King Peak—Yukon Expedition, 1952

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CC O'harra Collection, Glass Lantern Slides and Glass Plate Negatives

SDSM&T Archives: C.C. O’Harra Collection, Glass Lantern Slides and Glass Plate Negatives SDSM&T Archives Devereaux Library South Dakota School of Mines & Technology Rapid City, SD 5/25/2016 SDSM&T Archives: C.C. O’Harra Collection, Glass Lantern Slides and Glass Plate Negatives page 1 Title C.C. O’Harra Collection: Glass Lantern Slides and Glass Plate Negatives Extent 1509 items: 1227 glass lantern slides, 282 glass plate negatives; 1358 unique images Scope and Content The C.C. O’Harra Collection consists of papers, publications, photographs, maps, and files of South Dakota School of Mines president and professor Cleophus Cisney O’Harra. The Devereaux Library’s glass lantern, sometimes referred to as magic lantern, collection consists of over 1200—3 ¼“ x 4” numbered slides and vary in subject matter from geology to meteorology to campus history and include photographs, drawings and maps of international, regional and historical interest. The glass plate negatives consist of 282 plates. The plates are of two size formats—4” x 5” and 5” x 7”, and have an unprotected photo emulsion on the back side. The purpose of the items was primarily instructional. They were produced either from a stationary camera, as shown in the photo or “on site” from a more portable unit. Glass plates were the first step in the reproduction process and, as is evidenced by the notations in the margins of many of the originals, were later submitted to a commercial photo processor to be made into glass slides Provenance The glass lantern slides and glass plate negatives have been a part of the university‘s holdings for several decades. -

P1616 Text-Only PDF File

A Geologic Guide to Wrangell–Saint Elias National Park and Preserve, Alaska A Tectonic Collage of Northbound Terranes By Gary R. Winkler1 With contributions by Edward M. MacKevett, Jr.,2 George Plafker,3 Donald H. Richter,4 Danny S. Rosenkrans,5 and Henry R. Schmoll1 Introduction region—his explorations of Malaspina Glacier and Mt. St. Elias—characterized the vast mountains and glaciers whose realms he invaded with a sense of astonishment. His descrip Wrangell–Saint Elias National Park and Preserve (fig. tions are filled with superlatives. In the ensuing 100+ years, 6), the largest unit in the U.S. National Park System, earth scientists have learned much more about the geologic encompasses nearly 13.2 million acres of geological won evolution of the parklands, but the possibility of astonishment derments. Furthermore, its geologic makeup is shared with still is with us as we unravel the results of continuing tectonic contiguous Tetlin National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska, Kluane processes along the south-central Alaska continental margin. National Park and Game Sanctuary in the Yukon Territory, the Russell’s superlatives are justified: Wrangell–Saint Elias Alsek-Tatshenshini Provincial Park in British Columbia, the is, indeed, an awesome collage of geologic terranes. Most Cordova district of Chugach National Forest and the Yakutat wonderful has been the continuing discovery that the disparate district of Tongass National Forest, and Glacier Bay National terranes are, like us, invaders of a sort with unique trajectories Park and Preserve at the north end of Alaska’s panhan and timelines marking their northward journeys to arrive in dle—shared landscapes of awesome dimensions and classic today’s parklands. -

Catalogue 48: June 2013

Top of the World Books Catalogue 48: June 2013 Mountaineering Fiction. The story of the struggles of a Swiss guide in the French Alps. Neate X134. Pete Schoening Collection – Part 1 Habeler, Peter. The Lonely Victory: Mount Everest ‘78. 1979 Simon & We are most pleased to offer a number of items from the collection of American Schuster, NY, 1st, 8vo, pp.224, 23 color & 50 bw photos, map, white/blue mountaineer Pete Schoening (1927-2004). Pete is best remembered in boards; bookplate Ex Libris Pete Schoening & his name in pencil, dj w/ edge mountaineering circles for performing ‘The Belay’ during the dramatic descent wear, vg-, cloth vg+. #9709, $25.- of K2 by the Third American Karakoram Expedition in 1953. Pete’s heroics The first oxygenless ascent of Everest in 1978 with Messner. This is the US saved six men. However, Pete had many other mountain adventures, before and edition of ‘Everest: Impossible Victory’. Neate H01, SB H01, Yak H06. after K2, including: numerous climbs with Fred Beckey (1948-49), Mount Herrligkoffer, Karl. Nanga Parbat: The Killer Mountain. 1954 Knopf, NY, Saugstad (1st ascent, 1951), Mount Augusta (1st ascent) and King Peak (2nd & 1st, 8vo, pp.xx, 263, viii, 56 bw photos, 6 maps, appendices, blue cloth; book- 3rd ascents, 1952), Gasherburm I/Hidden Peak (1st ascent, 1958), McKinley plate Ex Libris Pete Schoening, dj spine faded, edge wear, vg, cloth bookplate, (1960), Mount Vinson (1st ascent, 1966), Pamirs (1974), Aconcagua (1995), vg. #9744, $35.- Kilimanjaro (1995), Everest (1996), not to mention countless climbs in the Summarizes the early attempts on Nanga Parbat from Mummery in 1895 and Pacific Northwest. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC)

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Summits on the Air USA - Colorado (WØC) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S46.1 Issue number 3.2 Date of issue 15-June-2021 Participation start date 01-May-2010 Authorised Date: 15-June-2021 obo SOTA Management Team Association Manager Matt Schnizer KØMOS Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Page 1 of 11 Document S46.1 V3.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Change Control Date Version Details 01-May-10 1.0 First formal issue of this document 01-Aug-11 2.0 Updated Version including all qualified CO Peaks, North Dakota, and South Dakota Peaks 01-Dec-11 2.1 Corrections to document for consistency between sections. 31-Mar-14 2.2 Convert WØ to WØC for Colorado only Association. Remove South Dakota and North Dakota Regions. Minor grammatical changes. Clarification of SOTA Rule 3.7.3 “Final Access”. Matt Schnizer K0MOS becomes the new W0C Association Manager. 04/30/16 2.3 Updated Disclaimer Updated 2.0 Program Derivation: Changed prominence from 500 ft to 150m (492 ft) Updated 3.0 General information: Added valid FCC license Corrected conversion factor (ft to m) and recalculated all summits 1-Apr-2017 3.0 Acquired new Summit List from ListsofJohn.com: 64 new summits (37 for P500 ft to P150 m change and 27 new) and 3 deletes due to prom corrections. -

1953 the Mountaineers, Inc

fllie M®��1f�l]�r;r;m Published by Seattle, Washington..., 'December15, 1953 THE MOUNTAINEERS, INC. ITS OBJECT To explore and study the mountains, forests, and water cours es of the Northwest; to gather into permanent form the history and traditions of this region; to preserve by encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise, the natural beauty of North west America; to make expeditions into these regions in ful fillment of the above purposes ; to encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all lovers of out-door life. THE MOUNTAINEER LIBRARY The Club's library is one of the largest mountaineering col lections in the country. Books, periodicals, and pamphlets from many parts of the world are assembled for the interested reader. Mountaineering and skiing make up the largest part of the col lection, but travel, photography, nature study, and other allied subjects are well represented. After the period 1915 to 1926 in which The Mountaineers received books from the Bureau of Associate Mountaineering Clubs of North America, the Board of Trustees has continuously appropriated money for the main tenance and expansion of the library. The map collection is a valued source of information not only for planning trips and climbs, but for studying problems in other areas. NOTICE TO AUTHORS AND COMMUNICATORS Manuscripts offered for publication should be accurately typed on one side only of good, white, bond paper 81f2xll inches in size. Drawings or photographs that are intended for use as illustrations should be kept separate from the manuscript, not inserted in it, but should be transmitted at the same time. -

The Great White Mountains of the St Elias

PAUL KNOTT The Great White Mountains of the St Elias he St Elias range is a vast icy wilderness straddling the Alaska-Yukon T border and extending more than 200km in each direction. Its best known mountains are St Elias and Logan, whose scale is among the largest anywhere in terms of height and bulk above the surrounding glacier. Other than the two standard routes on Mount Logan, the range is still travelled very little in spite of ready access by ski plane. This may be because the scale, combined with challenging snow conditions and prolonged storms, make it a serious place to visit. Typically, the summits are buttressed by soaring ridges and guarded by complex broken glaciers and serac-torn faces. Climbing here is a distinctive adventure that has attracted a dedicated few to make repeated exploratory trips. I hope to provide some insight into this adventure by reflecting on the four visits I have enjoyed so far to the range. In 1993 Ade Miller and I were inspired by pictures of Mount Augusta (4288m), which not only looked stunning but also had obvious unclimbed ridges. Arriving in Yakutat (permanent population 600) we were struck by the enthusiasm and friendliness of our glacier pilot, Kurt Gloyer. There were few other climbers and we prepared our equipment amongst bits of plane in the hangar. Landing on the huge Seward glacier, we stepped out of the plane into knee-deep snow. It took some digging to find a firm base for the tents. Our first attempt to move anywhere was thwarted when Ade fell into an unseen crevasse 150m from the tents. -

Inmemoriam1994 316-334.Pdf

In Memoriam TERRIS MOORE 1908-1993 Terris Moore, age 85, of Cambridge, Massachusetts, explorer, mountaineer, light-plane pilot and President Emeritus of the University of Alaska, died on November 7 after a massive heart attack. He became internationally known in 1932 when he and three companions reached and surveyed Minya Konka (now called Gongga Shan) in Sichuan, China. Moore and Richard Burdsall, both AAC members, ascended this very difficult mountain (that Burdsall and Arthur Emmons surveyed as 24,490 feet high), and in doing so climbed several thousand feet higher than Americans had gone before. At the time, Moore was the outstanding American climber. Moore, Terry to his friends, was born in Haddonfield, New Jersey, on April 11, 1908 and attended schools in Haddonfield, Philadelphia and New York before entering and graduating from Williams College, where he captained the cross-country team and became an avid skier. After graduating from college, he attended the Harvard School of Business Administration, from which he received two degrees: Master of Business Administration and Doctor of Commercial Science. Terry’s mountain climbing had begun long before this time. In 1927, he climbed Chimborazo (20,702 feet) in Ecuador and made the first ascent of 17,159-foot Sangai, an active volcano there. Three years later, he joined the Harvard Mountaineering Club and also became a member of the American Alpine Club, connections which led that year to his making the first ascent of 16,400-foot Mount Bona in Alaska with Allen Carp& and the first unguided ascent of Mount Robson in the Canadian Rockies. -

The Future of Alaska

RESOURCES FOR THE FUTURE LIBRARY COLLECTION RESOURCES FOR THE FUTURE LIBRARY COLLECTION POLICY AND GOVERNANCE POLICY AND GOVERNANCE Economic Consequences of Statehood The Future of Alaska The Future of Alaska Economic Consequences of Statehood George W. Rogers Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 21:18 09 May 2016 )3". RFF Press strives to minimize its impact on the environment George W. Rogers Content Type: Black & White Paper Type: White Page Count: 346 File type: Internal Policy and Governance Vol 10.qxd 9/17/2010 2:29 PM Page i RESOURCES FOR THE FUTURE LIBRARY COLLECTION POLICY AND GOVERNANCE Volume 10 The Future of Alaska Economic Consequences of Statehood Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 21:18 09 May 2016 Policy and Governance Vol 10.qxd 9/17/2010 2:29 PM Page ii Full list of titles in the set POLICY AND GOVERNANCE Volume 1: NEPA in the Courts Volume 2: Representative Government and Environmental Management Volume 3: The Governance of Common Property Resources Volume 4: A Policy Approach to Political Representation Volume 5: Science & Resources Volume 6: Air Pollution and Human Health Volume 7: The Invisible Resource Volume 8: Rules in the Making Volume 9: Regional Conflict and National Policy Volume 10: The Future of Alaska Volume 11: Collective Decision Making Volume 12: Steel Production Volume 13: Enforcing Pollution Control Laws Volume 14: Compliance & Public Authority Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 21:18 09 May 2016 The Future of Alaska Economic Consequences of Statehood George W. Rogers Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 21:18 09 May 2016 ~RFFPRESS - RESOURCES FOR THE FUTURE New York • London First published in 1962 by The johns Hopkins University Press for Resources for the Future This edition first published in 2011 by RFF Press, an imprint of Earthscan First edition ©The johns Hopkins University Press 1962 This edition © Earthscan 1962, 2011 All rights reserved. -

Wrangell-St. Elias Alaska

Wrangell - St. Elias National Park Service National Park and National Preserve U.S. Department of the Interior Wrangell-St. Elias Alaska The wildness of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation vest harbor seals, which feed on fish and In late summer, black and brown bears, drawn and Preserve is uncompromising, its geography Act (ANILCA) of 1980 allows the subsistence marine invertebrates. These species and many by ripening soapberries, frequent the forests awe-inspiring. Mount Wrangell, namesake of harvest of wildlife within the park, and preserve more are key foods in the subsistence diet of and gravel bars. Human history here is ancient one of the park's four mountain ranges, is an and sport hunting only in the preserve. Hunters the Ahtna and Upper Tanana Athabaskans, and relatively sparse, and has left a light imprint active volcano. Hundreds of glaciers and ice find Dall's sheep, the park's most numerous Eyak, and Tlingit peoples. Local, non-Native on the immense landscape. Even where people fields form in the high peaks, then melt into riv large mammal, on mountain slopes where they people also share in the bounty. continue to hunt, fish, and trap, most animal, ers and streams that drain to the Gulf of Alaska browse sedges, grasses, and forbs. Sockeye, Chi fish, and plant populations are healthy and self and the Bering Sea. Ice is a bridge that connects nook, and Coho salmon spawn in area lakes and Long, dark winters and brief, lush summers lend regulati ng. For the species who call Wrangell the park's geographically isolated areas. -

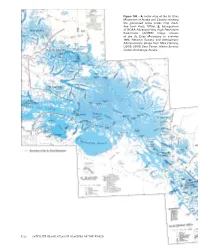

A, Index Map of the St. Elias Mountains of Alaska and Canada Showing the Glacierized Areas (Index Map Modi- Fied from Field, 1975A)

Figure 100.—A, Index map of the St. Elias Mountains of Alaska and Canada showing the glacierized areas (index map modi- fied from Field, 1975a). B, Enlargement of NOAA Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) image mosaic of the St. Elias Mountains in summer 1995. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration image from Mike Fleming, USGS, EROS Data Center, Alaska Science Center, Anchorage, Alaska. K122 SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD St. Elias Mountains Introduction Much of the St. Elias Mountains, a 750×180-km mountain system, strad- dles the Alaskan-Canadian border, paralleling the coastline of the northern Gulf of Alaska; about two-thirds of the mountain system is located within Alaska (figs. 1, 100). In both Alaska and Canada, this complex system of mountain ranges along their common border is sometimes referred to as the Icefield Ranges. In Canada, the Icefield Ranges extend from the Province of British Columbia into the Yukon Territory. The Alaskan St. Elias Mountains extend northwest from Lynn Canal, Chilkat Inlet, and Chilkat River on the east; to Cross Sound and Icy Strait on the southeast; to the divide between Waxell Ridge and Barkley Ridge and the western end of the Robinson Moun- tains on the southwest; to Juniper Island, the central Bagley Icefield, the eastern wall of the valley of Tana Glacier, and Tana River on the west; and to Chitistone River and White River on the north and northwest. The boundar- ies presented here are different from Orth’s (1967) description. Several of Orth’s descriptions of the limits of adjacent features and the descriptions of the St. -

Gazetteer of Yukon

Gazetteer of Yukon Updated: May 1, 2021 Yukon Geographical Names Program Tourism and Culture Yukon Geographical Place Names Program The Yukon Geographical Place Names Program manages naming and renaming of Yukon places and geographical features. This includes lakes, rivers, creeks and mountains. Anyone can submit place names that reflect our diverse cultures, history and landscape. Yukon Geographical Place Names Board The Yukon Geographical Place Names Board (YGPNB) approves the applications and recommends decisions to the Minister of Tourism and Culture. The YGPNB meets at least twice a year to decide upon proposed names. The Board has six members appointed by the Minister of Tourism and Culture, three of whom are nominated by the Council of Yukon First Nations. Yukon Geographical Place Names Database The Heritage Resources Unit maintains and updates the Yukon Geographical Place Names Database of over 6,000 records. The Unit administers the program for naming and changing the names of Yukon place names and geographical features such as lakes, rivers, creek and mountains, approved by the Minister of Tourism and Culture, based on recommendations of the YGPNB. Guiding Principles The YGPNB bases its decisions on whether to recommend or rescind a particular place name to the Minister of Tourism and Culture on a number of principles and procedures first established by the Geographic Names Board of Canada. First priority shall be given to names with When proposing names for previously long-standing local usage by the general unnamed features—those for which no public, particularly indigenous names in local names exist—preference shall be the local First Nation language. -

GLACIERS of ALASKA by BRUCE F

Glaciers of North America— GLACIERS OF ALASKA By BRUCE F. MOLNIA With sections on COLUMBIA AND HUBBARD TIDEWATER GLACIERS By ROBERT M. KRIMMEL THE 1986 AND 2002 TEMPORARY CLOSURES OF RUSSELL FIORD BY THE HUBBARD GLACIER By BRUCE F. MOLNIA, DENNIS C. TRABANT, ROD S. MARCH, and ROBERT M. KRIMMEL GEOSPATIAL INVENTORY AND ANALYSIS OF GLACIERS: A CASE STUDY FOR THE EASTERN ALASKA RANGE By WILLIAM F. MANLEY SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF THE GLACIERS OF THE WORLD Edited by RICHARD S. WILLIAMS, Jr., and JANE G. FERRIGNO U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1386–K About 5 percent (about 75,000 km2) of Alaska is presently glacierized, including 11 mountain ranges, 1 large island, an island chain, and 1 archipelago. The total number of glaciers in Alaska is estimated at >100,000, including many active and former tidewater glaciers. Glaciers in every mountain range and island group are experiencing significant retreat, thinning, and (or) stagnation, especially those at lower elevations, a process that began by the middle of the 19th century. In southeastern Alaska and western Canada, 205 glaciers have a history of surging; in the same region, at least 53 present and 7 former large ice-dammed lakes have produced jökulhlaups (glacier-outburst floods). Ice-capped Alaska volcanoes also have the potential for jökulhlaups caused by subglacier volcanic and geothermal activity. Satellite remote sensing provides the only practical means of monitoring regional changes in glaciers in response to short- and long-term changes in the maritime and continental climates of Alaska. Geospatial analysis is used to define selected glaciological parameters in the eastern part of the Alaska Range.