade Fann –Bel-air–Cerf-volant – Dakar Sénégal. B.P. 116 Dakar R.P. - Sénégal Téléphone (221) 33 869 21 39 - Fax (221) 33 824 36 15 Site web : www.ansd.sn ; Email: [email protected] Distribution : Division de la Documentation, de la Diffusion et des Relations avec les Usagers Service Régional de la Statistique et de la Démographie de Ziguinchor Adresse : Tilene Complémentaire Tél : 33 991 12 58 B.P.