1 'As Good a Free State Citizen As Any They Had'? the Disbanded Members of the Royal Irish Constabulary Unpublished Paper By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

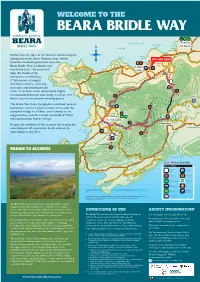

BEARA BRIDLEWAY A1 MAP Urhan

WELCOME TO THE BEARA BRIDLE WAY KENMARE BAY Eyeries Ardacluggin Pallas Point Na haoraí Carrigeel Strand Etched into the sides of the Miskish and Knockgour Travara Rahis Pt mountains of the Slieve Miskish range which Strand YOU ARE HERE knuckles the Beara peninsula west, the Urhan Urhan Beara Bridle Way is Ireland’s first Travaud Urhan Inn Valley ever horse trail. The main trail Gortahig Iorthan hugs the flanks of the Caherkeen mountains, overlooking 90m 17 kilometres of rugged mountain scenery, stunning y seascapes and dazzling island le Wa a Brid ar views. It includes some optional but highly Be recommended detours that climb to access even 230m Trekking better vistas from elevated viewing points. 220m Knockoura Centre 490m The Bridle Way links Clonglaskin townland several kilometres west of Castletownbere town with the Knockgour colourful village of Allihies, once famous for its 400m Teernahilane coppermines, and the coastal townland of Urhan Allihies near picturesque Eyeries village. Na hAilichí 320m 90m Despite the wildness of the scenery, the terrain has 70m Clonglaskin something for all experience levels and can be Beach To Castletownbere Ballydonegan View B&B undertaken at any pace. Beach Holiday Homes Gour 330m R575 Foher Cahermeeleboe 190m URHAN TO ALLIHIES R575 Bealbarnish Gap BANTRY BAY Beara Bridle Way KEY TO SYMBOLS Bridleway Parking Gates View Point Restaurant Accommodation Swimming B&B for Horses Bar Drinking water Post Office for horses Includes Ordnance Survey Ireland data reproduced under OSi Licence number 2016/06/CCMA/CorkCountyCouncil Trekking Centre Unauthorised reproduction infringes Ordnance Survey Ireland and Government of Ireland copyright. © Ordnance Survey Ireland, 2016 The Bridle Way follows an old road originally built to enable villagers from Urhan and Eyeries to commute to the Allihies mines. -

Whats on CORK

Festivals CORK CITY & COUNTY 2019 DATE CATEGORY EVENT VENUE & CONTACT PRICE January 5 to 18 Mental Health First Fortnight Various Venues Cork City & County www.firstfortnight.ie January 11 to 13 Chess Mulcahy Memorial Chess Metropole Hotel Cork Congress www.corkchess.com January 12 to 13 Tattoo Winter Tattoo Bash Midleton Park Hotel www.midletontattooshow.ie January 23 to 27 Music The White Horse Winter The White Horse Ballincollig Music Festival www.whitehorse.ie January TBC Bluegrass Heart & Home, Old Time, Ballydehob Good Time & Bluegrass www.ballydehob.ie January TBC Blues Murphy’s January Blues Various Locations Cork City Festival www.soberlane.com Jan/Feb 27 Jan Theatre Blackwater Valley Fit Up The Mall Arts Centre Youghal 3,10,17 Feb Theatre Festival www.themallartscentre.com Jan/Feb 28 to Feb 3 Burgers Cork Burger Festival Various Venues Cork City & County www.festivalscork.com/cork- burger-festival Jan/Feb 31 to Feb 2 Brewing Cask Ales & Strange Franciscan Well North Mall Brew Festival www.franciscanwell.com February 8 to 10 Arts Quarter Block Party North & South Main St Cork www.makeshiftensemble.com February TBC Traditional Music UCC TadSoc Tradfest Various Venues www.tradsoc.com February TBC Games Clonakilty International Clonakilty Games Festival www.clonakiltygamesfestival.co m February Poetry Cork International Poetry Various Venues Festival www.corkpoetryfest.net Disclaimer: The events listed are subject to change please contact the venue for further details | PAGE 1 OF 11 DATE CATEGORY EVENT VENUE & CONTACT PRICE Feb/Mar -

Tilley Award 2005

Tilley Award 2005 Application form The following form must be competed in full. Failure to do so will result in disqualification from the competition. Please send competed application forms to Tricia Perkins at [email protected] All entries must be received by noon on the 29 April 2005. Entries received after that date will not be accepted under any circumstances. Any queries on the application process should be directed to Tricia Perkins on 0207 035 0262. 1. Details of application Title of the project ‘The Human Chassis Number’ Name of force/agency/CDRP: Hertfordshire Constabulary – Central Area Road Policing Tactical Team Name of one contact person with position/rank (this should be one of the authors): Sergeant Greg O’Toole 742 Email address: greg.o’[email protected] Full postal address: Welwyn Garden City Police station The Campus Welwyn Garden City Hertfordshire AL8 6AF Telephone number: 01707 - 638035 Fax number 01707 638009 Name of endorsing senior representatives(s) Simon Ash Position and rank of endorsing senior representatives(s) Deputy Chief Constable Full address of endorsing senior representatives(s) Hertfordshire Police Headquarters Stanborough Road Welwyn Garden City Hertfordshire AL8 6XF 2. Summary of application 1 ‘THE HUMAN CHASSIS NUMBER’ SCANNING In September 2003, Hertfordshire Constabulary set up a road policing team to proactively target criminals using motor vehicles to commit crime. The team found that the potential benefit of Automatic Number-Plate Recognition (ANPR) technology was not being fully realised due to technical limitations. There was no capability to link intelligence, on the national ANPR databases, with known individuals in the absence of a number-plate match. -

The Origins and Expansion of the O'shea Clan

The Origins and Expansion of the O’Shea Clan At the beginning of the second millennium in the High Kingship of Brian Boru, there were three distinct races or petty kingdoms in what is now the County of Kerry. In the north along the Shannon estuary lived the most ancient of these known as the Ciarraige, reputed to be descendants of the Picts, who may have preceded the first Celts to settle in Ireland. On either side of Dingle Bay and inland eastwards lived the Corcu Duibne1 descended from possibly the first wave of Celtic immigration called the Fir Bolg and also referred to as Iverni or Erainn. The common explanation of Fir Bolg is ‘Bag Men’ so called as they allegedly exported Irish earth in bags to spread around Greek cities as protection against snakes! However as bolg in Irish means stomach, generations of Irish school children referred to them gleefully as ‘Fat bellies’ or worse. Legend has it that these Fir Bolg, as we will see possibly the ancestors of the O’Shea clan, landed in Cork. Reputedly small, dark and boorish they settled in Cork and Kerry and were the authors of the great Red Branch group of sagas and the builders of great stone fortresses around the seacoasts of Kerry. Finally around Killarney and south of it lived the Eoganacht Locha Lein, descendants of a later Celtic visitation called Goidels or Gaels. Present Kerry boundary (3) (2) (1) The territories of the people of the Corcu Duibne with subsequent sept strongholds; (1) O’Sheas (2) O’Falveys (3) O’Connells The Corcu Duibne were recognised as a distinct race by the fifth or sixth century AD. -

BMH.WS1737.Pdf

ROINN COSANTA BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21 STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1,757. Witness Seamus Fitzgerald, "Carrigbeg", Summerhill. CORK. Identity. T.D. in 1st Dáll Éireann; Chairman of Parish Court, Cobh; President of East Cork District Court.Court. Subject.District 'A' Company (Cobh), 4th Battn., Cork No. 1 Bgde., - I.R.A., 1913 1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil. File No S. 3,039. Form BSM2 P 532 10006-57 3/4526 BUREAUOFMILITARYHISTORY1913-21 BURO STAIREMILEATA1913-21 No. W.S. ORIGINAL 1737 STATEMENT BY SEAMUS FITZGERALD, "Carrigbeg". Summerhill. Cork. On the inauguration of the Irish Volunteer movement in Dublin on November 25th 1913, I was one of a small group of Cobh Gaelic Leaguers who decided to form a unit. This was done early in l9l4, and at the outbreak of the 1914. War Cobh had over 500 Volunteers organised into six companies, and I became Assistant Secretary to the Cobh Volunteer Executive at the age of 17 years. When the split occurred in the Irish Volunteer movement after John Redmond's Woodenbridge recruiting speech for the British Army - on September 20th 1914. - I took my stand with Eoin MacNeill's Irish Volunteers and, with about twenty others, continued as a member of the Cobh unit. The great majority of the six companies elected, at a mass meeting in the Baths Hall, Cobh, to support John Redmond's Irish National Volunteers and give support to Britain's war effort. The political feelings of the people and their leaders at this tint, and the events which led to this position in Cobh, so simply expressed in the foregoing paragraphs, and which position was of a like pattern throughout the country, have been given in the writings of Stephen Gwynn, Colonel Maurice Moore, Bulmer Hobson, P.S. -

United Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross DIOCESAN MAGAZINE

THE CHURCH OF IRELAND United Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross DIOCESAN MAGAZINE A Symbol of ‘Hope’ May 2020 €2.50 w flowers for all occasions w Individually w . e Designed Bouquets l e g a & Arrangements n c e f lo Callsave: ri st 1850 369369 s. co m The European Federation of Interior Landscape Groups •Fresh & w w Artificial Plant Displays w .f lo •Offices • Hotels ra ld •Restaurants • Showrooms e c o r lt •Maintenance Service d . c •Purchase or Rental terms o m Tel: (021) 429 2944 bringing interiors alive 16556 DOUGLAS ROAD, CORK United Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross DIOCESAN MAGAZINE May 2020 Volume XLV - No.5 The Bishop writes… Dear Friends, Last month’s letter which I published online was written the day after An Taoiseach announced that gatherings were to be limited to 100 people indoors and to 500 people outdoors. Since then we have had a whirlwind of change. Many have faced disappointments and great challenges. Still others find that the normality of their lives has been upended. For too many, illness they have already been living with has been complicated, and great numbers have struggled with or are suffering from COVID-19. We have not been able to give loved ones who have died in these times the funerals we would like to have arranged for them. Those working in what have been classed as ‘essential services’, especially those in all branches of healthcare, are working in a new normality that is at the limit of human endurance. Most of us are being asked to make our contribution by heeding the message: ‘Stay at home’ These are traumatic times for everyone. -

Taxi Kenmare

Page 01:Layout 1 14/10/13 4:53 PM Page 1 If it’s happening in Kenmare, it’s in the Kenmarenews FREE October 2013 www.kenmarenews.biz Vol 10, Issue 9 kenmareDon’t miss All newsBusy month Humpty happening for Dumpty at Internazionale Duathlon Kenmare FC ...See GAA ...See page page 40 ...See 33 page 32 SeanadóirSenator Marcus Mark O’Dalaigh Daly SherryAUCTIONEERS FitzGerald & VALUERS T: 064-6641213 Daly Coomathloukane, Caherdaniel Kenmare • 3 Bed Detached House • Set on c.3.95 acres votes to retain • Sea Views • In Need of Renovation •All Other Lots Sold atAuction Mob: 086 803 2612 the Seanad • 3.5 Miles to Caherdaniel Village Clinics held in the Michael Atlantic Bar and all € surrounding Offers In Excess of: 150,000 Healy-Rae parishes on a T.D. regular basis. Sean Daly & Co Ltd EVERY SUNDAY NIGHT IN KILGARVAN: Insurance Brokers HEALY-RAE’S MACE - 9PM – 10PM Before you Renew your Insurance (Household, Motor or Commercial) HEALY-RAE’S BAR - 10PM – 11PM Talk to us FIRST - 064-6641213 We Give Excellent Quotations. Tel: 064 66 32467 • Fax : 064 6685904 • Mobile: 087 2461678 Sean Daly & Co Ltd, 34 Henry St, Kenmare T: 064-6641213 E-mail: [email protected] • Johnny Healy-Rae MCC 087 2354793 Cllr. Patrick TAXI KENMARE Denis & Mags Griffin O’ Connor-ScarteenM: 087 2904325 Sneem & Kilgarvan 087 614 7222 Wastewater Systems See Notes on Page 16 Page 02:Layout 1 14/10/13 4:55 PM Page 1 2 | Kenmare News Mary Falvey was the winner of the baking Denis O'Neill competition at and his daughter Blackwater Sports, Rebecca at and she is pictured Edel O'Neill here with judges and Stephen Steve and Louise O'Brien's Austin. -

Secret Societies and the Easter Rising

Dominican Scholar Senior Theses Student Scholarship 5-2016 The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising Sierra M. Harlan Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Harlan, Sierra M., "The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising" (2016). Senior Theses. 49. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POWER OF A SECRET: SECRET SOCIETIES AND THE EASTER RISING A senior thesis submitted to the History Faculty of Dominican University of California in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in History by Sierra Harlan San Rafael, California May 2016 Harlan ii © 2016 Sierra Harlan All Rights Reserved. Harlan iii Acknowledgments This paper would not have been possible without the amazing support and at times prodding of my family and friends. I specifically would like to thank my father, without him it would not have been possible for me to attend this school or accomplish this paper. He is an amazing man and an entire page could be written about the ways he has helped me, not only this year but my entire life. As a historian I am indebted to a number of librarians and researchers, first and foremost is Michael Pujals, who helped me expedite many problems and was consistently reachable to answer my questions. -

Robert John Lynch-24072009.Pdf

THE NORTHERN IRA AND THE EARY YEARS OF PARTITION 1920-22 Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Stirling. ROBERT JOHN LYNCH DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY DECEMBER 2003 CONTENTS Abstract 2 Declaration 3 Acknowledgements 4 Abbreviations 5 Chronology 6 Maps 8 Introduction 11 PART I: THE WAR COMES NORTH 23 1 Finding the Fight 2 North and South 65 3 Belfast and the Truce 105 PART ll: OFFENSIVE 146 4 The Opening of the Border Campaign 167 5 The Crisis of Spring 1922 6 The Joint-IRA policy 204 PART ILL: DEFEAT 257 7 The Army of the North 8 New Policies, New Enemies 278 Conclusion 330 Bibliography 336 ABSTRACT The years i 920-22 constituted a period of unprecedented conflct and political change in Ireland. It began with the onset of the most brutal phase of the War of Independence and culminated in the effective miltary defeat of the Republican IRA in the Civil War. Occurring alongside these dramatic changes in the south and west of Ireland was a far more fundamental conflict in the north-east; a period of brutal sectarian violence which marked the early years of partition and the establishment of Northern Ireland. Almost uniquely the IRA in the six counties were involved in every one of these conflcts and yet it can be argued was on the fringes of all of them. The period i 920-22 saw the evolution of the organisation from a peripheral curiosity during the War of independence to an idealistic symbol for those wishing to resolve the fundamental divisions within the Sinn Fein movement which developed in the first six months of i 922. -

Essays in History}

3/31/2021 The Black and Tans: British Police and Auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence, 1920-1921 — {essays in history} {essays in history} The Annual Journal produced by the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia The Black and Tans: British Police and Auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence, 1920-1921 Volume 45 (2012) Reviewed Work(s) www.essaysinhistory.net/the-black-and-tans-british-police-and-auxiliaries-in-the-irish-war-of-independence-1920-1921/ 1/5 3/31/2021 The Black and Tans: British Police and Auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence, 1920-1921 — {essays in history} The Black and Tans: British Police and Auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence, 1920-1921. By David Leeson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011). Pp. 294. Hardcover, $52.98. Scholars have included the Irish War of Independence in their appraisals of modern Irish history since the war ended in the early 1920s. David M. Leeson, a historian at Laurentian University, examines the less discussed units of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) — that is the Black and Tans and the Auxiliary Division (ADRIC) — in a well-integrated mix of political and military history. In his book, the author aims to debunk the myths established by the Irish Republicans that still surround the history of the Black and Tans: for example, the notion that they were all ex- criminals and “down-and-outs.” Leeson takes a less conventional approach to the subject by arguing that it was “not character but circumstance” that caused the Black and Tans as well as the Auxiliary Division to take the law into their own hands (69). -

ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context

Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Darwin, Gregory R. 2019. Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42029623 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context A dissertation presented by Gregory Dar!in to The Department of Celti# Literatures and Languages in partial fulfillment of the re%$irements for the degree of octor of Philosophy in the subje#t of Celti# Languages and Literatures (arvard University Cambridge+ Massa#husetts April 2019 / 2019 Gregory Darwin All rights reserved iii issertation Advisor: Professor Joseph Falaky Nagy Gregory Dar!in Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context4 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the migratory supernatural legend ML 4080 “The Mermaid Legend” The story is first attested at the end of the eighteenth century+ and hundreds of versions of the legend have been colle#ted throughout the nineteenth and t!entieth centuries in Ireland, S#otland, the Isle of Man, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, S!eden, and Denmark. -

A History of the O'shea Clan (July 2012)

A History of the O’Shea Clan (July 2012) At the beginning of the second millennium in the High Kingship of Brian Boru, there were three distinct races or petty kingdoms in what is now the County of Kerry. In the north along the Shannon estuary lived the most ancient of these known as the Ciarraige, reputed to be descendants of the Picts, who may have preceded the first Celts to settle in Ireland. On either side of Dingle Bay and inland eastwards lived the Corcu Duibne1 descended from possibly the first wave of Celtic immigration called the Fir Bolg and also referred to as Iverni or Erainn. Legend has it that these Fir Bolg, as we will see possibly the ancestors of the O’Shea clan, landed in Cork. Reputedly small, dark and boorish they settled in Cork and Kerry and were the authors of the great Red Branch group of sagas and the builders of great stone fortresses around the seacoasts of Kerry. Finally around Killarney and south of it lived the Eoganacht Locha Lein, descendants of a later Celtic visitation called Goidels or Gaels. Present Kerry boundary (3) (2) (1) The territories of the people of the Corcu Duibne with subsequent sept strongholds; (1) O’Sheas (2) O’Falveys (3) O’Connells The Eoganacht Locha Lein were associated with the powerful Eoganacht race, originally based around Cashel in Tipperary. By both military prowess and political skill they had become dominant for a long period in the South of Ireland, exacting tributes from lesser kingdoms such as the Corcu Duibne.